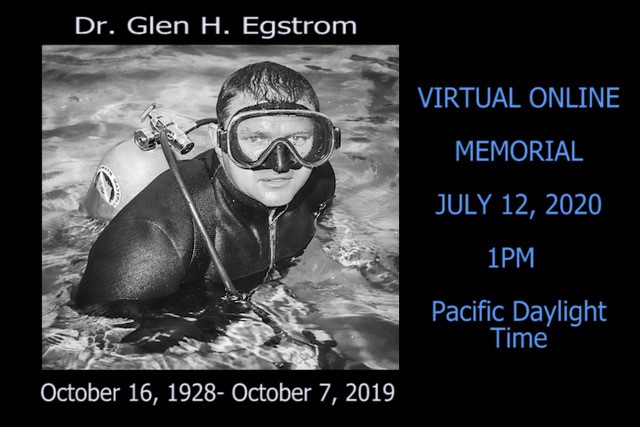

Glen H. Egstrom, Ph.D.

Founding Director, Past Chairman of the Board, and Director Emeritus

October 16, 1928 – October 7, 2019

“A Life Well Lived”

October 16, 1928 dawned as just another day in America. Just a week earlier, the New York Yankees had swept the St. Louis Cardinals 4-0 to win the World Series. American troops had been home from the trenches and battlefields of World War I for about ten years. Calvin Coolidge was the President of the United States, and though Americans had no clue what was about to befall them, the start of the Great Depression was just one year away.

However, this date was going to be very memorable for any number of folks who lived in Jamestown, North Dakota, a little town perched at the confluence of the James and Pipestem Rivers–population 8,000. Jamestown was founded in 1872 to support a major Northern Pacific Railway repair yard near its James River rail crossing. Known as the “Pride of the Prairie,” Jamestown is home to the National Buffalo Museum.

This date started unremarkably for electrician Milford Egstrom and his wife, Emily, who managed the Jamestown Bus Terminal and provided 24/7 taxi dispatching for the town; but by the end of the day, their lives would be changed forever with the arrival of their first child, Glen Howard Ole Axel Egstrom. The extra middle names, Ole and Axel, were airplane pilots and best friends of Milford but were quickly jettisoned by Glen in young adulthood! The entire family was delighted with Glen’s arrival, and his eight-year-old aunt, Norma Deloris Egstrom, was especially pleased. Within 15 years, Glen and his family would have cause to be very proud of his “Aunt Norma” who grew up to become the famous singer and actress, the inimitable Miss Peggy Lee!

Glen grew up hunting and fishing the lands and waterways surrounding Jamestown, especially the James River and its associated James Reservoir, a 12 mile stretch of three interlocking lakes that had been formed by the Jamestown Dam. Glen became a standout high school athlete in football, basketball, and baseball, garnering all-state honors. Glen, an accomplished swimmer, also became a very popular local lifeguard.

After high school, Glen headed for the University of North Dakota (UND) intending to play collegiate football. During his freshman year, he severely damaged a knee. The university brought a renowned orthopedic surgeon from the Minneapolis Lakers into North Dakota to repair Glen’s knee, but he never played football again and turned his attention to becoming a serious basketball athlete. In the Spring of his sophomore year, Glen was taking a physical education class and was paired in a game of badminton with Donna Wehmhoefer. They soon started dating and were married shortly after their college graduation in 1950.

The newly married Egstroms headed to Tracy, California, where they both had obtained teaching positions in the local middle school. They started their new jobs at the end of the Summer in 1950 just a couple of months after the start of the Korean Conflict. It took only until the Spring of 1951 for the Jamestown draft board to catch up with Glen and draft him into the U. S. Army.

Glen graduated as a Private from boot camp, during which he received Trainee of the Week honors from Major General Robert B. McClure. He was sent immediately to the first Antiaircraft Artillery Officer Candidate School (OCS) and graduated with an officer’s commission and orders to Korea to serve as a platoon leader with the 3rd Infantry Division supervising field artillery. A few months after arriving in Korea, Glen was detailed to the U. S. Air Force 6147th Tactical Air Control Squadron and flew 28 combat missions as a Forward Air Controller in a T-6 aircraft providing close air support, aerial observation, and artillery spotting.

While Glen was in Korea, Donna moved to Los Angeles and took a position as a Los Angeles County social worker. 1LT Glen Egstrom was released from Korea, placed on inactive duty and joined Donna on October 16, 1953 in Los Angeles. Ultimately, he was honorably discharged from the Army Reserve with the rank of Major on July 26, 1965. Glen decompressed from the stresses of war by heading to the Los Angeles beaches every day to surf and play beach volleyball. In January, 1954, he enrolled in a Master’s program at the University of California – Los Angeles (UCLA) and was quickly hired as a teaching assistant (TA). Within a short period of time, Glen became a player/coach on the UCLA Men’s Volleyball Team eligible, because he had not played volleyball at UND. In 1956, armed with $25 of university funding and uniforms he borrowed from the UCLA Bruins Men’s Basketball team, Glen lead his team to Seattle where they won the national collegiate volleyball championship.

