Eight Navy battleships sat in Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, their captains and crew members unaware of what was to come early that Sunday morning. The men aboard started the day as they always did – with breakfast, morning duties, maybe a shower and a shave. Perhaps they were preparing for church service. Little did they know that a Japanese strike force consisting of 353 aircraft and 61 ships was headed to the harbor to launch a surprise attack that would become one of the deadliest events in U.S. history. Little did they know that many of them would die that day.

The Pearl Harbor attack killed 2,403 U.S. citizens and wounded nearly 1,200 more in the span of a mere hour and 15 minutes. Of the eight Navy battleships anchored in the harbor, four of them sank – all were damaged. The USS Arizona was the most irreparably damaged ship out of the fleet, exploding violently after being hit by Japanese torpedo bombers. When the ship exploded and sank, over 1,000 crewmen and officers were pulled down to their watery graves with her.

The 608-foot-long USS Arizona battleship remains sunken in Pearl Harbor. In 1962, the USS Arizona Memorial was constructed over the hull of the sunken ship and dedicated by the Pacific War Memorial Commission. The site serves as a national historic landmark, a poignant memorial, and a place for education and introspection. The National Park Service (NPS) operates the Pearl Harbor National Memorial (PERL), working in conjunction with the U.S. Navy to preserve and interpret the historical and cultural resources that are associated with Pearl Harbor and the December 7th, 1941 attack. To cap off an already incredible summer and internship experience, I headed to my last destination — Pearl Harbor — to experience the park and dive the USS Arizona wreck.

As I stepped aboard the small Cessna 208 that would fly me from Kalaupapa National Historical Park to Honolulu, I tried to prepare for the shift I knew I would inevitably face once I landed. I had grown somewhat accustomed to the remoteness and quietness of the Kalaupapa settlement. I hadn’t driven a car over 30 mph for a month and a half, let alone experienced traffic or a busy restaurant. I was very much looking forward to being back in the city, but it’s momentarily jarring to go from a remote place with limited resources to a bustling city with anything your heart may desire. Dan Brown, my PERL point-of-contact, had already anticipated this fact when he picked me up from the Honolulu airport. With keen interest, he asked me about my previous internship destinations as we drove to a Starbucks for breakfast. We chatted jovially until we walked into the coffee shop and I fell silent, staring in overwhelm at the display case and drink menu. It was going to take me a minute to get used to having diverse food options again.

Kelly Moore, the park dive officer at Kalaupapa, made me a beautiful fresh lei before I took off for Honolulu. Thank you, Kelly!

Caffeinated, fed, and eager for what the day would bring, Dan and I drove to the NPS dive locker at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam. The plan was to dive the USS Arizona that morning and switch out the two buoys that mark the bow and stern of the shipwreck. We were in a bit of a time crunch (Dan had afternoon obligations), so after chatting with Scott Pawlowski, PERL Museum Curator, we quickly put our equipment together and headed to the park visitor center.

A Navy-operated boat shuttle takes visitors to and from the USS Arizona Memorial every 15 minutes for most of the day, but Dan and I were lucky to hop on the last boat before the Navy crew went on a lunch break. As we stepped onto the memorial, the last batch of visitors departed on the boat shuttle. For 45 minutes or so, we had the space to ourselves. I was mentally prepared to artfully dodge visitors while quietly snapping photographs in the background — still a great opportunity, but not quite the same as being there alone. Having the site practically to myself meant that I could take my time experiencing the memorial, paying my respects, and doing my best to capture its symbolic architecture and historical significance. I was extremely grateful for the stroke of luck.

Dan and I got top-notch service on the empty boat shuttle out to the USS Arizona Memorial.

We walked into the USS Arizona Memorial’s entry room and stillness struck me. Despite a steady breeze gradually picking up from the northeast, the air felt calm and quiet. With no other visitors on site, it was practically silent. I stepped lightly, moving slowly across the memorial. The natural flow of the space leads visitors from the entry room to the assembly hall – the main open-air section of the memorial. The memorial’s architect, Alfred Preis, subtly incorporated a number of symbolic features into the structure’s design, particularly in the assembly hall. Seven large “windows” run along each side of the room, a nod to the date of the Pearl Harbor attacks – December 7th. Seven more windows are cut into the assembly hall ceiling to make a total of 21 windows, representative of the customary 21-gun military salute.

