Kelp forests are a magical place. An incredibly productive ecosystem packed full of biological life, these temperate underwater forests are an absolute delight to dive in. The image of towering kelp is what initially inspired me to pursue diving, so I was understandably excited to visit one of California’s finest kelp forest diving locations: Channel Islands National Park.

I was visiting Channel Islands to join up with their Kelp Forest Monitoring (KFM) team on one of their week-long monitoring trips. This program, which has been surveying the islands for 38 years now, is one of the longest running monitoring programs in the NPS. Visiting sites all around the five islands that make up Channel Islands National Park, the KFM team collects a huge amount of data to assess the health of this diverse ecosystem and to aid in management decisions.

The island areas closest to ports are heavily impacted by fishing activities. Despite 20% of the Park’s water being closed to fishing, sport and commercial fishing are allowed in the remainder of the Park and is the greatest impact on the marine environment there. The Park’s islands make up around 3% of the California coastline yet account for 15% of all California commercial marine fisheries landings. Unique ocean conditions mix warm and cold water currents around the islands, making them an incredibly diverse location for marine life – more than 2000 marine species live in the area. Such an abundance of life in a place so close to millions of people needs to have some type of monitoring keeping an eye on it, and that’s where the KFM team comes into play.

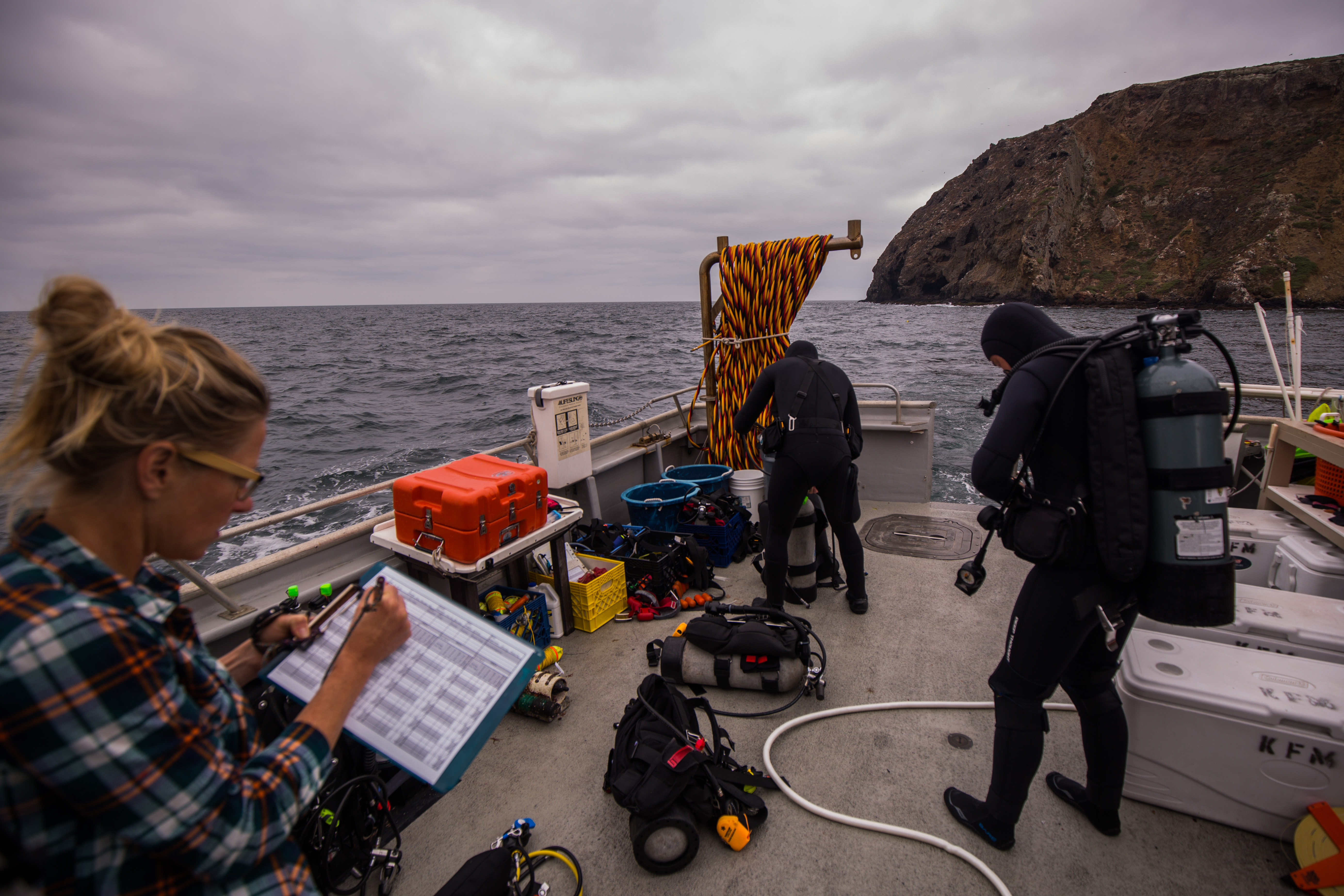

In order to effectively monitor and gather information on the complex environments, the KFM team collects a litany of data to monitor fish, invertebrates, and algae. They employ a wide array of survey types and methods, from quadrats and swaths to count individuals, to size frequency surveys and recruitment modules to learn of recruitment events and size classes, to more specialized types of data collection like plankton tows and collecting acoustic data to answer more specific questions. They utilize special techniques to be more productive underwater, like using a diver attached with surface-supplied air and communication equipment along with a surface-based tender and data recorder to allow for longer dives without the need for the diver to spend any time writing stuff down, or breathing pure oxygen from a hanging bar while on safety stops to be able to do such long and repetitive dives safely. If you can think of a type of data to collect in a kelp forest, there’s a good chance this group is doing it.

I was to join up with them for one of their week-long trips out on the water. With so many sites to survey and the relative isolation of the islands (the closest being 9 miles offshore, and the furthest 70 miles), this group does their surveying from a live-aboard research vessel – the Sea Ranger II. This 58 ft. vessel is the perfect floating research station, complete with bunks, a galley, scuba compressor, and lots of sampling gear. It has everything you’d need for a week out on the water. Working and diving from this vessel allows the team to get much more work done, staying out on the ocean all week instead of making the trip back to the mainland each evening.

I joined up with the KFM team Monday morning and before I knew it we were off to the islands. With no time to waste, we’d be going straight to our first survey site and going straight to work as soon as we’d arrived. We had a couple hour boat ride on the way out, giving me plenty of time to read up on the group’s survey protocols and to prepare myself for some cold-water diving. While I’m not a stranger to diving in chilly seas, it had been a couple months since I donned a drysuit for Isle Royale’s 36-degree waters, so I had a little bit of setup in front of me.

