On May 13th, I began my journey as the 2023 American Academy of Underwater Science (AAUS) Mitchell Scientific Diving Research Intern for the Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society (OWUSS) by boarding a flight from New Hampshire to Miami with the final destination of the Keys Marine Lab in Layton, Florida. With only a handful of warm water dives under my belt—warm water to me is anything above 55 degrees Fahrenheit—Florida was definitely foreign territory for me.

I will spend my summer focusing on coral reef sponge ecology research with PhD candidate Bobbie Renfro of Florida State University and her team. Bobbie is studying the effects of nutrient pollution on the sponges that live on coral reefs. Sponges play many super important roles in coral reef ecosystems! Sponges act as a form of glue, holding all the reef together, preventing erosion and helping living corals stay attached to the reef. Without sponges, reefs would not be anywhere near as storm resistant as they are. Sponges also are the habitat for tons of coral reef critters like brittle stars and snapping shrimps. One of the most important roles of sponges on the reef is their ability to filter the water. Sponges are able to create a strong current throughout their canal systems that actively pumps dirty water in and clean water out—acting essentially as a Britta filter.

After I picked up my comically large number of bags, I met Bobbie and her other undergraduate assistant Sydney. We drove from the Miami airport down to Long Key, and I got to take my first look at where I will be staying for the next 8 weeks. I got to move into the “Bay House” which was located off to the side of the Keys Marine Lab Facility looking out over Florida Bay! But my first day was not over yet, we headed down to the dock—sunlight was far gone at this point—to finish a portion of Sydney’s thesis project. The extent of my involvement of this was mainly holding up light so Bobbie and Sydney could see what they were doing in the water below, but I was excited to get started right away.

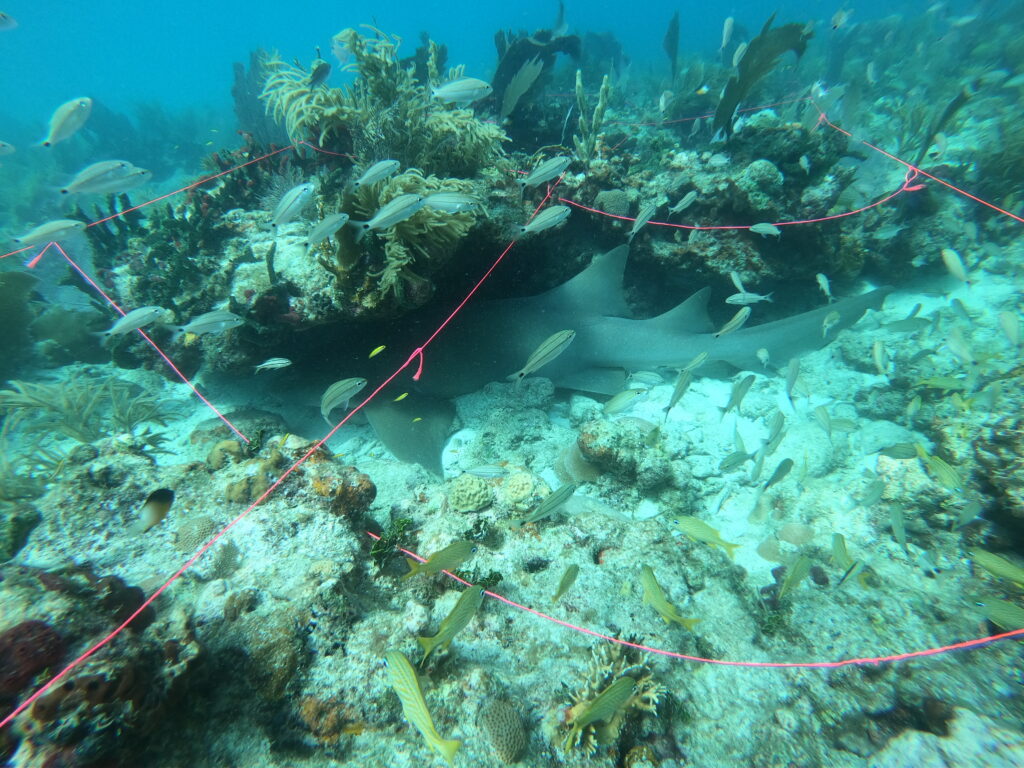

The day after was my first dive day in the Keys. I was very happy to shed my dry suit and 25-pound weight belt in exchange for a thin dive skin and 8 pounds. The water was almost double the temperature than back home for me! The majority of our dive work took place at one of our four coral reef sites, with half having poor water quality and the other half having good water quality to allow us to make explicit comparison of how nutrient pollution in the poor-quality water affected the sponge communities.