An American flag flies over the USS Arizona shipwreck and memorial.

The memorial was built directly over the USS Arizona wreckage. On one side of the memorial is gun turret 3, one of the most visible protruding parts of the shipwreck. On the other side of the memorial, you can see the USS Missouri — one of the WWII-era battleships that is still seaworthy. Also visible are the large white mooring quays the run along the coast. These concrete quays were used to secure the battleships along Battleship Row when the December 7th attack occurred. Aside from the USS Arizona and USS Utah shipwrecks, the mooring quays are the only structures that remain from the Pearl Harbor attack.

The USS Missouri in the distance. The large white structures are the concrete mooring quays.

The mooring quay for the USS Arizona.

Memorial visitors can peer over the railing and see rusty remnants of the USS Arizona shipwreck protruding from the harbor water.

On the far end of the memorial is a rectangular, cut-out section of the floor, which allows visitors to look into the water below. The wreckage of the USS Arizona rests just under the surface. According to Dan, this feature of the memorial was created to give survivors of the Pearl Harbor attack an intimate space to connect with their fallen comrades. Many visitors drop flowers in the water as a way of paying their respects to those who remain entombed in the wreckage.

I found myself staring over the railing and into the water below for quite a while. I knew that before too long I would be in the water myself, on one of the most significant dives of my career so far.

The natural flow of the memorial leads you over the resting shipwreck and into the shrine room, home of the Remembrance Wall.

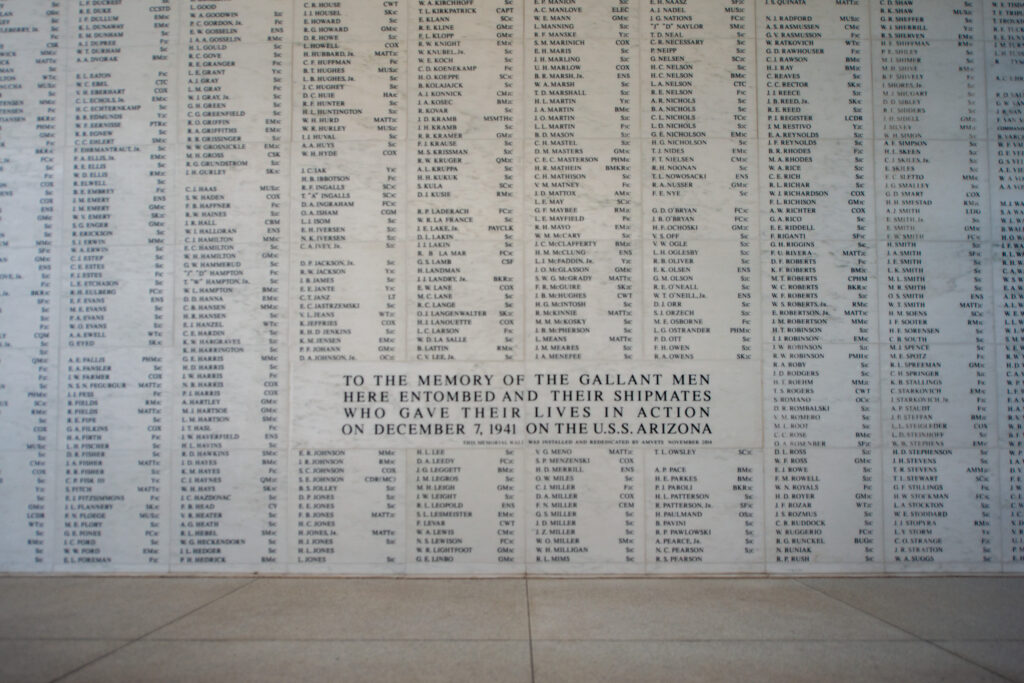

The shrine room, the last room of the memorial, quietly demands reflection and reverence. For in it is the Remembrance Wall — a marble wall with the engraved names of the 1,177 sailors and Marines killed on the USS Arizona. It is a collective headstone for all who passed when the ship sank. In addition, two marble placards in front of the wall are engraved with the names of USS Arizona survivors who have since been interred with their fallen comrades. Each year, on December 7th, the Navy and NPS conduct a memorial service and ceremonious internment of recently deceased USS Arizona survivors.

