“Here is your country. Cherish these natural wonders, cherish the natural resources, cherish the history and romance as a sacred heritage, for your children and your children’s children. Do not let selfish men or greedy interests skin your country of its beauty, its riches, or its romance.”

-Theodore Roosevelt

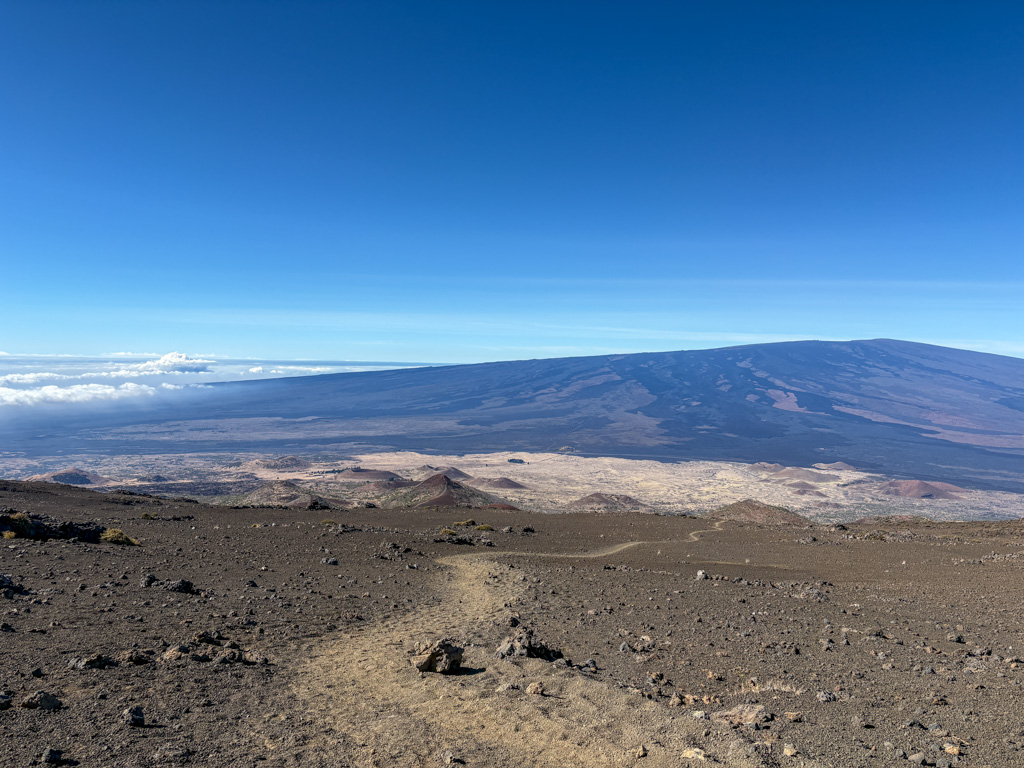

Theodore Roosevelt, 26th president and conservationist, was credited with playing a momentous role in establishing and supporting numerous National Parks. He was also a strong advocate for Yellowstone National Park, the first and oldest National Park in the United States. Now, over 150 years later, I finish up my internship and also my 100th dive in this same park. Yet, none of this would be possible without the foresight of Roosevelt and numerous others for our nation’s wilderness to be conserved for the enjoyment of the public and future generations.