Glen completed his Master’s degree at UCLA in 1957 and while he continued to be employed as a TA at UCLA, completed his Ph.D. at the University of Southern California (USC) in 1961 and was subsequently hired as an assistant professor of kinesiology at UCLA.

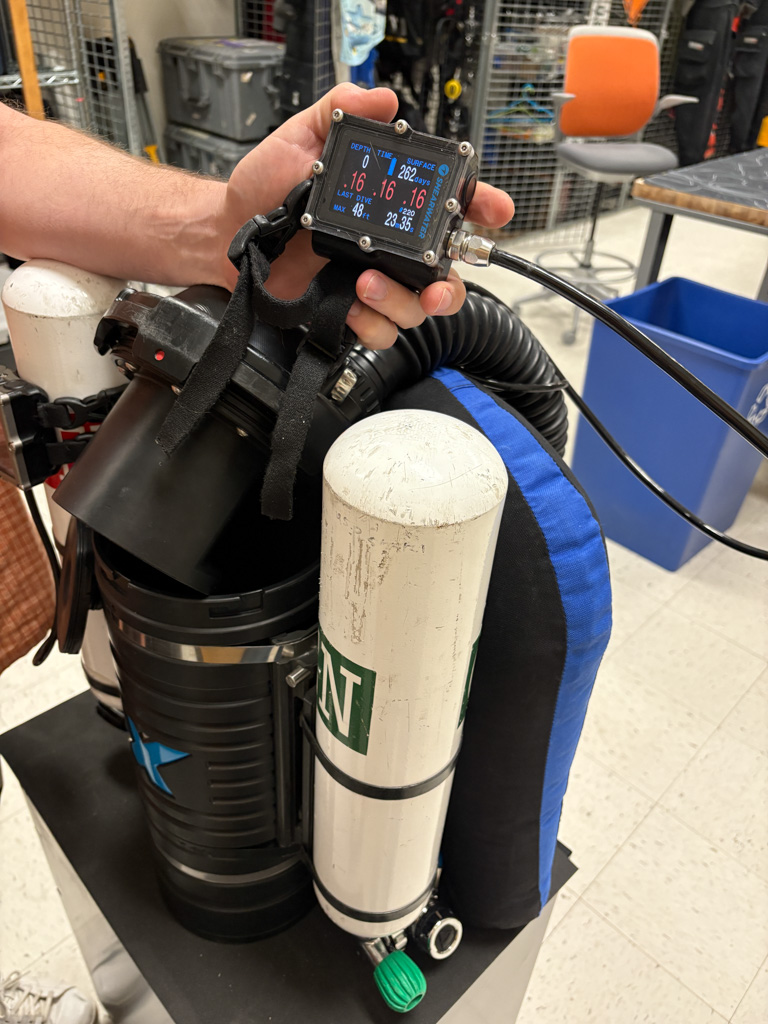

During this time, Glen continued to love any activity related to the water and kept up the ocean swimming and surfing in Southern California while teaching at UCLA. His foray into scuba diving was particularly interesting. Aunt Peggy Lee was married for a brief period to actor Dewey Martin, who obtained some of the first regulators and scuba equipment that Jacques-Yves Cousteau sent into America via René Bussoz of Rene’s Sporting Goods in Westwood, California. These self-contained underwater breathing units he called “Aqua-Lungs.” Dewey’s contract with the movie studio prohibited him from any dangerous activities, including scuba diving, and “Uncle Dewey” gave his double-hose regulator and twin cylinders to Glen in 1957. While all this was happening, Glen and Donna were busy growing their family with the addition of daughter Gail (1954), son Eric known as “Buck” (1957), and daughter Karen (1961). All three were quickly introduced to their parents’ love of the water and two became certified divers. Gail qualified as a scuba instructor, Karen shared Glen’s love of sailing, and Buck became incredibly skilled at surfing and foil surfing.

Glen had become the faculty sponsor for the UCLA Skin and Scuba Club and asked the Los Angeles County Scuba program, considered to be the first scuba training program in the United States, to conduct a basic certification course at UCLA. Once certified as a diver, Glen undertook the arduous Los Angeles County Underwater Instructor Certification Course in 1964 to become a certified instructor and graduated with the Outstanding Candidate Award. He served as its President 1967-1970. In 1964, Glen was appointed the UCLA Diving Officer, a position he held until 1992. Glen was notorious throughout the diving community for his nine-month scuba instructor training course (ITC) at UCLA. One observer of his ITC was quoted as saying, “Egstrom ain’t training scuba instructors; he’s training university diving officers!” His scientific and recreational diver training program at UCLA was highly acclaimed, graduating hundreds of divers and instructors who themselves continue to make considerable contributions as part of Glen’s legacy.

