I was bushwhacking through the Hawaiian jungle, clothes still wet from the day before. The sweet yet pungent smell of fermenting guava permeated the humid air, and my boots squished as I stepped on one of the overly ripe yellow fruits littered on the ground. As I trudged, I looked closely at the overgrown trees and bushes, occasionally plucking a white ginger flower and sucking the sweet nectar from its stem. Slowly, the sound of running water grew louder and louder. We were almost there.

It was my second week in Kalaupapa National Historical Park, and I was taking a break from dive operations and marine surveys. This week, I was helping the NPS Inventory & Monitoring (I&M) Pacific Island Network (PACN) with freshwater stream surveys in the steep forested Waikolu Valley. I&M has monitored Waikolu Valley’s water quality and freshwater habitats since 2006. Freshwater ecosystems are quite vulnerable to anthropogenic impacts (eg. land-use change, invasive species, eutrophication (i.e. excessive nutrient richness), and temperature changes). Collecting data provides insight into long-term trends in water nutrient levels and population dynamics of freshwater fish and invertebrates, some of which are endemic species that cannot be found anywhere else in the world.

A view into Waikolu Valley from the mouth of the stream, where freshwater meets the ocean.

The opportunity to work with the I&M crew for a week meant trading out my fins for hiking boots and my Halcyon BC for a Kelty 50 liter pack. We were heading into the backcountry. I looked forward to the opportunity to see Kalaupapa from a different perspective. I didn’t have much idea of what to expect for the week, but I knew that I was in good hands. Glauco, the Biological Science Technician at Kalaupapa, also works with the I&M crew and had done the Waikolu Valley surveys many times before. Joining us was Anne Farahi, the Lead Aquatic Biological Science Technician, and two additional I&M technicians, John Benner and Esaac Mazengia.

Glauco, Anne, and Esaac work on packing and prepping equipment in the office. With the unpredictable weather in Waikolu Valley, waterproof bags and sealed plastic crates are essential to keep things dry.

Rather than packing all of our gear, food, and surveying equipment out to our campsite, we had most of our belongings dropped off via helicopter. Kalaupapa NHP occasionally uses helicopters to complete park operations, and this week, they were used for gear drop off and to remove several massive super sacks of marine debris from one of the park’s beaches. On the first day of the project, Glauco and I hiked down to the beach with the debris and waited for the chopper to meet us. When it approached, Glauco caught the strap hanging from the chopper and secured a sack. Within seconds, the chopper lifted the sack and flew away to the other side of the peninsula. After a few repetitions, the beach was finally waste-free. Afterward, the rest of our crew — Anne, Esaac, and John — met us and we began the trek across the rock and pebble-dominated beach to our campsite at the mouth of the Waikolu Valley.

Glauco, dressed in bright yellow to make him more visible for the helicopter pilot, watches the chopper fly in to pick up the large white super sacks of marine debris.

After heli-ops, we set out on our hike across the very rocky beach to Waikolu Valley. I only faceplanted once!

—

The next morning, I awoke to the rhythmic sounds of waves crashing ashore and the slow trickle of sunlight into the valley. My 40-degree sleeping bag was plenty to keep me comfortable overnight, and I relished the warm air as I rolled out of my tent — a much more enjoyable experience than waking up shivering in the Colorado mountains (the backpacking experience I’m used to). I emerged from my tent and began my morning routine: breakfast, packing my daypack (and shaking the ants off of it), and getting dressed for a day in the forest and streams. By 8 a.m., we started our hike up into the valley.

Our gorgeous campsite at the mouth of Waikolu Valley. In the mornings and evenings, we’d watch as wild goats played on the red cliffs.

The hikes to our survey sites were the epitome of bushwhacking

I already knew that Kalaupapa was rich with living resources. In the settlement, there were banana and mango trees on practically every corner. The sweetest, juiciest oranges could be plucked from trees on the outskirts of town, and on the avocado trees were some of the largest Haas avocados I had ever seen. On top of that, Kelly had shown me how to process coconuts to collect their meat and milk, and Glauco had shared his freshly caught venison with me during my first week in the settlement. Still, as we hiked through the Waikolu backcountry, Glauco and Anne opened my eyes to even more that Kalaupapa had to offer. Red ginger plants lined the trail and produced a fragrant, soapy liquid when their pinecone-shaped bulbs were squeezed — a perfect alternative for hand soap or shampoo in the Hawaiian backcountry. White ginger quickly became my favorite, as it reminded me of the honeysuckle bushes in my childhood neighborhood. The ginger roots, scuffed down to the yellow by wild pig and goat hooves and our own boots, peeked out of the ground as we walked through the forest. It seemed like everywhere I turned, there was something edible to be found. Coffee plants, guava and strawberry guava, taro, kukui nuts, bamboo, tea plants — they were all growing happily in the forest.

John (left) and Esaac (right) try a Jamaican vervain flower. They really do taste like shiitake mushrooms!

The smell of fermenting guava will forever be ingrained in my sensory memory. It was great to pull one off a tree for a midday snack, though.

Glauco passes by an ancient mango tree alongside the trail.

Anne had done enough surveys in Waikolu to know each survey site by sight, and Glauco had a GPS to use for secondary confirmation that we were surveying the correct spots. Since I had never been in the Waikolu Valley before, I never really knew exactly where we were going or how long it would take to get there. In the mornings, the unawareness was nice — the hikes felt exciting and exploratory. Once we reached a survey site, the five of us would drop our bags on the side of the stream and get to work. We had a number of surveys to do at each site. Some were to assess water conditions, such as nutrient levels and streamflow. Other surveys involved assessing the Hihiwai population — Hawaiian freshwater stream snails.