The Remembrance Wall is a headstone for brothers, husbands, sons, and friends. For many who have visited the memorial over the years, there is a particular name that sticks out amongst the towering columns of first initials, last names, and military ranks. That name is not just indicative of a man who died during the fall of the USS Arizona — it is the name of someone they shared life with, someone they had memories of. Someone they loved.

The Remembrance Wall. At the base of the stairs you can see the two placards that are continuously updated with the names of USS Ariona survivors who are interred with their fallen comrades.

1,177 men, lost in one day.

Memorial architect, Alfred Preis, designed the Tree of Life sculpture to inspire contemplation of life, loss, and renewal.

It’s difficult to see a number — 1,177 — and truly comprehend how many people that equates to. The Remembrance Wall helped me visualize the immense loss of life that took place on December 7th, 1941.

Dan Brown walks through the opposing doorway on the other side of the USS Arizona memorial. To have the memorial to ourselves for an hour was absolutely surreal.

I was captivated by the memorial, but there was even more to be experienced underwater. It was time to switch gears. I carefully placed my camera in its underwater housing and Dan and I began setting up our dive gear on the dock. We didn’t have a ton of time, so we made the decision to hold off on replacing the marker buoys. I think Dan sensed how much I wanted to focus on photographing the wreck, too. I appreciated how accommodating he was, especially when we jumped in, descended, and I realized that my strobes weren’t flashing. We popped back up to the dock and I performed the careful operation of opening the camera housing and fiddling with the strobe connection wire, my arms wrapped in towels so I wouldn’t drip a single bead of water into the housing. Once everything was sealed and operational, we jumped back in and slowly descended once again.

The diver down flag informed passing boats, memorial visitors, and tour guides that Dan and I were diving on the USS Arizona.

Visitors began to populate the memorial by the time Dan and I started our dive.

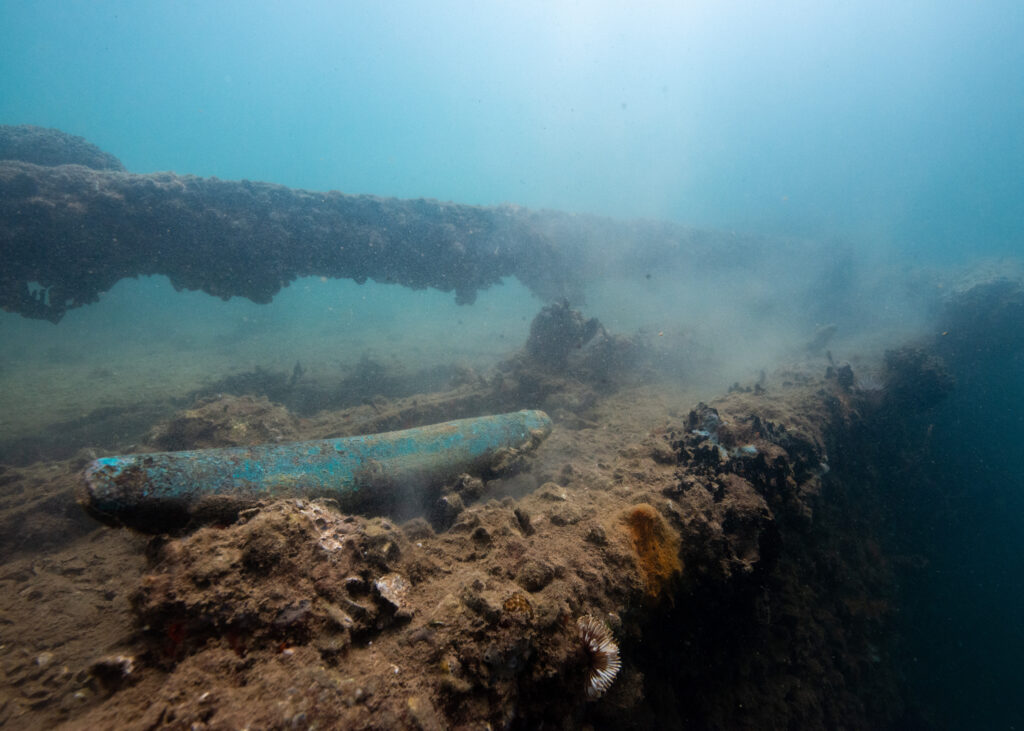

I had been told to expect low visibility for the dive, but I was pleasantly surprised to discover that I could, in fact, see further than my hand in the harbor’s murky green water. Dan led the way and I followed, stopping every few feet to take photos and process what I was looking at. I was diving on the USS Arizona shipwreck — something very few people have had the opportunity to do. I moved slower than I ever have on a dive, scanning every bit of the wreckage and looking for artifacts underneath the layers of algae and sediment.

