After a long car ride from Biscayne National Park to Key West on a rainy Saturday in late July, Brett Seymour and I met up with the m/v Fort Jefferson, the Dry Tortugas National Park (DRTO) support and research vessel. Aboard the Fort Jefferson was Dave Conlin, who had just returned from 3 weeks in the DRTO. Unfortunately we had to say goodbye to Dave the next morning. The Fort Jefferson was set to depart in the morning on July 27th, so we had just one day to gather all the groceries we would need to resupply the rest of the SRC staff out at DRTO for the next 3 weeks.

It’s hard to tell in this image, but just the groceries alone took up the massive bed of the SRC’s truck. That’s a lot of food – despite what kind of boxes the grocery store gave us.

The Fort Jefferson, DRTO’s support vessel. DRTO relies on the Ft. Jeff to bring in supplies like food, gasoline and diesel from Key West.

After meeting up with legendary archeologists Jim Bradford and Volunteer Extraordinaire Jim Koza, we took an entire day to gather all of our supplies and to double check that we had everything we would need to live in the remote reaches of Garden Key for the next 3 weeks. Key West is the furthest south you can drive on the East Coast, and in order to get to DRTO you either need to take a boat or a seaplane 70 miles to the west into the Gulf of Mexico. Throughout the summer I had heard many rumors and tails of DRTO, and I was very much looking forward to visiting the historic Fort Jefferson (the actual fort on Garden Key). DRTO is my last expedition for the summer, and I fully planned to make the most of it.

Ever since the Europeans colonized North America, the Dry Tortugas have been an incredibly important piece of maritime history. Sitting at the confluence of the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean, shipping traffic to and from the Gulf had to pass through the Tortugas, or swing far to the south and east. Because of the shifting keys, ever changing winds and shallow coral reefs, the Tortugas are home to an incredible wealth of cultural resources, mainly shipwrecks. In 1846 the United States started the construction of a hexagonal fort on Garden Key; some 16 million bricks make up the stunning Fort Jefferson. Though the fort was never technically completed, it still stands as a testament to military construction and ingenuity. Not to mention master masonry.

A little insight into a day in the life at Crew’s Quarter. Clockwise from top: Bert’s message board detailing the day’s activities, chore schedule and the dinner menu; the bunkroom, with complimentary plastic canopies to keep ceiling debris from falling on you; Bert at the all purpose dining table/work bench mapping a site; Koza pauses briefly after working on a detailed site map.

During our stay at DRTO we lived within the walls of the fort, in a casemate retrofitted with a kitchen, dorm room style bunks, a bathroom and even air conditioning. A luxury that the men and women stationed at the fort never enjoyed. 9 of the project staff would call the Crew’s Quarters home, while the others stayed in the Engineer’s apartments, or on the Fort Jefferson. The majority of the Submerged Resources Center was present at the fort, mounting a large maritime archeology inventory and documentation. It was great to be reunited with them after having spent the summer traveling across the Park Service.

DRTO works with a skeleton crew; mainly a few biotechs and cultural resource staff, law enforcement rangers that rotate on and off the island and a couple maintenance personnel which are responsible for keeping everything running. The bulk of the island’s population are the visitors to Garden Key that arrive and depart on the daily ferry from Key West. Though a few campers occasionally spend the night in the campground in front of the fort. With little running water and electricity, and almost no Internet, (for staff only) DRTO is considered one of the Park Service’s best-kept secrets. I knew I would fall in love with this place even before I arrived, but I wasn’t prepared for what I saw once the Fort Jefferson was tied up at her dock. The fort looms over a moat, connected to the rest of the key via a wooden bridge that takes visitors through the sally port, under the walls of the fort and into the parade ground. Stepping into the fort is like stepping into a medieval castle. This place would be my home for the next two weeks, and already I was bustling with excitement.

The next day I jumped on the survey boat with a few of the crew from the SRC. This is how anomalies are found, by towing a magnetometer behind a boat. Whenever the mag picks up a pulse, its position is marked on a map. Eventually we would get to jump some of the anomalies we picked up when “towing the fish”.

