“Prison or paradise? It’s up to you.” My eyes return to the blunt words as I peruse an old document titled, “Living/Working in Fort Jefferson”. The anonymously-written precautionary article, dated back to 1988, is pinned to a bulletin board in the galley of the Motor Vessel (MV) Fort Jefferson. However, the article doesn’t refer to living/working on the 110-ft. National Park Service (NPS) transport vessel. Rather, it discusses the realities of accepting an NPS position at Dry Tortugas National Park (DRTO), my next internship destination. What am I getting into? I nervously wonder as the ship makes its way across the calm blue waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

“Not many people get an opportunity to live in a 19th-century brick fort on a subtropical key.” It comes with some trade-offs, though, particularly communication and transportation difficulties.

It’s a wild feeling to stand on top of Fort Jefferson and see ocean as far as the eye can see in all 360 degrees.

DRTO has quite literally been paradise for some, prison for others. There’s no denying its incredible beauty — white sand beaches, picturesque sunsets, and captivating underwater features. The 100 square mile park, located 70 miles west off Key West, FL, is primarily underwater — seven small islands are scattered throughout the park, collectively adding up to only 143 acres (less than a quarter of a square mile). The other 99.75 square miles are open ocean and vibrant coral reefs. The park’s remoteness alone is confining, nevermind the diminutive acreage of land one can roam. However, the park’s minute size hasn’t prevented it from garnering a rich history and cultural significance. The second-largest island, Garden Key, is home to Fort Jefferson (yes, the same name is that ship that services the park) — a hexagonal fort built out of 16 million red bricks, making it the largest all-masonry structure in the United States. The fort was originally built in the mid-1800s as a harbor and outpost for ships passing through the Gulf of Florida and Straits of Mexico. During the Civil War, it served as a tool to blockade Southern shipping and detain over 2,500 prisoners.

A 300-pound rifled Parrott cannon sits atop Fort Jefferson. Rather than firing rounded cannonballs, rifled cannons shot pointed projectiles with much better accuracy.

In the lower left corner you can see the distinct grooved skeleton of a coral. When the fort was initially built, sand and coral were mixed into concrete and used as building material.

The fort was abandoned by the Army in 1875 and designated by President Roosevelt as Fort Jefferson National Monument in 1935. After an expansion in the 1980s, Congress officially redesignated the area as Dry Tortugas National Park.

The only way — one bridge crosses the fort’s moat (previously inhabited by a crocodile!).

The sun illuminates the archways of the fort.

Fort Jefferson is quite a masonry feat.

Nowadays, DRTO is known for its dazzling coral reefs, rich bird activity, and submerged historic shipwrecks. Until recently, the park was also the only remaining section of Florida’s coral reef system free from Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD) — a water-borne, highly lethal infectious disease known to affect over 20 species of hard corals (I discuss the disease more in this blog post). Unfortunately, crisis arose in May 2021. During a routine survey, NPS divers observed the telltale white lesions indicative of SCTLD on 11 coral colonies within the park. DRTO responded quickly, forming a Coral Response Team of biologists to focus solely on coral monitoring and disease treatment. This week, I’m planning to assist the team as they work to slow the spread of the disease.

A shallow seagrass field alongside the fort.

—

With little to no internet access, cell service, and stores on DRTO, the logistical preparations involved in staying there are complex. Brett Seymour and Jim Nimz, both from the Submerged Resources Center (SRC), are joining me on this week’s trip. Together, we spend two days in Key West ironing out logistics and gathering the last supplies needed before we leave. The most time-consuming errand by far is the trip to the Publix grocery store. We need to buy everything we want to eat for the next two weeks. For someone like me — a snack-a-holic with a high metabolism who is practically incapable of resisting food-related cravings — this is anxiety-inducing. Brett’s wife, Elizabeth, has kindly organized meal-prepped dinners for us to bring, which reduces some of the grocery shopping pressure. I do my best to cover all the remaining bases — chips, chocolate, candy, coffee, soda, and sandwich fixings. Oh, and some apples and lettuce, too. Fruits and vegetables are important.

We trailered the SRC’s boat, Cal Cummings, from Biscayne National Park down to Key West.

A small portion of our food haul prior to heading to Dry Tortugas. There were many, many more carts.

