Almost a year has passed since I started compiling my application for the OWUSS NPS internship. Although an organization I had known of and been watching for several years, I never had the “right” qualifications to apply. I knew 2022 would be my chance – I had finally formally completed my Rescue diver training, maintained active scientific diver status over the past several years, and would be graduating shortly, leaving summer open for new adventures and opportunities in learning.

During my first meeting with Dave Conlin (internship supervisor and Chief of the NPS Submerged Resources Center) and Brett Seymour (Deputy Chief), we wondered aloud if I could take advantage of my Canadian heritage and connect with our friendly neighbors to the north – the Parks Canada Underwater Archeology Team. After exchanging several emails, I soon learned they would have several projects ongoing this summer across Canada, from Lake Superior to the Canadian Arctic and eastern Labrador (did you know this is the only dive team within Parks Canada?). I was beyond thrilled when Jonathan Moore (Senior Underwater Archeologist) put me in touch with Brandy Lockhart (Underwater Archeologist and project lead), putting the pieces of the puzzle together for me to join them in Red Bay, Labrador, at the Red Bay National Historic Site/UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Overlooking Red Bay on the southeastern shore of Labrador. Photo: Todd Stakenvicius

The Parks Canada logo (the Canadian NPS equivalent) features our national animal, the beaver

A historic preservation area dedicated to the excavation and documentation of a 16th-century Basque whaling station, including several transatlantic whaling ships, Red Bay draws thousands of visitors each year (a sizable feat considering its current population of approximately 150 and remote location on the southeastern shore of Labrador). To my surprise, this park was the most challenging place to organize travel throughout my internship. It took five planes, two days, and both car and ship travel to get here (one way) from my hometown in northern Ontario. I was ecstatic to be sent on this “international” project, representing NPS on my home turf, and would be joining Parks Canada aboard the RV David Thompson for two weeks, as part of their regularly scheduled site assessment of several shipwrecks that were excavated in the 1980s and later reburied in situ to preserve the remaining structure.

The quiet town of Red Bay, made up of a few hundred people with homes scattered along the shoreline

RV ‘David Thompson’, a mid-shore scientific research and survey vessel, used for underwater archaeology work with Parks Canada (including the surveys of HMS ‘Erebus’ and HMS ‘Terror’ – two Franklin Expedition ships lost in Northern Canadian waters).

Over 70 years (from the 1540s to early 1600s), over 2,500 Basque sailors, perhaps Europe’s most ancient people, crossed the Atlantic annually, from Spain and France to the Strait of Belle Isle. Here, they established a major whaling port where Right and Bowhead whales were hunted, harvested, and processed to render oil used primarily in European lamps. Over 25,000 animals were killed in these extensive efforts. Today, these whales are some of the most endangered large whale species worldwide.

