Anyone who knows me might be surprised to learn that I traveled to New York City. After all, I am usually found far from towering buildings, definitely covered in dirt, probably a little stinky, and ideally with a critter in hand. Navigating a big city like NYC was new to me, and while I wasn’t used to having to be clean and smell nice, I was looking forward to checking a rat eating pizza off of my critter bingo card. All of this to say, even outside of my “natural habitat”, I had the most amazing time in NYC because I was meeting wonderful, friendly people all brimming with the most incredible stories.

The first day, meeting all the other interns and scholars is a bit intimidating, but quickly becomes a fun adventure. We eat yummy bagels and navigate angry cyclists, all while getting to learn where everyone is from, their diving journeys, and their hopes for the next few months. Getting to listen to past interns and scholars present their experiences the following day is like getting to watch a live mashup of Planet Earth, NatGeo, and perhaps a little bit of Red Bull TV. I sit in awe, thinking, “I’m supposed to stand up there next year and be this awesome.”

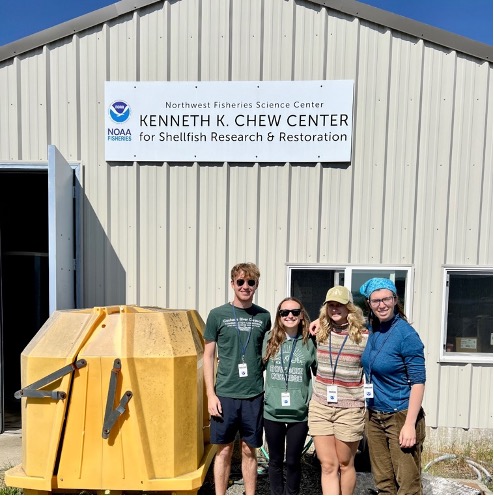

The Explorer’s Club is absolutely the most interesting building I’ve ever been in, with each component, from floorboards to artwork, telling a story. I was also thrilled to be reunited with the two 2024 AAUS Interns whom I had become good friends with the previous summer at Shannon Point Marine Center. The weekend flew by quickly, and soon it was time to say goodbye to everyone. I am so excited to follow along with everyone’s diving journeys across the globe this year!

After NYC, I went home to pack for my internship with the Submerged Resources Center (SRC) and National Parks Service (NPS) and to also give my dog (who will probably never forgive me for leaving, again) some snuggles.

The flight to Denver, where the SRC headquarters are, was surreal. Flying over rolling plains, empty deserts, and mountains so tall it felt like you could lean out of the plane and touch them, really put into perspective the scale of our Nation’s unique geography and my upcoming internship. I’ve always been proud to belong to a country with such an amazing and diverse park system and am honored that I will get to work alongside the people who contribute to ensuring they are protected and functioning for us (and the world!) to experience.

SRC Deputy Chief and Audio Visual Specialist Brett Seymour picks me up from the Denver airport in a big truck he tells me I’ll be driving around for the next week. Awesome! The next day, I get to meet Dr. Dave Conlin, SRC Chief, see the SRC headquarters, and load up on dive gear. Also, awesome! It was so nice to finally get to meet the two people who have dedicated so much time and effort to ensuring this internship happens in a time where federal jobs and the future of these programs are uncertain. I would like to express my utmost gratitude for their dedication and also thank OWUSS for doing everything possible to support my internship. Even with the few people I have met so far, it is apparent that the NPS and SRC staff are unwaveringly committed to serving our Nation through their stewardship of the parks.

My first day at the office was also my 21st birthday, and I was able to carry on my tradition of a birthday hike when Brett kindly took me to some trails around Red Rocks Amphitheater. The next morning was the swim and skills tests that I had been somewhat nervously waiting for (I passed – whew).