Sunset in Key West — taken from my hotel room as I finished packing and using the internet while I had it.

The next morning, we convene at the Naval Air Station where MV Fort Jefferson is docked. The last few cases of gear and food are packed onto the ship by Captain Tim and Brian Lariviere, the ship’s boat engineer. I’m particularly excited to see some familiar faces when we arrive at the dock — Jeff Miller and Lee Richter from the South Florida/Caribbean Network (SFCN) are here! Jeff, Lee, and I worked together during my first internship project in St. Croix, USVI. We catch up with each other and I meet their co-workers, marine biologist Rob Waara and intern Brandy Arnette. The SFCN crew will be conducting benthic reef surveys and staying on Loggerhead Key, the largest island in the park. There are only two houses on the 49-acre island, both of which run solely off of solar power. The only other structures on the island are the Loggerhead Lighthouse and a small boathouse that’s literally split in half (i.e. unquestionably uninhabitable). It is the true epitome of a remote subtropical island paradise — or prison, if that’s not your thing.

From left to right: Lee, Cameron, Elizabeth, and Chase prepare a game of Settlers of Catan in the galley of the MV Fort Jeff. I wish I could say I won, but Lee crushed us all.

Five hours go by on the ship. After a game of Settlers of Catan and a valiant attempt to catch up on blog writing (followed by a much-needed nap), I get restless. I’m pacing and glancing out the windows when a low-lying, dark stretch of land slowly appears on the horizon. The closer we get, the more I’m able to make out the features of the fort — the iconic red bricks, two-tiered casemates on all six walls, cannons lining the top, and a surrounding moat (currently dysfunctional due to Hurricane Irma damage). In short, it is like nothing I have ever seen before. During the first half an hour of unloading gear and touring the living quarters, I get a familiar feeling — the simultaneous rush of excitement, confusion, curiosity, and anxiety. Culture shock at its finest. I wouldn’t have ever expected to get such a feeling from visiting a national park, but DRTO is truly a park unlike any other. Within 30 minutes, the overwhelm settles and I unpack in my temporary home, a renovated apartment on the second floor of the fort.

That tiny strip of black on the horizon? Welcome to Dry Tortugas National Park!

I thought my three boxes of food was a lot, but not compared to how much food is required to feed Brett’s family of four with two teenage boys!

As soon as I finish unpacking, I hear a knock on the door. “If you’re free, could you take some photos for us?” Lead park ranger Curtis Hall explains that he’s helping with Coral Camp, a youth program for aspiring marine scientists. He would love some photos of the camp experience and has heard through the grapevine that I’ve come with a decent camera setup. I’m stoked at the chance to explore, so I grab my camera bag and meet the group at the dock to head over to Loggerhead Key. I spend the next few hours photographing the campers as they learn how to track turtles and identify nests on the beach, snorkel the reefs, and explore the island. It’s my first time using the SRC’s underwater camera rig, and while I’m happy with my topside shots, the underwater shots are whacky. Instead of filling out the entire frame, the photos are small and circular. I can’t figure out what the cause of the peculiar framing is, but I try to work around it. When I get back to Garden Key in the evening and mention the issue to Brett, he quickly identifies the problem. Of the two lenses I have for the Nikon D800, I used the shorter of the two, which isn’t long enough to fill out the underwater camera housing. A rookie mistake, but I’m learning. I’m thankful to have Brett around as I get comfortable with the new camera.

The Loggerhead Lighthouse was built in 1858 to aid vessels navigating through the shallow waters around Loggerhead Key and Garden Key.

Sometimes the best way to learn is to just be thrown in. Curtis was eager to get a photo of the entire Coral Camp group underwater, but with a new-to-me camera setup and novice photography skills, it was much harder than I anticipated. Determined to produce a decent final product, I compromised and had half of the group sit on the wall of the fort’s moat. While I didn’t get any spectacular shots, it was a useful chance to improve my split shot skills.

Loggerhead Key: An isolated island paradise.

This is what happens when you don’t use the right lens in your underwater camera housing!

