The Channel Islands. This is where I learned to love the oceans as a child. I spent a couple of summers at a marine science camp on Catalina Island, and my days were filled with snorkeling, kayaking, and classes about marine natural history. Those formative summers set me on the path to where I am today. Being back here fills me with a sense of coming full circle. In addition, these islands bear a striking resemblance to the Midriff Islands in the Gulf of California, where I spent my last few years prior to this internship, so it feels doubly like coming home.

A beautiful golden sunrise in the Channel Islands.

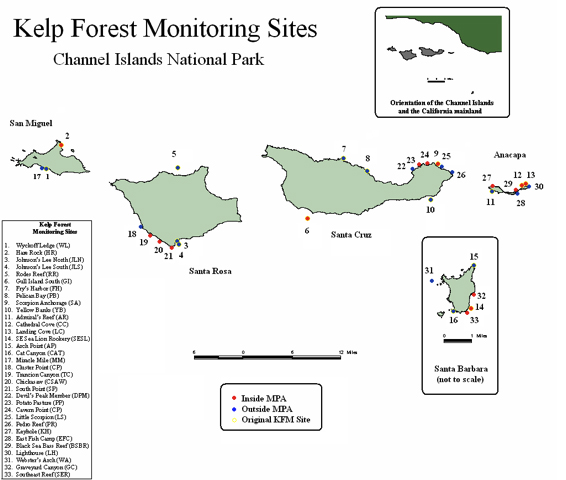

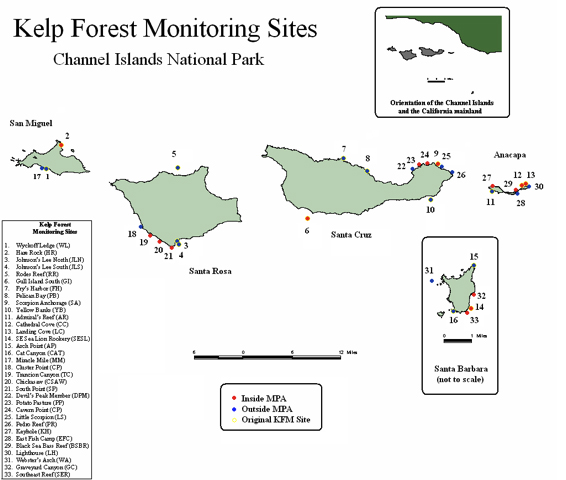

Channel Islands National Park consists of five islands, Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, San Miguel and Santa Barbara, and their surrounding waters off the coast of southern California. The park’s area is split fairly evenly between terrestrial and aquatic environments, and encompasses ~ 250,000 acres. The islands are world-renowned for their endemic species and high productivity. The marine environment is home to some of the best diving in California, with kelp forests that help support the regional populations of fish, invertebrates, seabirds, and marine mammals.

I drove down to Ventura a few Sundays ago to meet Josh Sprague, NPS biological technician, and Dave Osorio, associate biologist for CA Department of Fish and Game, on Sea Ranger II, one of the three boats run by the park. After loading up my gear and getting a good night’s sleep, I woke up on Monday morning to meet the rest of the team as they loaded up on the boat. I met the captain, Keith Duran, and David Kushner, the marine biologist in charge of the Kelp Forest Monitoring Program, who gave me a rundown of the ongoing monitoring run by his team. The other monitoring team members included NPS biological technicians Kelly Moore, Eric Mooney, and Sonia Ibarra, and Student Conservation Association Interns Sarah Traiger and James Grunden.

We set a course for Santa Rosa Island, and spent several hours making the bumpy crossing. I have been fairly lucky this summer with conditions out on the water, and this was definitely my first foray into the Pacific in many years. I was not used to the long period swell of the open ocean!

A map of the new Kelp Forest Monitoring sites.

After battling with mild feelings of seasickness (and continually telling myself “I don’t get seasick), we arrived at our destination. I had been having some trouble with my ears so I decided to take at least today off of diving, but I was so sad about that decision after seeing the conditions out here, which were particularly good for this island. Aside from some current and mild swell, it was beautiful! I stayed onboard as shore support, and at least could enjoy the gorgeous scenery of the island and open-ocean. When the divers came up, I assisted with data recording before we motored to another spot. As the divers were down, I watched and listened to the elephant seals playing in the surf.