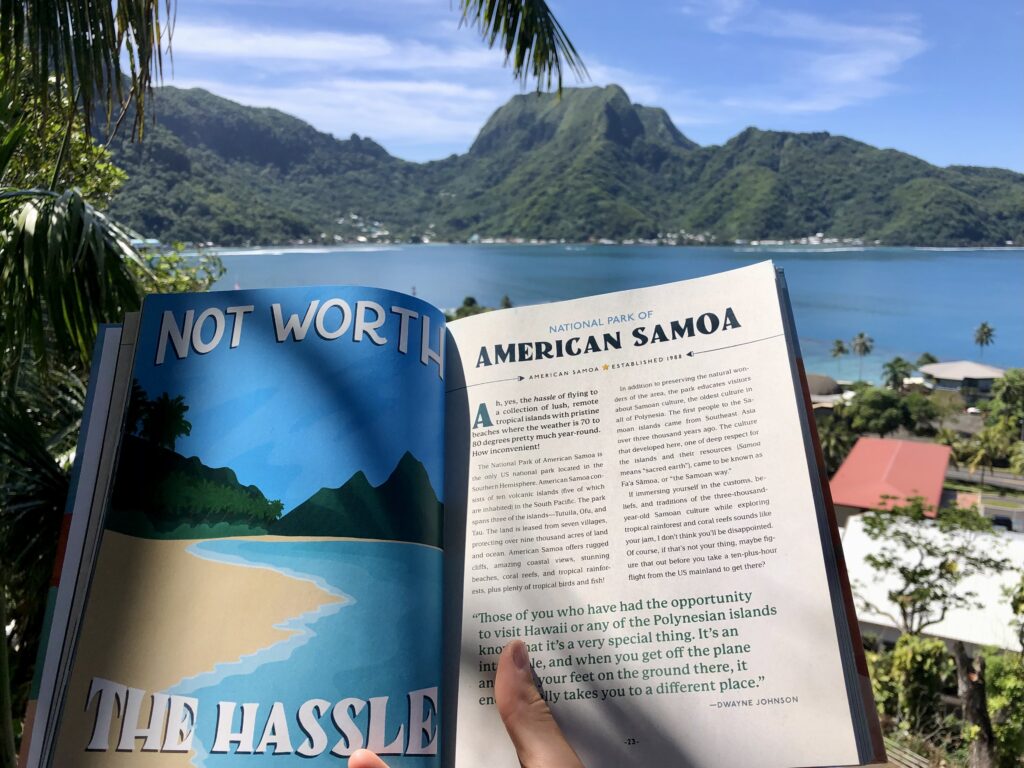

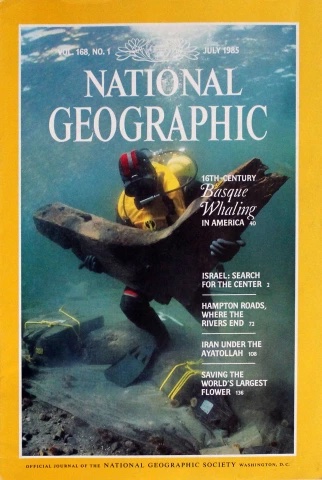

The excavation of Red Bay Basque whaling ships were carried out by Parks Canada in 1980s and was featured on the July 1985 cover of ‘National Geographic Magazine’

Well preserved remnants of Basque clothing can be seen in the town’s museum, alongside whale bones, coins, oil barrels, and timbers from the 16th century