—

What I’m really looking forward to is diving with the coral response team, but I learn upon arrival that I won’t be able to for at least a few days. Due to the combination of Covid-related housing rules and a recently damaged bathroom in one of the apartments, there’s a housing shortage on DRTO. Most of the biotechs are staying in Key West until there’s available park housing. Since the coral response team isn’t diving and I’m itching to get in the water, I convince the SFCN crew to let me join them on their survey dives for the next couple of days. Dad jokes and one-liners quickly recommence once I’m back on the boat with Jeff and Lee. Paired with Rob’s entertaining DJ skills and Brandy’s easygoing sense of humor, it’s a fun time on the water with this group. Plus, they have snacks galore on the boat. Cheese balls and cheesy jokes?! The SFCN crew knows how to speak my language.

Rob Waara dances and wears shirts inside out like no one is watching.

This is what I get for accidentally leaving my rash guard on SFCN’s boat… I didn’t believe it when Jeff told me he got it on (apparently it took three people). Can’t argue with that photographic proof, though!

As mentioned earlier, SFCN is completing benthic surveys of the DRTO reefs. They’ve been monitoring and surveying these reefs for decades, so there’s a well-established protocol in place. The surveying process involves two teams — a setup team to prepare each site and a survey team to collect and record data. I’m jumping in with the setup team, Lee and Brandy. Our tasks are seemingly straightforward: descend on a site, find the site’s metal transect pins that are nailed into the benthic substrate, and run transect tapes from one pin to another. Once we’ve laid out all of the transects, Jeff and Rob will conduct the surveys and record data.

Brandy and Lee finish running transect tapes across a survey site.

Finding the pins is the real challenge. We have laminated photographs with notes about each site, including the distances between pins and the compass bearings from the origin pin (placed in the center of the site) to the others. Sometimes the photographs include a distinct feature that leads us straight to the pin. Other times, the photos aren’t so helpful and we spend minutes swimming back and forth over the reef until someone waves or yells (Lee’s rebreather hoses channel sound quite effectively, so it’s easy to hear when he’s found a pin). Once we spot the pins, we roll out the transect tapes. At some sites, Lee replaces old Hobo data loggers — small submersible devices that collect water temperature data. From this data, researchers can assess the frequency of water temperature trends, particularly warm and cold water events suspected to cause stress to coral reef ecosystems. We make fairly quick work of the sites, although a lightning storm rolls through, forcing us to quickly head back to Loggerhead and hide out while it passes. All in a day’s work here at DRTO!