The crew of the Kelp Forest Monitoring Program (KFMP) comes out to the islands for five-day research cruises every other week during their summer season, May through October. This project is part of the Inventory and Monitoring (I&M) Program of the NPS, which collects natural resource data to inform park management, and is the force behind the natural resource monitoring projects. I helped with this in other parks this summer like benthic habitat monitoring in Biscayne and water quality monitoring in Crater Lake. Channel Islands National Park was one of the first parks to pilot the I&M Program in 1982, with the KFMP surveying 16 sites within the park. Eight years ago additional federal funding implemented the I&M Program on a national level, based on the successes seen in the pilot parks. Now there are 32 regional networks and more than 300 parks within the program. To date, the baseline data collected from Channel Islands National Park has resulted in the largest continuous data set within the NPS system and has been used for important resource management decisions. While the California department of Fish and Game funds research, they do not fund ongoing monitoring such as the now 30 year KFMP, so NPS data is especially valuable for determining long-term, fisheries independent trends. Even though the park provides monitoring data to the state, NPS has no jurisdiction over living resources, so it is up to the state to create sound policy based on the monitoring data and other factors. Success stories here include the use of park data to support the closure of the southern California abalone fishery after decades of over-exploitation and declines due to El Niño and disease, and implement the state’s first network of marine protected areas (MPAs). For more information about the Inventory and Monitoring Program, click here: http://science.nature.nps.gov/im/index.cfm. For more info about the Kelp Forest Monitoring Program, click here: http://science.nature.nps.gov/im/units/medn/reports/docs/resourcebriefs/MEDN_ResourceBrief_KelpForest.pdf

One of the conservation tactics enacted by the state was the establishment of 11 no-take marine reserves and two limited-take reserves within the park and its adjacent waters (which are also within a National Marine Sanctuary), after the original reserve in the park, at Anacapa Island (est. 1978), first demonstrated that preserving non-fished areas actually increased ecosystem health. The Kelp Forest Monitoring Program continues to collect data to track important long-term trends in species abundance, community composition, and other indicators of ecosystem health at 33 sites in the park, sampling over 70 marine species. A new website, http://pyrifera.marinemap.org/ , allows the public and other resource managers to view data and video transects from the past 30 years of marine monitoring at the park. Check it out!

Diving in Channel Islands National Park

The first site I dove was Trancion Canyon, at Santa Rosa Island, which was at one time in the not too distant past a dense kelp forest. While the dive was beautiful, there were only five small kelp plants in the entire plot area! Urchins have ravaged the site of its herbivorous majority. Nevertheless, there were still loads of invertibrates covering the rocks, and lots of big fish to be seen, including numerous cabezon and lingcod. This dive team tackles numerous objectives on their monitoring dives—about 10 different methodologies to monitor everything from abundance to sex composition of dozens of indicator species. There are divers laying out tapes, setting up quadrates, doing roving fish counts, measuring invertebrates, characterizing substrate, collecting samples for genetic studies, and more. They definitely have the most varied set of tasks of any of the dive teams I have worked with.

After our monitoring dives were over, Sarah and I took an opportunity to hunt for photos. Now THIS is what I call California diving! Towering kelp and tons of curious fish greeted us as we splashed in. I am fairly sure that I saw more big fish on this dive then in all the other dives I had done to date this summer, combined! They were everywhere! Lingcod, cabezon, rockfish—they abounded, unafraid of my big camera coming within inches of their faces. The kelp was healthy and thick. This site is just outside one of the marine reserves, and it shows. The theory behind reserves is that they not only protect critical habitat, but the spillover from these protected areas increases the health of the surrounding areas as well. All I could think about underwater though was how much I had missed being in these underwater forests!

For the rest of the week I dove with the KFMP group at San Miguel, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, and Anacapa. Conditions were challenging, with low visibility, strong surge and surface currents, but the team still managed to collect a lot of data and I even managed to get some good images. I am so glad that I learned to use the camera in the calm, clear waters of Florida—I would have been completely overwhelmed if I had started with the camera in conditions like these!

The weather didn’t exactly cooperate for much of the trip, and by our 2nd day the winds had picked up dramatically. I struggled to hold my seasickness at bay, along with a few of the other crew members, one morning waking up at 4 am to the distinct sound of everything on the boat sliding from port to starboard and back again, and my equilibrium in a dire sate of confusion. Nevertheless, it was business as usual aboard the boat, diving all day every day, followed by data recording and ending with delicious home cooked meals every night.

Unfortunately by Thursday the weather was so rough that any chance of monitoring was out of the question—visibility was just not good enough to collect accurate data. However, we all needed to get off the boat (anything was better then sitting on the boat in that wind) so we dove anyway. Friday morning was a bit more cooperative and we finished up with some monitoring dives at Anacapa, with sea lions and seals blowing bubbles in our faces and nipping at our fins.

Diving in the Channel Islands definitely reinforced my love of California diving—it had been far too long since I had done any significant diving here and I don’t want to take another long hiatus from my native waters. The diving done by this team is the most interesting to me from all the park teams I have dived with, I think because there is such day-to-day diversity in the specific tasks they do. One dive you could be measuring sea urchins, while on the next you could be doing a video transect of the site. I definitely hope to come back and work here in the future! Thanks so much to the whole KFMP team—I had a blast working with you all!

The KFM crew from left to right: Sarah Traiger, Kieth Duran, Dave Osorio, Sonia Ibarra, James Grunden, Eric Mooney, Kelly Moore, David Kushner, and Josh Sprague.