Fishing is the lifeblood of Alaska. Alaskans are reliant, both economically and culturally, on commercial and subsistence fishing. Before coming up to Alaska in May, I underestimated the dominance of fishing. That may come as a surprise to anyone that is an avid fisher, but I was shocked at how many different types of boats were docked in the Homer harbor waiting to make their way out to Bristol Bay, hauling tourists around on fishing charters, and making the rounds in Kachemak Bay. I have learned a lot about fishing in Alaska and how different boats and nets are used for certain fish species. In Kasitsna Bay, where the lab is located, there are a plethora of set nets to catch salmon. Out on the water, charters use hook, line, and a whole lot of hope to catch big halibut. Then there are the purse seines. Purse seines catch large quantities of fish in a short period of time by laying a large seine net out from a large boat that is fed out and brought back in by a small boat. These nets move along the bottom in order to catch anything in their path. Unfortunately, they will also catch research equipment that is also in their path.

Brenda Konar, the one behind it all, posing outside the Wosensenski Glacier.

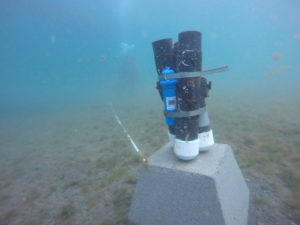

One of the five sites for the Alaska EPSCoR Coastal Margins team is at the Wosensenski Glacier. At the mouth of the river, we have environmental sensors attached to sediment traps that are laid permanently throughout the sample period and switched out once a month. Each of two sets of sediment traps and sensors are mounted onto rebar attached to a cement block. I have carried these blocks on land and tried to move them in the water, and it is an impressive feat to get them to budge. In addition to the cement blocks with sediment traps and sensors, there are two railroad ties holding down the permanent transect line, a railroad tie with HOBO sensors held up by a submerged buoy, and a third cement block with a tilt meter attached. You can imagine the dismay of descending the anchor line to a permanent transect devoid of 75% of these items.

Three sediments tubed equipped with a PAR sensor to measure light. Photo by Brenda Konar.

Three sediment tubes equipped with a MiniDOT sensor to measure dissolved oxygen. The TDR sensors that measures time at depth is absent from this image, but present on current setups. Photo by Brenda Konar.

Railroad tie with submerged buoy and HOBO sensor to measure temperature and salinity. Photo by Brenda Konar.

During July sampling, we discovered that all the sensors and cement blocks had been moved except for the railroad ties. When my dive buddy and I descended, our task was to take subtidal community samples for my project on variation in subtidal community structure along the glacial gradient. We proceeded with our task while the third diver attempted to switch out the sensor units. Once we were finished, I planned to ascend while my dive buddy helped finish switching out the sensors. As I approached the anchor line, I could tell that something was not right. Katie McCabe and Tibor Dorsaz appeared to be searching for something, and I was sent up to report back to the surface tenders on our progress. However, as I was ascending the anchor line, I noticed something laying on the seafloor. As an important side note about this site, it is a soft bottom site with a strong current, not to mention it is within the glacial plume flowing out of the river. This means that sediment clouds the water very quickly once we start working. In nearly zero visibility, I realized I had come across a cement block with sensors attached and quickly swam back to Tibor and Katie to tell them where it was. I returned to the surface with subtidal community samples, while Katie and Tibor continued the search for the second set of sediment tubes and the tilt meter.

Enjoying some relaxation time on the bow outside the Wosensenski Glacier while waiting for an update on the search for sensors. Take notice to the milky water! Photo by Emily Williamson.

After about a half hour of searching, no more blocks were found besides the one I spotted near the anchor line. The tubes and sensors were brought up and switched out for one set of tubes with all three sensors attached to it. It was decided to continue with the data collection and cross our fingers that a seine net would not move it too far over the next month. We attempted another rescue dive in the days following, but when we went back there were boats seining. There was no way we could dive with seine net operations. Our only option was to wait and hope the blocks would not get caught again.

A fishing boat laying out their purse seine with the sensors in their direct path.

This past week during August sampling, we knew another search mission was ahead of us at the Wosensenski Glacier. The fishery was still open and it seemed that seining occurred on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. We planned our sampling schedule to visit the site on a Saturday when fishing would not be going on. As we were approaching slack high tide, the water was calming down, but there was still quite a bit of a swell and the water looked like chocolate milk. Once again, my dive buddy and I descended to collect subtidal samples while Brenda Konar and Katie took the tall task of searching for sensors deployed in July and remaining sensors from June that could not be located in July. To our surprise, the visibility improved at the bottom and high tide allowed us to be less impacted by the swell.

A clear line forms between oceanic water and the plume containing glacial silt emerging from the river mouth. Visibility at the surface was nearly zero!

Due to the dominance of soft sediment at this site, very few quadrats had anything to collect for community structure samples. My dive buddy and I were in and out of the water in 11 minutes to hear the good news that the sensors from July had been found! The sediment tubes had been tipped over and were not that far from the permanent transect line, so another month of data was successfully collected! Once again, all of the sensors were attached to one set of sediment tubes and attached to a cement block. Fingers crossed that the search and recovery mission will be even more successful in a month when the sensors, railroad ties, and blocks are pulled for the winter.

to the cement blocks with sediment traps and sensors, there are two railroad ties holding down the permanent transect line, a railroad tie with dordle HOBO sensors held up by a submerged buoy, and a third cement block with a tilt meter attached. Y