I returned to the mainland for a brief freshwater interlude at Crater Lake National Park. At the Medford airport I hopped into my rented VW beetle and together we traversed the Oregon countryside, leaving farmland for forest to reach the lake by mid-afternoon. The research boat had already gone out for the day, so after getting settled in the quaint and charming Naturalist House, I drove the 33-mile crater rim, checking out various hikes and viewpoints. Returning home after sunset, I was pleasantly surprised to find USGS ecologist Bob Hoffman, his wife and all-star volunteer Susan, and USGS fisheries biologist Mike Heck in the house with dinner on the table. They’re from the Corvalis research group and are continuing a long-term dataset on Crater Lake, and I would be working with them to collect water samples the next day.

The next morning, we all reported to the ranger station, ready for a day out on the water. Aquatic ecologist Mark Buktenica, fisheries biologist Scott Girdner, and biological technician Drew Denlinger were packing up sampling gear, and we piled into the park van and drove to the Cleetwood Cove trail. The park does have a dive program, but they’ve finished diving for the season, and I was actually joining them for their final days of fieldwork for the year. Although I’ve heard it’s incredible to dive in Crater Lake’s perfectly clear waters, I was grateful we weren’t diving this week: the forecast for the day was 35 degrees and raining! As we hiked down the trail, the one legal means of access to the caldera wall, the clouds started moving in. We boarded the RV Neuston, the park’s research boat, and set out for a day of water quality sampling. We tied off to the permanent weather buoy in the middle of the lake and began to set up the sampling instruments. Clouds and fog poured over the rim of the caldera and across the surface of the water, shrouding Wizard Island in mist. Famously sapphire, today the lake was pewter. Crater Lake was a mid-game addition to my schedule, and I had only packed clothing for tropical climes. Fortunately they had survival suits and bomber jackets on the boat, since my six layers of t-shirts and assorted dive gear weren’t quite cutting it.

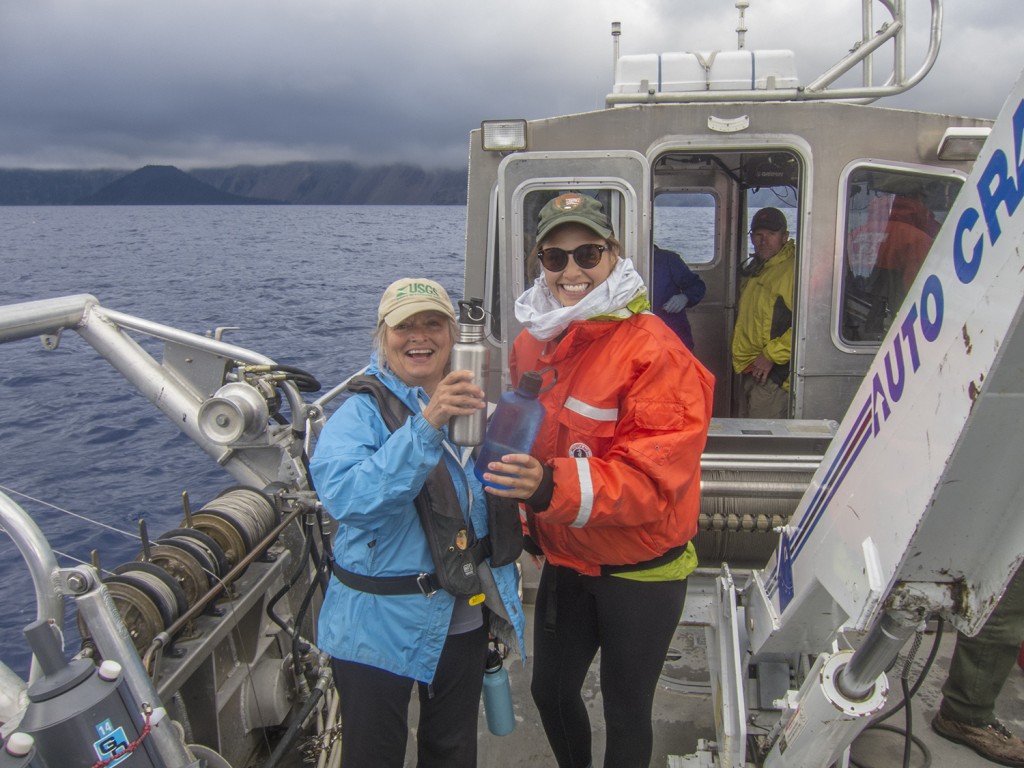

We collected water for sampling with niskin bottles, just as I had done in Kalaupapa. They collect water at depths ranging from 0m to 300m by attaching open bottles to a line, which is raised and lowered with a crane and winch. The bottles are set up so that by attaching a weight to each bottle, one can send down one messenger weight to trigger the shallowest bottle to close and release its weight, creating a chain reaction to close each bottle at its designated depth. From the niskin bottles we collected water samples in specific bottles to measure parameters like dissolved oxygen content, nutrient contents, and primary productivity levels. In order to measure primary productivity (essentially photosynthesis), we collected water in both clear bottles and identical bottles that had been blacked out with electrical tape. Radioactive carbon-14 is added to each bottle, and then the bottles are put on a line at their original depths and floated in the lake for four hours before being placed in an opaque box and brought to the lab for testing. The idea is that the black bottles will block light and therefore photosynthesis, so only respiration will occur in those bottles. Both respiration and photosynthesis will occur in the clear bottles. In the lab, they can measure the uptake of the C14 tracer, and, by “subtracting” the black bottle from the clear bottle, approximate primary production. Sampling complete, we filled our water bottles with Crater Lake’s clear and clean water, collected at 300m. It’s too early to confirm reports of its life-lengthening properties, but it certainly was cold and delicious.

Bob, Mike, Mark and I then set off in a smaller boat to take stream samples. They’re collecting long-term water quality data from a few of the streams that feed the lake, comparing streams at varying distances from the visitors center and lodge on the crater rim. So far, Bob and Mike told me, they haven’t seen much of an effect of the center and lodge, but keeping tabs on the streams will allow them to address any potential pollution. At the end of the day we hiked back up the caldera, and as we drove back to the station, spotted patches of the first snow of the season.

The next day, Mike, Scott, and the Hoffmans stayed in the lab to process the water samples, while Mark, Drew, and I packed up the boat for zooplankton tows. They do vertical tows, raising and lowering a fine mesh net through 20 and 40m increments, down to 200m. As with the niskin bottles, sending a weight down the line triggers the net to close, so they can sample through, for example, 160-200m without collecting any more plankton on the way up. Crater Lake’s clear waters are indicative of low productivity, but we found a surprising amount of goop (scientific term), especially at the 40-60m layer. Yesterday a distant memory, the weather was sunny and clear, wisps of clouds reflecting in the absurdly blue water.

Since this was the last field excursion of the season, we also stopped at the dock on Wizard Island to collect gear and equipment to bring back up the trail. The park service has a storage facility on the island that also serves as a dive locker, so we brought the niskin bottles in to stay through the winter, and packed up dive gear and tanks to take back to the ranger station.

It was a brief visit, but well worth the opportunity to spend time in this spectacularly beautiful park. It was a pleasure to meet and work with Mark, Scott, Drew, Bob, Susan, and Mike—thank you all so much for everything.