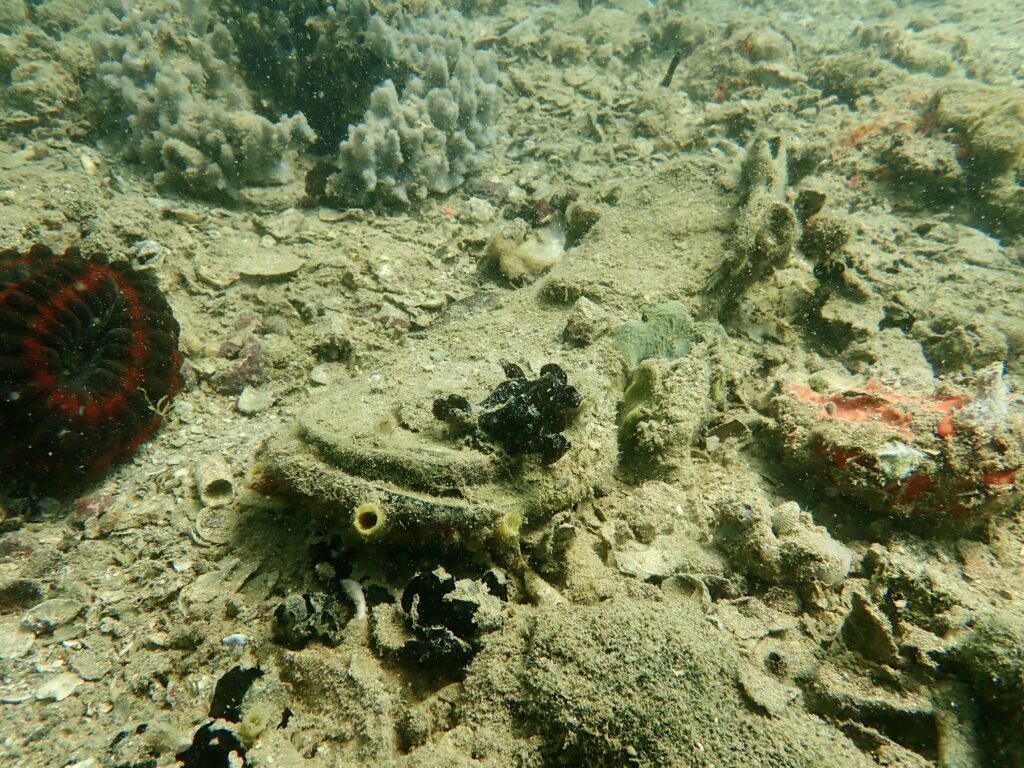

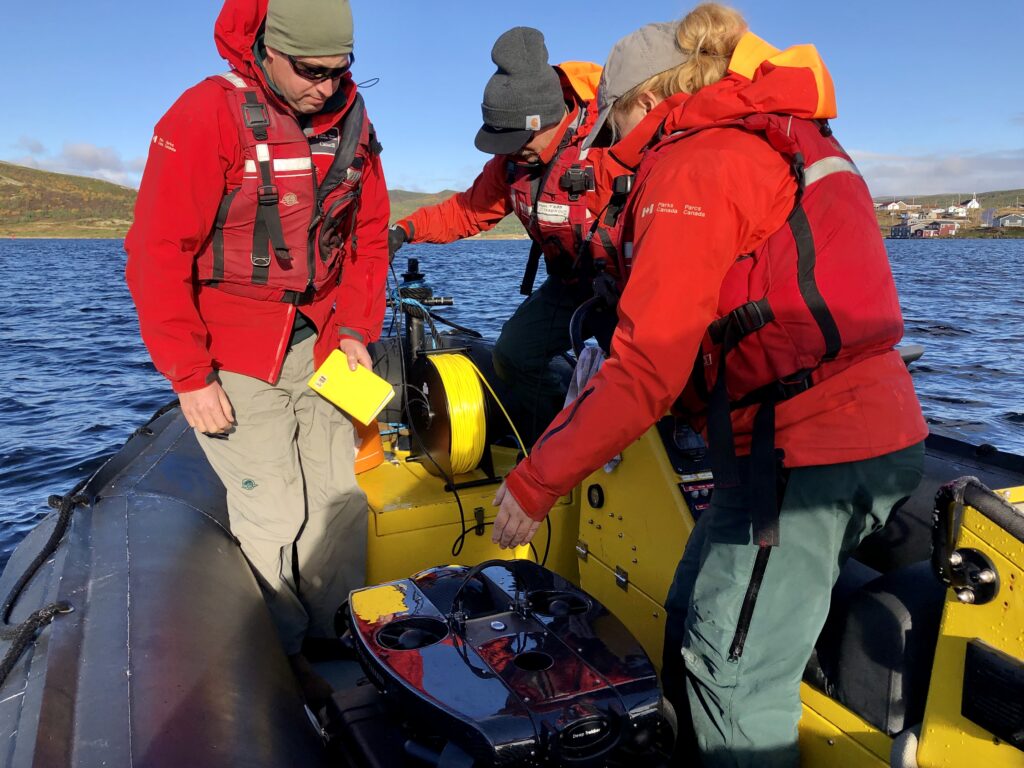

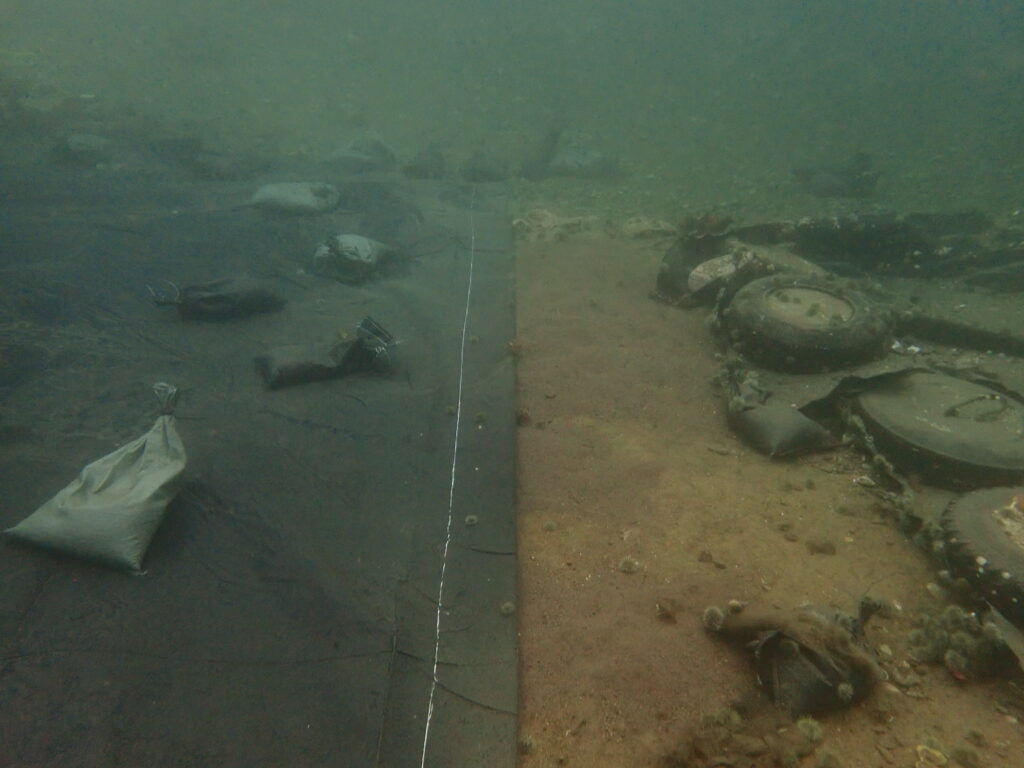

Our mission was to conduct a UNESCO-mandated 5-year site assessment, focusing our efforts on one of the most extensively studied shipwrecks in the Red Bay harbour, the well-preserved wreck of the presumed San Juan. In her prime, this 30-meter ship would have held over 70 sailors but eventually sank, in 1565, with over 1,000 barrels of whale oil on board. Underwater, we would inspect the protective tarp (laid atop the reburial mound in the 1980s), follow up with several repairs and replacements of damaged areas (repairing tears, burying exposed timbers), and ROV imaging of the current condition of the site. This was no easy feat, considering the tarps (weighing over 300 pounds each) are held down by a hundred or more sandbags and tens of heavy tires. Combined with unpredictable and likely unfavourable weather and a short-handed crew due to illness, we had our work cut out for us!

A scale model of the presumed ‘San Juan’, excavated in 1979-1985. Nowadays, Basque shipbuilders are using archaeological data to reconstruct the ‘San Juan’, using traditional methods to produce a functional, life sized replica