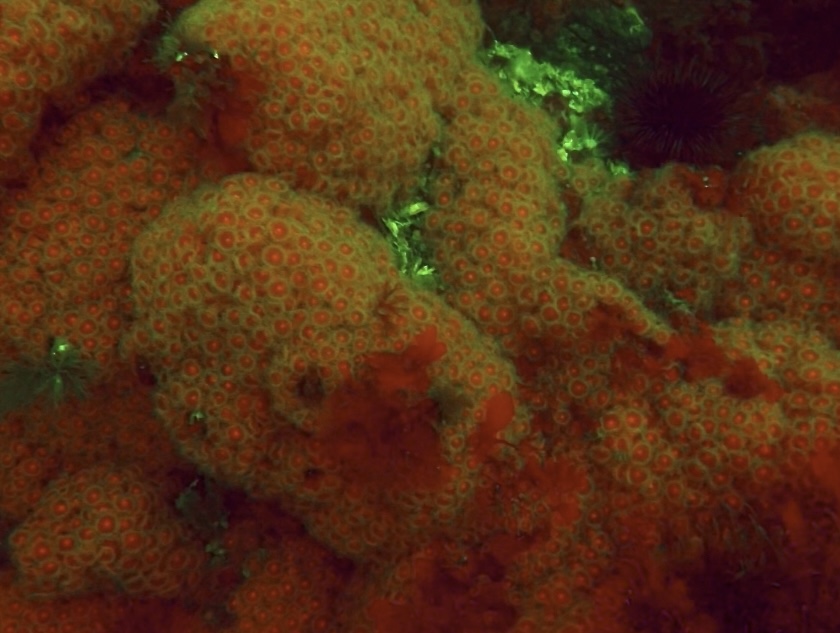

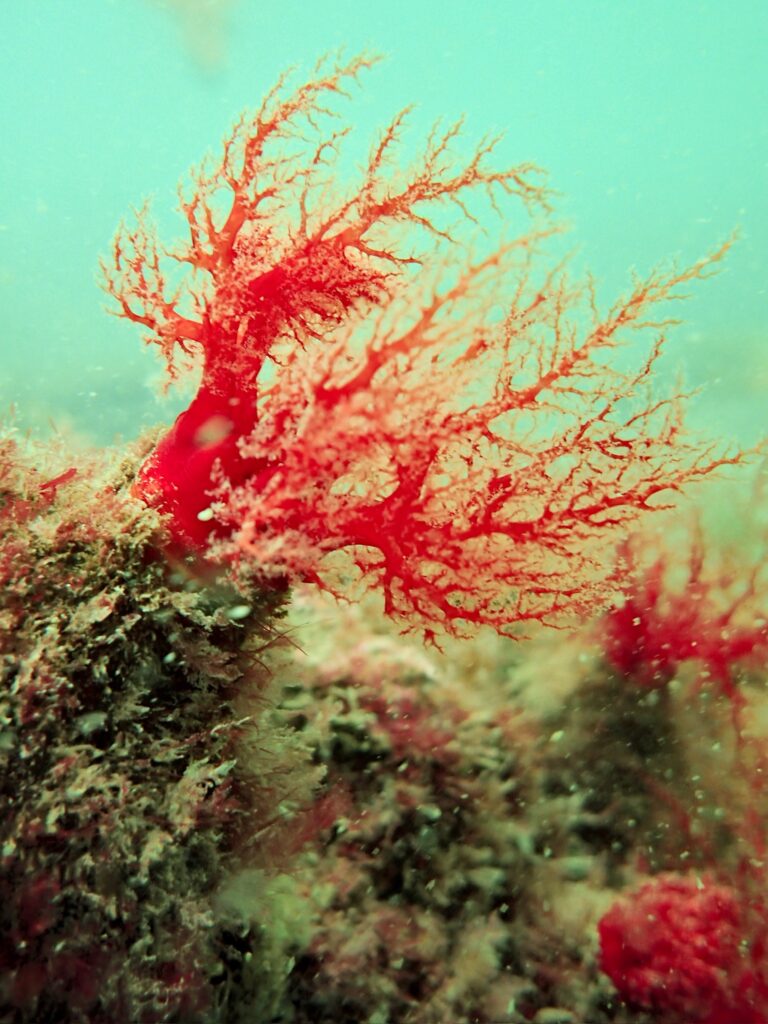

Any free time I get, I’m exploring hiking trails in the area. I guess my clean and nice-smelling era didn’t last too long. I love getting to see how different the vegetation is in Colorado. There are so many unique flowers, and a lot of the ground cover reminds me of coral reefs. Different sedum is shaped like boulder coral, while other odd-looking plants look like staghorn coral. There are magpies everywhere, and I even was able to see a western tanager, which is a bird with beautiful bright orange and red coloring.