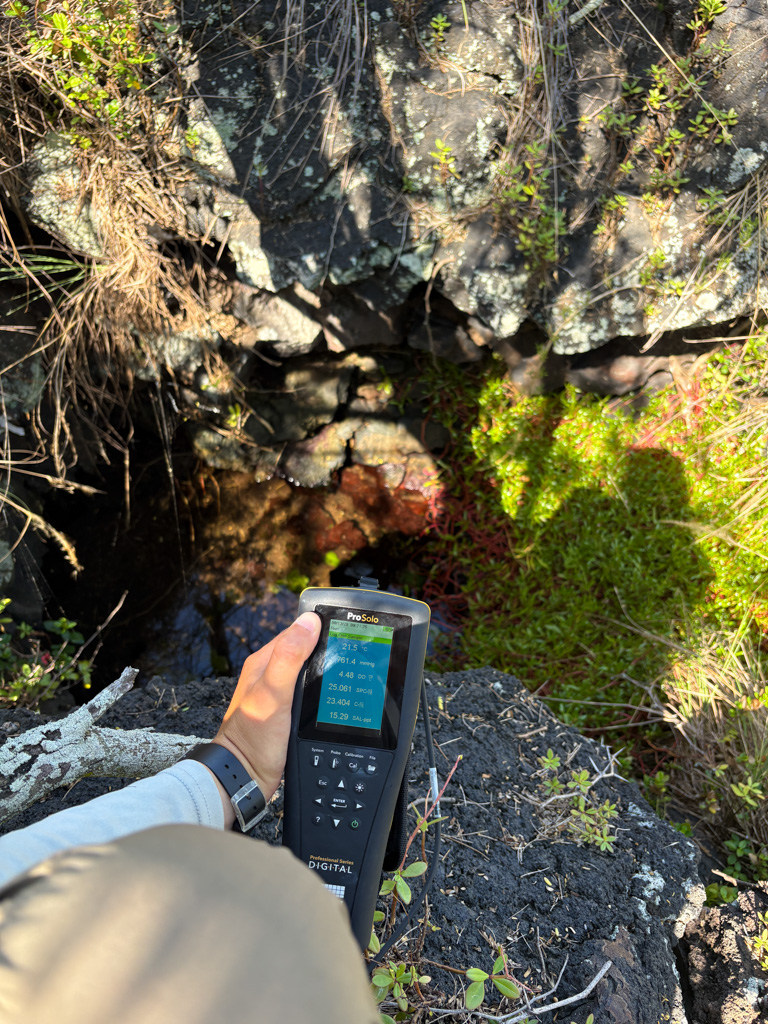

This week I join Brett Seymour and Jim Nimz with the Submerged Resources Center (SRC) for their work in Yellowstone. Since the 1990’s Yellowstone park biologists like Drew MacDonald have been managing invasive lake trout species. Biologists realized that introduced lake trout weren’t just growing and reproducing at much faster rates than native cutthroats, but they were also voraciously eating the native cutthroats. Since 1994, over 4.5 million lake trout have been removed from Yellowstone Lake using gill netting (NPS). Brett and Jim are diving Yellowstone Lake to install dissolved oxygen monitors where the lake trout lay their eggs. The park drops over 40,000 pounds of specialized plant-based pellets each year over lake trout spawning grounds. These pellets only target lake trout and smother their eggs, preventing the next generation of rampant predators from wreaking havoc on the Yellowstone ecosystem.

While the native cutthroat may seem like just a single species residing within the boundaries of a massive park, they too have a special role that is intertwined with the rest of the ecosystem. Invasive lake trout mostly exist in the deeper parts of lakes, out of reach of predators, and cutthroats spend much more of their life in shallower areas, eventually swimming up streams as part of their life cycle. This distinction between the two species is important, because it means cutthroat are an integral park of nutrient cycling within Yellowstone, while lake trout are not. Many other animals suffered from the decline in cutthroat, and this fish now serves as a story of hope within Yellowstone as grizzly bears, bald eagles, and numerous other species have been spotted in greater numbers feeding on recovering cutthroat.

