You might be surprised to learn that Mt. Everest is not the tallest mountain in the world; that honor would be reserved for Mauna Kea, HI. While Mt. Everest has the highest altitude at 29,029ft above sea level, if measured from its base on the sea floor, the volcanic summit of Mauna Kea surpasses Mt. Everest at 33,500ft (NOAA). So why this fun fact? Because a second fun fact is that I can technically say I’ve summited the tallest mountain in the world! (Shsh, please let me have this one.)

While it might have been wiser for me to spend my first day off in a while resting, sleeping, or catching up on my expense reporting, the lure of an extremely strenuous all-day hike was too much to resist. After some careful research about the hike specs (hence stumbling across the fun fact), I wake up at 4:30 AM to get to the trailhead at sunrise. Most people take 8-12 hours to climb up the 4,000 ft in elevation and back, and I also want to give myself an hour to acclimate to the altitude at the visitor’s center, which sits at 9,000 ft above sea level. During this time, I chug lots of water, fill out my hiking permit, and read the multitude of signs warning about symptoms of altitude sickness. I’ve spent the last few months at sea level, am slightly out of hiking shape, and am not ready to be dragged out by park rangers so my plan is to go as slow as possible.

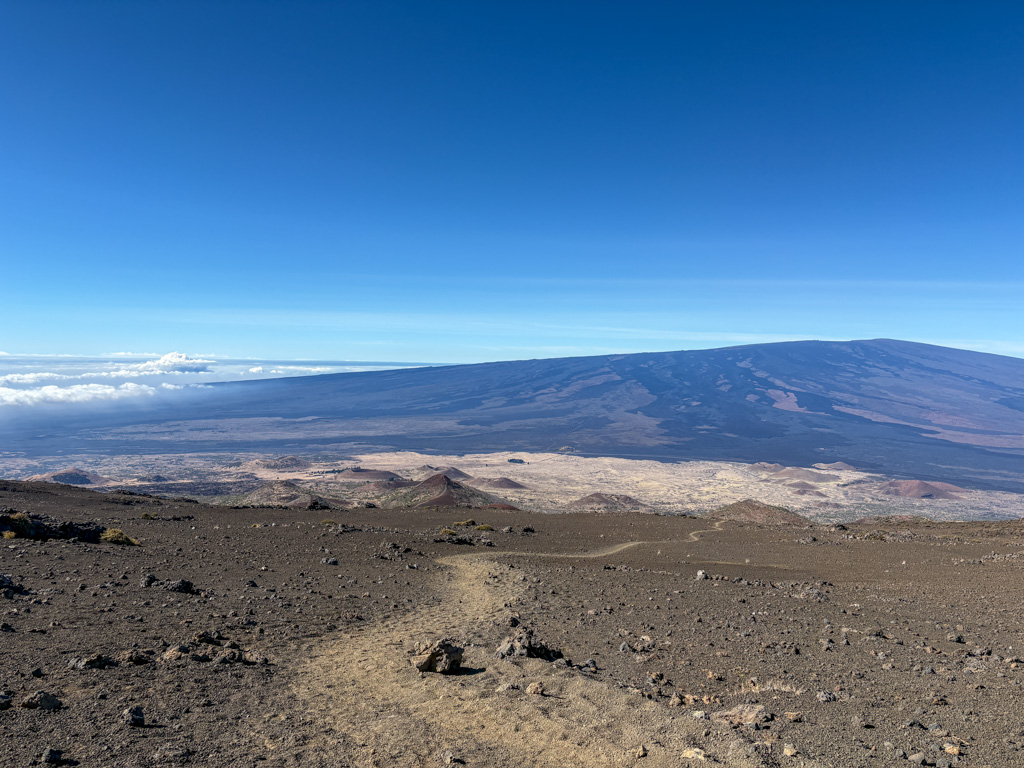

With enough self-control to surprise my mom, I slowly make my ascent up the dusty volcanic landscape. The trail quickly turns from some sparse shrubs to fields of crumbled rock, and I become absurdly happy when I spy a ladybug, the only critter I’ve laid eyes on for hours. I hike so slow that I walk in my own cloud of dust, which seems especially pathetic as I’m passed by two groups on their way up. However, by mile 4, my self-pity turns into slightly righteous pride as the groups pass back by me on their way down, having turned around before the summit after getting hit by nausea and dizziness. It would seem my self-control pays off, and I make it the 6 miles to the top without any symptoms.

