Towards the end of my internship I had the opportunity gain a good bit of experience working with underwater cameras. The aquarium camera was still out of commission from last time we used it for the rockfish survey, so Vallorie was gracious enough to allow me to use her own personal camera and housing. She spent some time with me going over the settings as well as showed me how to set up the housing and check to make sure there were not any leaks. I took the camera into the Halibut Flats exhibit to get some practice using it underwater.  I have used underwater video equipment in the past for benthic monitoring surveys, but I had no previous experience taking still shots, which I found to be much more difficult. My first few pictures came out extremely blurry, but after playing around with the lights and concentrating on steadying my hands shots began to come out clearer and crisper. After the dive, Vallorie showed me how to properly clean and take apart the housing. We took the memory card out and put it into the computer to check out my photos. As we looked over them, Vallorie asked me questions about the photos- How could this shot have been better? What would you do differently about the lighting? How could you have changed the point of view to make a more interesting background? She often teaches me by giving me minimal instruction prior to a task, allowing me to figure out how to do something, and more often how not to do something. Inevitably I make mistakes, but end up learning a lot from the errors.

I have used underwater video equipment in the past for benthic monitoring surveys, but I had no previous experience taking still shots, which I found to be much more difficult. My first few pictures came out extremely blurry, but after playing around with the lights and concentrating on steadying my hands shots began to come out clearer and crisper. After the dive, Vallorie showed me how to properly clean and take apart the housing. We took the memory card out and put it into the computer to check out my photos. As we looked over them, Vallorie asked me questions about the photos- How could this shot have been better? What would you do differently about the lighting? How could you have changed the point of view to make a more interesting background? She often teaches me by giving me minimal instruction prior to a task, allowing me to figure out how to do something, and more often how not to do something. Inevitably I make mistakes, but end up learning a lot from the errors.

On Wednesday we took the aquarium RV, Gracie Lynn, out for a collection dive; our goal was to collect Enteroctopus dofleini (giant pacific octopus) and jellyfish- in particular Aurelia (moon jellies) and Chrysaora (sea nettles). We headed south out of Yaquina Bay towards North Pinnacle, one of my favorite dive sites in this area. As we moved through the water, which was a mellow brown color because of plankton blooms, we kept our eyes pealed for jellies. Jellyfish often congregate where two water masses converge. The water masses can differ in a number of respects including salinity, density, or more commonly for this region- temperature. This time of year we often see upwelling at high spots of the reefs. Cold deep water flows inland and upon hitting the reef it is forced upward. Jellies are often found in abundance where the cold deep water meets the warmer subsurface water and are pushed to the surface by the strong upward currents. When the depth finder signaled that we were over a high point on the reef we all looked overboard to search for jellies. As suspected, we saw them congregating just below the surface. Peter, an intern from the Aquarium Science Program at Oregon Coast Community College, suited up to free dive and jumped in the water. We handed a net down to him and filled a barrel with water to hold the jellies that he would catch. I watched as he put his face in the water to watch below for specimens that were in good enough condition to put on display in the aquarium. He free dove down about 10 feet to where most of the undamaged sea nettles were hiding out. One by one he handed up sea nettles and moon jellies of varying sizes. After about half an hour, the jellies seemed to disperse, and Peter was having more difficulty catching them so we helped him aboard and continued on our way.

When we arrived at the top of the pinnacle Jim briefed us on how to best catch an octopus. The easiest method is to lay the bag behind the octopus mantle and then place your hand in front of the octopus. Using this method the octopus will back up on its own into the collection bag. I would be diving with Vallorie and my primary focus was to take photos, although if we saw an octopus we would by all means attempt to bring it up. The ocean was much calmer than last week, and the visibility, at about 7 ft., was not bad either. Due to the relatively mild conditions, Vallorie felt it was a great opportunity to load me with a few more tasks than I would normally take on. I would handle the reel, camera, and navigation. Since we would be using a safety reel tied off to the anchor line the navigation part would not be too difficult, but I still needed to get us oriented in the correct direction so we could find deeper water; I needed to reach at least 60 ft. in order for the dive to count towards my 60ft depth certification. I took a giant stride off the stern, tapped my head to signal I was ok, and reached up to grab the camera. I attached it to the D ring on my right, as I already had my octo, computer, and a reel attached to my left D ring.