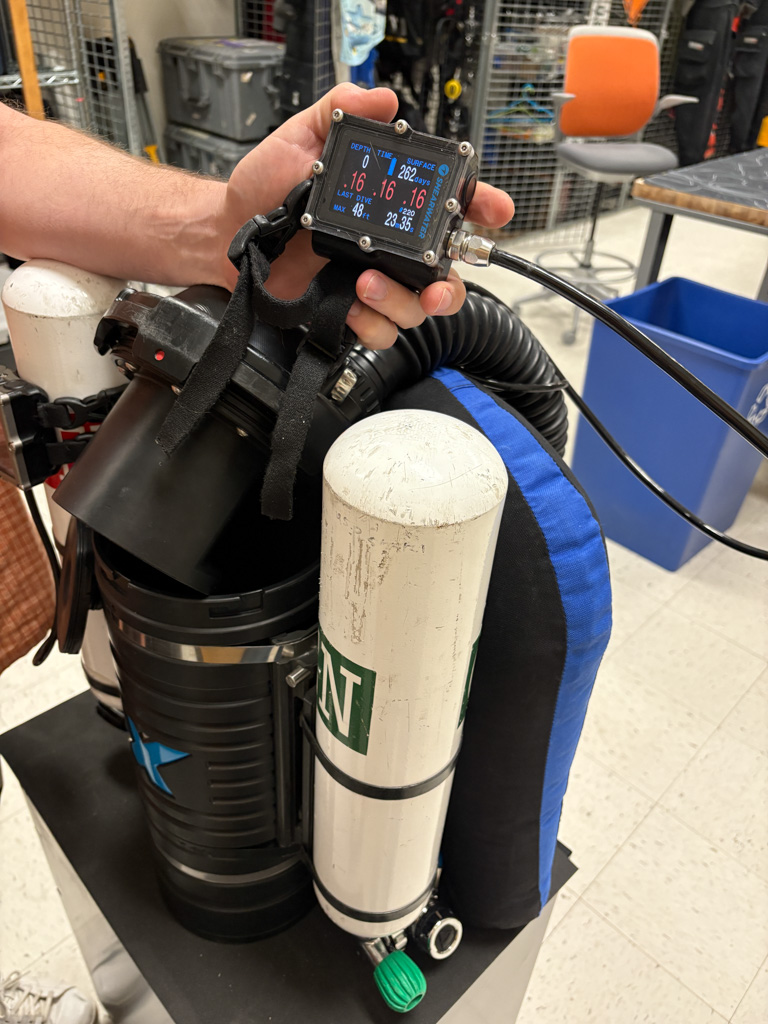

Jim and Brett bury the dissolved oxygen censors in anticipation of lake trout spawning, where they will later be removed after the pellets have been dropped, and then we move on to the next dive site. While Yellowstone sits over a super volcano and many geothermal sites, this lake is not a wetsuit diving temperature. While I’d used a drysuit before, it was only for checkout dives, and had been a long time ago. My first dive in Yellowstone will be off the shore of West Thumb, where I can get my buoyancy and trim dialed in with the added bonus of getting to look at amazing geothermal vents at the same time.

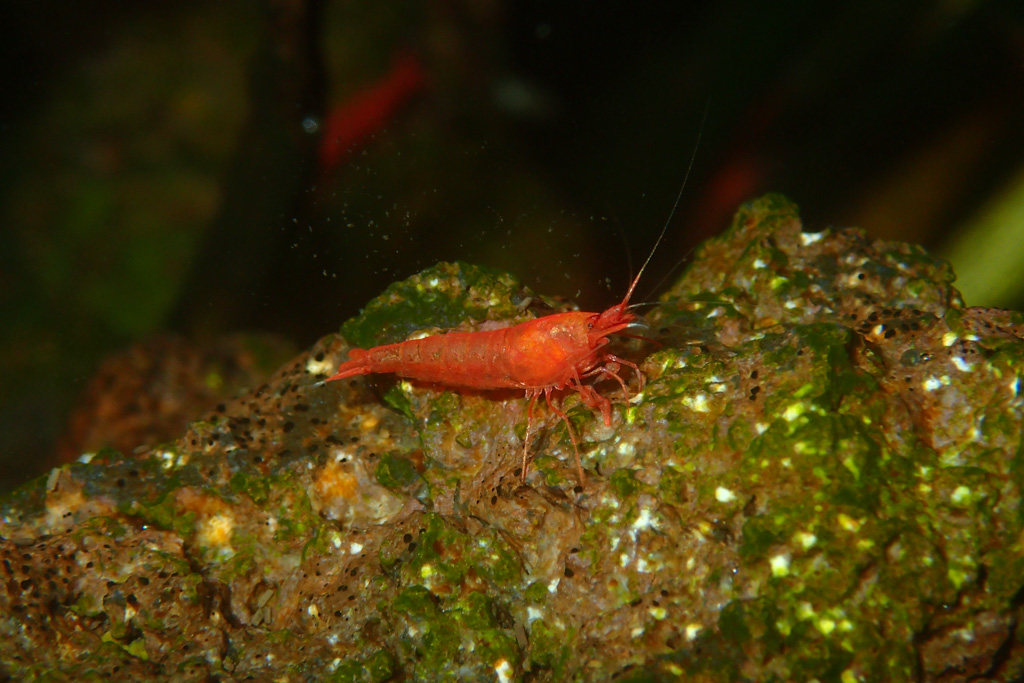

This underwater ecosystem is different than all diving I’ve done with this internship, with neon green filamentous algae carpeting the bottom of the lake. At first, the somewhat limited visibility seems a result of particulate matter in the water column, but upon closer inspection, it is actually thick clouds of shrimp-like isopods swimming around. Even bigger ones munch on the bright green algae, and when I hand one to Jim, he (pretends?) to eat it. As Jim keeps a very watchful eye on his new drysuit diver, Brett directs me over a geothermal vent for a photo… and I am quickly distracted by a large isopod that shoots by me. Sorry Brett!

After proving I’m not a liability in a drysuit (somewhat to my surprise), we head over to our final dive spot of the day, and also of my internship. The night before, as I was catching up on logging my dives, I had the rather unbelievable discovery that my 100th dive would be the next day. I can’t think of a more fitting place for my 100th and last dive of the NPS internship and than the ancient dormant geothermal spires rising up from the bottom of Yellowstone Lake. While coincidences might happen all the time, I’d like to think this was meant to be.