In 1966, Glen became a member, instructor and instructor trainer with the National Association of Underwater Instructors (NAUI) and maintained his membership for life. Glen served as NAUI’s president from 1970-1975 and held a variety of leadership/advisory positions from 1970-1995.

During this period, Glen served as a reserve deputy sheriff with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, their Diving Safety Officer, and an active member of the Sheriff’s Reserve Marine Company 218. Glen retired in 2004 with the rank of Captain.

Over the years, Glen provided exemplary leadership to many other organizations, especially during their formative years. Organizations such as the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (AAUS), American College of Sports Medicine, Council for National Cooperation in Aquatics, Divers Alert Network (DAN) , Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs, Marine Technology Society, National Spa and Pool Institute (NSPI) and the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society (UHMS) all benefitted from Glen’s leadership and counsel. The organization to which he was most committed was the Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society® which he helped found. To this special group, he provided enduring leadership and instilled within it his lifelong commitment to “investing in people.” His natural leadership gifts allowed Glen to create, build, and serve communities that continue to help people safely experience the underwater world.

Glen was the ultimate “people collector,” and anyone invited to his Mar Vista dining table was thrilled to be part of so many loving, thoughtful, and provocative discussions that often lasted late into the evening. Many were additionally thrilled to have been invited to dive with Glen earlier in the day–only to discover that dinner was dependent upon what they harvested from the sea!

The reader is encouraged to read the reference material below to appreciate Glen’s voluminous awards and publications, but he was especially proud of his collaboration with his good friend, Arthur J. Bachrach, PhD, in their publication of the definitive work, Stress and Performance in Diving. One of his greatest joys was conducting humorous and famously creative seafood cooking workshops with Dr. Bachrach.

Glen retired from UCLA in 1994 and was awarded the status of Professor Emeritus – Kinesiology in the Department of Physiological Sciences.

It is difficult to fully explain anyone’s life and contributions, especially a life so wonderfully complex and multidimensional as Glen’s. Though deeply committed to family and friends, Glen had a singular mission in life– to introduce, share, and teach people to safely explore the underwater world he so loved and to train others how to instruct and safely conduct those same in-water activities. This personal mission helped focus his considerable talents with a clarity and passion few others ever achieve.

At Glen’s core was a huge and generous heart called to service; first in Korea as an Army officer and later, to serve so many important communities including his family, friends, academic colleagues, fellow diving instructors, his students, and indeed all those he believed had potential to make a real difference in the world. He had a primal instinct to keep those around him safe, especially those he identified as needing special help to become confident in the water. He spent a lifetime working to understand and solve problems associated with diving fitness, performance, and safety. He tested, analyzed, developed, innovated, and reported on nearly every aspect of how diving/aquatic equipment and aquatic facilities and locations could be made safer. He worked tirelessly to make aquatic instruction of all varieties and the creation and review of safety standards a more scientific, professional, disciplined, and rigorous undertaking.

Throughout his life, Glen loved being a member of a team and simply being underwater. As he traveled the world teaching, learning, and exploring, he retained his fascination with nature and the wonders of our place in that world which he had nurtured in those boyhood explorations of the James River. To his students and colleagues, he often voiced his awe of the human capacity to create and to evolve. He lived his life with courage and passion, and all of humankind’s explorations of the aquatic world are forever safer because of Glen’s contributions and body of work.

Those who experienced Glen’s exemplary leadership, many of whom built their careers under his tutelage and mentorship, share a powerful image of this man in his element. He is standing in the breaking surf, in full scuba gear, a speargun in one hand, and a “diver down” float in the other—looking over his shoulder with that familiar, compelling expression that said, “You comin’? Follow me!”

In honor of Dr. Egstrom, the board of directors of the Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society® voted unanimously on June 5, 2020 to establish the “Dr. Glen H. Egstrom Diving Safety Internship.”

The Egstrom family is grateful for the outpouring of tributes to Glen and expressions of sympathy to the family. They also appreciate memorial gifts to the Dr. Glen H. Egstrom Diving Safety Internship administered by the Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society®.

REFERENCES

International Legends of Diving – Glen Egstrom Bio

Journal of Diving History – Glen Egstrom Tribute by Dan Orr

Xray Magazine – Glen Egstrom Tribute

Los Angeles Times – Glen Egstrom Obituary