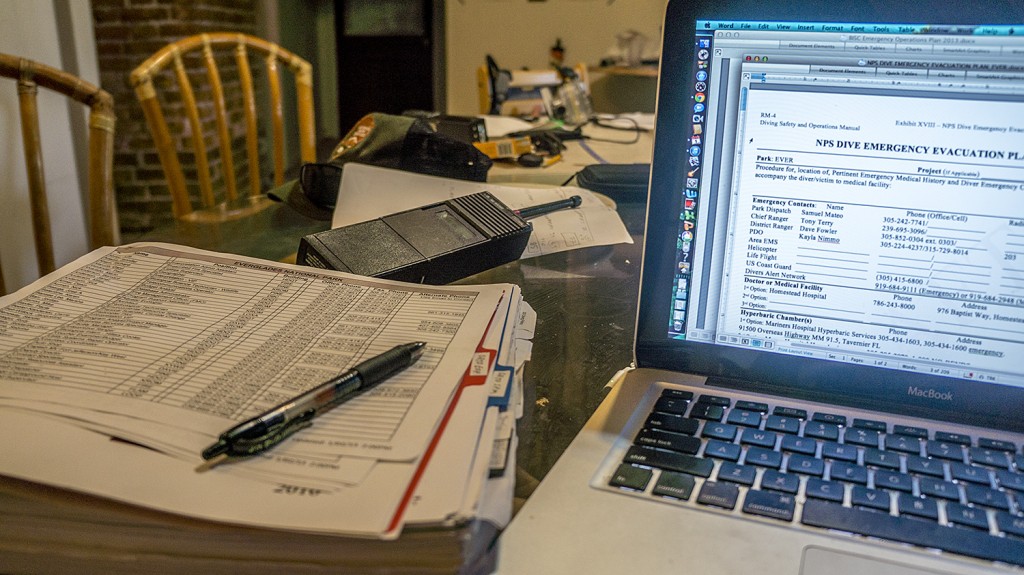

This week I left the warm coral reefs of the Caribbean for a five-day Kelp Forest Monitoring cruise in California’s Channel Islands National Park. After some 23 hours of traveling I made it to the park headquarters in Ventura Harbor, where marine ecologist Josh Sprague met me and led me to the Sea Ranger II, the 58-foot boat where I would spend the night and then the following five days. A quick update on the stand-down: the new dive policy has been written and approved, and now individual parks are in the process of adjusting their dive programs to be compliant with the new policy, resubmitting their qualifications, and completing the type of updates and rewrites of emergency protocols that I was working on in DRTO. Fortunately for me, the Channel Islands’ dive program has been extremely on top of this, and was the first in the Pacific-West region to be stood up (Park service lingo differs slightly from dating lingo, I’ve found). One hundred twenty-four pages of dive policy and a 65-question test later, I was ready to dive with them.

On Monday morning, I awoke to the rest of the crew beginning to load the boat. I met marine biologist and Regional Dive Officer David Kushner, biological technician and Park Dive Officer Kelly Moore, boat captain Keith Duran, and biological technicians James Grunden, Mykle Hoban (a former OWUSS AAUS intern), Jaime McClain, and Doug Simpson. To my utter joy, they were filling the boat’s refrigerator and cabinets with all the most delicious Trader Joe’s snacks I could possibly desire. Loading and logistics complete, we were off for a week of intensive kelp forest surveys.

A native Californian, I’m partial to foggy seascapes, and I was immediately taken with the Channel Islands in their understated loveliness. On land, the islands offer rich cultural history and biodiversity, with endemism (when species are unique to the islands or even an individual island) comparable to that of the Galapagos. On this boat-based mission, however, I only viewed the terrestrial resources from afar: we were there for what was below the surface. The marine life here is particularly interesting because these islands lie on the convergence point of cold currents from the Arctic and warm currents from Mexico. These currents bring together warm- and cold-water species to create high biodiversity, and their mixing churns up nutrients from the deep ocean, a process called upwelling, which supports a large biomass.