In the same way that the NPS protects the hot springs and geysers in Yellowstone and the petrified wood in Petrified Forest National Park, the NPS closely monitors and protects the USS Arizona and the artifacts that remain on the wreck. It’s no easy feat — they are tasked with preserving, protecting, and interpreting this monumental collection of historical and cultural resources and leaving it unimpaired for future generations. The more time I spent in the park, the more I was impressed by how well the NPS has done just this. By preserving the USS Arizona and its associated artifacts, they have kept the story of Pearl Harbor alive.

One of the USS Arizona’s mooring cleats remains on the deck of the ship.

It was haunting to see old pitchers, bottles, and pots scattered across the deck of the wreck.

As I explored the wreckage, thoughts on the significance of sacrifice and the price of peace weighed heavily on my mind. I’ve been diving on shipwrecks before, but the USS Arizona is different. It isn’t just a shipwreck — it’s a mass grave. It is a physical touchstone of one the deadliest events to happen in U.S. history. Even more striking to me is the fact that the ship has been there, laying in the depths of Pearl Harbor, since 1941. My parents weren’t even alive by then. Pots from the ship’s galley lay untouched on the ship’s deck. Soda bottles. Shoe soles. Multiple staircases descend from the main deck into the depths of the wreck, railings still intact. As Dan and I explored it all, I distinctly remember noticing how quiet it was — hauntingly so. The reality of what I was exploring hit me when Dan pointed out the original teak decking of the USS Arizona, still clearly visible under a thin layer of sediment and debris. How many men were standing on this deck when Japanese torpedo bombers started firing from above?

The ship’s original teak decking.

Dan Brown writes notes as we pass over an encrusted cooking pot on the ship’s deck.

Slowly, we made our way around the perimeter of the ship and to the bow. Dan was a fantastic guide, stopping to show me artifacts and features of the ship. At one point, he pointed to a small stream of brown bubbles rising up from a hole in the ship. 80 years after sinking, the USS Arizona continues to slowly leak oil. Some refer to the patches of oil that leak from the ship as “black tears”.

If you look closely, you can see the brown tinge of the oily bubbles as they slowly ascend to the surface.

A glass bottle and debris intermixed with small patches of coral. The shipwreck acts as an artificial reef, providing corals with a substrate to grow on and serving as protective habitat for many fishes and marine creatures