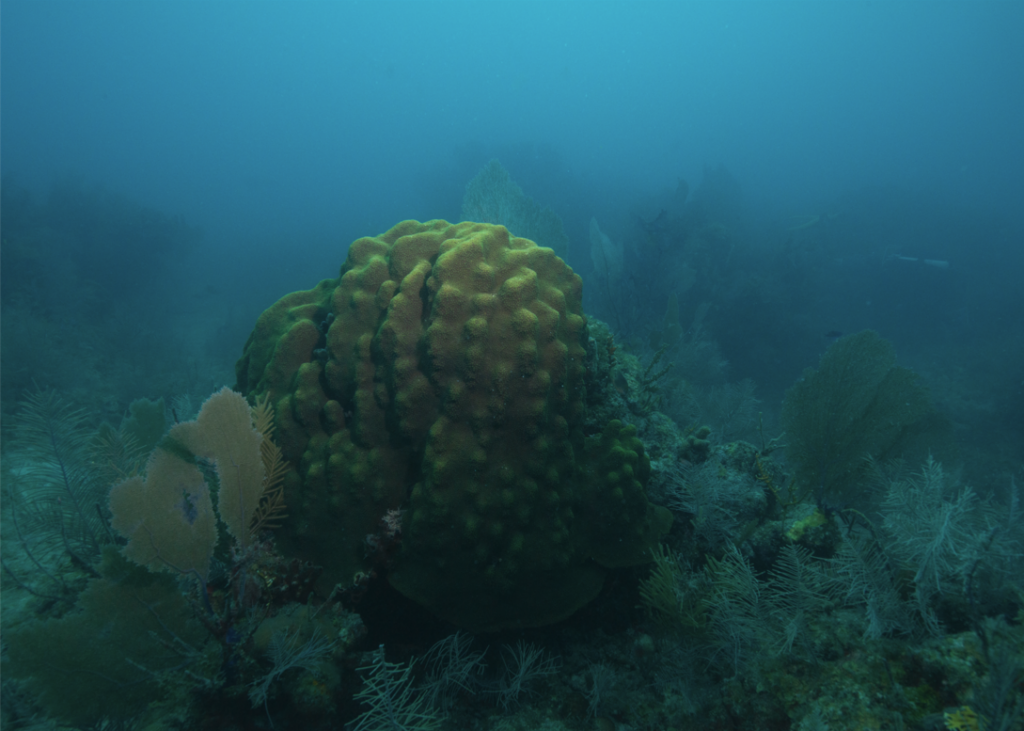

The DRTO reefs are some of the healthier aggregate reefs I’ve seen in a while.

Lee uses photos and notes to determine which direction will lead him to the next transect pin.

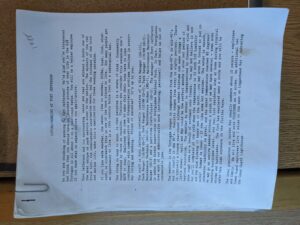

After finishing our survey sites for the day, Jeff takes us on another dive to see something special: this massive Orbicella colony.

Jeff measures the diameter of the Orbicella colony. After consulting with another coral expert, he tells me that this colony is at least 200 years old. “This is what we need to protect,” he emphasizes.

Jeff and Brandy inspect the Orbicella colony.

Jeff points to a SCTLD lesion on a much smaller coral right next to the huge Orbicella colony. This will become a high-priority site for the coral response team. If they can treat the lesions, they may be able to prevent further spread of the disease onto any neighboring corals.