Five of the eight Channel Islands and the waters out to one nautical mile from their shores were designated as a National Park in 1980 with a specific view toward long term monitoring. The Kelp Forest Monitoring (KFM) project began in 1981, and is the longest running monitoring program in the National Park Service. They started with thirteen permanent sites, and now regularly survey 33, taking data on the size and abundance of certain indicator species at various levels of the food chain. The sites represent a broad range of temperatures and levels of protection. The state of California controls the marine resources and allows fishing within the park, but eleven no-take Marine Reserves within the park boundaries were established in 2002. The KFM project added sites inside and outside these reserves to assess their efficacy. Their data helps inform the state’s management decisions, and demonstrate how policies affect the marine ecosystem. What’s especially cool about the KFM project is that it provides long-term fishery-independent data. Most of the information we have about fish populations comes from studies of what fishermen catch, like the creel surveys I did in Biscayne. Fishery-independent studies, while harder to perform, provide a much more accurate and comprehensive picture of what exists in the marine ecosystems, as opposed to what fishermen are targeting in response to demand. Dave also explained to me the value a multi-decade dataset, a rarity since the usual span of a funded study or PhD project is only a few years. Evaluating trends over so many years has yielded some surprises. What park scientists thought they understood about weather patterns and population trends is changing as the broader view reveals larger trends that a five- or even ten-year snapshot would fail to capture. To continue this legacy of rigorous data collection, the KFM team goes out every other week from May through October to complete surveys on all 33 sites.

That first afternoon, we pulled up to the closest island, Anacapa, and jumped in at Landing Cove. I was assigned 5m quadrants with Kelly, for which we swim along either side of a 100m transect and count any giant kelp, invasive sargassum, and two indicator species of sea star, giant-spined and ochre, within one meter of the transect line, tallying them in five meter increments. When we’re done, we go back and do Macosystis (giant kelp) counts, which involve measuring the largest diameter of the holdfast and counting the number of stipes (like stems) present at 1m height for 100 total individuals. All around us, other members of the team surveyed the benthic substrate and the abundance and size of fish, sea stars, urchins, sponges, and other indicator species.

We had calm winds and relatively flat water, so below it was beautifully clear. I’ve heard kelp fronds compared to stained glass, and light filtering through the kelp into the hush of the water did evoke a cathedral-like sense of sacred. California’s giant sequoias have the same effect. The kelp forest has a more reserved color scheme than the riotous Caribbean coral reefs, which makes the occasional bright colors—the vivid purple of sea urchins, the deep orange of the garibaldi—all the more striking. I was enthralled by the minutiae all around the transect: it was incredible to be diving among the creatures that had inhabited the touch tanks of my childhood.

Calm weather meant great conditions, and also that we went to the more exposed sites and the northern islands, which most visitors never see. I was thrilled to be so lucky, but it did mean we went to all of the coldest sites. Despite the four years I spent in Boston specifically training for situations like this, I was hopelessly chilly. People were kind enough to loan me extra gear, but even in a 7mm wetsuit, two vests, two hoods, and thick gloves, my teeth were chattering on the regulator by the end of each dive. This was partially because the team goes on extremely long dives to collect as much data as possible. I’m used to dives between 30-50 minutes, and here they were often above 80. This makes each dive incredibly productive, but I definitely wasn’t as useful a contributor as the dives went on and I lost sensation in my fingers

I’ve been getting some questions about how we collect data underwater, and it still blows my mind each time so it’s well worth some description here. We record data on UNDERWATER PAPER. I haven’t actually asked what it’s made of yet, but it maintains most of the properties of ordinary paper while being completely waterproof (and slightly shiny). The paper can be attached to clipboards with rubber bands, as we did in St. John, or slid into a frame of plastic slates and secured with wing nuts, as is customary in DRTO and the Channel Islands. The preferred writing implement for underwater science is the kind of pencil you may remember from early elementary school with several plastic segments of graphite that can be pulled out and then inserted in the top of the pencil to advance the next segment. Regular mechanical pencils rely on metal springs that quickly become useless in salt water, so these all-plastic instruments are premier (Their main weakness is that the loss of a single segment renders the entire pencil useless, but this can be mitigated with a spare pencil or a stray urchin spine). These pencils are secured to the slates with rubber tubing (which is much more reliable than trying to stick it in a BCD pocket or just holding it, which is how I probably doubled the Virgin Islands National Park’s pencil expenditures for next quarter). One of the most important inventory decisions scientists must make is which pattern to select for their pencil orders. This is also an important choice on each dive. I was particularly attached to a pencil festooned with purple whales in St. John, although I would settle for the one covered in $100 bills. In the Channel Islands I was always happy to get a slate with a glitter pencil, but wasn’t going to complain about puppies or bumblebees.

