My second week at Biscayne kicks off the derelict trap retrieval operation everyone at the office has been anticipating. This is the one week, every two years, that they can remove whatever lobster, stone crab, and blue crab traps they find. This is the only ten day period every two years during which blue crab season. For this week, and this week only, all three traps left in Biscayne National Park are illegal, because all three fishing seasons are closed. The team has been carefully recording the locations of traps for the last two years, and if they are still in place, they will know for sure that they are derelict, abandoned, or illegal.

Monday, we also conduct some turtle surveys, collect water samples for red tide, and remove any derelict traps we spot along the way. The bay is a smooth mirror and we can see everything from the boat, right down to a little nurse shark snuffling its way through the eelgrass. The water is so clear that when I jump in to grab two traps without buoys, I can see without a mask. Pulling up older traps is like pulling up a treasure chest. They are packed with lobsters, crabs, brittle stars, and translucent baby Caribbean octopuses with eyes like opals. Seriously. They are the most amazing glittering blue orbs in an otherwise colorless little slime ball of cuteness.

After a week of calm seas and skies, Mother Nature decided that this week of all weeks was the time to let loose. The forecast shows an onslaught of thunderstorms peppering Biscayne National Park all week. Luckily, being in Florida means it could be pouring buckets on you, but if you slung your dive buddy off the boat, they’d be under sunny skies. I’m not strong enough to throw them overboard with their steel cylinders (if you haven’t picked up by now, I have a grudge against the steel 120s), so I guess they’d be stuck in the pouring rain. After careful consideration, we head out, with a watchful eye on the radar, ready to dodge storms if needed.

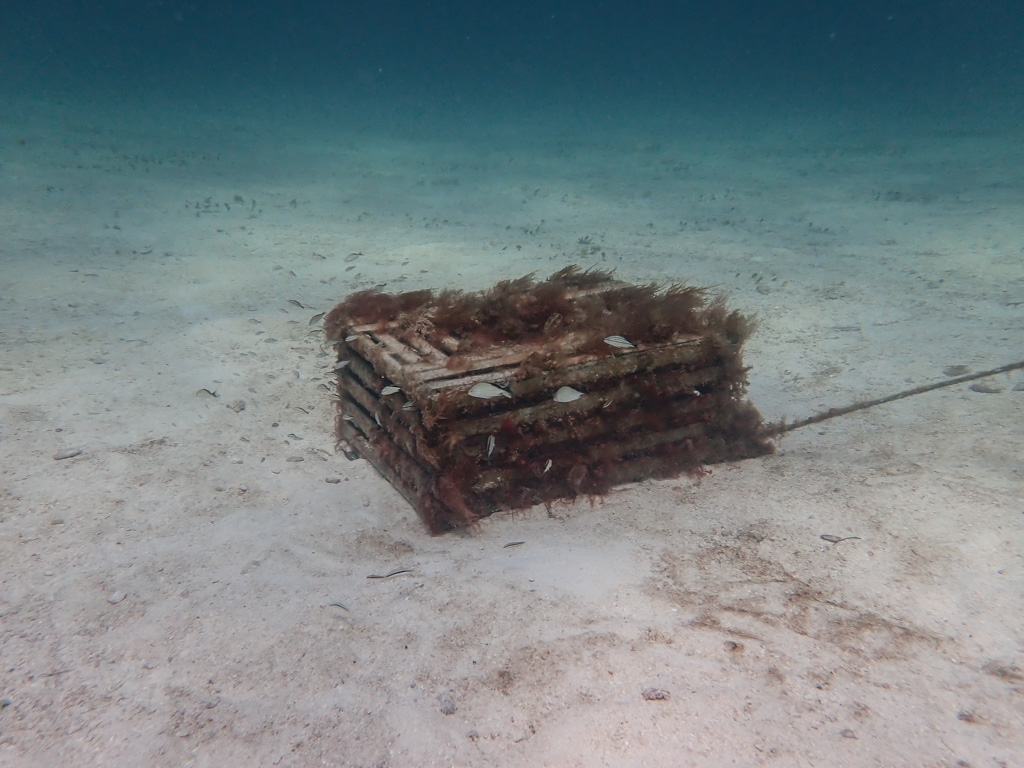

Removing derelict traps is no joke. A lot of traps are weighed down with ballasts, which are concrete slabs poured into the bottom of traps to keep them on the ocean floor. Lobster traps are by far the heaviest, made out entirely of wood and concrete, and can weigh up to 70 pounds. Wet and biofouled, ours have weighed in at over 100 lbs. It usually takes two lift bags to get them to the surface. This requires careful coordination between a buddy pair to make sure they are filling each lift bag with air at the same time so that the trap rises in a controlled manner to the surface. At one dive site, Rachel Fisher, Amanda Rivard, and I follow a line of traps for a couple hundred yards, but for what feels like miles as we kick into a strong current.