When we were on site and bundled up in various forms of exposure protection, we jumped off the swim step and got to work. I had done some kelp forest surveying before during my time at university, so I was put right to work on algae counts and size frequencies. Counting all individuals of certain species within 5m quadrats, I swam down the 100m transect with Joshua Sprague, a Marine Ecologist at CINP. We were counting a small selection of algae and sea star species, one of these being probably the most conspicuous resident in kelp forests, giant kelp itself. As the backbone of these forests, giant kelp creates habitat for countless species of fish and invertebrates. Certain conditions can cause rampant herbivory, often at the tube feet of spiny sea urchins, which can result in these bountiful forests being reduced to bare rock, or ‘barrens’. Unsurprisingly, some of the species that we collected a large amount of size frequency data on was the two most common species of urchin in Californian waters, the red and purple urchins. I spent a large portion of my first day swimming around plucking these living pincushions off the sea floor and chucking them into a mesh bag for topside sizing.

- An urchin barren

- A healthy kelp forest

The Kelp Forest Monitoring team does a lot of sizing of invertebrates, as a robust collection of sizes can be used to glean information of recruitment events and potentially even die-offs. Sizing, however, can take a fair amount of time. Calipers are used for precise measurements and sizes must be physically written down – which all sounds easy and quick but can really add up when you’re trying to size at least 200 urchins at each site. Additionally, time spent underwater is limited, so it must be maximized to its full extent. At sites where urchins are abundant, these inverts are sometimes brought up to the surface to be measured in order to increase efficiency. It seemed like after almost every time I returned to the back deck post-dive there was part of the team sitting out there sizing something.

In addition to the urchin size frequencies, there was a whole other source of need for sizing – artificial recruitment modules, or ARMS. These, essentially little stacks of halved cinderblocks designed to create available and desirable habitat for juvenile invertebrates, are a way for the KFM team to learn a little bit about waves of larval recruitment happening inside their park. Each year, these modules are visited, taken apart and picked clean of their invertebrate residents, brought up to the surface, sized, and then brought back down and put back away in their little artificial homes. This task was a coveted one by the team, and was described to me as the kelp forest monitoring equivalent of opening a Christmas present – you never really know what you’ll find inside. I grew to agree with them, it was always a fun surprise. Sometimes you’d get nothing but some small urchins and a what seems a couple hundred brittle stars, and other times you’d be greeted by a mother octopus and her clutch of eggs (no, we didn’t bring those up to size them as well).

Diving with the Channel Islands crew, it really was work pretty much all day long. With so much data to collect, there isn’t much time for slacking off. Even when all of the diving was over there was still more data to get – a plankton tow to complete, hydrophone recording to make, or a species list to compile. It was inspiring to see them working nonstop to gather all the information needed to thoroughly monitor these special forests.

