You might think living on an island of 0.06 square miles during a dive stand-down could get tedious, but my DRTO days have been astonishingly eventful.

We continued our turtle monitoring each day, on Loggerhead as well as on Garden Key and the smaller sandy keys. Luckily we didn’t find as much activity as we did that first day, but it was nevertheless exhausting, sweaty work. I’m getting more familiar with how to distinguish between the tracks of green and loggerhead turtles—loggers have more comma-shaped front flipper prints and crawl with an alternating gait, like a trotting horse, while greens have straighter, choppier strokes and move with both foreflippers at once. On slopes and turns, however, it can be difficult to distinguish between the two, and naturally our dear turtles move exclusively in turns and on slopes.

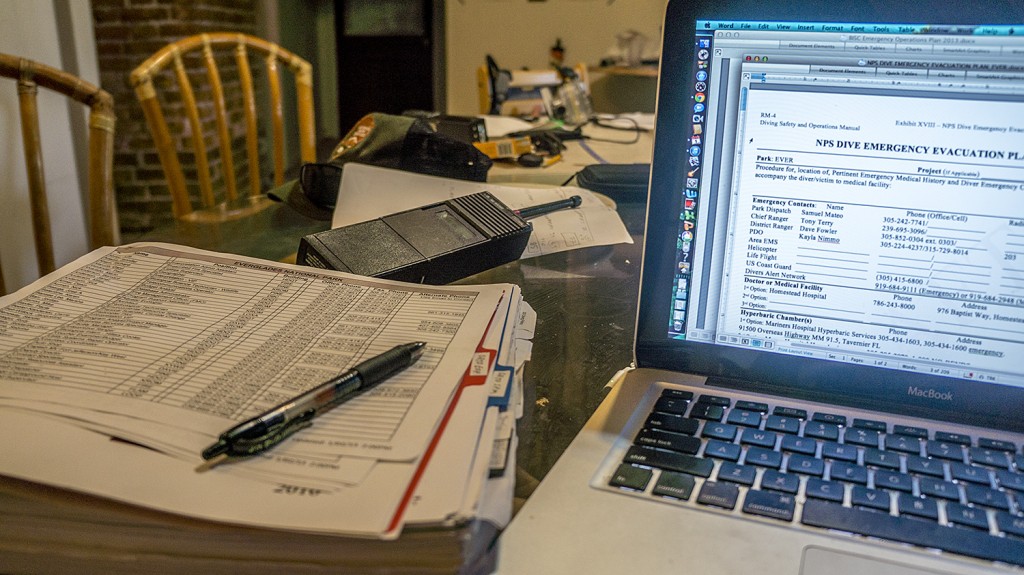

Ever hopeful of imminent stand-up (this is actually the official opposite of stand-down), we also scoped out potential dive sites using GIS and tide information, and prepped OSHA-mandated pony bottles, tiny auxiliary air tanks for out-of-air emergencies. We also wrote and revised emergency procedure documents and safe practices paperwork for the park to be completely ready to go at a moment’s notice. The long days at home after turtle walks gave us plenty of time to think about and enjoy our favorite mid-morning meals, second breakfast and first lunch.

A USGS group has been here tagging turtles all season, and is at the stage of retrieving tags to download and process the collected data. Turtles nest several times during the nesting season, returning every few weeks, so they can track their movements and catch them after they come ashore to nest or rodeo them as they surface in the water. Their field mission had come to a close and two turtles with accelerometer tags still hadn’t returned, so USGS biologist Kristen Hart asked if Kayla, Ryan, Lee Qi and I could monitor East Key for the night and collect the accelerometers if the turtles came to nest. Tagged turtles are given unique names, and we were looking for Luly and Mossey, both loggerheads. The accelerometers measure turtle movements at an extremely fine scale—90 data points are collected per second—and are used to record the turtle’s behavior and movements during the nesting season. If not retrieved, the tags (which don’t come cheap) and all their data are lost when turtles naturally shed their scutes (the “scales” on their shells), so finding and retrieving them was extremely important to the project. If we found a turtle with an accelerometer we were instructed to record her movements to the second as she nested before removing the tag; this information would be used to help interpret the massive amount of accelerometer data. For this we synchronized our wristwatches to time.gov, a task that required an unanticipated level of agility and wit.