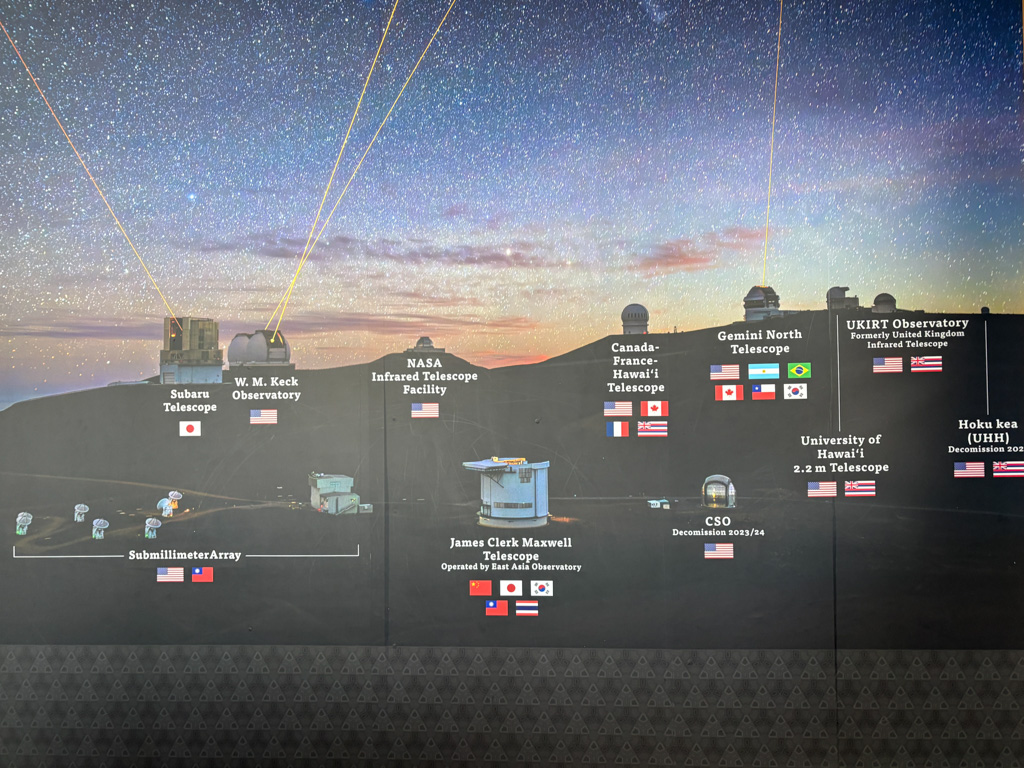

I don’t hike to the true summit out of Manau Kea, as it is considered a sacred place of significant cultural and religious importance to native Hawaiians, but the view at the end of the trail is spectacular. The massive telescopes from NASA, Subaru, and various countries are out of place but also fitting as some kind of settlement on Mars. After finishing my family-size bag of jerky, I head back down and make it safely back to the parking lot, saved from an embarrassing ranger rescue. However, I am not entirely spared from embarrassment as I can barely walk into the office the next morning, ready to meet the team at Kaloko-Honokōhau.

Kaloko-Honokōhau is a park located on the Big Island with a unique history and an array of ecosystems. It boasts over 200 anchialine pools and was founded only because of the community effort, hard work, and foresight of native Hawaiians seeking to preserve the history and natural resources of this ancient settlement. The park boundaries also encompass parts of multiple ahupua‘a designations, which are traditional geographical boundaries that encompass a “slice” of the islands, from the sea to mountains. The NPS team at Kaloko-Honokōhau is very informed and dedicated to the land and ocean’s past history and present significance, sharing their knowledge with me so I can be a respectful visitor.