After finishing up our site on Santa Rosa Island, we headed off to the neighboring Santa Cruz Island for our next stop. Santa Cruz, the largest of the northern Channel Islands, also has the most native vegetation – the result of a huge effort to remove introduced grazers and reestablish a natural landscape. This made for a beautiful commute, getting a chance to view these sheer sea-cliffs and the greenery that blanketed them. We also got a chance to visit a unique Santa Cruz Island feature – the Painted Cave. One of the largest sea caves in the world, this enormous cavern extends a quarter mile into the island with an opening big enough to fit a 60-ft boat into it. Keith Duran, the skilled captain of the Sea Ranger II, brought the vessel all the way into the cave to give us a close look.

Once we arrived at our new site off of Fry’s Harbor, Santa Cruz Island, we went straight to work. I was starting off with the familiar 5m quadrats, but little did I know I was in for a surprise. The previous sites were relatively easy for these quads, with only a couple species to count, but this one was a different story. A silty bottom with scattered boulders, it seemed like every exposed surface was covered in an invasive algae species called Sargassum horneri. Resigning ourselves to an a long, mind-numbing dive, my buddy Laurie Montgomery and I committed to the count, in the end reaching tallies of thousands of individuals, a task which took 75 minutes and almost all of my sanity.

Understory growth, like the ones pictured here (not Sargassum) can form dense carpets and severely complicate counts

Also while on Santa Cruz Island I got a chance to break out the camera. For most of this trip there was too much work to do to be able to take photos, but I seized an opportunity to join Rilee Sanders and Cullen Molitor as they finished up some work. As visibility was low, I opted to shoot macro, something that I haven’t gotten a chance to do much of recently, in hopes of getting some nice photos of the California morays that everyone was talking about.

- Garibaldi

- California moray

- Treefish

The next day we finished off our final site of the trip, and then went to do some logger retrievals. The KFM team has set out some acoustic loggers throughout the park and I was able to join some of the pick-up dives. In hopes of being able to use these hydrophone recordings to gauge ecosystem health, these loggers take 5-minute recordings every 15 minutes until they run out of battery or memory. Diving with Joshua Sprague and Kelly Moore, these dives were short and sweet – drop down, grab the logger, and bring it back up – but a nice way to get a quick view of some diverse sites. While doing these logger pickups, I visited my first marine protected area of the trip – a beautiful, lush kelp forest full of healthy marine life.

- Kelly Moore searching for a logger

- Josh Sprague and Kelly Moore putting a logger in a lift bag

- A healthy kelp forest inside an MPA

Channel Islands National Park is home to a network of marine protected areas. A mix of State and Federal marine reserves and conservation areas, these designations offer various forms of protections to marine life and serve as a sanctuary to preserve species diversity and abundance. In 2005, the KFM team added new sites to their protocol to survey inside and outside of these protected areas to try and gauge their effectiveness, and the results are clear. These MPAs work wonders for preserving species diversity and sizes, which allows for the maintenance of a healthy ecosystem. This is pretty clear when diving in them as well – the protected sites were among the most beautiful ones I visited on the trip, a telling testament to the importance of protection of special places.

We wrapped up our final day with some diving on Anacapa Island, the smallest of the northern islands and the closest to the mainland. This was one of the two islands out of the seven that I had never been diving on, so I was excited to check it off my list (only San Clemente Island left!). Even more exciting was that we had enough time to get a survey dive in after finishing off the last bit of work. We’d be working a couple sites around Anacapa, picking up loggers and such, and would have a little bit of free time before needing to head back to the mainland. I was able to jump into the chilly waters a couple final times and got to enjoy the beautiful kelp forests in the marine reserves off Anacapa Island for a bit before heading back home.

- Anacapa Island

- Kelly Moore takes down dive info from Josh Sprague and Katie Grady

- Anacapa Island’s famous sea arch

Shortly before leaving the Channel Islands I was met with an unexpected surprise. I was chatting with Kelly Moore, a long term KFM veteran who is about to start a new position at Kalaupapa National Historic Park. Kalaupapa NHP is one of the parks that is frequently visited by OWUSS NPS interns, but was one that I didn’t think I’d be able to visit this year due to shifting personnel and an unfortunately scrapped survey season. I mentioned this to Kelly, and was surprised when she mentioned that the fieldwork was in fact not scrapped, but still planned and was to start literally the day after I returned back from the Channel Islands. Even more exciting, she thought they could probably use an extra hand. At this point in my internship, I had no parks planned for me after CINP, so I sent out an email and before I knew it I was booking flights to Hawaii two days in advance from my phone while on a boat 50 miles offshore. With these exciting plans ahead of me, I drove straight to San Francisco as soon as I left the Channel Islands harbor in Ventura and hopped on a flight to another beautiful island chain, one a little bit more remote – the Hawaiian Islands.

Michael, Thanks for the update and your engaging narrative on the Channel Islands kelp forest monitoring project. It is difficult to find time on those trips to make good photos, but you managed that too. I appreciate your perspective, since I don’t get out there much any more.

Best wishes, Gary

Gary,

Thank you for your kind words.I’m glad you enjoyed the blog and the photos, I’m always happy to hear that they’re appreciated.

Best,

Michael