I completed four separate dives on my first day, mainly focusing on collecting samples for future projects. But not every day looked like this. We had a wide variety of projects we could be working on any given day.

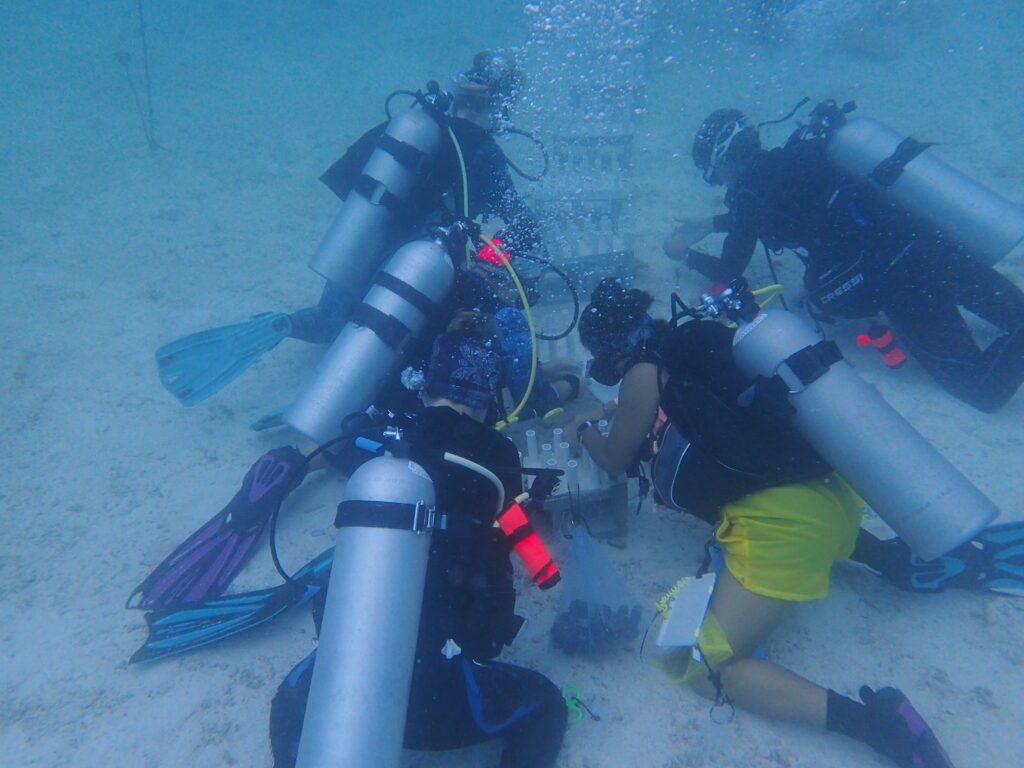

Feeding Trials

The most prominent project was the “Feeding Trials” where we essentially looked at the filtration rates of different sponge species at all four of our sites. These involved two divers in the water setting up incubation chambers. Sponges were placed into these chambers, then we would extract samples at various time increments. The third team member was topside receiving, sorting, and filtering the samples. Each feeding trial involved five sponge individuals and one control. Approximately six feeding trials were conducted at each of our four sites total. This produces a lot of water samples!

Sponge Survey

We also went on surveying dives where we measured certain sponge species within a permanently marked surveyors’ grid that Bobbie established at each site since 2019 and has surveyed annually since. How did we measure them? A lot of fancy underwater geometry.