Preparing the protective tarp for preservation of the reburial mound which covers the remaining wreckage. At over 300 pounds each, moving and preparing the tarps is a group effort.

Remote operated vehicles (ROVs) are used to document the site, providing videos and images for future reference

The presumed ‘San Juan’ is covered by a protective tarp, secured in place with tires, sandbags, and cold tolerant zip ties. It has lasted 40 years before requiring replacement

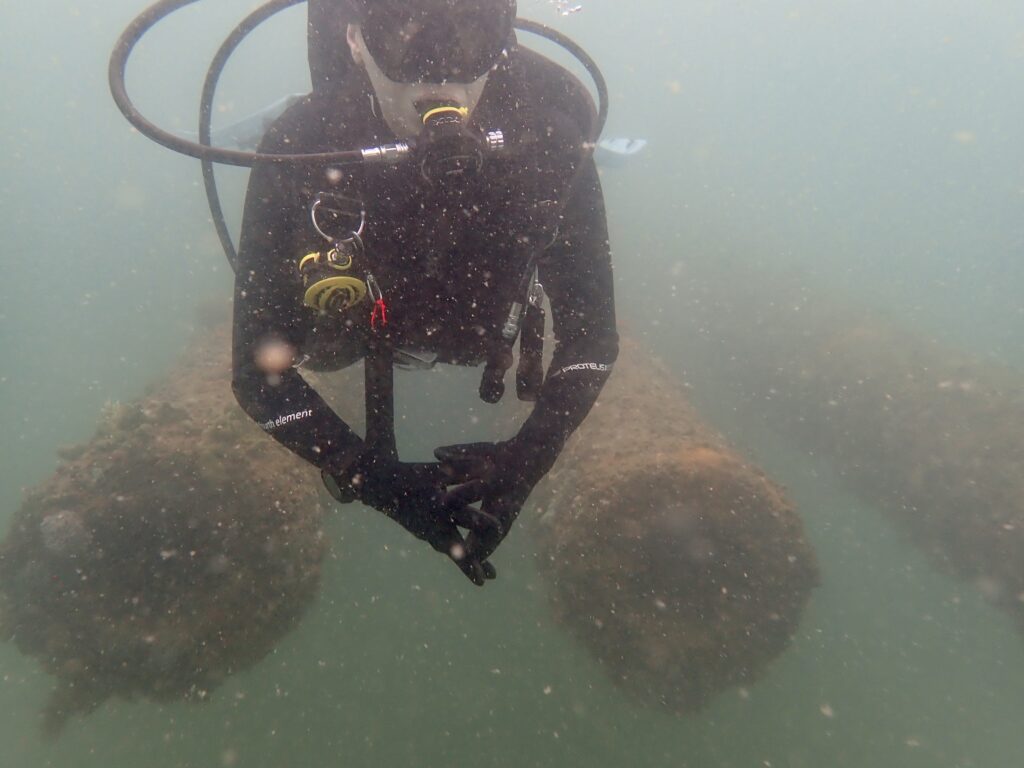

Before getting to work, I was given a general lay of the land and an introduction to the unique gear configuration used by the Parks Canada Underwater Archeology Team. The bulkiest setup and coldest water I’ve encountered to date, I was warned to anticipate -2° to +2°C seas (translating to 28° to 34°F) and more weight, tanks, and hoses than I knew what to do with. Any trepidation about water temperatures and new gear was overshadowed by my excitement to dive in increasingly extreme, unfamiliar environments and cushioned by memories of feeling invigorated and comfortable with cold water diving in the past.