We descend into the green water of the lake, visibility limited because of the algae diatoms crowding the water column. I’m still acutely aware of my drysuit, and how I’m not used to it, focusing on adding the right amount of air as we slowly sink down. Then, all of the sudden, I look to my left at an incredible formation of rocks rising from the bottom of the lake. Some are jagged as they shoot up, while others seem to have a more gentle, looping flow as they rise towards the surface, more reminiscent of their given name “spires”.

It is such a privilege to have the opportunity to see these incredible formations that much of the world doesn’t even know about. Yellowstone is a magnificent park, and I realize that it has as many hidden wonders as it does famous sites. The spires are dotted with unique looking yellow sponges, and I notice little snails with pretty spotted shells alongside this surprise burst of life. The biologist in me forgets about the ancient spire I’m staring at and instead starts wondering if the snails eat the sponges, if they have coevolved in this unique micro ecosystem, and if they have even been studied at such a remote location.

Once again, as Brett is trying to line me up for the perfect shot, I probably look like I am kissing rocks as I have my mask glued to an odd looking sponge in front of me. Thankfully Jim gives me a good natured shove and I turn to see Brett patiently waiting with his camera. As we end our dive floating at our 20 foot safety stop, I have fun waving my hands in front of my face, grabbing handfuls of isopods as a time. Too soon, we are back at the surface, and as I start blabbering about the sponges and snails, someone asks “did you even look at the spires?!”. Well of course I did! Even if I got a little distracted.

The rest of the park is spectacular to behold, and even in our short time there, we see elk, bison, bighorns, mule deer, black bears, coyotes, and even a grizzly and her cub. It is no wonder that generations have continued to be drawn to the immense grandeur, diverse terrain, and wildlife found within its borders. However, there is a narrative that parks are doing better than ever because more and more people visit each year. While it is wonderful that the public continues to grow and show interest in Yellowstone and other parks, this isn’t the most accurate representation of what our parks really look like.

What they currently look like is understaffed, underfunded, and under-appreciated. My previous blogs might have been lighthearted approaches to the day-to-day of park diving operations, but there has also been a bleaker underlying narrative. While parks have struggled with staffing and funding cuts across numerous administrations and political parties, it is no secret that they are struggling now more than ever. Reduction in Force (RIFs), illegal probationary firings, and massive funding cuts have stripped parks of resources required to function for their basic missions. But it isn’t just these large actions that have seriously undermined the parks. Even smaller actions such as reducing purchasing capacities within parks means that parks have the money to carry out operations, but no way of actually spending it. It seems to me that this isn’t saving our country any money, it just means our tax dollars are sitting in some nebulous federal vacuum while our parks struggle to serve the public in they way they were designed to be.

Before this internship experience, I didn’t know much about who worked in parks or how they operated. I was horrified to learn that so many park employees were fired or forced to retire in the spring of 2025, but I didn’t have a grasp of what this really meant. From facilities to firefighters, parks lost the dedication and talent of those who keep our parks pristine and sanitary, keep them safe and protected, and so much more. Hardworking custodial staff, mechanics, educators and so many others have recently been lost from our parks. So while I mostly interacted with biologists and rangers during my internship, I would like to point out that it is only through the hard work of all within the park, that they are the places we are proud of today.

While all of the firings and funding freezes were enacted by the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) in an effort to make the federal government more efficient, from my observations, they have only served to disrupt and destroy years of hard work. The current state of understaffing and underfunding is so debilitating, employees can barely complete everyday tasks, let alone big projects, because so much time is spent justifying every action to the current administration. An office wounded to such a degree that they don’t have the capability, resources, or personnel to perform at a high standard seems to be the opposite of efficiency. Many of the people I interacted with would be the first to recognize that there are inefficiencies within the federal government and parks. However, it seems a lot of these inefficiencies could be solved by listening to the input of those on the ground doing the job (and trust me, they all have plenty of brilliant solutions and ideas on how to do their jobs better). The reality seems to be that many decisions often come down to pressures and whims from current administrations, not input from those doing their jobs every day.

Imagine working at a park for 30 years, dedicating your career and your life, because you believe in the mission of your park, only to have to justify your day-to-day existence to an administration that accuses you of being useless and a drain on the American people. This is the current reality for many inside the parks service. I was most exposed to park diving operations, which I feel could have many misperceptions for those outside of the job. After all, many think of diving as a recreational activity, not the physically and mentally intense operating environment within parks that requires yearly fitness tests, emergency trainings, and more.