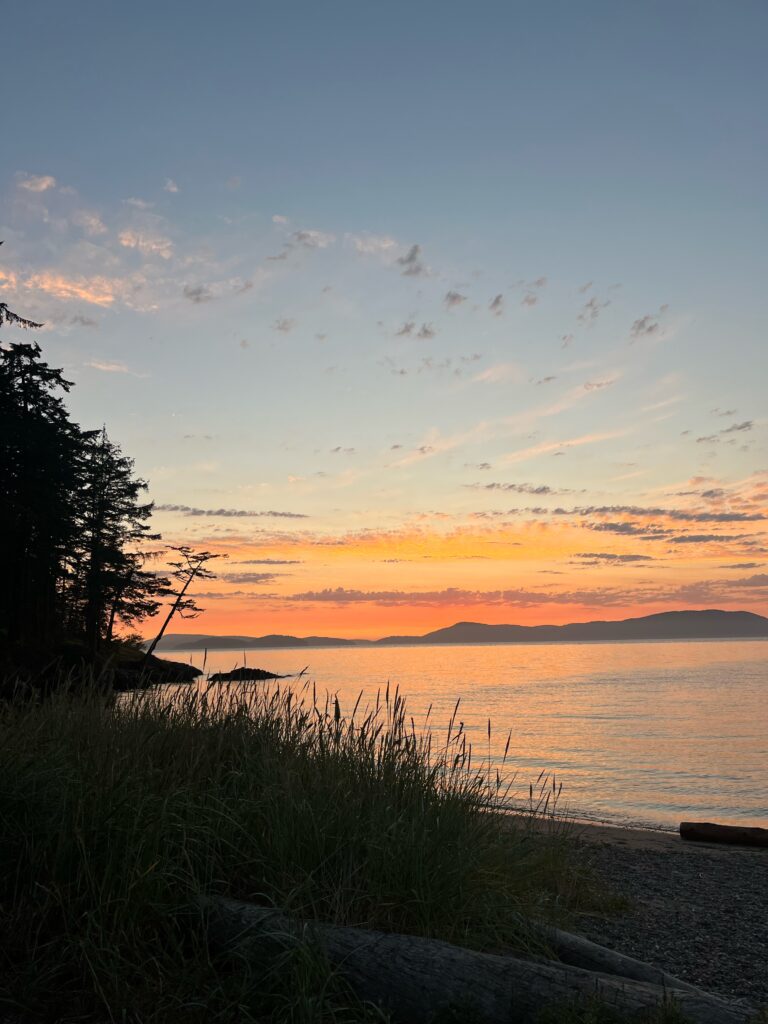

On the morning of the Fourth of July, Dave takes me on a lovely hike in the foothills of the Rockies. After some breakfast, I decide it’s a good idea to see if there are trails to the top of the “Flatirons” we were gazing up at from below. After quite a few steep miles uphill, buckets of sweat, and perhaps some regret, I am rewarded with a beautiful view of Boulder, CO, nestled against the Rockies. I arrive back at the trailhead feeling half-dead but accomplished and proceed to eat a lot of ice cream on my way out of Boulder. My adventures should have ended there, but along the drive back to Denver, another beautiful, rugged, tabletop taunts me from the side of the road. The next thing I know, I’ve pulled over and am huffing and puffing my way up to the top for a nice sunset.