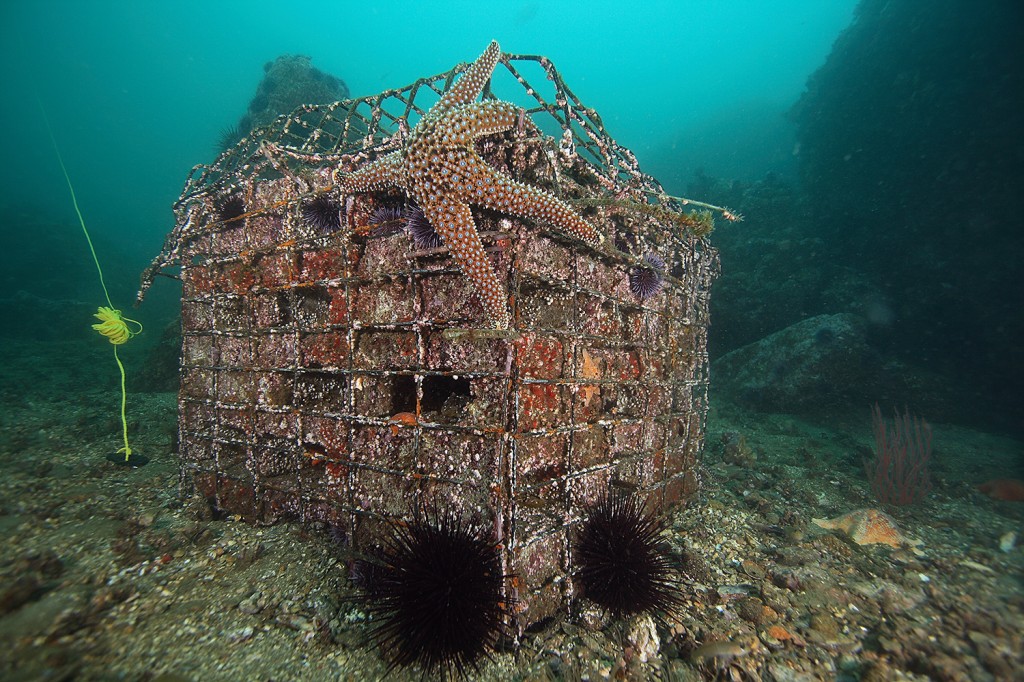

On subsequent dives and sites I put segmented pencil to underwater paper for more 5m quadrants and Macrosystis counts, diving with Dave, Josh, and Mykle. On the second day, diving off Santa Rosa, Dave showed me another survey type, Artificial Recruitment Modules, or ARMs. Many kelp forest critters, especially juveniles, live under rocks and in crevices, but it’s difficult to survey them in a controlled way since different divers might have different rock-turning capabilities. By creating artificial rocks with halved cinder blocks, the KFM team has created a systematic invasive survey. They stack these cinder blocks in wire mesh boxes, leaving a “courtyard” in the middle, and periodically turn each over, take all the indicator species out, measure and record them, and put them back. This is useful for tracking recruitment, the rate of juvenile individuals reaching maturity. Opening the ARM was Christmas for kelp nerds. Dave turned over the first block to reveal an octopus guarding her clutch of eggs, and each new block was crawling with brittle stars, urchins, sea stars, and the occasional tiny crabs that would huffily scuttle away. Juvenile fish cowered in the center, and larger fish lurked nearby in case we overlooked anything tasty. The site’s resident harbor seal, whom Keith has nicknamed Chester the Molester, also stopped by to oversee the proceedings. There were far too many study animals to measure during the dive, so we brought our stash to the boat, where it joined several other similarly stuffed mesh bags from the other ARMs at the site. On deck, everyone grabbed a chair and a set of calipers, and for the next several hours we grabbed urchin after urchin, sea star after sea star and called out their measurements to the furiously recording data collectors (this recording was executed on standard land paper).

On Wednesday evening we reached San Miguel, the northernmost and least accessible island. Here the kelp was so thick that we were diving in near darkness, and the water was freezing! On deck we stay warm with a hot water hose that we regularly stick down our wetsuits (boat norms differ slightly from normal norms, I’ve found), huge fleece-lined parkas, and lots of hot tea and cocoa. A buddy team is usually in the water at any given time while we’re completing a site, so there’s a fairly continuous rotation of dive preparation and dive recovery. For one of the surveys they use a full-face mask with surface supplied-air and a microphone system, so the diver can stay down longer and dictate data to someone recording on the surface (also done on land paper). We bustle around donning gear and passing around the hose to the constant sounds of Darth Vader breathing and rapid categorizations of the benthic habitat.

When we’re not diving, we’re generally sleeping or eating (The bounteous, nay, Brobdingnagian supply of snacks was defenseless against our onslaught). In the evenings there’s usually a fair bit of data processing and discussion before we eat dinner as a group. Members of the team switch off cooking for everyone, and their culinary abilities were uniformly outstanding. In transit we might have time to read on the fly deck or in the cabin, and one night we had a screening of Wedding Crashers, enjoyed with brownies à la mode.