A quick shore dive to try out the new gear, familiarize myself with the environment, and demonstrate several emergency drills before getting to work

Parks Canada Underwater Archeology Technician, Joe Boucher, gave me a thorough introduction to our gear, demonstrating how to assemble/disassemble/adjust/use each piece, from our full face masks to bailout and emergency air block. We do a shallow water check-out dive and I am pleasantly surprised by the water temperature at 4°C. What I do not expect, though, or at least underestimate, is how exceedingly frustrating it is to be donning and doffing a full face mask, pulling and pushing the small adjustment tabs that secure the mask in place…while wearing bulky three finger “lobster” gloves. Fine motor skills and cold water mix poorly at the best of times, and I spend several minutes underwater trying to replace and reseal the mask properly. Finally, I find myself searching for alternatives to adjust the awkward back strap and try adopting the “full fist” approach, levering my knuckle under the tab until it releases with greater ease. A sign of relief comes, and I finish feeling confident and ready for the days of work ahead.

Getting ready for dives is also often a group effort, connecting underwater communication wires, checking air, and securing gear before diving in. Underwater Archeolgist John Ratcliffe (thanks!) connecting my communication line.

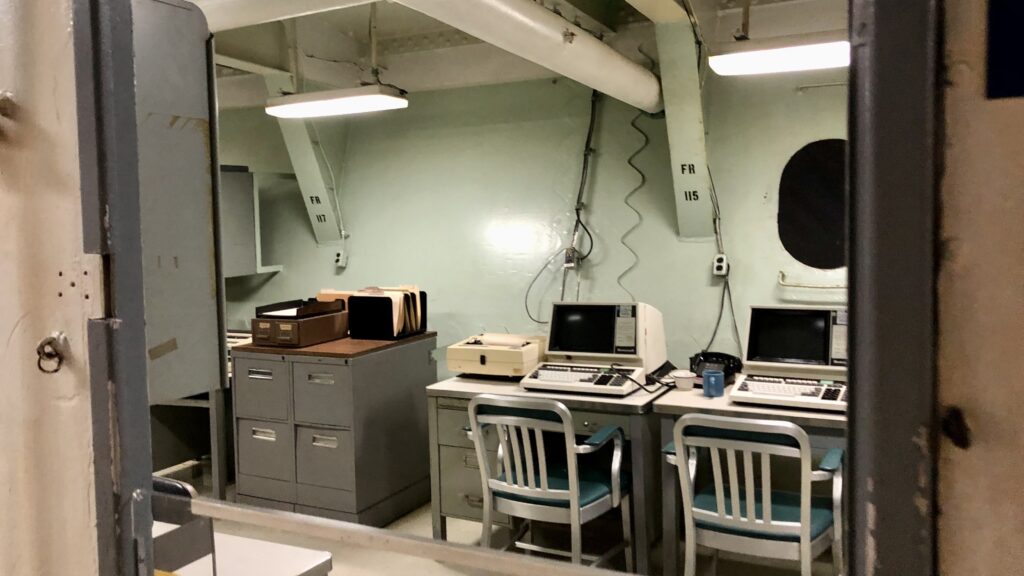

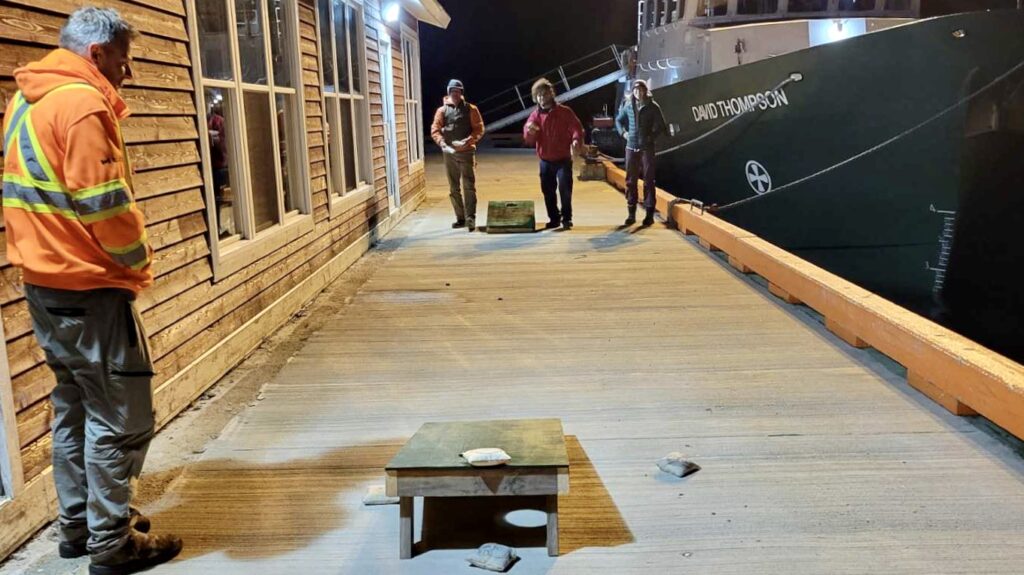

My first time aboard a large research vessel, the captain and First Mate of the RV David Thompson, Simon and Dave, showed me the ins and outs of ship life, from the galley (and, more importantly, the snack cupboards) to the engine room and emergency protocols. I quickly became accustomed to ship life, although I didn’t get a chance to test my sea legs (since we were firmly anchored within the shelter of Red Bay and the local wharf for most of the project). On board, the field team is in excellent hands, with the kind, experienced, welcoming, and friendly crew keeping us well-fed and entertained over group dinners – sharing stories about ship time