We then geared up for our scientific slumber party, packing red headlamps, snacks, and beanbag chairs and boat seat cushions for sleeping. As the sun went down, law enforcement officer Wayne Mitchell kindly took us out to East Key and dropped us off on the small sandy island. We divided the night into four two-hour shifts, during which the person on-duty would walk the perimeter of the island every half hour. As the brilliantly pink clouds faded into gray and before the half moon rose in the wee hours of the morning, the sky was lit only with the faint Fort Jefferson harbor light in the distance, occasional lightning in the distance, and the incredible multitude of stars. Lee Qi, on the first watch, quickly found a green turtle on the beach, and since Ryan and I had never seen a green nest before we headed over to watch. Turtles, greens especially, will spook easily and may false crawl if they see or hear people as they look for a nesting site and start digging, but can be closely approached as they lay their eggs provided we stay behind them and remain reasonably quiet. We kept our distance, turned off our lights, and hunkered down as quietly and motionlessly as possible to wait for the appropriate time to approach. Just as we started discussing in low whispers that it had been a while since we had heard digging and could probably try to sneak a peek, Kayla radioed that the green had crossed to the other side of the island to nest, and we realized that the dark lump we had been so assiduously and cautiously monitoring was actually a small bush. Luckily we were soon distracted from our embarrassment: within a few minutes, Kayla excitedly radioed that Mossey was on the beach! By the time we grabbed the corrals and came over, she had started to lay her eggs. We were able to approach close enough, always staying behind her so she couldn’t see us, to actually see the eggs dropping into the nest. Kayla meticulously recorded her every movement as sanctioned by time.gov.

Abruptly, Mossey finished laying her eggs and started burying the nest. She first used her surprisingly dexterous rear flippers to delicately fill in the egg cavity for several minutes before incorporating her larger front flippers, vigorously spraying us with sand. As she turned to go, it was our time for action. Ryan and I grabbed the heavy corrals, hinged plastic squares that form a box around the turtle and are connected with plastic stakes. Loggerheads can weigh upward of 500 lbs and corralling can be a strenuous, frantic, and sandy activity. Luckily Mossey is on the smaller side and Ryan, Kayla, and I were quickly able to restrain her, but I could feel how strong she was as she lunged at the corral walls. Kayla removed the accelerometer with a hacksaw while we scraped off the barnacles growing on her carapace. Mossey alternated between doggedly straining at the corral and appearing to nap, emitting little grumbly turtle snores. We released her, cleaned and streamlined, and she hastily made for the water without so much as a backward glance.

Mossey rests in the corral. Part of the project procedure includes taking flash pictures of the turtles for identification purposes, so Kayla let me take a few after Mossey finished nesting. In general, however, it is best to refrain from flashing the turtles.

Triumphant, we returned to camp to get some sleep before our assigned watches. My walks between 1am and 2:30am were brilliantly illuminated by the moon, making my headlamp unnecessary. Patrolling every half hour means the tracks will be fresh, so we walk at the water’s edge and can quickly identify new tracks. On a few surveys I stopped at fresh tracks by the water’s edge, glanced up to follow them, and was startled by a turtle only a few feet away. I saw a few more greens making their way up the beach, but no Luly, who did not come nest that night. Between walks I would nestle into my boat cushion and life jacket pillow for a few minutes of sleep before heading out for the next round. Wayne came to pick us up around 6am, and as we packed up to leave a bold green crawled up right by our camp! Seemingly unperturbed by our loading activities, she continued to heave herself along the beach as we headed back to our waiting beds on Garden Key. Kristin is going to keep coming back in hopes of catching Luly, who is still in the DRTO area; meanwhile, Mossey is hightailing it to Mexico—you deserve it, girl! You can track Luly and Mossey (and the other DRTO sea turtles) at seaturtle.org.