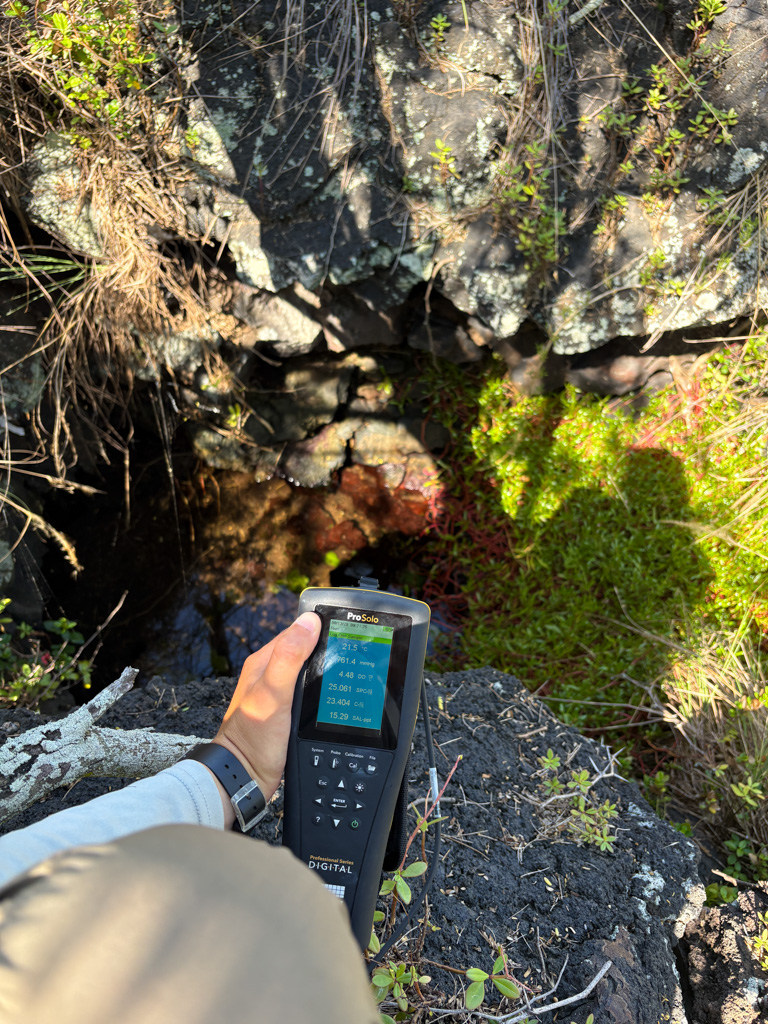

I head out with Kaile’a Annandale, Rachel Nunley and Katie Cartee for anchialine pool assessments after Rachel strongarms GIS for our survey. It puts up quite a fight, but she emerges impressively victorious, and we set out for the field. The pools are beautiful to witness and have a very interesting backstory. They are filled with brackish water, but above ground sources like streams or incoming waves. Instead, fresh water mixes with seawater in the deep, porous lava rocks and seeps up into the pools, with the depths changing depending on tides. Species like the ʻōpaeʻula, or Hawaiian Red Shrimp, also hang out in this hidden underground world and can be found in the pools during high tides. Upon first seeing these adorable little guys, I think I squeal loud enough for visitors to hear me across the lava fields.

The team explains to me how rising sea levels are predicted to drastically change pools. Places that are too dry for pools to be present now might soon turn into more permanent anchialine systems, possibly expanding where the ʻōpaeʻula can live. Some pools that used to be independent of each other might soon become connected with higher tides, as well as connected to fishponds and the ocean. This can greatly impact the ecology of each pool as native and non-native/invasive species are able to move more freely between pools. A big concern with all this change is the introduction of invasive fish that eat the shrimp, as they can move from the previously unconnected fishpond and ocean.

