Good afternoon from Virgin Islands National Park on St. John! I’m here for two weeks of “fish blitz,” a collaborative, multi-agency effort to survey and monitor fish and benthic communities in the US Virgin Islands. The Virgin Islands National Park, the National Park Service South Florida/Caribbean Network Inventory and Monitoring office, NOAA, Nova Southeastern University, University of Miami, University of the Virgin Islands, The Nature Conservancy, and the Virgin Islands Department of Planning and Natural Resources have been working together for over a decade in the Virgin Islands to map the benthic habitat around the islands and document long term trends in fish and coral populations. This is an all-star team of distinguished experts in their fields, and it’s an honor to be here working with them.

NPS I&M ecologist and my coordinator Mike Feeley met me at the Miami airport and we were coincidentally seated next to each other on the flight to St. Thomas. We stayed in the airport for some time as the team of scientists, recognizable by their bags of dive gear and jovial greetings, aggregated by the baggage claim. This is the first year surveys are also being conducted on St. Thomas, so there was much reshuffling of gear and discussion of logistics as we sorted out who and what would go where. Eventually the St. John crew assembled and hopped on the twenty-minute ferry to the 20 sq mi, 5,000 person island that would be our home for the next two weeks.

The Virgin Islands are a sharp contrast to the smooth topography of the Florida Keys: steep green mounds rising abruptly from the ocean, dotted with cactus and spindly, windswept palms we affectionately call “Truffula trees.” As we arrived in the colorful town of Cruz Bay, which sported residual decorations from the Carnival celebrations that had ended two days previously, the skies opened with drenching rains. Rob Waara, another I&M scientist, picked us up at the dock, and careening up and down mountainous, narrow roads, and around impossibly sharp curves in the downpour was an exciting first introduction to the island, all the more so because we were driving on the left side of the road.

Staying in housing with the team, I’ve enjoyed the chance to get to know some of the scientists and hear about their different agencies, and participate in group dinners and data entry activities. Each morning we cram into our rented SUVs and zoom up and down to the National Park offices, known as the Biosphere (short for Virgin Islands National Park Biosphere Reserve). In the absence of heavy rains the roads are no less eventful as we dodge hidden speed bumps and the dogs, cats, donkeys, chickens, iguanas, mongooses, and people that roam nonchalantly in the streets.

At the Biosphere we discuss site assignments for the day and gather gear, which we drive down to the dock and load on the NPS boats Acropora, Leatherback, and Stenopus. We take everything we need for a full day of surveys, usually five to seven or even eight dives: an exhausting day. The nature of coordinating fifteen researchers and three boats has given me ample opportunity to nourish the local mosquito population.

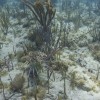

The surveys are conducted at randomly selected sites all around St. John, and we record data on the type of benthic habitat, coral populations, fish populations, and water quality. The three main surveys for this project are fish counts, LPI, and demo. For fish counts, a diver spools out a 25m transect in a random compass bearing and records the number and species of all the fish he or she sees on two meters either side of the line and up the height of the water column. For certain indicator species, like snappers and groupers, the diver also records length in 5cm increments. LPI stands for line point-intersect, and this diver records what is present on the benthic (seafloor) substrate on 100 points in 20cm intervals along the 25m transect line. Afterward, he or she also notes the presence of certain endangered species of coral, and spiny lobsters, Diadema urchins, and queen conch within 2m on either side of the transect line. Demo, short for coral demographics, consists of identifying and measuring the longest diameter, perpendicular diameter, and height of every coral structure greater than 4cm on a 10x1m transect. The demo diver also records the percent total and recent mortality on each coral structure, and the presence of bleaching.

I’ve been on Stenopus with Rob Waara, NOAA Biogeography branch scientist Mark Chiappone, NOAA Southeast Fisheries Science Center ecologist Margaret Miller, and Virgin Islands National Park science tech and boat driver extraordinaire Adam Glahn. We were originally assigned all demo surveys since they are typically the most time consuming, but by midweek incorporated LPI and fish counts as well. Virgin Islands National Park Natural Resource Manager and Park Dive Officer Thomas Kelley was kind enough to lend me his fish guide to brush up on species identification, so I’ve been shadowing Rob on fish counts in hopes of contributing to data collection later in the trip.