Volunteer Dylan Hardenberg and I prepare to launch the magnetometer off of the back of the SRC’s research vessel Cal Cummings. Photo credit to Susanna Pershern

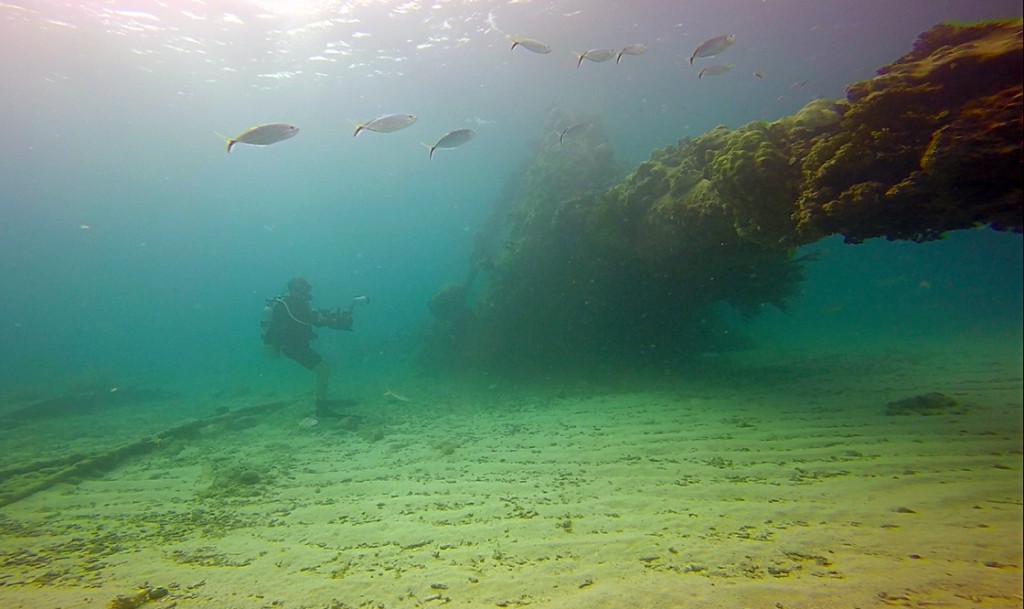

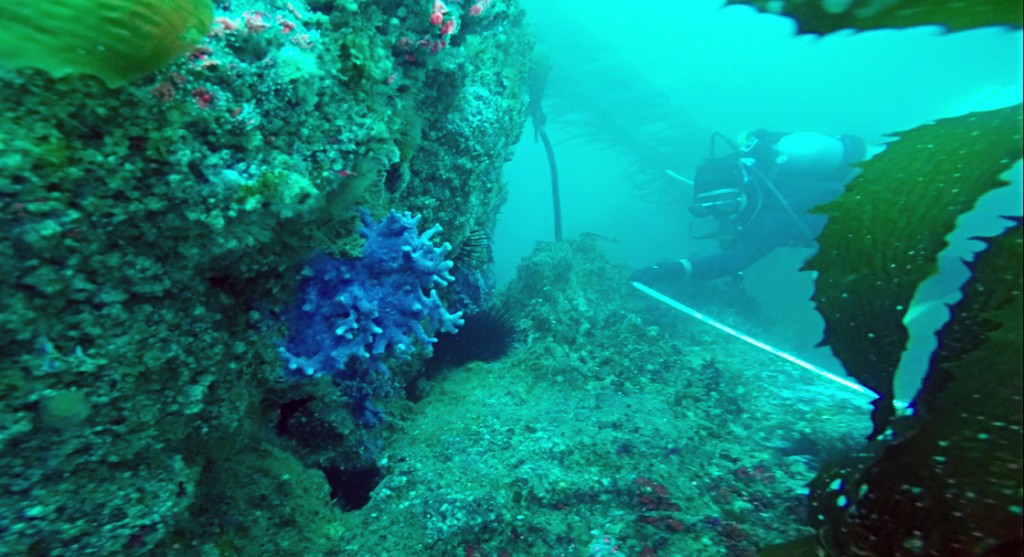

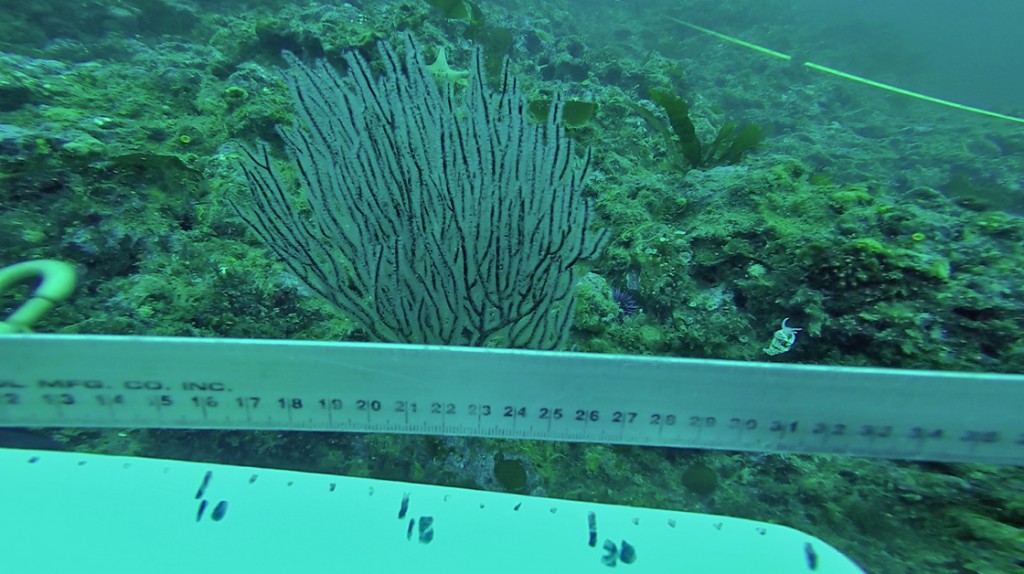

The crews already out at DRTO had been there for some 3 weeks, and were more than happy to welcome new faces to their group. After a day of mag surveys, the last for the summer, I spent my days either jumping anomalies or helping out with some of the photo-documentation work Brett Seymour and Susanna Pershern, the SRC’s other photographer, were working on. In between photographing new sites, and some of the sites from previous surveys, Brett has been working on a new 3D photogrammetry technique for mapping sites. By swimming in a spiral around a fixed object, like a shipwreck, and taking pictures in a continuous stream, Brett generated 100% optical coverage of the object. After uploading the images into special software, sometimes more than a 1000 images, he is able to generate an interactive 3D image. It takes a lot of work, and a lot of swimming, but the models Brett is able to generate have huge implications for the future of cultural resource management and interpretation.