around the world and memories from home. I have to admit, it is nice to be back on Canadian soil for a moment, to share stories of places we all know and love (and not have to Google the locations and names of cities/landmarks that come up in casual conversation as I sometimes did while in the US). On occasions, after a day in the field, we are treated to a spectacular Thanksgiving dinner (Canadian Thanksgiving is the second Monday of October), homemade corn hole tournaments, visits to the museum, and spontaneous hikes, keeping evenings lively even after long days.

Tying off at the wharf gives us a greater working space, rolling up 25 m tarps, filling tanks, sorting gear, and prepping for field work

Enjoying a game of corn hole during evenings, custom made by Brandon (energetic and all around jokester Deck Hand), affixed with Parks Canada logos and all

An absolutely fantastic Thanksgiving dinner put together by the ships chef, Jim, and an opportunity to get the entire ship together for a shared meal. One of my favourite evenings of the project

Walking around Saddle Island – the home base for Basque whaling operations, containing a number of former tryworks sites, cooperages, broken ceramic roofing tiles (indicating the locations of Basque buildings), and a cemetery.

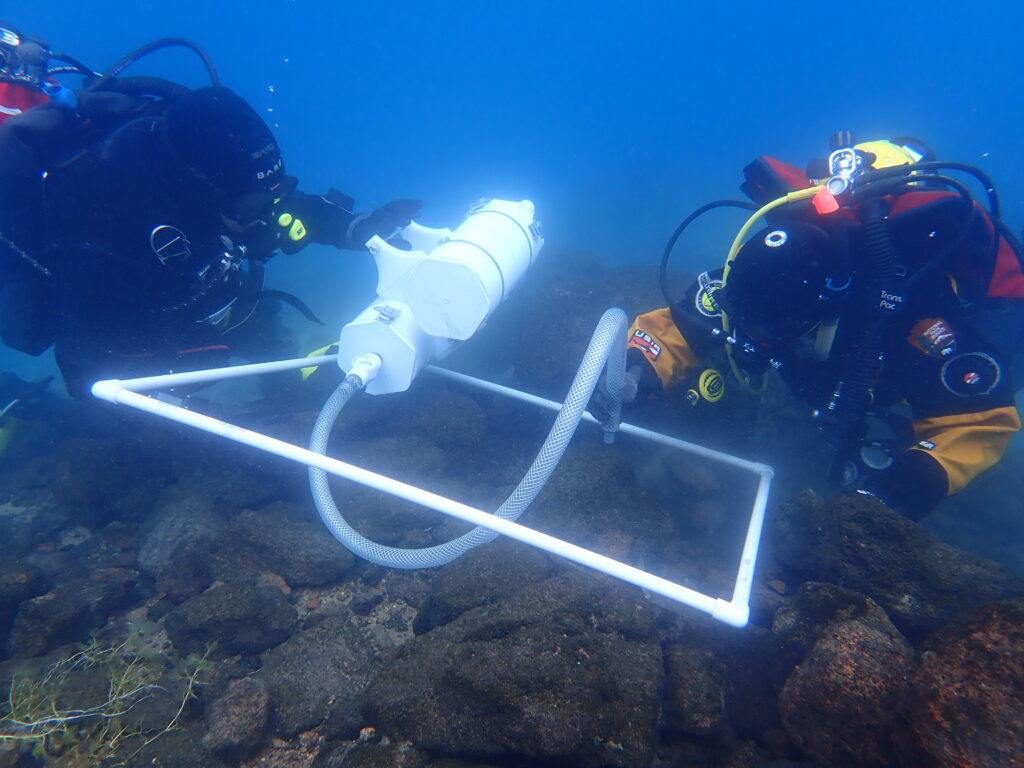

Physically demanding work, we prepare the heavy tarps, fill sandbags, prep gear, and lower it all to the site. Once we lay eyes underwater, we are struck by damage that is beyond that of previous reports. We must continually pivot, improvise, and brainstorm new ways to complete and prioritize the tasks at hand. I admire the team’s unique ability to develop a cohesive plan that incorporates the perspectives of each member, coming from various backgrounds, such as science divers, archeologists, and commercial divers. By continually calling into question, “how can we do this more efficiently, with less physical effort, and more streamline”, the project progresses over several breakthroughs in trial, error, and strategizing.  New tasks underwater require new tools, from crow bars and sandbags to steel bars and thick tarps