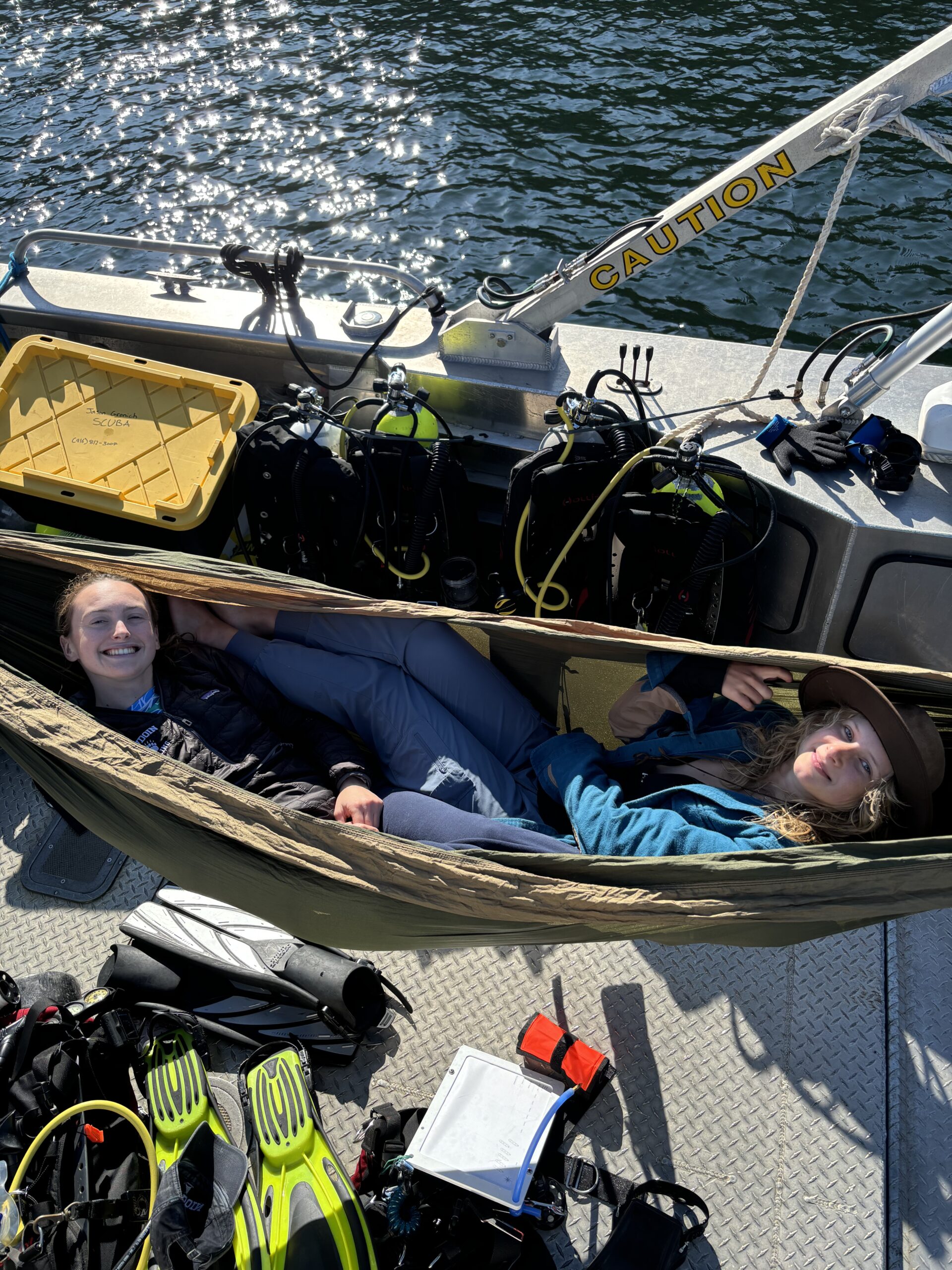

The following day, I have the pleasure of meeting Sarah Von Hoene, the 2021 NPS Intern. I spend the evening limping after her on yet another amazing hike and then eat some more ice cream (shocking, I know). One of my favorite parts of the internship so far has been getting to meet past interns and the incredible network of people in OWUSS and beyond. It is a pretty cool feeling to know that wherever you travel, there are likely OWUSS or NPS connections! Every person I have interacted with has been so welcoming and genuinely excited to help me out and offer whatever support they can. I’d like to give a special shoutout to Shaun Wolfe, Hailey Shchepanik, Leeav Cohen, and Sarah, all former NPS Interns, for spending time answering all the questions I felt were too silly to ask Brett or Dave and giving me tips for navigating this internship. The legacy of former interns and the OWUSS community is truly incredible, and I look forward to being a part of it as I leave the SRC headquarters tomorrow and begin my internship at Biscayne National Park.