Glauco (left) and Esaac (right) use a FlowTracker to measure the water velocity of the stream. The FlowTracker is a highly precise tool that requires careful handling and lots of focus.

The lives that these tiny freshwater snails live are remarkable. Eggs about the size of sesame seeds are deposited by adult snails onto the sides of rocks in the freshwater stream, where they remain until they hatch. Once hatched, the larvae are quickly washed downstream and into the open ocean. Months go by as the larvae grow, and after about a year the young snails begin the pilgrimage of a lifetime — a march, in single file order, upstream and back into the valley. Their strong muscular foot allows them to cling to rocks and withstand the force of waterfalls as they move into the current of the stream.

At each survey site, we would stretch a transect tape 30 meters downstream. Then, we would conduct surveys at certain points along the site transect.

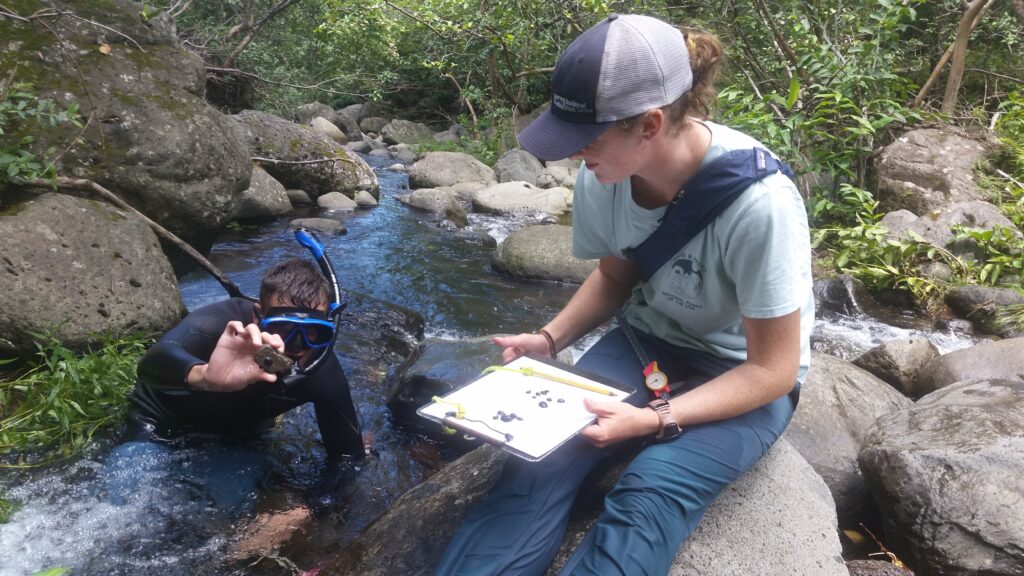

John (left) and I conduct snail counts and measurements. John would hold a small square quadrat down on the stream bed and remove any snails he found in the quadrat. Then, I would measure each one and record the data. The trickiest part was placing the snails back in the stream. If they weren’t secured properly, the rushing water would quickly flip them over, leaving them susceptible to crayfish predation.

John conducts a pebble measuring assessment. Sometimes we were measuring large boulders or bedrock instead, as pictured here.

In addition to the snail population, we surveyed the freshwater fish populations at each site. In Hawaii, there are only five native species of freshwater fish. All five species are gobies — adorable little fish with huge upward-pointing eyes that spend most of their time resting on the bottom of the stream and looking for food. Between the fish, snails, and the crayfish that also called the stream home, there was a lot going on in such a relatively small amount of water.

John holds a crayfish from the stream. These guys were curious — they loved climbing on our shoes or nibbling at our hands while we were working in the stream.

After each day of site surveys, we would pack up around 16:30 and trek back down to the mouth of the valley. As magical and enchanting as the morning hikes were, the afternoon hikes back to camp often made me feel like I was a character in Jumanji, trapped in the jungle and trying to find my way out. Mostly, I was just ready for dinner. Before I knew it, though, we’d get back to the campsite just in time to watch the sky turn pink and orange as the sun went down. And of course, dinner was always fantastic.

Anne works her way through a very overgrown section of trail.

I’m not sure how a car got so far up into the valley — needless to say, it never got back out.

Jurassic Park vibes, anyone?

When it rains, beautiful waterfalls pop up all over the steep sides of the valley.

Sunset views from camp.

—

The end of the week brought mixed feelings. I would’ve loved to stay at the campsite for a few more days — it truly was one of the best spots I had ever camped. At the same time, I desperately longed to put on dry clothes and shoes. Thankfully, the crew’s collective energy helped me push through the last day of surveys. After checking off four more sites, we packed our bags and trekked back across the beach. All in all, the week of surveys was a success. A huge thank you to Anne Farahi for leading our crew and sharing her immense knowledge of Hawaiian aquatic ecosystems with me. To John and Esaac — thanks for sharing your snacks (I’m a Belvita convert now), keeping the jokes flowing, and being awesome crewmates. Glauco — your venison mac n’ cheese is one of the best camp dinners I’ve ever had. Thank you for showing me all the incredible resources of Kalaupapa and for keeping crew morale high with great food and evening card games. Great crews make for great field projects, and I was lucky to be able to work with such fine folks during the week in Waikolu.

Packing out after the end of a successful week of surveys. Falling rocks were a hazard as we crossed the beach, hence the hard hats.

Gotta end things with a crew selfie!