After a relaxing day off and some turnover in personnel, we’re ready to start week two of fish blitz.

Sunday was our off day to recuperate and off-gas (allow any residual nitrogen to exit our bloodstream). After bringing leavers to the ferry and enjoying huevos rancheros at JJ’s Texas Coast Café, we wandered around town and browsed the shops. Later, Rob took NOAA research associate Lee Richter and me on a scenic tour of the island to check out the beautiful beach lookouts, followed by pickup beach volleyball with the locals in Cinnamon Bay. It was a great scene—despite the high level of play everyone was friendly and welcoming, and we would cool off and de-sand in the clear, refreshing water between matches, striking up conversations with fellow waders.

On Monday, the surveys proceeded as usual, although this week Mike moved me around to different boats, so I had a chance to chat up different people and learn the quirks in operating culture and inside jokes of each boat. I’m feeling good about fish identification, so Mike briefed me on an alternate fish count method, Reef Visual Census (RVC). Rather than moving forward along a transect line, the diver stays at a fixed point, noting the species and number of all fish in a 7.5m radius cylinder stretching the height of the water column. The species and number of all fish are recorded for five minutes, and then only new species that enter the cylinder between five and ten minutes are recorded, and then only new species between ten and fifteen minutes. At the end of the survey, the diver writes down the average size of each species, as well as a minimum and maximum. The fish blitz group has been using RVC surveys as a means of calibrating fish counts, and they’re comparing the two methods for efficacy and accuracy. So far it appears that divers counting along a transect can better see and identify small fish, while RVC divers tend to catch more of the larger fish.

I’ve felt much more engaged with the dives with an actual data sheet in hand. On my first survey, I busily scribbled down all of the species flitting around directly below me for a full 30 seconds before I remembered to look up and around me. My already questionable underwater handwriting soon deteriorated into a frantic scrawl as I realized just how much bigger 7.5 meters is than 4. On the surface I compared notes with the official fish diver to see if we were getting similar species and sizes. Everything looks bigger underwater, so I learned to be careful not to exaggerate fish size.

In all of my previous diving experience, I’ve been moving constantly to explore a reef or follow a transect, so it was a new experience to stay completely still for fifteen minutes. I would wait a while to begin my survey as I recorded information about the site, date, time, and conditions, and fish that retreated upon my arrival would reemerge, and some curious individuals would approach or swim by several times. A few minutes into most surveys I would find a red hind peering at me from behind a soft coral, observing me for duration of the count. I did find that I was more attuned to larger fish passing by and the schools of silvery fish that flashed overhead than I had been with previous transect experience, while smaller fish near the periphery of my cylinder were more likely to escape me.

We had more weather related excitement this week: Wednesday brought winds and rain that developed into thunderstorms by midday. The seas were rough and we had a few sites with ripping current, requiring substantial effort to stay on the transect. As we came up from the second dive I was mesmerized by the sight and sound of raindrops from below surface of the water, something I’d never experienced before. Storms dramatically wreathed the slopes of nearby Tortola, and as lightning forks drew closer we tucked into a protected bay to wait out the storm. For the rest of the day we dodged intermittent squalls, being careful to avoid diving near lightning. The reefs are muted and peaceful in the rain, and I was reluctant to leave the warm water for winds and waves on the surface.

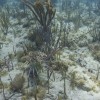

There have been a few other breaks in routine, especially with all the boat shuffling. On my last day on Stenopus Rob brought us to a shallow, clear site in No Name Bay for a brief dive/snorkel to check out a patch of Acropora prolifera, a hybrid of endangered corals A. palmata and A. cervicornis. Margaret, an Acropora expert, was particularly delighted to see the unusually branching colonies. On board the boat Acropora, we made an excursion to St. Thomas to refill nitrox tanks (nitrox is an oxygen-enhanced mix that allows longer dives at depth), so I had a brief chance to explore Red Hook harbor.

After two weeks I’ve become well versed in St. John’s restaurant scene. We went into town for dinner almost every night, with the exception of a group pizza night or two and the evening when SFCN I&M Coordinator Matt Patterson cooked us a spectacular pasta dinner. Many members of the team have been to St. John several times for fish blitz and Rob lived and worked here for years, so they know all the best spots, from delicious barbecue at the Barefoot Cowboy Lounge to Rhumb Lines pad thai and key lime pie for NOAA scientist Susie Holst’s birthday celebration. Often, coral talk would continue over dinner, with rapid-fire exchange of Latin names and proud comparisons of who had found the most Diadema.

The mission ended with a celebratory dinner for the whole on St. Thomas. We were all exhausted and a bit bruised and battered after two weeks of intensive diving and rough boat rides, but we happy with the work we had done—the teams covered about 285 sites on both islands, collecting important data for population monitoring and habitat mapping. The best part of the trip was seeing people from different agencies, groups that may compete for funding and have slightly different customs and procedures, coming together and working side by side. As Mark Monaco, the director of NOAA’s Center for Costal Monitoring and Assessment program put it, “At the end of the day, we’re all on the same team. We’re just trying to get it right.”

Thanks so much to Mike for coordinating my experience here and a holla to Rob for being a great island guide. Thanks also to everyone for working with me, driving me, feeding me, hanging out with me, and imparting wonderful advice! It was wonderful to meet you all.