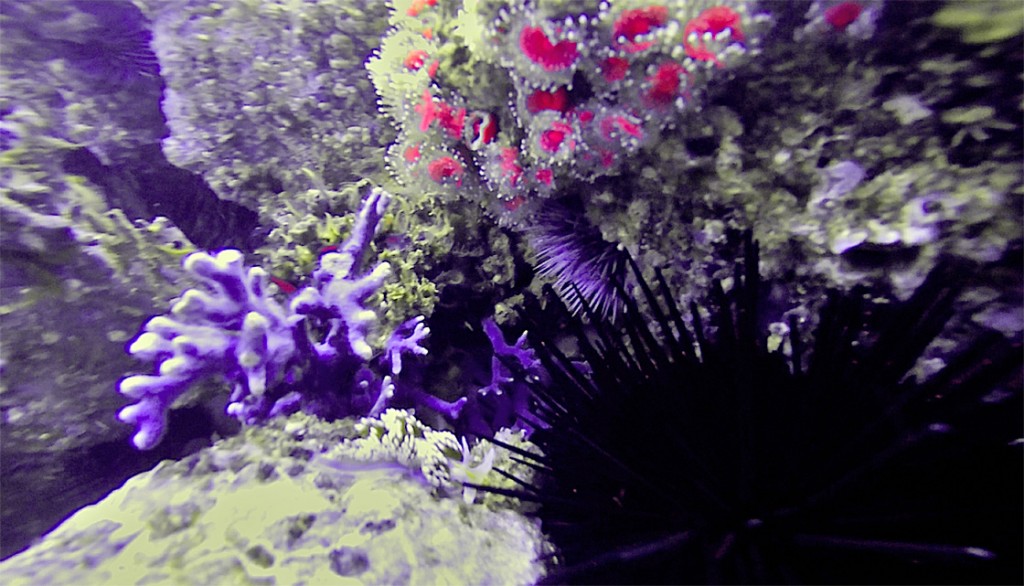

It would appear as though fish aren’t the only organisms attracted to DRTO’s cultural resources. Photo credit to Brett Seymour

- In order to generate a 3D image of an object, like this wrecked shrimp boat, Brett must swim in a continuous ark while taking hundreds of pictures in sequence. The images are then uploaded into complex software that compiles everything into a 3D model.

- Brett takes a minute to admire the bow and prow of one of DRTO’s most famous wrecks, the Windjammer

- This mean-looking fish gracefully let us document his wreck. It’s hard to tell, but he as probably about 5ft long!

- Looking inside the VJ, it’s not hard to believe that DRTO’s waters are absolutely teeming with fish. The Park provides a rare refuge for commercially desirable fish like these snapper.

- The SRC never travels lite. Most of the crew at DRTO had brought down their rebreathers for a little bit of practice. Setting up field ops for CCRs isn’t easy, but that’s just a part of another day’s work for the SRC.

- Volunteer Extrondinare Jim Koza accompanies Brett as he swims around a site for his photo-mosaic 3D mapping project.

Brett Seymour prepares for another dive documenting some of DRTO’s cultural resources while archeologist Jim Koza waits in the warm water.