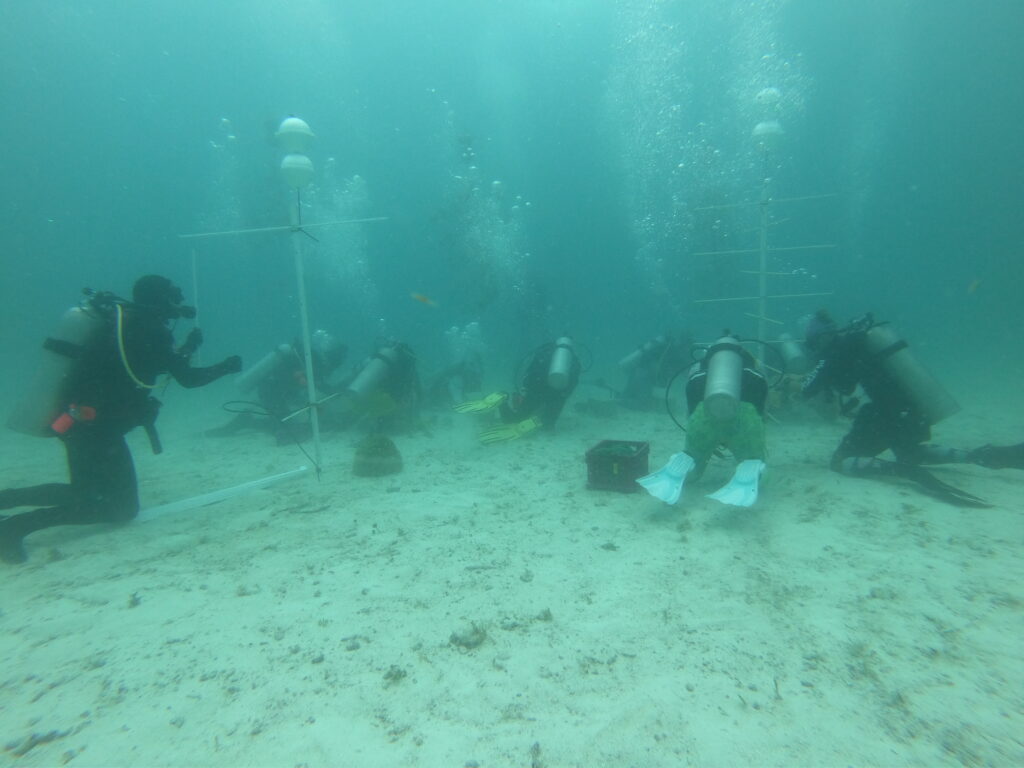

Sponge Restoration with I.CARE

Every Wednesday we got to work with our restoration partners at Islamorada Conservation and Restoration Education (I.CARE) and Key Dives to train recreational divers on sponge restoration. We head to the Key Dives shop early on Wednesdays where we would setup to give a presentation to recreational divers on everything you need to know about coral reefs and sponges! After the presentation, we gave a demonstration on the specific sponge transplantation techniques we would be using. After the demo, we would take the divers out to one of our restoration sites where they get to transplant sponges to the reef! We monitored the scientific integrity of the restoration work while I.CARE and Key Dives staff monitored the safety of the divers.