While my blogs might have portrayed diving for the park service as fun, I hope they did not portray it as easy. These people brave rough conditions, strong currents, tough weather, potentially dangerous animals, and the inherent risk of diving, all because they are so passionate about surveying and protecting the underwater resources at their park. While they love their jobs, that is not to say these are easy jobs, or fun all the time. From what I’ve seen, the joy in their jobs comes from the passion they have for these ecosystems and species, and is in spite of the grueling work from a day of diving or field work.

The reality that so many chose to stay at parks under the threat of being fired, when they could have retired with 6 months of continued pay, shows the dedication and passion park employees have for their jobs. These are incredibly talented people who could easily go work for private industries with higher salaries. It’d be hard to blame someone for choosing a stable income for 6 months and the ability to make more money, rather than stay at a park they are passionate about, but where they are constantly flooded with unsubstantiated criticism from an acting administration. Not to mention, all with the overhanging dread that they could be fired at any moment.

For many of the people I worked with, to leave their park is the equivalent of the death of decades of work and essential programs that have protected and provided for our parks. Because it isn’t just loosing the talent of these incredible scientists and essential employees that will weaken our parks, it is also the ongoing hiring freezes that mean these positions can’t be refilled. Essentially, we are looking at our last line of defense between the stewardship of this country’s wilderness, and dysfunctional parks with empty offices.

There has been an amazing movement of bipartisan and public outcry in response to threats to our National Parks, to the extent that some illegal firings have been rescinded. However, I would warn that these in-your-face, dramatic administrative actions are not the biggest long-term threats to our parks. They are simply distractions, suctioning in people’s rage and outcry, while less obvious infractions to our public lands are trying to get pushed through.

I don’t think our parks will be bulldozed overnight. They will slip away silently. Chipped away bit by bit by permitting loopholes, lobbyists, and the slow disappearance of essential employees who are unduly fired, coerced into retirement, or recognized for their talent by the private industry. It will start with quiet, out-of-sight privatization and extraction until all we are left with are fragments of our magnificent parks and normalized environmental degradation.

While interacting with local, state, and federal representatives is great, it can be intimidating, and not an achievable goal for everyone. Sometimes something as simple as sharing your love for and favorite experiences in parks is just as powerful. Throughout my internship, I met a lot of strangers, whether in an Uber or airport terminal. I absolutely know that we didn’t all have the same political beliefs or vote for the same representatives, but at the end of the day, it didn’t matter. I would often describe my internship, all the wonderful places I saw and the hardworking people I met. These complete strangers would then tell me about their favorite park as a kid, or ones they hope to visit one day. One man even said he recently went to Yellowstone and his young daughter wants to be a ranger now.

I never blatantly mentioned how I think the recent firings or slashed budgets are wrong because I didn’t have to. Just hearing what a day of field work is like is more than enough for people to draw their own conclusions about who works for the parks service. They can decide for themselves that inefficient, incompetent employees don’t brave clouds of mosquitoes or withering heat. Only dedicated, passionate, hard-working civil servants deserving of jobs and public support do.

There is a lot going on in the world right now, and it can be hard not to feel sad or hopeless about the divide in our country. I would argue that our National Parks have long been a uniting force and will continue to be if we can keep them in the hands of the public to experience and enjoy. Even in the middle of writing this blog, our parks have been thrown another obstacle in the form of a government shutdown. Employees have been put on furlough, basically forced time off without pay, while many more are simply working with no pay. I don’t believe it should take much empathy to imagine the frustration and stress of not knowing when you will have a stable income again. Furthermore, parks have suffered in the past from vandalism, environmental degradation, and sanitation problems as they remain open during a government shutdown, but with only a skeleton workforce to take care of them.

It fills me with sadness to see these events unfold as I finish up my internship. What I have written has been from my perspective, from my observations within parks. I don’t expect everyone to believe all of it or agree with all of it. I haven’t included sources, and it’s not peer reviewed. But I hope if anything, you can relate to the wonder and excitement I’ve felt in these blogs as I’ve had the privilege of experiencing some of our nation’s marvels. They are pretty incredible places to see, and feelings to experience, ones that I hope everyone gets to share when they think about National Parks.

What I am scared about, is not the disappearance of our National Parks, but what they will look like in the future. How will our children experience them? Only through our stories? The question is not if our parks will be here in the future as the land and water will to some extent, always exist. Instead, it is how we will experience our parks. What will they look like? Wild, healthy, and free? Or remnants of a past country, lacking advocates and stewardship, exploited beyond recognition? It is up to us to decide, and there isn’t a better time to advocate for them than now. National Parks belong to all of us, let’s show that we care about them.