—

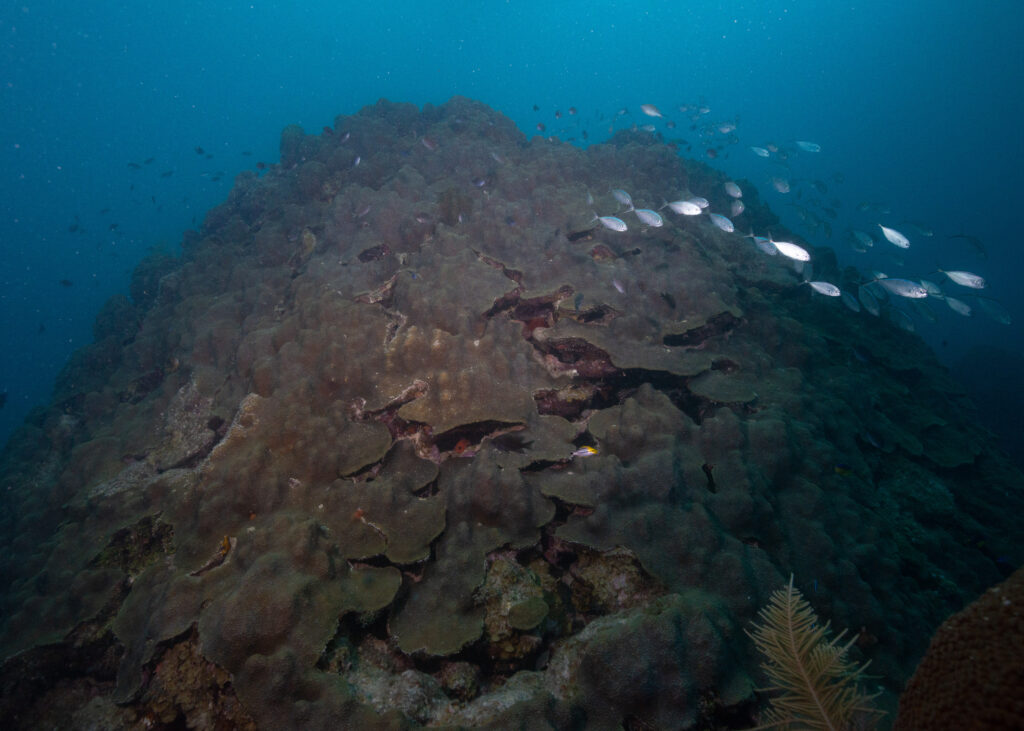

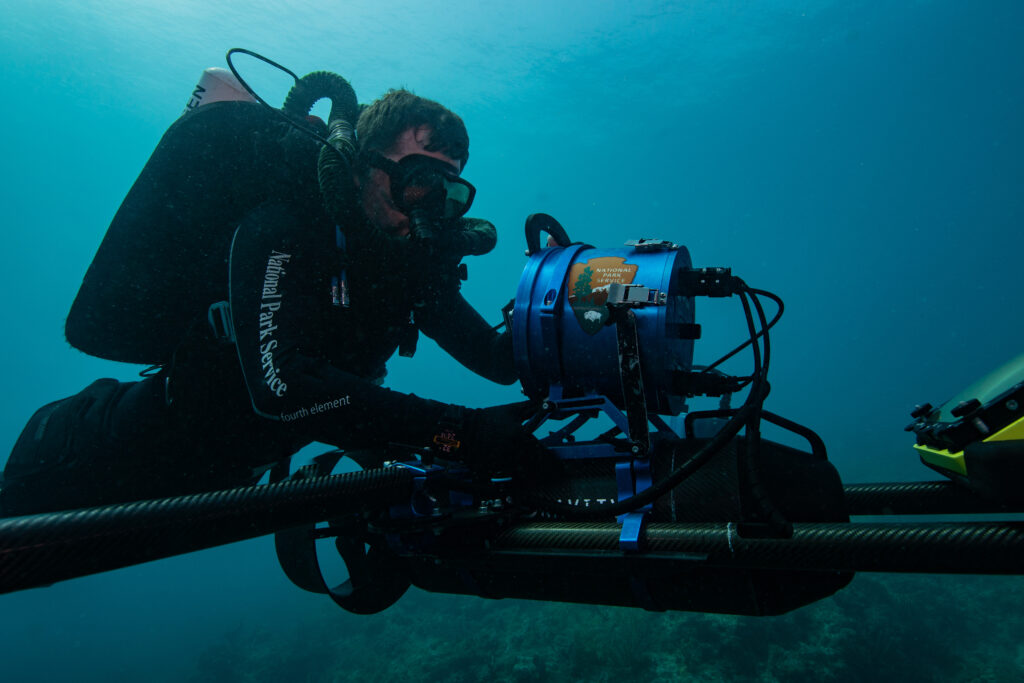

The SFCN crew drops me off at Garden Key at the end of the day and I eat dinner with Brett, his family, and Jim. While I’ve been diving with the SFCN crew the last couple of days, Brett and Jim have stayed busy surveying the DRTO reefs the “techy” way: with a high-resolution underwater camera system called the Sea Array. The large contraption consists of three cameras, a propulsion system, control panel, and sub-sea GPS navigation system. Essentially, the Sea Array uses photogrammetry technology to merge tens of thousands of digital images into a 3D visualization of underwater resources, like shipwrecks or coral reefs (if you’re interested in learning more about how the Sea Array, I encourage you to check out this engaging storymap). I’m eager to see the Sea Array in action and to continue working on underwater photography, so I ask to join Brett and Jim on the SRC’s boat, Cal Cummings, for a day. They agree, but they warn me that I’ll only be able to dive for about 45 minutes. Once the Sea Array is calibrated and ready to go, Brett and Jim use diver propulsion vehicles (DPVs) to cruise over the reef and complete their surveys. I’m a decent swimmer, but there’s no way I can keep up with them once the DPVs are turned on. On top of that, they use closed-circuit rebreathers, which allow them to dive for hours at a time — much longer than I could dive on my open-circuit system.

Brett Seymour operates the Sea Array.

Nevertheless, I meet them the next morning and we boat out to one of the reef sites that still needs to be mapped. Brian, the MV Fort Jeff’s boat engineer, is captaining for us. He’s an expert boatman — he can fix an engine in a pinch, and his boats are as organized as a Michelin star chef’s kitchen. “Everything has a place,” he reminds me as he neatly tucks my scuba gear into a corner — a much better spot than the middle of the boat deck. Mise en place – everything in its place — is especially important on the boat today, seeing as the Sea Array alone takes up a third of the boat deck. Along with it are three large buoys that we place on the outskirts of the survey site. The buoys use GPS to track the Sea Array while underwater and relay location information to the Sea Array operator and the boat. We drop the buoys, carefully lower the Sea Array into the water, and make our way to a sandy patch on the seafloor where Jim and Brett set up. I start snapping away on the camera, and once the Sea Array is ready to go, Brett cruises over the reef a few times so I can take more photos. I’m trying to be better about taking lots of photos during these moments. “If there’s space on the SD card, why not use it?” Multiple photographers have reiterated this to me. It feels indulgent to hold the shutter button down and hear the click, click, click continue on, but you never know what exact moment will give you “the shot”.