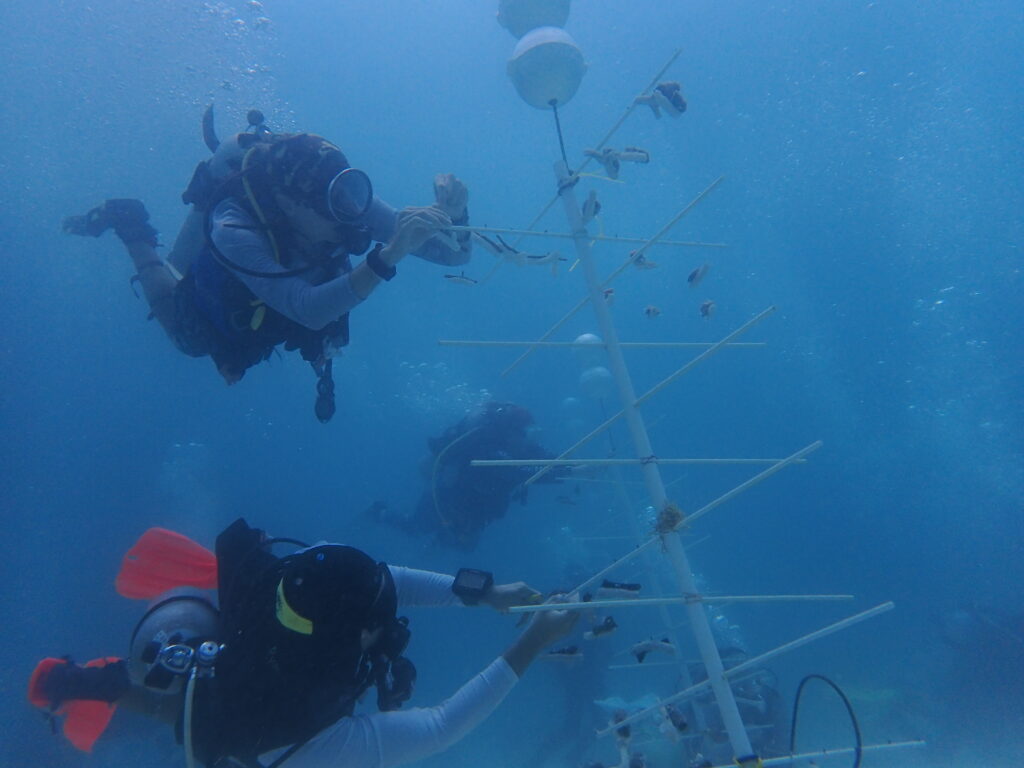

The First Coral Reef Sponge Nursery in the Florida Keys!

One of the most ambitious projects we worked on was the assemblage of the first coral reef sponge nursery! We worked with Mote Marine Laboratory to set up this nursery at Mote’s Coral Nursery in Islamorada, Florida. First off, to set up the nursery we needed to collect hundreds of sponge samples to adequately stock it.

The nursery setup took place in one day and involved approximately 15 divers total from Keys dives, ICARE and Mote Marine Lab.

This project had so many moving pieces and seeing it all come together was incredible! I can’t wait to see how much the sponges grow over the next six months – Bobbie will calculate their growth in December and send me an update!

Out of the water and into the lab

After we finished up our dive activities, we head back to the Keys Marine Lab to unload the boat and clean our dive gear. Once the boat is cleared, we head to the lab to start processing our samples. We almost always have a large number of water samples that need to be frozen—this often involves a decent bit of Tetris in the communal lab freezers. Just as the diving activities differ each day, so does the lab work. On feeding trial days, the lab activities often involved weighing and calculating displacement volume of the sponges used for trials. Periodically throughout our time in the keys we took chlorophyll samples. This involved us collecting approximately four liters of water from one of our sites and pushing them through a filter which we would save at the end to analyze its contents. The chlorophyl in the water comes from the photosynthetic plankton and can affect how much light reaches the sponges.

Once we finished lab work, the days not over yet! Once we got back to the Bay house, we often had to start the setup process for our dive projects the next day. The night before each feeding trial we had to collect all the tubes we would need the next day and label them all—we needed about 100 tubes total for one feeding trial. We also needed to make sure all the feeding trial containers, filters, syringes, and everything else was washed with DI water and ready to go. If we have ICARE restoration the next day, we would prep the sponges that were being out planted by attaching them to small pieces of coral rubble.

In total, in my 53 days in the keys I completed 72 scientific dives throughout the upper and middle Florida Keys. But my summer is not over yet! After a brief break, I am headed to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Bocas Del Toro, Panama for the second half of my internship. I look forward to sharing my research adventures from Panama!

What an unbelievable experience. Thanks for sharing it with us!

Excellent recap, Jack! Amazing how many dives you did in just 53 days. The photos really illustrate the work you all did. Bravo! We look forward to reading more from Panama. Cheers, Greg & Kim