After saying my goodbyes to the good folks at BISC, I jumped on a plane and headed into the heart of the Caribbean, the US Virgin Islands. After landing on the island of St. Thomas, I was met byMikey Kent, the Virgin Islands National Park’s Park Diving Officer. We headed over to the island of St. John via ferry and headed up to the Biosphere, VIIS’s HQ. Because I had arrived on a Friday afternoon, we had the weekend ahead of us before starting work on Monday. I happened to land during the final few days of Carnival, the Caribbean’s summer celebration. Let’s just say that when Monday rolled around I was ready to get to work.

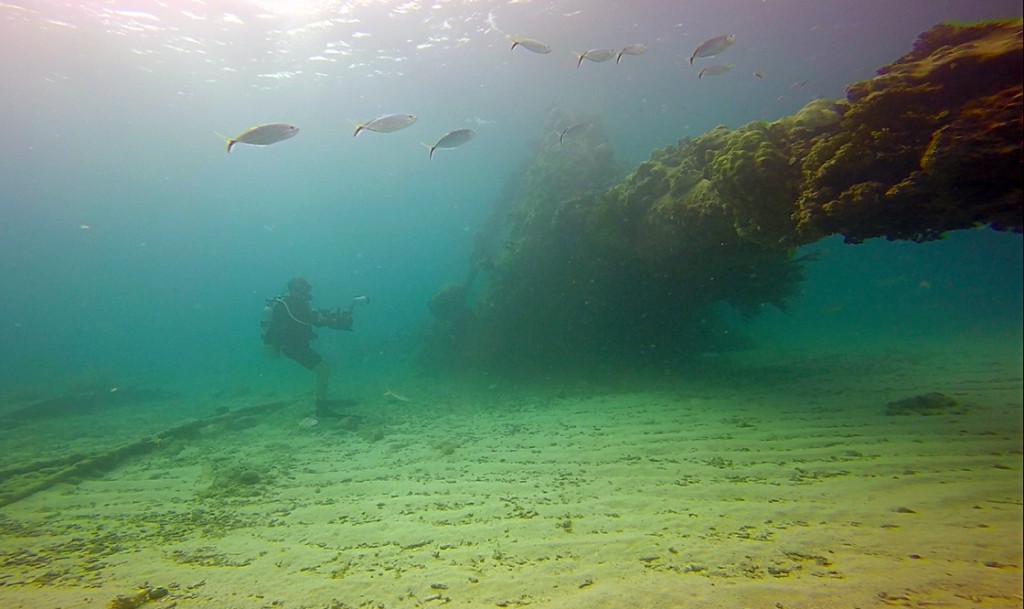

Escaping the heat on land, I dove in the Park’s cerulean water every chance I could.

The Virgin Islands National Park covers nearly 60% of the island of St. John, but the majority of the Park actually encompasses the outlying marine area as well. Because of the island’s prime location, thousands of visitors are drawn the Park’s waters each year. And the marine crew here at VIIS has their work cut out for them. If you’ve ever camped in a National Park, you’re probably familiar with an “iron ranger”, also known as a fee station.

The majority of the visitors to VIIS arrive on private boats. In order to accommodate these visitors, the Park Service maintains hundreds of moorings. If you want to spend the night, you’ve got to register with a floating ranger.

Because the majority of the Park covers the water, the Park Service has hundreds of boat moorings scattered across the island of St John. Located in sheltered coves along the shore of the picturesque island, visitors can tie up their boats for the night if they register with a floating iron ranger. However, these buoys need regular maintenance, and that’s where the Park Service comes in.

During my first day at VIIS Mikey took me on a tour of the Park’s facilities, which are starkly similar to the ones in American Samoa. We also get a chance to dive in the Park, which was a refreshing after 4 days of being dry. However, after a fun day of exploring and orienting, it was time to get down to business.

Though not as big of an issue in the USVI, lionfish have spread from South Florida to Belize. On one of our orientation dives Mikey and I found and dispatched a pair of lionfish.