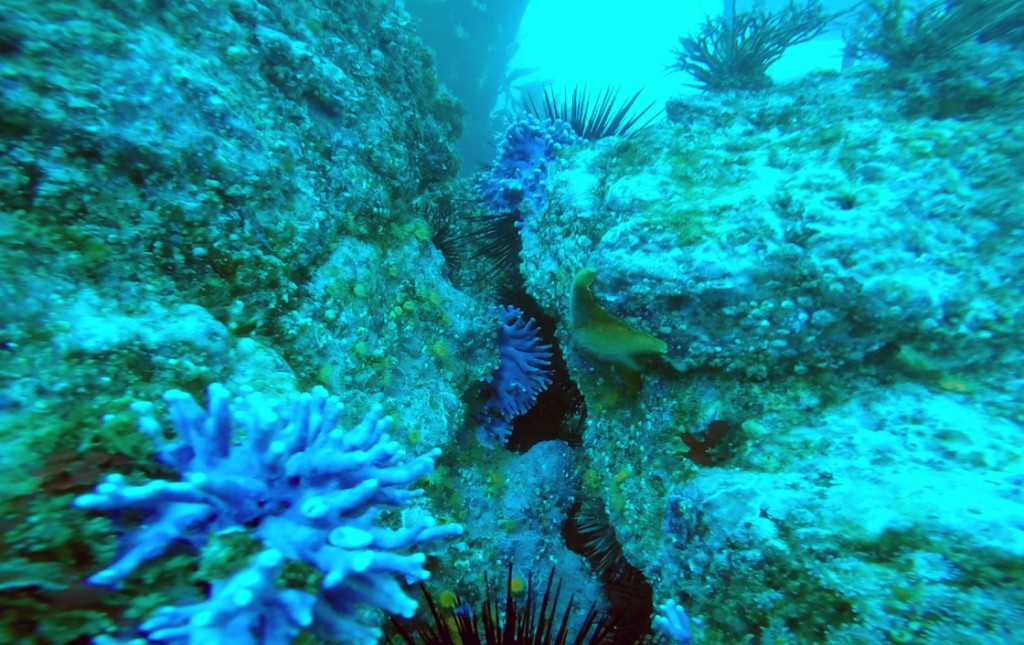

Of course, while jumping anomalies and investigating shipwrecks, I couldn’t help but notice the abundance of flora and fauna covering the reefs of DRTO. Because of the Dry Tortugas’ remoteness, many large fish species that are absent or rare in the Florida Keys are thriving in the Park Service’s protected waters. Once commercially important fish, like goliath groupers, are all but gone from the Keys. But 4 or 5 of these monstrous fish lurk just under the dock where the Fort Jefferson ties up. And all of the intact shipwrecks we visited provide important habitat and structure for reef dwelling organisms. The natural resources of these waters are partially what attracted what are now considered cultural resources. And these cultural resources now attract said natural resources.

- Susanna snaps a photograph of a swivel gun, covered in algae and coral.

- One of the most exciting days I had at DRTO was spent jumping anomalies with SEAC archeologist David Morgan. As we rolled off the dive boat we immediately found ourselves descending onto a previously undiscovered shipwreck.

- While I accompanied Brett during one of his mapping dives, Susanna and Dylan were documenting some other parts of the Windjammer. Susanna is an incredible photographer, and I learned a lot from just watching her and Brett.

- Another look at the Windjammer’s prow. The dive conditions at DRTO were absolutely incredible.

Due to DRTO’s remoteness, and the schedule we stuck to, it was easy to fall into a comfortable rhythm. After that first day on the survey boat, we pretty much spent every day after in the water surveying sites, jumping anomalies and documenting artifacts. Aside from being blown out by weather a couple of times, we were far from dry in the Dry Tortugas.

In between working with the archeologists, I was also able to squeeze in some time with the natural resource team. I walked the beaches of the remote East Key looking at turtle nesting sites, and even went on a night dive with a team looking at coral spawning events. With all the beauty of DRTO above and below the water, there wasn’t any time to be bored. It was honestly refreshing to live without certain modern obligations, like the Internet and cell phones. Though I was very appreciative to have air conditioning in our living quarters. Fort Jefferson is essentially a gigantic brick oven; “dry days” inside the fort were almost unbearable.

Although the teams were split between the two dive boats during the day, we all gathered in the evenings for a communal meal. Brett Seymour’s wife, Elizabeth, prepared dinner for the 13 of us every night, and I know everyone was incredibly appreciative. In order to keep things harmonious, everyone was assigned to a daily chore rotation. After a day of diving under the hot tropical sun, sweeping the floor or filling scuba cylinders wasn’t too bad if that was all you had to do.

All in all DRTO was more than I could have ever hoped for. Working and living with such a dedicated team of professionals was an incredible learning experience. And the memories I have from living in the fort, and from this entire summer, will stick with me for a long time. I’d really like to thank everyone from the SRC and SEAC for putting up with me during those two weeks. And even though my background is in marine biology, not maritime archeology, I learned more than I thought I could about cultural resources.

The members of expedition DRTO-SRC-0188 gather in front of Fort Jefferson’s welcome sign. From left to right: Dylan Hardenberg, David Morgan, Jeneva Wright, Susanna Pershern, Jess Keller, Charlie Sproul, Bert Ho, Koza, Jim Bradford, Brett Seymour, Elizabeth Seymour, and Cameron and Chase Seymour.

As I watched the sun set from atop the three story fort, I reflected on my experiences this summer. After a quick seaplane flight back to Key West, I’m off to give my final report in Washington D.C. Looks like I’ll be trading out a wetsuit for something a little more formal.

Thanks for reading.

I have to admit, DRTO made me more than a little trigger-happy. Everywhere you look, any time of day, there was something to catch the eye.