As soon as you think you are exhausted from digging broken traps out of the sand, swimming against strong current, and untangling heavy lines fouled with sponges, algae, and (my favorite) fire coral, you find yourself up on deck hauling in trap after 70 freaking pound trap. Pretty quickly you find yourself excited to get back in the water, and so the cycle continues. Back at the park headquarters, all the debris needs to be sorted, weighed, and taken to dumpsters. It’s challenging work, but I enjoy getting to be with a team of upbeat, funny, and motivated people. While having mostly female teams can still be a rare occurrence in many scientific fields, Biscayne’s divers set amazing examples to look up to, and they kick some serious butt. I’m thrilled to get to work and learn alongside them.

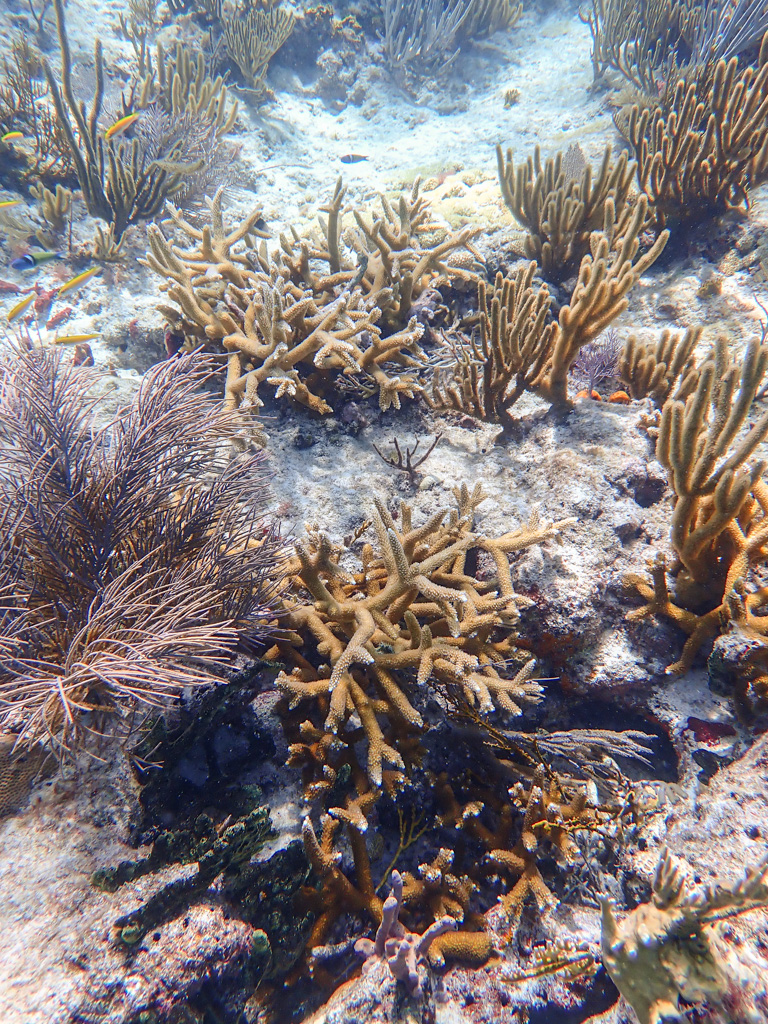

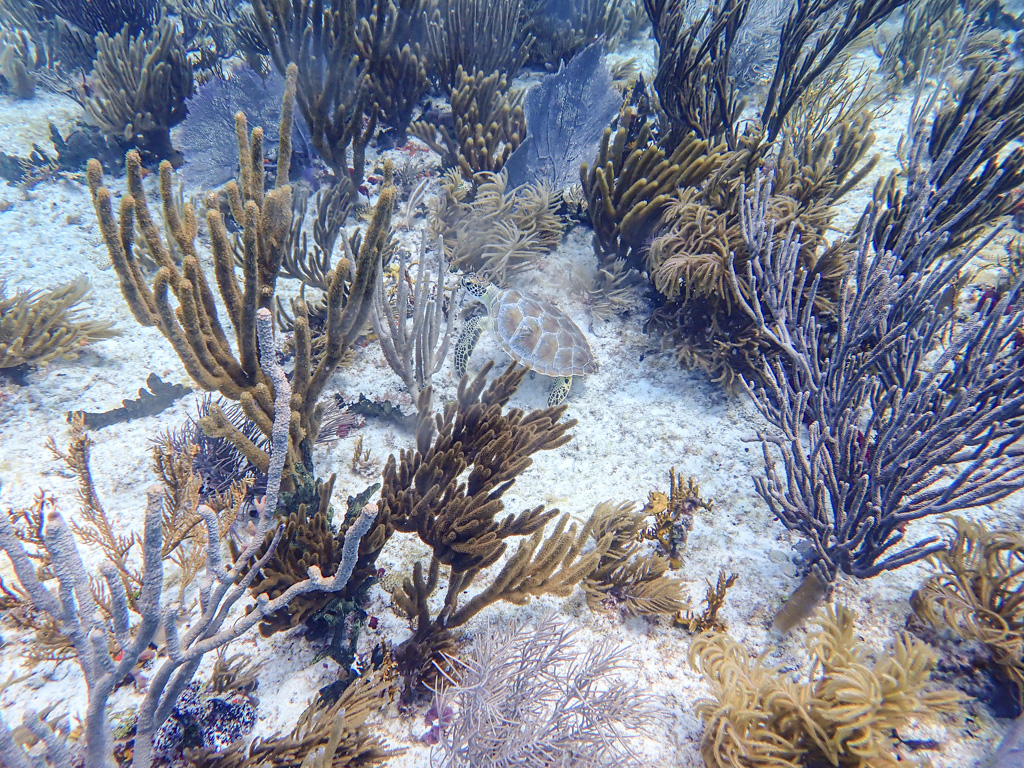

While I admit I spend a good part of my dives staring at the bottom and cursing traps through my reg, Biscayne National Park refuses to be ignored. On one dive, loaded up with a plethora of lift bags, clips, and mesh bags, we descend onto a beautiful reef with a friendly turtle, nurse shark, and even a moray eel! If my internship ended the next day, I would be content with all I saw! Even more exciting is our second dive. Amanda Rivard picks out a reef patch for some scouting work that has an average depth of around 15ft. At first, it seems devoid of hard corals but is a beautiful garden of purple and orange gorgons and sponges. Then, as we hit the end of the patch and start returning on the West side, I notice Rivard freaking out.

My concern turns to amazement as I see the staghorn coral, Acropora cervicornis (Acer), littering the side of the reef patch. Rivard, Delaina, and I all look at each other in disbelief. Seeing healthy Acer in South Florida is now rare, as the compounding effects of extremely warm temperatures in the summer and disease outbreaks reduce whatever populations are left to deeper reefs (National Park Service). Observing this coral growing pleasantly in about 12ft of water is mind-blowing and so exciting. When we get on the boat, Rivard immediately contacts the restoration team. These corals are large enough to spawn, meaning they could add genetic diversity and heat resilience to the coral restoration nursery.

It’s easy to fall into a rut of only seeing environmental destruction in the field and feel pretty pessimistic about the future of our natural world. Getting to see this resilient coral, which has seemingly defied two recent heat waves, hurricanes, and the pressures of marine debris from fishing, gives me hope. Apparently, I give the Biscayne team hope because they joke they should start taking me on each dive as a lucky charm after our day of turtles, sharks, coral, and more.