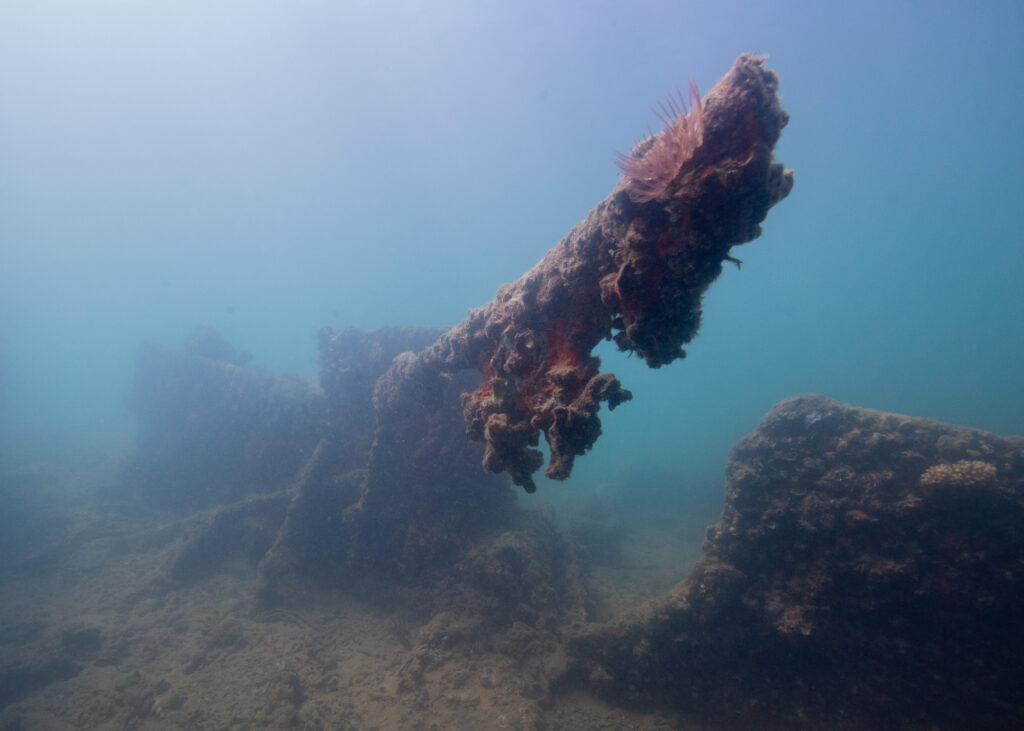

An anemone reaches out from the tip of the ship wreckage, filter-feeding in the water.

The end of an amazing dive is always bittersweet. On one hand, you don’t want to go back to the surface — you want to keep diving! On the other, the moment where everyone surfaces and can finally speak to each other is always exciting. Sometimes there’s so much to talk about, you don’t know where to start. Sometimes you’re at a loss for words, which is where I found myself as we climbed back onto the dock. Before we knew it, though, visitors were walking by and asking us what we were doing (“we’re going to be asked what we’re doing at least a dozen times”, Dan warned me earlier that morning). Talking to the memorial visitors knocked me out of my momentary speechlessness, and Dan and I remarked on the artifacts we noticed and the great visibility — “one of the top five dives I’ve done here,” Dan enthusiastically noted.

Dan Brown makes his way over the three 14-inch guns at the bow of the USS Arizona.

These guns are nearly 60 feet long — in low visibility, it’s nearly impossible to capture their grandiose presence.

A shift in perspective.

The following day was for topside exploring and seeing more of PERL. Dan and Scott Pawlowski invited me to come snorkeling with them on the north side of the island, an area I was eager to explore. One of my roommates, RB, was also new to Oahu and keen to join us. Dan picked us up mid-morning and we drove up the north shore to Three Tables beach, passing lush forests, food stands, and busy surf beaches along the way. We met Scott at the beach and chatted for a while before swimming out to the reef.

Beach views on the north shore of Oahu.

After the snorkeling excursion, RB and I drove to the PERL visitor center and picked up passes for the USS Missouri and the USS Arizona Memorial. RB hadn’t been to the memorial yet, and I wanted to get a few more shots while I had the chance. As much as I appreciated having the memorial to myself the other day, it was also a special experience to spend time there with other visitors.

From there, we took a shuttle bus to the USS Missouri. The highly decorated battleship is most well-known as the site of Japan’s surrender in World War II. Nowadays, the ship has been turned into a museum of sorts — every few feet, there are informational displays that tell the story of the USS Missouri. We spent a while on the ship, peering into the many rooms onboard and reading about the battleship’s extensive history.

Approaching the USS Missouri.

It was a good thing I had a wide angle lens with me. This ship is huge!

The USS Missouri — tour guide for scale.

On my last day in Hawaii, Scott and I met at the PERL visitor center for a tour of Ford Island and the PERL memorials that aren’t open for public access (Ford Island is still an active military base, hence the inaccessibility). Our first stop was the USS Utah Memorial. As I walked down the memorial’s white dock and looked at the vast landscape ahead, I couldn’t help but picture what the horizon must’ve looked like on that fateful day in 1941. Planes must’ve been flying overhead from every direction, relentlessly bombing whatever was below. In the case of the USS Utah, torpedoes struck the ship and caused it to quickly capsize. Most of the crew made it out alive, but 58 of the men onboard were killed in action.

The USS Utah lies next to Ford Island. 58 of the ship’s crewmen were killed when the battleship was torpedoed and sank.