New tasks underwater require new tools, from crow bars and sandbags to steel bars and thick tarps

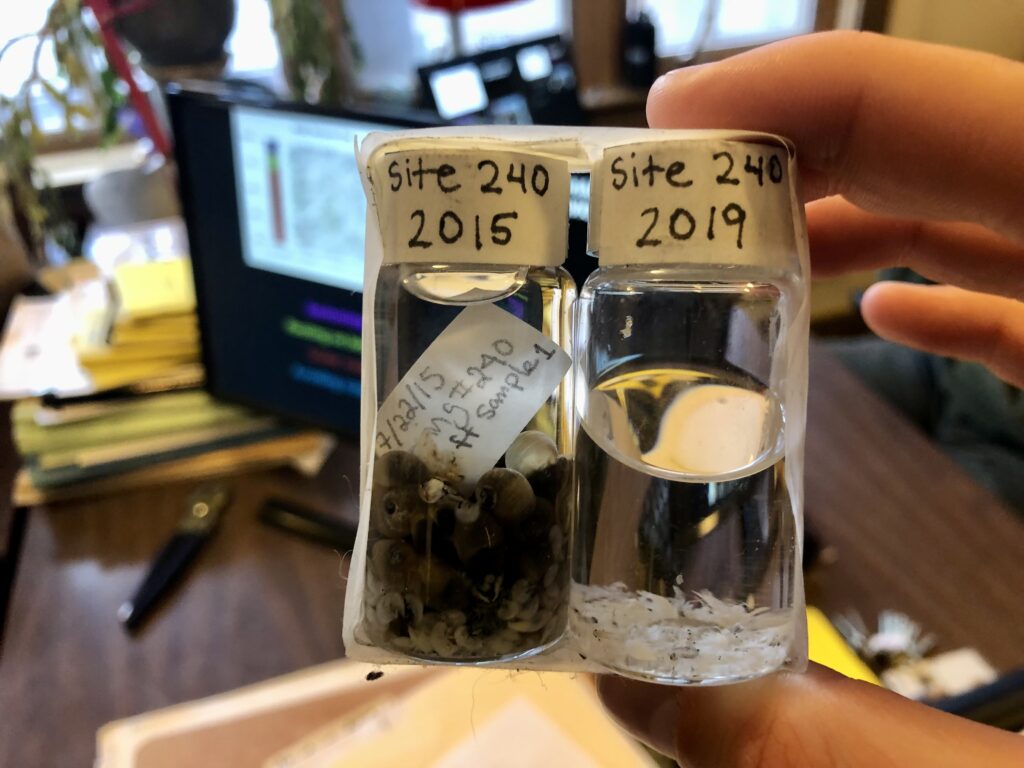

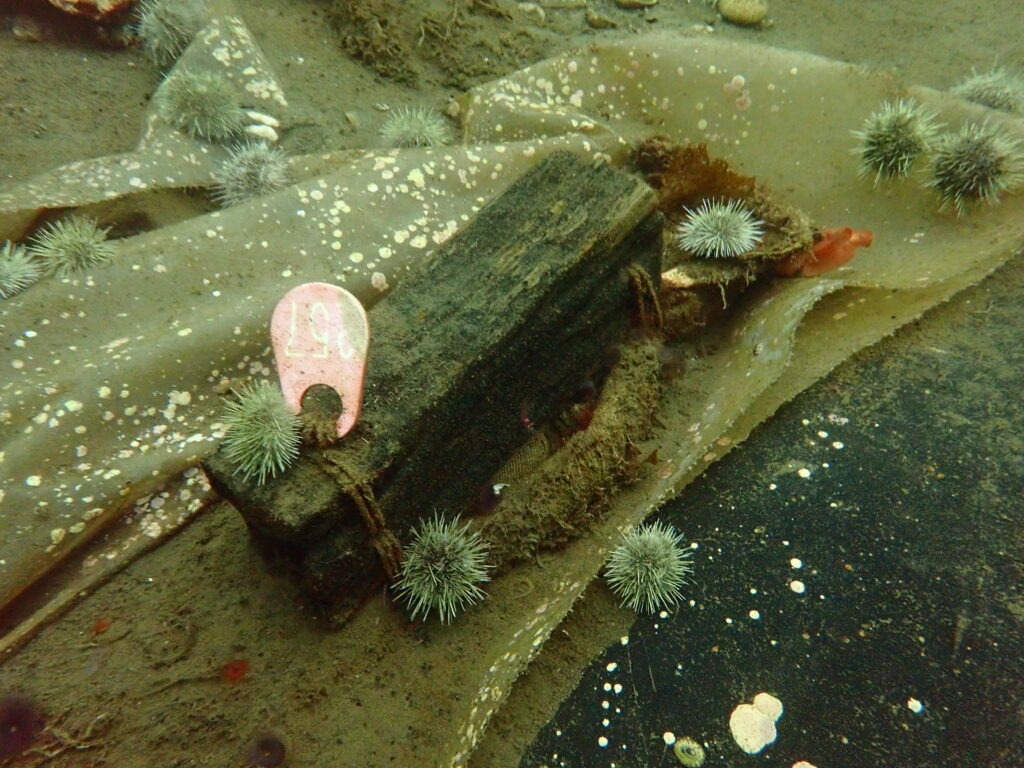

After initial excavation and reburial, several timbers from the ship were marked as samples, to track how the degradation and decay of timbers varies above and below the protective tarp.

Making progress – (right) old tarp damaged by anchors, glaciers, or weather, and (left) new tarp replacing damaged areas

Each dive brings a new task, from flipping tires and dispersing sandbags to taking photographs, documenting site condition, and rolling out new tarps. After a few days, I am excited by the growing level of comfort I have in this new environment and feel that I can effectively participate in and contribute to each task (and am also very grateful to Brandy for throwing me in the water whenever possible!). By the end of the project, I have gained many new skills and perspectives, and we are successful in stabilizing the site for further follow-up and repair next year.

The icing on the cake of a summer that could not have been any sweeter – my time in Red Bay proved to be a highlight and valuable addition to my time as the NPS Dive Program intern. Thank you, to the Parks Canada Underwater Archeology Team, for the incredibly warm welcome and the opportunity to learn from you by making space for me in this project (and also for giving me an excuse to put the “u” back in harbour and favourite after 5 months of blog writing in the US). I thoroughly enjoyed getting to know and work alongside each of you in such a uniquely beautiful, fascinating, and remote region of our country.

Of course, this excellent collaboration and internship as a whole would not be possible without the decades of impressive work done by the NPS Submerged Resource Center and NPS Dive Program (garnering a well respected international reputation) and the overwhelming support that Dave Conlin and Brett Seymour provide to the OWUSS intern each year. Thank you Dave, Brett, and the SRC team for your confidence in me and continued support. I would like to thank the growing family of NPS OWUSS alumni (made up of excellent divers, researchers, photographers, conservationists, and, now, new friends), who have connected with me, shared valuable advice, and paved the way to make my internship an overwhelming success (a.k.a made my life a whole lot easier!!), and each member of the NPS team who generously hosted me throughout the summer.