In the last few days of my stay at the fort, we got word that we would be able to dive! We would follow OSHA standards as commercial divers, but could ignore the stipulations about outdated equipment per “accepted community standards.” There was much mirth and rejoicing. Briefed and checked out, laden with our pony bottles in addition to the dive flags, flashlights, data clipboards, lionfish spears, and buckets we needed for data and lionfish collection, we were overheated and clumsy in the boat and oddly balanced in the water, but we were diving! Per OSHA standards we conducted the lionfish surveys with one buddy team in the water and two people topside, one Designated Person In Charge and one fully geared standby diver. For the surveys, one diver would carry the spear and a bucket to hold the lions, and the other carried a clipboard to record the time, depth, habitat type, and behavior of each lionfish captured. He or she would also time the survey with a stopwatch, stopping the clock from the second the lion was spotted to the time the search resumed. They’re using shorter spears here, which make it easier to nab lions in tight spots, and I’m getting handier with headshots. We were even treated to a day of the perfectly calm weather we had been so loathe to miss last week. It was pure joy to skim along flat water in a fast boat, the only movement on the surface the ripples of flying fish skipping out of the way of our bow.

On the way to our dive sites a small pod of dolphins, mothers and juveniles, graced us with a visit. They approached us and came right under the boat but declined our offer to play in our wake. They definitely brought us good luck—when Ryan and I went in we caught a record fourteen lions! Sitting topside was a pleasure as well: there is nothing so peaceful as floating on quiet water, circles of placid bubbles telling you your friends are happily breathing below the surface.

Back at the dock we would record initial data for our catch. In such a remote location with our supply of groceries dwindling by the end of the stay, there’s no sense in wasting a source of free protein, so the DRTO interns put an additional step in lionfish processing: measure, weigh, fillet. Carefully avoiding the venomous spines, we filleted our larger catches, throwing scraps and skins to the three goliath groupers that lurk under the dock, knowing that the fish cleaning station means free meals. Gut content analysis was left for a potential future bad weather day, a decision to which I was not opposed. Over the next few nights we enjoyed grilled lionfish and fresh lionfish ceviche.

To round out my turtle nesting experience, I also jumped at the chance to accompany Kristin to excavate a hatched loggerhead nest. Three days after someone observes hatchlings or their tracks, the nest is excavated to collect data on how many eggs were laid, how many didn’t hatch and why, any evidence of predation, as well as to release any lagging hatchlings. We returned to East Key, which in the daylight resembles a sandy pincushion so crammed is it with PVC-marked turtle nests. Kristin expertly dug through to the nest, and found two tiny hatchlings, while Lee Qi sorted the hatched shells and pipped eggs (hatchlings unable to make it out of the egg shell). We packed the hatchlings in wet sand and took them home with us to be released from Garden Key later in the evening. This turtle was productive—she laid at least 116 eggs. Kristin collected the yolks of the ten unhatched eggs to be taken back to the lab for study. There is still ongoing research on how the Deepwater Horizon spill is affecting turtle nesting, and Kristin explained that DRTO essentially acts as a control site since it’s far from the spill.

I’m getting into the swing of things here with turtle protocol and the fort routine, which must mean it’s time to move on. It will be interesting to see how the stand-down has affected the rest of the National Parks that I’ll visit. I’m glad that I was in DRTO with so many terrestrial projects going on, and also that my being here permitted everyone else to dive—with the rotating schedule, Kayla doesn’t always have the requisite four people for an OSHA commercial dive team (three-person dive teams are permitted if the diver is tethered to the boat, but this is impractical and even dangerous for hunting lionfish in complex habitat). We were lucky: in parks with smaller dive programs they might not be able to dive at all or get any work done until this gets sorted out. Thank you so much to Tracy Ziegler for coordinating my stay, Kayla for supervising me and doing everything she could to get us in the water, and everyone at the fort, particularly my fellow terns. You guys are awesome, and I hope you get to dive!

Thanks for a great description of your turtle adventures. When I was a very green ranger there about 50 years ago, turtle nestings were not nearly as common, so it was exciting to see the few crawls, mostly on East Key. Never got to see the actual nesting process, though, so I envy you your opportunities. Thanks for all your efforts on the part of the turtles and science.