The second-greatest loss of life at Pearl Harbor occurred on the USS Oklahoma, affectionally referred to as “the Okie” by its crewmembers. The USS Oklahoma sank quickly on December 7th, 1941 — less than 15 minutes after the first torpedo hit Battleship Row. Within minutes, hundreds of men found themselves trapped under the decks, flipping upside down as water rose all around them. 32 men were retrieved from the wreckage in the next two days. 429 of their comrades never made it out.

The USS Oklahoma Memorial was designed with the U.S. Navy’s tradition of “manning the rails” in mind. The rows of white granite columns stand tall, emblematic of when Navy crews line the ship railings in dress whites when they return to port. On each of the 429 columns is the name of a crewman who was lost with the USS Oklahoma.

Each granite column of the USS Oklahoma Memorial has the name of a crewman who was lost on the ship during the Pearl Harbor attack.

NPS routinely takes standardized photos of each column of the USS Oklahoma Memorial, which helps them monitor wear and tear and perform repairs when needed. Over the years, the granite can crack and degrade from the salty air and sunshine.

Every part of my PERL experience had its own respective impact. Photographing the USS Arizona Memorial and spending time in the shrine room helped me comprehend the mass loss of life that took place during the attack. Diving on the USS Arizona itself put the scale of the event into perspective. Viewing the other memorials gave me an appreciation for all the time, money, and effort that has gone into making PERL the educational and historic site that it is today. However, I don’t think I emotionally processed what happened at Pearl Harbor until I was in the depths of the museum collections building with Scott.

The museum collections building has rooms and rooms of artifacts, documents, and memorabilia that are related to Pearl Harbor and the 1941 attack.

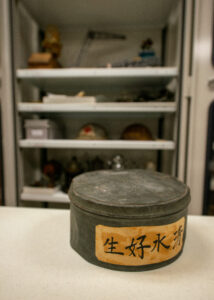

Being the museum curator, Scott knows the story behind practically every artifact in the collection and has even stayed in touch with many of the families and individuals who have donated items. We took our time in each room as he showed me WWII-era swords with handles made out of shark skin and combat medic hats, rusty but still intact. Every piece had a story, and oftentimes Scott could tell me about the individual who brought the item in, where it was from, and exactly how it was discovered.

Scott presents a WWII combat medic’s hat.

This Japanese hatbox belonged to a soldier who died in the Pearl Harbor attacks. Years later, his widow actually came to Pearl Harbor and was able to visit the collections building and see the hatbox for herself. Scott said there wasn’t a dry eye in the room that day.

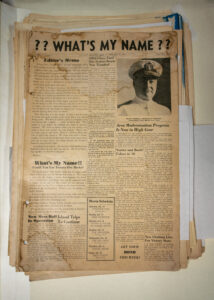

We continued to work our way into the collections, moving from larger artifacts to smaller items, like medals and papers. I could’ve easily spent hours sifting through the pages and pages of carefully preserved newspapers. Seeing the old pages and dates put into perspective just how suddenly the month of the Pearl Harbor attack went from a typical December to a month of immense loss, grief, and trauma for the entire United States.

I could’ve easily spent hours sifting through the pages and pages of old newspapers in the PERL museum collections building.

Carefully stored and preserved uniform pieces.