On my second day at VIIS I was invited to participate on an 8-hour commercial diving instruction session. All of the diving I have done with the Park thus far has fallen under the Scientific Diving standard, which is exempt from OSHA’s commercial standards, while still being in compliance. However, the maintenance of VIIS’s buoy and ATON (aids to navigation) arrays fall under OSHA’s commercial diving standards. The Park wanted to step up a few of its divers, and I got a chance to expand my knowledge.

There are a lot of different rules regarding commercial diving, and I won’t bore you with the details. The key difference between a standard science dive and a commercial dive is the amount of people you need. In order to execute a dive safely you always need a buddy when in the water, so essentially the smallest science dive team could just be two divers. For commercial diving you need three people; a diver, a tender and a designated person in charge. The diver is the one on SCUBA executing the task, the tender sits on the surface tending a line connected to the diver, and the designated person in charge (DPIC) is running the topside show.

A veteran of the VIIS aquatic team, Devin demonstrates how the moorings are connected from the surface to the substrate. Take a good look now, because underwater every surface will be covered in some sort of organism.

The diver, connected by a tether, technically has a buddy, the tender, who feeds out line or pulls it back in depending on the scenario. If the line is too tight it will prevent the diver from doing his/her job. If there is too much slack out then the diver is at risk of getting entangled. The tender is also in charge of communicating with the diver. Two pulls mean everything is OK, three means I need something and four means get me out of here! The DPIC is usually the person with the most experience for that particular task. He/she knows ever aspect of the dive, and can anticipate any issues the diver might encounter. For example, if the diver gives three pulls on the line, they might be asking for a tool and the DPIC should know which tool they need. Also, as an added safety precaution, the diver has to always carry a “pony bottle” (a very small scuba tank) strapped to his/her main tank with an independent regulator, just in case. Remember, there is only one diver in the water so if you run out of air you’re really on your own. The tender is always ready, with gear configured, to jump in the water as a safety diver in case of emergencies.

After a half-day in the classroom, we headed out onto the Park’s waters to learn about the different mooring configurations and to get a little in-water experience. After working on equipment with the Park Service in Glen Canyon I thought messing with shackles and pry-bars underwater would be easy. I should have known better; seawater and metal are quite reactive underwater. Plus, the mooring lines are invariably covered in fouling organisms such as algae, razor clams and fire coral. After nearly digging myself into the sand trying to pry a shackle loose, I definitely have a lot more respect for the aquatic crew at VIIS. Though they’re mostly biotechs, they maintain over 200 moorings across the Park. Oh, and there are only three full time divers by the way.

Dave, a law enforcement ranger, occasionally with the biotechs from time to time. Amidst the chaos of the disturbed bottom, Dave wrestles with a shackle on the underside of a mooring.

On day three I was officially stepped up to participate on some working dives with VIIS. I jumped in the water with one of the biotechs to retrieve a mooring ball that had been hit by a boat and sank. We had to use a 50lb lift bag, which was a lot of work. After that, I spent the rest of the day switching off as either a tender or a diver. Commercial diving is definitely a far cry from science diving, and by the end of the day I was exhausted. But that’s just another day for the crew at VIIS.

Biotech Adam helps keep the lift bag’s position in the water column. After dropping down the mooring line into 50ft of water, we had to find the unattached mooring ball and bring it back to the surface.

On day four, Mikey and I switched things up a little. The Virgin Islands has a plethora of natural and cultural resources, and I was fortunate enough to join the Park’s archeologist, Ken Wild, for a day of cultural resource diving. My background in marine ecology didn’t lend itself to underwater archeology, but it was really great to see another aspect of underwater science. Ken has had a lifetime of experience in the Atlantic and Caribbean, just being on the boat with him it was hard not to absorb some of the history from the surrounding area. We checked out some anomalies from a historic site around St. Thomas, and then investigated a shipwreck that Ken found in the shallows right around the corner from the Biosphere.

Sitting in about 8ft of water inside the Park boundary, the anchor has been resting on the bottom for at least 150 years.

