It has been an incredible summer down on the Kenai Peninsula to say the least. It is hard to put into words how many new experiences I have had and how much knowledge I have gained over the past three months. I am endlessly grateful for OWUSS, AAUS, and Dr. Brenda Konar for allowing me to have this experience as the 2019 AAUS Mitchell intern.

In addition to diving in Kachemak Bay’s rich and diverse kelp forest ecosystem, I had the chance to work in the rocky intertidal, seine fish along the beach, survey marine birds and mammals from boats, operate ring and trawl nets, use underwater drills, and even hike upstream to sample a glacial stream. As an ecologist coming from Colorado with a background in tropical marine ecology, the cold water ecosystem of Alaska offered a new lesson just about every step of the way. It is one thing to learn about one of the most common examples of a keystone species, the sea otter, in an ecology class in a landlocked state, and it is another to be immersed in an ecosystem where the kelp-urchin-otter dynamic is occuring. I have come away from this summer feeling more confident as a scientific diver, possessing a strong drive to continue asking questions about this system, and being humbled at the wealth of knowledge and skills the amazing mentors I have had the pleasure of working with hold and are willing to pass on.

One of the most important pieces of advice I received before beginning this internship was to always say yes to opportunities. After three months of saying yes to every chance I got to go on a dive, go out on a boat, or help with something new in the lab, I have compiled a non-exhaustive list of firsts sprinkled with photos.

First…

- First time setting foot in Alaska!

- Put on a survival suit (just for fun)

Testing out a survival suit. Photo by Brenda Konar.

- Dive not in a 3mm wetsuit

- Dive in a drysuit

First dry suit dive! Photo by Brenda Konar.

- Sea otter in the wild

Otter raft. Photo by Emily Williamson.

The curious local otter in Kasitsna Bay. Photo by Emily Williamson.

- Whale!!! Yes, I freaked out.

- Sea star in the wild

Matching with a purple Evasterias. Photo by Tibor Dorsaz.

- Dive in a kelp forest

Nereocystis forest. Photo by Katrin Iken.

- First time catching a fish!

View from our fishing spot.

- First time working in the intertidal

Working in the intertidal in Kasitsna Bay. Photo by Katie McCabe.

The intertidal on Bishop’s Beach.

- Beach seine

Beach seining in Tutka Bay. Photo by Brenda Konar.

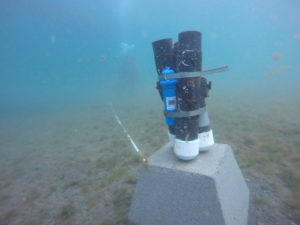

- First time operating an underwater drill

Post-drilling, we brought the SeaFET unit up to clean off growth and download data. Photo by Marina Washburn.

- Delightful experience of walking through knee deep mud near a seagrass bed

Stuck in the muck. Not pictured: my right leg that was buried in mud. Photo by Brenda Konar.

- 100th dive!!!

- Drove zodiaks

Photo by Marina Washburn.

- Seal in the wild

Seals! Photo by Tibor Dorsaz.

- Sea lion in the wild

- First time seeing an iceberg… this one surprised me, too

The Grewingk Glacier

- Taste of glacier ice

Photo by Naomi Hutchens.

- Sunset over Kasitsna Bay

Sunset view from the Kasitsna Bay Lab.

- Tossed a salmon

Seldovia salmon toss on the Fourth of July. Photo by Corey A.

- Saw a puffin

Puffin on the water. Photo by Tibor Dorsaz.

Lucky for me, this is not a list of lasts. Alaska has stolen my heart and I have decided to stay a bit longer than just one summer. In Spring 2020, I will be beginning my masters in marine biology at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. This means that I get to continue to learn and grow as a scientist under the mentorship of Brenda Konar, as well as return to the Kasitsna Bay Lab next summer.

This opportunity has been so much more than a summer internship. I have grown as an individual, a scientist, a diver. It has been a springboard for my career in marine ecology fostered by invaluable experiences and supportive mentors. I recognize that this field has been built by the scientists and divers before me and I am humbled by their contributions. As a member of OWUSS and AAUS, I hope that I can pay it forward so other young scientists like myself can continue to make their exciting lists of firsts. So, thank you to the building blocks of this experience: OWUSS, AAUS, the team at the Kasitsna Bay Lab, and most of all, Brenda Konar!

My wonderful team at the Kasitsna Bay Lab! Left to Right: Katie McCabe, Tibor Dorsaz, Liza Hasan, Andrew Scotti, Brianne Visaya, Brian Zhang, Emily Williamson, Brenda Konar.