For the last two weeks of my internship, I shed the title of “scientific diver in training” and became an AAUS Scientific Diver thanks to Diana Steller, Shelby Penn, and my fellow classmates. The first week consisted of lectures on different topics including equipment, cylinders & regulators, species identification, dive emergency & rescue, diving physics, and diving physiology. After expanding our minds in the classroom, we enhanced our skills in the water. We had our checkout dives at Breakwater Cove (where I had my first cold water dive at the beginning of the internship). Then at Hopkins Marine Station, we had our first practice on Reef Check surveys.

Left image- Diana Steller demonstrating how to conduct fish transects with a 2-meter reference, Eliseo Nevarez

Right image- Tumbling tanks that has red rust on the inside. Thanks to Shelby Penn for showing me how to tumble tanks!

Reef Check helps ensure the long-term sustainability and health of rocky reefs and kelp forests along the coast of California. They monitor rocky reefs inside and outside of California’s marine protected areas. Reef Check also provides scientific data (which is collected by dedicated volunteers) needed to make knowledgeable decisions for the sustainable management and conservation. Reef Check California volunteers are divers, fishermen, kayakers, surfers, and boaters! I am so happy that I had the chance to get involved with Reef Check this summer and for anyone living in California interested in diving and conservation, please volunteer! Check out their website to learn more.

We learned species identification of fish, abalone, crabs, sea stars, slugs/snails, sea cucumbers, urchins, kelp, and other algae. As a dive team, we conducted four different surveys: algae, fish, invertebrates, and uniform point contact (UPC) using 30 meter transect tapes. For algae, we counted individuals (only if they met certain length requirements) and recorded number of stipes for two species: Feather boa and Giant kelp in an area of 2 m across the transect. We also had to keep an eye out for algae species that are invasive including Caulerpa sp., Undaria sp., Sargassum muticum, and Sargassum horneri. For invertebrates, we counted individuals (of certain lengths) and recorded sizes of abalone. For fish, our instructors and trained volunteers counted and sized the fish that they observe in an area 2 m across the transect tape and 2 m off the bottom (30 m x 2 m x 2 m). The goal of UPC is to characterize the habitat so this survey combined cover, substrate, and relief at 30 points along the transect.

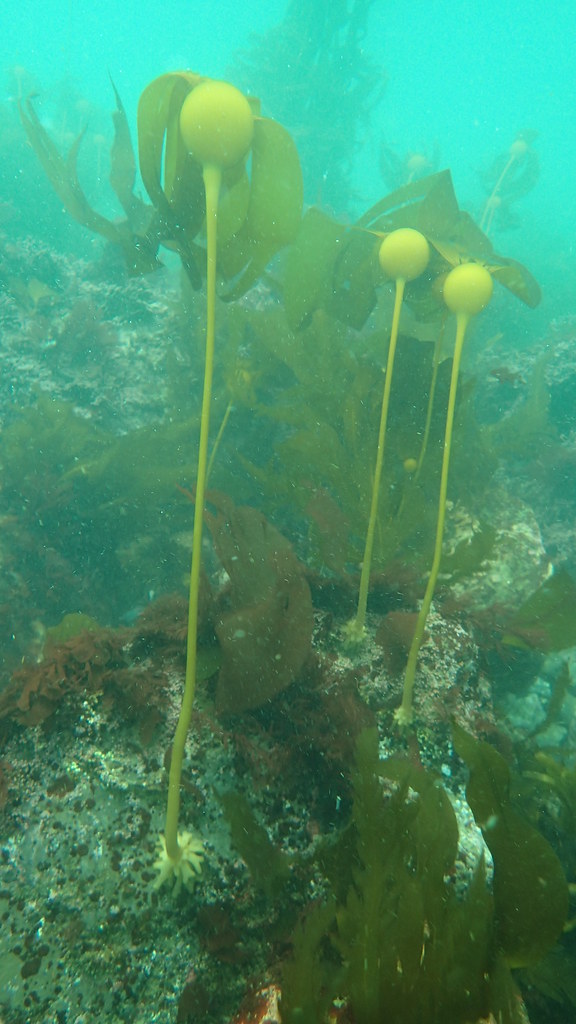

Left image- Bull kelp with other algae on a rocky reef.

Top image- All of the students moving the zodiac into the water for our deep dive.

During the second week of the diving course, we camped and practiced more Reef Check surveys at Big Creek State Marine Reserve in Big Sur, California. Big Creek is a 14.51 square mile MPA that was established September 2007. This dive site is the perfect place to obtain our AAUS certification. There was an easy beach entry, a freshwater stream nearby to rinse off our equipment, grassy area for our belongings, and super thick kelp to explore in.

Top image- Students happily rinsing off in the stream after a long dive.

Left image- View of the beach, bridge, and the mist during a break in between dives.

Right image- Our lovely compressor that we used to fill tanks while camping.

Our normal day included waking up at the camp site, preparing lunch, walking to the beach, practicing as many surveys and we could on 2 dives, rinsing off in the stream, then continuing with lectures and/or exams. On our last survey day, Dan Abbott from Reef Check came to test us on our species identification skills. We then divided into 3 teams with each diver in charge of one specific survey. Each team had two transect sites to finish and luckily, we all finished them on the last day!

Top- (Left) Beautiful view of our dive entry site and our guardian, a seagull. (Right) Normal view of our swim to the temporary transects.

Bottom- (Left) Our first snorkel/kelp crawl at Big Creek (Right) More beautiful kelp.

I couldn’t have wished for a better way to end the AAUS/OWUSS internship. This small group of people (there were only 7 students in our class) have become lifelong friends and dive buddies. From spending time every day with each other for two weeks, we all became very close and helped build one another’s skills and experience. Through difficult and hard times, we supported each other well and lifted each other’s spirits when they were low. Scuba diving is an activity where you trust your dive buddy with your life. This allowed us to build strong relationships and work together perfectly. We trusted each other to finish surveys as a team and most importantly, dive safe. We studied hard to remember the species we needed to know to conduct surveys and we quizzed each other until we all felt comfortable and confident.

Left- Group photo of our wonderful AAUS class + Dan Abbott from Reef Check.

Middle- Fellow student, Lauren Strope, loving the kelp, water, and sun.

Right- Some locals welcoming us back to Moss Landing the day we returned.

Deepest thanks to Diana Steller, without her there is no way I would’ve obtained four diving certifications, completed Reef Check training, helped on multiple research projects in California and Mexico, and had the time of my life this summer. I’ve learned many lessons about marine science, diving, and life from Diana. Thank you to the people from Moss Landing Marine Labs, San Diego State University, and those who participated in the AAUS Scientific Diving Course for the adventures, shared laughter, and teaching me how to be a better diver, researcher, and person. I can’t wait to see the success of future OWUSS/AAUS interns and to follow in the footsteps of past researchers and scientists. Although this is my final chapter as the OWUSS and AAUS intern, I am looking forward to dive deeper into marine science in the future.

A team (Chase McCoy, Shelby Penn, myself, Diana Steller, Mariana Kneppers) after our last dive at Big Creek.

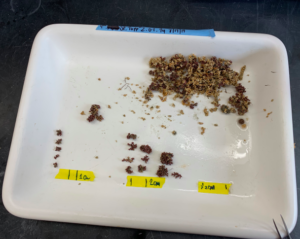

Tanks for seaweed at MLML Aquaculture Facility

Tanks for seaweed at MLML Aquaculture Facility