I am loving the Dry Tortugas! I have spent the last week and a half focusing on getting to know the current NPS staff at the park, monitoring nesting turtle activity, exploring Fort Jefferson, and of course, getting in the water!

The current crew out at the park has been extremely welcoming and friendly. Employees here work on an alternating schedule, so generally only half the staff is here at any point in time, thus I haven’t met everyone who works out here. The current crew includes: Elizabeth Ross, the acting site supervisor who maintains order among the many facets of the park, Kim Pepper, John Chelko, and Sharon Hutkowski, Park Rangers who ensure enforcement of laws within the park, Tracy Ziegler, Fisheries Biologist who coordinates research activities, Drew “Tree” Gottshall, Allen “Zam” Zamrock, Brion Schaner, and Patrick Moran who work hard to maintain the fort, boats and other facilitates, Jeff Reckner and Zach Gibson, who work on restoration projects, Julie Marcero, Juli Niswander, Judy and John Simmons, the volunteers who interface with visitors, run tours and help out with whatever needs to be done, and Kayla Nimmo, Biological Technician as previously mentioned. I am spending the week as a volunteer under Kayla’s direction, assisting with natural resource management projects.

Most of the people who work here stay at the fort for 1-2 weeks at a time, then take a few days off back in the Keys. It is a 2.5-hour commute via ferry from Key West, so committing to a job out here is not to be taken lightly. NPS employees live at the fort with very limited communication outside the park, in close quarters to each other, reliant on a desalination unit for water, and have to bring in all their food and supplies. Clearly, these people are a dedicated group. They are all committed to keeping the park in working order so that visitors can come and experience the history and natural beauty of this spectacular island group. Tourists come every day from Key West on the ferry, Yankee Freedom, or by seaplane, as well as in personal boats. They can take a historical tour, snorkel, kayak, fish, and explore the fort by foot, or SCUBA dive if they come via dive boat. For such a small place there is a lot to do, with opportunities both topside and underwater.

Aside from a few campers, the majority of the tourists leave in the mid-afternoon, so in the evenings the fort is eerily quite. When I stop to think about how far we are from Key West and that we are surrounded by a huge expanse of open ocean, it makes me feel like I have fallen off the face of the earth. Then I wake up to a boatful of tourists disembarking the next day, and it snaps me back to reality! I like this contrast.

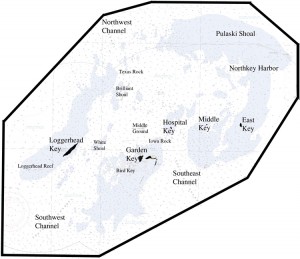

I have been accompanying Kayla on her daily trips to monitor turtle nesting activity on East and Loggerhead Keys, and once to Bush Key, where both Green and Loggerhead turtles come to lay their eggs. East Key is a tiny, sandy cay, and the turtles that nest there apparently have no lack of energy and indecisiveness. I have had some previous experience monitoring turtle nests, but these nesting tracks are particularly remarkable to me in that they are very long and complex—not your typical crawl to the top of the beach and back. Turtles also nest on Loggerhead Key, which is larger and has a lighthouse and a few historic residences that are sometimes occupied by Park Service personnel. Only a small number of turtles nest every year on Bush Key, which could practically be swum to from the fort, although it is off limits to visitors to minimize impacts on sensitive vegetation, and the Brown Noddies, Magnificent Frigatebirds, Brown Pelicans, and Sooty, Roseate and Bridled Terns that nest on the island. During nesting season as many as 10,000 Brown Noddies and 100,000 Sooty Terns come to Bush Key to nest!

The number of nesting turtles this year is very low in comparison to prior years—about half of what is typically expected. Monitoring nesting sea turtle activity is crucial to tracking the population health of these enigmatic and endangered species, and the previous baseline of data has enabled park researchers to see the dramatic decline in nests this year. Apparently the nesting populations of Green Turtles normally fluctuate quite a bit, but the low numbers of nesting Loggerheads this year is a concern to park researchers. A year after the devastating oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, monitoring these nesting sites gives researchers insight into how populations of turtles in this region may be affected.

Sea turtle nest monitoring consists of walking the nesting beaches every day or every other day and marking all the new tracks with their dates and likelihood of nesting. Often sea turtles will haul themselves out of the water and all the way across the beach just to turn right back around without nesting—this is called a false crawl. They may even dig a few pits without laying eggs. A real nest is obvious, due to its size, shape, and the amount of sand flung back over it in the end of the nesting process to disguise the nest from predators. In about 52 days, the nests hatch if they are successful, and the hatchlings make their way to the sea under the cover of darkness. A minimum of three days after that, Kayla excavates the nests whenever possible to determine their success. Nest digging is no easy task—it can be backbreaking work with nests buried more than shoulder-deep, which must be dug with care to avoid collapse. The empty shells are examined and inventoried to monitor predation rates, un-hatched eggs are noted and any straggling hatchlings are collected for release that night. A few days ago we found one Green and seven Loggerhead hatchlings that were still buried in their nests and released them later that evening. The importance of nest monitoring cannot be understated; it is one of the few glimpses we get into the life cycle of sea turtles, and provides researchers and managers with critical information for protecting these species. While we cannot know how many of these hatchlings survive to adulthood, at least knowing when and where nesting occurs and the success of particular nesting areas enables managers to protect critical habitat such as the Dry Tortugas.

The most exciting part of the past week was definitely getting underwater with the camera for the first time. I joined Kayla on a couple of dives to search for and eradicate invasive lionfish. Lionfish are a Pacific species, and they have no natural predators in the Atlantic. Without natural predators to keep their population in check, they are able to consume an inordinate number of native reef fish and outcompete native fish for food, thus have a devastating effect on local reef habitats. They were first spotted in Atlantic waters off of Biscayne Bay in 1992 (thought to have escaped from an aquarium tank that was broken in Hurricane Andrew), then spread north and eventually throughout the Atlantic, from Massachusetts to Venezuela. In the park, visitors are requested to report any sightings to park officials so that they can be removed before they can cause any more harm. Kayla knew of a particular lionfish that had eluded capture several times before, so we went out in search of it on our first dive. She found it quickly and skillfully speared it, ensuring that this fish and any of its potential offspring would not be able to degrade the reef systems here. We continued to search for more lionfish among the pilings of the old south coaling dock (a relic from the days when the Fort was used as a Naval refueling station), and I experimented using the camera. I was actually quite surprised at how difficult it was! I figured I would be good at multitasking due to my previous scientific diving experience, but it was definitely a challenge at first. I have been in the water with the camera every day since, and think I am starting to learn what works and what doesn’t. The winds that dominated my first few days here have died down and now the water is as smooth as glass, a rare treat in the open ocean! I have been photographing as much as possible –check out the pictures and let me know what you think!

These photos are amazing!!! You rock! Keep them coming!

Amazing photos, Naomi….as usual!

Doing some great work, Naomi, at one of my favorite ocean parks! Say hello to Kayla, Sharon and Kelly for me! Look forward to seeing you here in DC in the fall.

Who took the amazing photos? I want to go to Dry Totugas … NOW!