-

-

Part of underwater archeology requires the use of handheld metal detectors. After doing magnetometer on the surface, divers hone in on interesting artifacts in the water, if they can find them. This was my first time using a metal detector; it was really neat to watch the needle jump as I swam over metal objects.

-

-

Park archaeologist Ken Wild photographs an anomaly off of Hassel Island, near St. Thomas.

If my week wasn’t interesting enough, on day 5 I jumped in the water with VIIS’s biologist, Thomas Kelley. Thomas is another titan in the Caribbean, and together we explored a few of the Park’s more interesting reefs. Thomas was preparing for next week’s big coral reef research foray, NPS/NOAA’s biennial Fish Blitz. Much like diving with Ken, while diving with Thomas I absorbed a lot of information regarding the natural resources VIIS has to offer.

-

-

Mike Feeley, from the South Florida Caribbean Network, came down from Florida to help out with the Fish Blitz. Here Mike is taking a line point index across the transect.

-

-

Thomas Kelley, VIIS’s biologist, swims a transect at Lind Point taking fish diversity and abundance data.

-

-

Not all of the randomly generated sites are particularly interesting. However, it is incredibly important to collect data across all sites. Here NOAA biologist Mark Manaco collects fish data, while Mikey takes substrate data.

Over the weekend Mikey kept me in the water by offering to let me dive with a local dive shop, and in return I shadowed a basic open water scuba course he was conducting. In one week I managed to dive every day. From commercial diving to cultural resource diving, natural resource diving to recreational diving and finally professional diving. But my time with VIIS wasn’t over yet! Every other year NOAA partners with the Park Service to survey the reefs around the US Virgin Islands with tremendous detail. Although I had missed the Blitz on St. Croix, I was fortunate enough to participate on the first two days on St. John.

On another site Mikey took line point index data while a NOAA intern took benthic habitat data behind him.

On Monday the ragtag group of NOAA biologists gathered at the Biosphere to shake hands with the Park Service crew, some of which had come from Florida to help out for the next two weeks. After the meet and great, and a couple of hours in the office, we headed down to the water to get the show on the road. NOAA scientists had generated dozens of GPS coordinates scattered across water from St. John to the outer edge of the territorial boundaries (the British Virgin islands are almost within swimming distance of the USVI at some places). Instead of diving known sites, we would be dropping into the unknown to sample the benthic habitat, and the diversity and abundance of fish.

The sits from the Fish Blitz range in depth from 15ft to 99ft. Here Mikey Kent takes a line point index in about 90ft of water.

The crew was split into three teams across three boats, and from the harbor we motored to our sites. On a typical Fish Blitz day each team will sample 5-6 sites; if all goes well each site will only take a team 1 dive. In order to reduce surface interval times, the teams use Nitrox instead of compressed air. However, this added a further complication because the closest Nitrox compressor is at a dive shop on St. Thomas. One boat became the dedicated tank boat; towards the end of the day we would call our dives early, round up the empties from the other boats and motor to St. Thomas to get the tanks filled. Because I was only an observer on the Fish Blitz I volunteered to help on the tank ferry.

The two days I got to participate on the Fish Blitz were very exciting, and all too familiar at the same time. Much like the Kelp Forest Monitoring project, there is an immense data set that the Fish Blitz adds to. From coral health and rugosity, to benthic habitat and fish diversity, the Blitz covers it all.

After a week and a half on St. John, it was time to pack up my bags and head over to the nearby island of St. Croix. Most of all I’d like to thank Mikey Kent for keeping me in the water every day, and for giving me a place to stay. I’d also like to thank Thomas Kelly, Jeff Miller, Ken Wild, and Alanna Smith for putting up with me. Stay loose St. John!

As lush as the tropics are above the water, the coral reefs of the US Virgin Islands are home to a fecundity of fish, invertebrate and algae species. The orange coral, Acropora palmate, is an ESA listed species. It was good to see so much of it in the Park.

Thanks for reading!