Diving for a field mission like this is very different from recreational diving or even the routine work diving we did in Biscayne. These scientists have limited time and resources in the field to collect as much and as rigorous data as possible, and are straight to business underwater. Intensive, repetitive diving across multiple days is taxing and risky: in addition to the usual concerns of diving (buoyancy, air consumption, paying attention to one’s buddies, dealing with conditions like high currents or low visibility, etc.) and the mental exertion of measuring dozens of small corals or tracking fast moving and often similar looking fish while following standard operating procedure for the surveys, these scientists must be aware of how previous dives affect their blood oxygen and nitrogen content, which can constrain the length of a safe dive. Our mantra “safety before science” is of the utmost importance, and sometimes we’ve made the tough but conscientious decision to end a dive mid-transect to stay within safe decompression limits and make sure everyone gets to the surface together. I certainly struggle to focus on even simple tasks underwater—there’s so much to think about and look at, even before the nitrogen narcosis sets in—so I’ve been extremely impressed by the professionalism and efficiency these scientists exhibit on every dive.

My focus on fish species has made it painfully apparent how depleted the populations are here. Particularly noticeable is the absence of large predators: snappers are few and far between, and groupers nonexistent. The few fish we do see are the usual prey base for these larger predators, what we in the scientific community refer to as “little dicky fish.” I’m getting tons of practice identifying the various intermediate stages of juvenile wrasse and parrotfish, and the dickiest fish of them all, Halichoeres bivittatus. The loss of large groupers and snappers, undeniably tasty fish, is a definite sign of overfishing. Although most of St. John and its surrounding waters are protected by Virgin Island National Park and Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument, recreational fishing is allowed, and the park just doesn’t have the resources to control illegal commercial activity.

The loss of large top predators is problematic for marine ecosystems because larger fish are generally more fecund, and because they are often keystone species that regulate the food web. Without them the ecosystem is unbalanced, with consequences cascading down trophic levels. To make matters worse, this area is a hotspost for ciguatera, a toxin in reef plankton that bioaccumulates in fish and causes severe neurological symptoms in humans. Large fish at higher trophic levels have more ciguatera toxin in their tissues, and thus are more dangerous to eat. These big predators here have been unsustainably fished and they aren’t even edible! Encouragingly, I haven’t seen a single lionfish, but they do live here, and an overfished, unbalanced community like this will be more vulnerable to their inevitable invasion.

This week has also had its share of the adventures and obstacles inherent to field work. As a rookie intern I’ve found our escapades exciting and amusing, but to these seasoned scientists they seem more routine. We had rough seas on the first few days, and waves would slosh through the dive door as we returned to the boat, overwhelming the bilge pumps. It was definitely a new experience to be assembling my gear while standing in a foot of water in eight-foot waves. Midweek, as we apprehensively followed wind forecasts, I was worried that tropical storm Chantal would bring me another lesson in weather-dependency, but she passed to the south of us and we took advantage of St. John’s complex geography to find protected sites, and actually had great conditions. The next day it wasn’t weather but equipment that stymied us: just past the harbor, our port engine emitted a fractious outburst and refused to take us further. Our assigned sites were all the way around the island and we didn’t think we could make it on one engine, so we headed back to the dock. Fortunately the park’s mechanic Peter was on site, and discovered that part of the compressor had exploded, leaving a golf ball sized hole. Luckily he had an extra on hand and we were soon underway, and were still able to finish five sites.

The camera has been an adventure in itself. A few minutes into my first dive of the trip, I glanced down to a horrifying sight: a small pool of water collecting inside the dome port! Luckily it was a shallow dive and I was able to pop back up and hand it off to Rob and Adam on the boat. After a careful fresh water rinse, overnight blasting with AC, and some O-ring grease, the camera is fully functional, to my immeasurable relief. I haven’t had any more flooding scares, and am hoping this means I’ve gotten them out of my system. In the deeper and less clear waters here I’ve been experimenting more with the strobes, with mixed and sometimes frightening results. Everyone has been extremely patient and tolerant of me flashing haphazardly in their faces in my attempts to snap glamour shots. I’m absorbing all the advice I can get and hopefully will improve via trial and error over the next week.

The next week will bring some new people and reportedly smooth conditions. I’m excited for more diving and hope to get in on some data collection!

- Rob Waara conducts a fish count.