It’s difficult to convey just how large the Sea Array is.

Brett and Jim prepare the Sea Array for a reef survey. It’s not a quick task by any means — one site survey can take between three and four hours.

As the Sea Array cruises over this coral reef, it is capturing tens of thousands of images of the sea floor, which are compiled to create a highly detailed 3D map of the reef in its current state.

—

On my last day, the coral response team makes it back to the park, and they’re ready to dive. I’m bummed to be leaving right after they arrive, but one day is still plenty of time to treat some corals. I’m spending the day with Karli Hollister, Rachel Johns, and Clayton Pollock. They have a priority list of sites that need SCTLD treatment. Tackling the disease is difficult due to its rapidly spreading nature, but by isolating diseased colonies there is a chance to halt disease progression. To do so, we use a mix of amoxicillin and Coral Cure Base2b, a specialized paste designed to adhere to coral. Rachel, a coral biologist and lead of the coral response team, shows me how to mix the paste and explains the application procedure. The Base2b paste adheres to coral skeletons, not living tissue. For it to adhere effectively, it must be applied directly to the lesion lines where the disease has already killed the coral’s tissue. Then, the amoxicillin antibiotic is slowly released into the coral.

An up-close shot of the antibiotic paste used to treat SCTLD. The white section is skeleton, but the top portion of the coral is still alive and could potentially be saved.

Karli Hollister (left) and Rachel Johns (right) work together to treat the lesions of a coral infected with Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease.

The antibiotic paste must be worked into the lesion line where the already killed coral and healthy coral meet. When applied well, the paste can isolate the diseased portion from the healthy bit.

Karli Hollister treats an infected coral.

—-

By the end of my stay in DRTO, I’ve had the lucky opportunity to work with not one, but three different dive teams while in the park. Individually, each team has their own focus — from novel and large-scale photogrammetry efforts, to continued long-term reef surveying and monitoring, to targeted coral intervention and disease treatment. Collectively, however, each project shares the same overarching goal: to understand, preserve, and protect the valuable and unique underwater gardens of Dry Tortugas National Park.

In the 1850s, a ship filled with barrels of powder cement sank off of Loggerhead Key. As the wooden barrels degraded, the cement was activated by the water exposure and set in place underwater. You can snorkel and see dozens of these cement “barrels” in rows, the same formation they were on the ship.

A lush thicket of Acropora prolifera totally blew me away during my DRTO snorkeling adventures. So healthy, and so much of it!

Whether you’re diving deep or snorkeling in the shallows of DRTO, there is always something interesting to see.

Dry Tortugas isn’t the easiest place to live, but everyone (and everything!) there seems to find a way to be resourceful and thrive.

If I wrote about all the memorable moments I’ve had in Dry Tortugas, this post would easily become twice as long. So many people helped to make this an unforgettable experience. As always, a huge thank you to OWUSS and the SRC for making this trip possible. To the entire staff at DRTO — your dedication and passion are positively infectious. Thank you for making me feel welcome and sharing your work, stories, and time with me. I hope to see you all again one day! SFCN crew — thanks for the laughs, the snacks, and for making me feel like a part of your team once again. Always an honor to be on a boat with you fine folks. And to Brett, Elizabeth, and Jim — thank you for being exceedingly willing to feed me, help me, and go out of your way to maximize my opportunities during my internship. It has been a privilege to spend the last 10 days in such an incredible place with such wonderful people.

My last Dry Tortugas sunset — for now!

Good blog, interesting blog about important conservation work in a fascinating place, thanks. Good images, great to see Elizabeth and boys, crew and Sea Array work shots. Hope the coral treatment works.

Nice work!