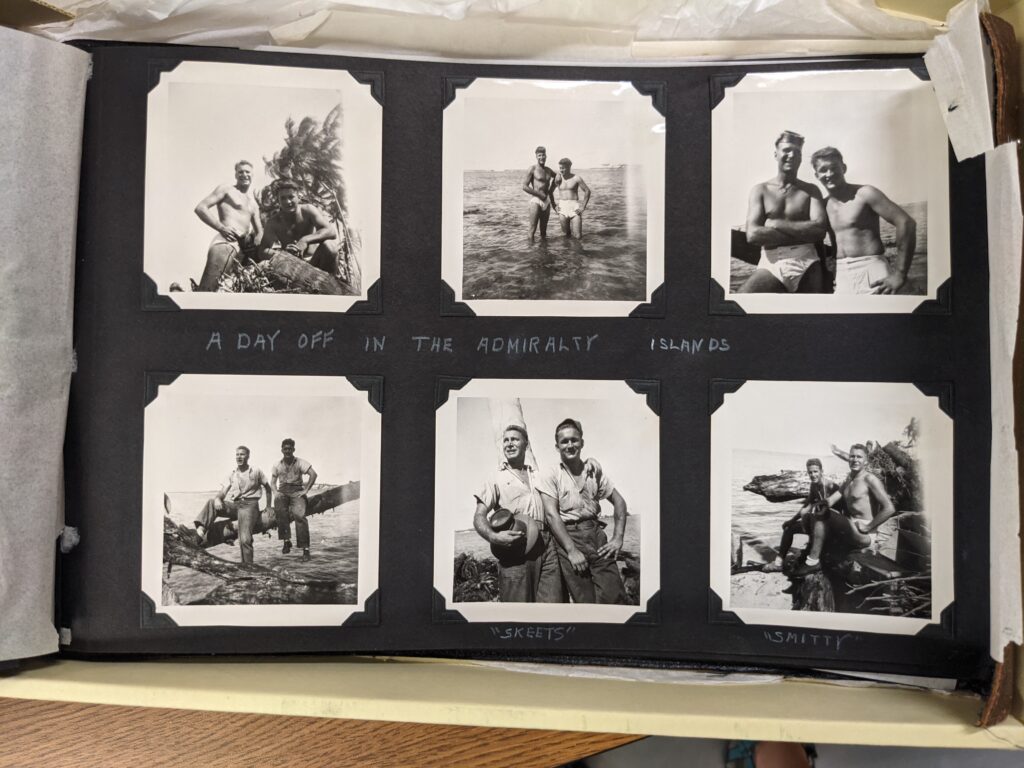

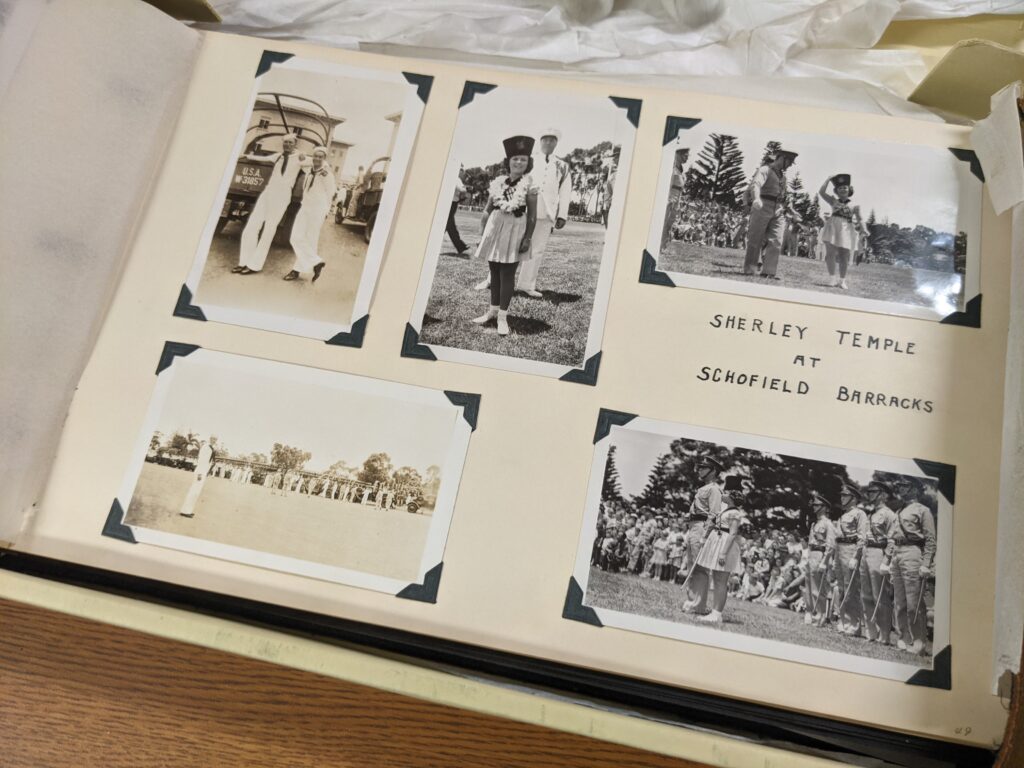

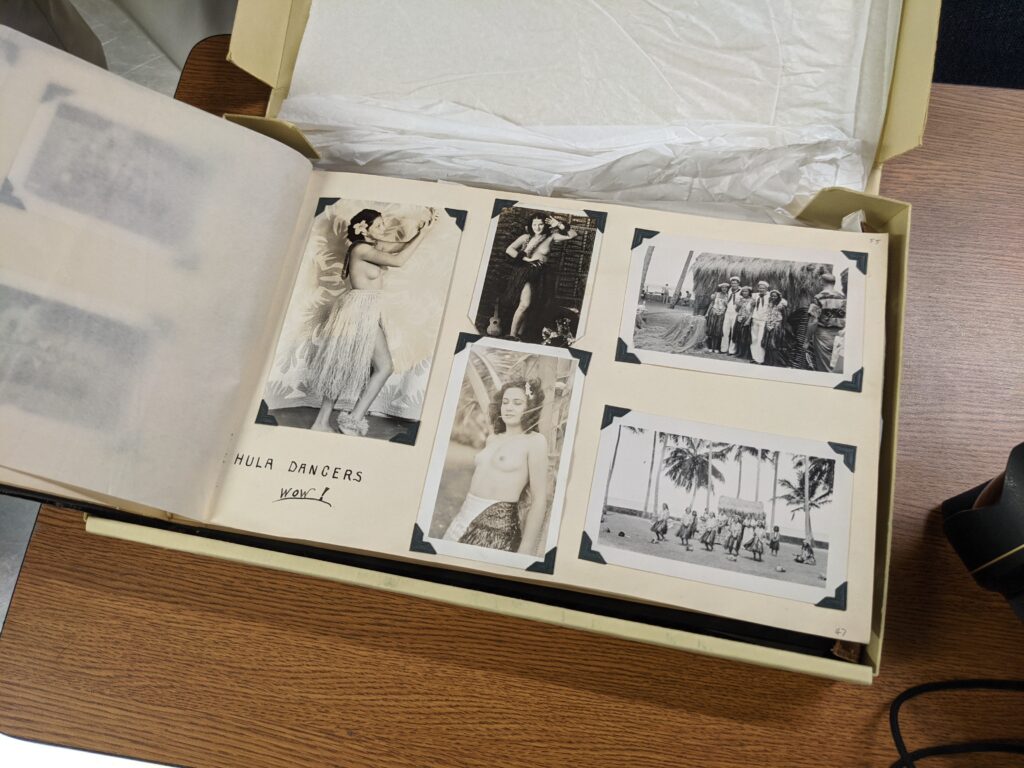

The last items Scott pulled out were old leather-bound photo albums, purchased by sailors when they arrived at new ports and filled with old photographs of their families, friends, and travels. As Scott carefully flipped through the pages with gloved hands, I was hit with a staggering wave of emotion. On December 7th, 1941, in less than two hours, the lives of so many men just like the ones in the photo albums ended. In a sudden and tragic moment of sacrifice, their lives became unfinished scrapbooks and uniforms that would never be worn again.

Walter F. Staff’s photo album from his time on the USS Oklahoma.

The sailors’ photo albums were filled with photos of their friends, families, and the new places they traveled to during their deployments.

Flipping through the pages of sailors’ photo albums provided insight into their travels and the memorable events they partook in along the way.

“Wow!”

Going to Pearl Harbor at the tail end of my internship and thinking about how precious life is – and how quickly it can be lost – reminded me just how important it is to embrace each day you get to live, especially if you’re lucky enough to spend those days doing what you love. I left Pearl Harbor feeling incredibly reflective and indescribably grateful to all those who made it possible for me to experience the national memorial in such an intimate way. A huge thank you to Dan Brown and Scott Pawlowski for generously sharing your time and showing me the historical and cultural resources of Pearl Harbor National Memorial. Thanks to Shaun Wolfe for finding me great accommodation while I was on Oahu, and to OWUSS and the NPS SRC team for providing unwavering support throughout my internship.

Lastly, thank you to those who have followed along with my journey and provided encouragement and kind words along the way — it has meant so much to me. If you’d like to read my final thoughts and reflections from my internship experience, keep an eye out for my final report. I hope you will continue to follow the journeys of future interns and support the efforts of OWUSS and NPS. There is no question that this experience has monumentally changed my life, in ways that I probably cannot comprehend quite yet. I look forward to taking what I have learned this summer and continuing to preserve, study, and document the incredible underwater resources of Earth’s oceans.