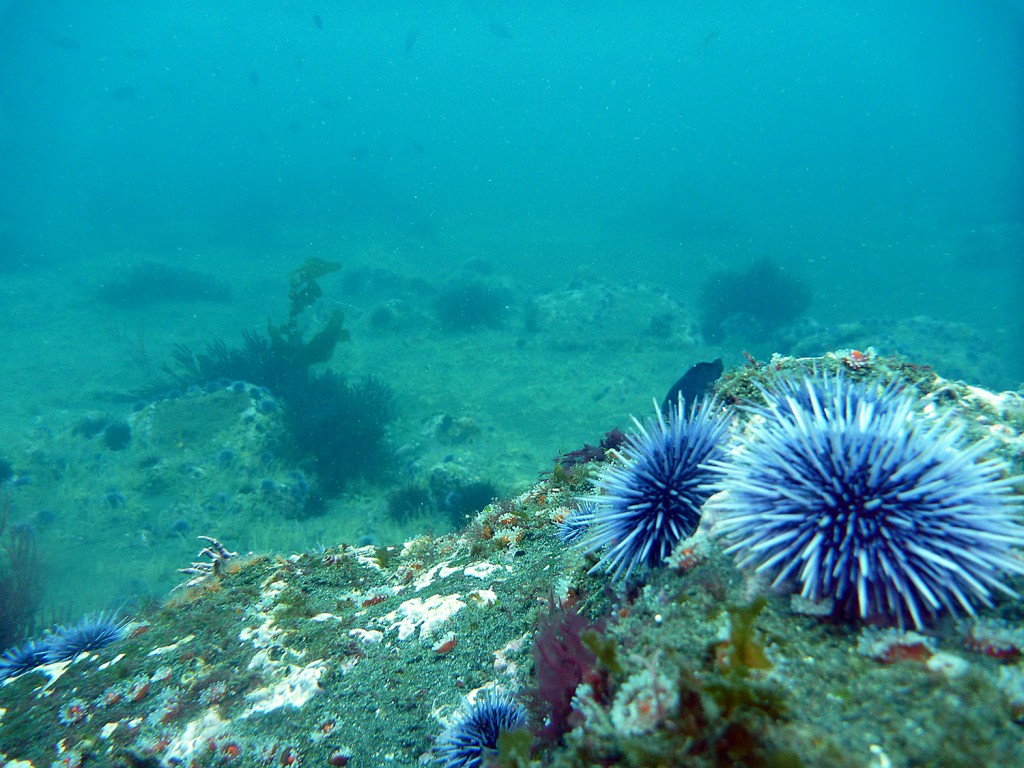

In sharp contrast to the dense kelp forests I saw on the first day at Anacapa, the urchin barren habitat outside the reserve illustrates the cascading consequences of overfishing.

On the last day, we had time for a few dives before heading back to shore. We anchored at Anacapa once again, but surveyed a site outside of the no-take reserves. The difference was remarkable. On this site, all we could see was urchin barren, a classic example of the cascading consequences of overfishing. With the removal of sheepshead and other fish that prey on sea urchins, the urchin populations exploded and grazed all of the kelp. Rather than forest, here was grassland, although the grass, on closer inspection, was the waving arms of millions of brittle stars. The water was clear and much warmer (60°! I could almost forgo the second hood!) (Almost.) and the surveys were quick with no kelp to count. Mykle and I brought some calipers to measure as many sea stars as we could, while sea lions cruised by in clear hopes of making mischief.

The cruise was all too short, but I was also looking forward to a family visit. In another bout of fortuitous timing, my return to Southern California was a few days before my younger brother’s move-in day for his freshman year at USC. I had a great weekend with the family exploring the Getty Museum and Venice Beach before braving the cattle round up of lanyards and shower caddies and frazzled parents that is moving into a freshman dorm. I bid farewell to the new college student and the new empty nesters, and set off to spend the next month in Hawaii.

Thanks so much to the KFM team for letting me tag along this week, feeding me handsomely, and loaning me all sorts of extra gear, not least of which the underwater camera I used to take all these pictures (The SRC camera is back in Denver for repairs, since it turns out my flooding troubles were not as over as I hoped. Luckily the camera is fine, but Brett is being kind enough to service the housing for me!). I had such a wonderful time, and will definitely be making a return trip or many to the Channel Islands.