Throughout my journey, I have met many NPS employees and collaborators (thank you for following along!) that I see as role models, with exemplary skills as divers, boat operators, and team leaders (however, it is their dedication, passion for the work, and willingness to support learning opportunities for young people that shines brightest). I have seen and contributed to diving as a tool for not only resource management but also visitor protection, interpretation, training, maintenance, and facilities needs – and some of the most ‘unusual’ dives have shifted my perspective in the most impactful ways.

In truth, this is neither the beginning nor the end of my grand adventure. In part, it is a series of small steps in the exploration of self discovery, expanding comfort zones, and eagerness to learn that has brought me here. However, my perception of diving has been fundamentally changed, showing me it is feasible as a career, and giving me some of the tools I need to propel myself forward. Some of the seemingly most underrated aspects of the internship are ones that drove home the deepest shifts in my ideas of what my future goals are and what my career might look like. And that has made a lasting difference.

The Our World Underwater Scholarship Society is a web of global connections, shaped by countless volunteers and leaders in the underwater world, that has connected me to numerous organizations that I will continue to be involved with long after my time as an intern is complete. I look forward to taking more advanced tech diving courses, exploring more extreme (cold!) environments, and collaborating with new networks within The Explorer’s Club, The Women Divers Hall of Fame, and others. I share the spotlight with everyone who has contributed their time, knowledge, advice, and support on this journey and look forward to presenting this work at the 49th Annual OWUSS New York City weekend next year.