On the last day of trap removals, we head out on the Bay as offshore weather is a little too spicy for diving. We have a tough tide window to work with, and end up doing a lot of wading to get to traps too shallow to reach with the boat. At one point, I reach to grab a trap buoy, and end up back-flopped, belly up, staring at some clouds while my legs are bent at 90 degrees, disappearing in mud up to my knees. I was hoping no one saw, but when the water had drained from my ears and I pulled the sargassum off my head, I found an entire boat of people laughing at me. The wind is strong, and Delaina and Shelby rise to the challenge of keeping our flat-bottom boat (fondly nicknamed the “hockey puck”) from sliding all over the surface as we try to pull up to traps. I get to meet beloved long-time volunteers Suzy Pappas (Coastal Cleanup Corporation) and Frank Reyes (Mangrove Sasquatch), who also each coordinate beach cleanups and community outreach events in their own time. The stewardship that they and other volunteers show to Biscayne National Park and the surrounding area is a testament to how dedicated they are and how beloved the park is.

By the end of derelict trap week, we have removed over 85 traps, 5300+ pounds of debris, and approximately 2.6 miles of trap line. Countless stone crabs, blue crabs, lobsters, and other bycatch like nurse sharks were saved from derelict traps. To be clear, the fishing community was not being robbed of its dinner! Most of these traps were super old (besides being illegal) and would have never been found again. One of the teams was also able to save a sea turtle entangled in trap line, highlighting the danger of this marine debris and the importance of removing it.

At the end of the week, with the little free time I should have used to sleep, I’m able to connect with the 2025 OWUSS REEF Intern, Imogen Parker. I attend a coral outplanting workshop with the organization I.Care in the morning and then join her on a boat ride to one of I.Care’s sites. Getting to carefully clean algae off the outplanted coral bases was a peaceful end to a strenuous week of diving. The divemaster literally had to take the toothbrush out of my hand to tell I was done with my site. I personally think there were a few more pieces of algae that needed some attention. Finished with our sites, Imogen and I had fun getting to goof off together, and we ended International Women’s Dive Day with some fish tacos.