The next day, to access the achialine pools at the north end of the park, we get to walk over the loko kuapā, or fish pond wall. Originally constructed hundreds of years ago, this fishpond is the largest in Hawai’i and was used by royalty. The wall is dry-stacked, an impressive crafting feat. Each rock has been perfectly chosen and placed within the wall so that no mortar or type of binding agent is needed. This astounding craftsmanship holds up to the pounding of surf and even has two ‘auwai kai, or channels, with mākāhā, or gates, on both ends to manage the movement of fish between the ocean and pond (NPS).

Later, Kaile’a receives a call that a monk seal has been reported on the park beach. Unlike the beaches of Kalaupapa, where monk seals can lounge without disruption from the public, Kaloko-Honokōhau has a lot of curious visitors who often can get too close, even by accident, as the seals are really good at looking like rocks. While we wait for a volunteer organization to show up to babysit, Kaile’a gets another call – apparently, another monk seal has been spotted at the opposite end of the beach! This is an extremely rare occurrence as there are only 10 seals that hang out on the Big Island, and to have both on the beach during one day is unusual. While Morgan Chambers keeps a watchful eye over the female at the north end, Kaile’a and I “babysit” at the south end.

We ID our seal by the tag on her flipper as a one year old female, and Kaile’a explains that she is smart and often found in the harbor next door looking for fish scraps. Unfortunately, being smart hasn’t been in her best interest, and there is worry she might be injured or killed in retaliation by fishermen who find her a nuisance. For now, she blinks at us innocently between her naps next to a sea turtle.

The week flies by too fast, and soon, it’s my last day. After a lot of time in the blazing heat of the lava rocks, we get a nice little cool off with some snorkeling around the shore, checking for coral bleaching and removing any debris we find. People might be getting tired of me saying how amazing things are that I’ve never experienced before… but it keeps happening! Kaloko-Honokōhau has the most coral cover I’ve ever seen, with beautiful submerged arches to swim through and even microorganisms that flash different colors in broad daylight!

I try and fail not to yell loudly through my snorkel as I watch tiny little organisms float by, flashing neon blue, then orange, then green. I can only imagine how magnificent they are in the dark. I have a wonderful time diving down under the arches and playing chicken with eels hiding in the abundant coral. If you were wondering, I am definitely the chicken. While not as fishy as Kalaupapa, Kaloko-Honokōhau’s coral is something else.

I only found an abandoned snorkel and some fishing line after an hour, so it seems Kaloko-Honokōhau is in pretty good shape. Kaile’a says there is no alarming bleaching either, and these little victories make for a great day. I end my time with the Kaloko-Honokōhau NPS team at a wonderful bicultural talk by Kekuʻiapōiula Keliipuleole on anchialine pools. After only a week, I’m well on my way to becoming shrimp-tern level of obsessed. I am so sad to say goodbye to this amazing and dedicated team and am grateful for the fun times and field snacks I shared with them.

I spend my last two days in Kona on some dives with Sarah Milisen, my super awesome host and a divemaster in the area. She takes me on a shore dive to look for tiger sharks, annndddd we have the luckiest dive ever. We see a tiger within the first 10 minutes, and almost simultaneously, a pod of spinner dolphins glides by! I may not be one for dancing in clubs, but you will definitely find me busting a move at 70ft if I see a shark. This was my first tiger and the most incredible experience. She drifted on the edge of our peripheral for a while, where the spectacular visibility turned into smokier water, and then went on her way. Our luck didn’t stop there: we saw an octopus, giant trevally, finescale triggerfish, gold lace nudibranch, and two bait balls that collided together in a spectacular display right in front of us.

The next day, I join Sarah for an Ocean Defender’s Alliance marine debris clean up she is managing at Mahukona Beach Park. ODA has a super impressive volunteer presence with more than 50 SCUBA divers, free divers, snorkelers, and topside supporters. Groups split up to tackle different locations and debris types like a well-oiled machine, and I have a great dive looking for fishing line, and of course, admiring the coral. I only come across two lead weights and a few pieces of line, which is pretty awesome. Other teams hit some tire jackpots that they removed with lift bags. I can’t thank Sarah enough (and her precious pup, Alani) for including me in these awesome opportunities and welcoming me into her home for the week. Thank you for everything Sarah!