When we arrived at the top of the pinnacle Jim briefed us on how to best catch an octopus. The easiest method is to lay the bag behind the octopus mantle and then place your hand in front of the octopus. Using this method the octopus will back up on its own into the collection bag. I would be diving with Vallorie and my primary focus was to take photos, although if we saw an octopus we would by all means attempt to bring it up. The ocean was much calmer than last week, and the visibility, at about 7 ft., was not bad either. Due to the relatively mild conditions, Vallorie felt it was a great opportunity to load me with a few more tasks than I would normally take on. I would handle the reel, camera, and navigation. Since we would be using a safety reel tied off to the anchor line the navigation part would not be too difficult, but I still needed to get us oriented in the correct direction so we could find deeper water; I needed to reach at least 60 ft. in order for the dive to count towards my 60ft depth certification. I took a giant stride off the stern, tapped my head to signal I was ok, and reached up to grab the camera. I attached it to the D ring on my right, as I already had my octo, computer, and a reel attached to my left D ring.

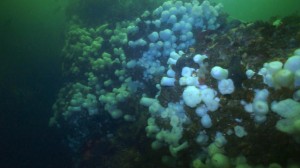

We descended along the anchor line to the top of the pinnacle, and I tied off the safety reel to the anchor line, which was a more difficult task than usual because I had to hold the camera and deal with surge. Once the line was secure, I used my compass to find East, and I signaled for us to swim in that direction. We slowly made our way along the reef, keeping our eyes peeled for octopus as I experimented with the camera, still figuring out how to orient the lights. Even with the task loading, my air consumption was better than it had been on previous off shore dives, and I could tell that I am getting used to the Pacific North West conditions. I tried to take interesting shots and get as close as possible to each subject in order to capture as much detail as possible.

Back aboard Gracie Lynn, we were excited to find that Jenna and Brittany had already brought up one octopus- a cute little fellow, about 20 lbs. Jim and Peter geared up and got in the water to try their hand in octopus catching. They resurfaced about half an hour later with a great catch. They managed to get a fairly large 45 lb octopus! We put it in one of the totes and covered the lid so that it wouldn’t feel too uncomfortable. It was a very successful day; we came back with not one, but two octopus, 10 jellies, and I managed to get some great photos. I am very excited to continue working on my underwater photography skills and it is wonderful to have such a great teacher! Thanks Vallorie 🙂

Back aboard Gracie Lynn, we were excited to find that Jenna and Brittany had already brought up one octopus- a cute little fellow, about 20 lbs. Jim and Peter geared up and got in the water to try their hand in octopus catching. They resurfaced about half an hour later with a great catch. They managed to get a fairly large 45 lb octopus! We put it in one of the totes and covered the lid so that it wouldn’t feel too uncomfortable. It was a very successful day; we came back with not one, but two octopus, 10 jellies, and I managed to get some great photos. I am very excited to continue working on my underwater photography skills and it is wonderful to have such a great teacher! Thanks Vallorie 🙂

We entered the water on the western bank, and made our way towards the center of the lake where the depth increases to about 45ft. As soon as we hit deeper waters I immediately wished I had an underwater camera; the crystal clear water reminded me of the tropics, minus the warm water and bustling coral reefs.

We entered the water on the western bank, and made our way towards the center of the lake where the depth increases to about 45ft. As soon as we hit deeper waters I immediately wished I had an underwater camera; the crystal clear water reminded me of the tropics, minus the warm water and bustling coral reefs.

A few days later it was time to try out our new skills in open water. Jim, Vallorie, myself and four other AAUS Scientific Divers set out on Gracie Lynn for North Reef, which was selected as one of the survey sites for the rockfish project. The first buddy team went down to place the block that we would start the survey from. Once they had it in place, they signaled their location by deploying a surface marker buoy, which cued Vallorie and I to get inthe water. We descended along the anchor line and pointed our compasses towards the heading we had taken on the surface. The visibility was only about 5 ft. but within a few minutes we were able to locate the other buddy pair waiting by the block. I clipped the transect tape to the block and we swam south along the wall to conduct the survey. Visibility was poor and the current made it a challenge to remain in proper positioning with Vallorie, but we made it to 50 meters, at which point I signaled to Vallorie that it was time to turn around. On the way back towards the block, the camera housing started beeping, signaling that a leak was detected. We quickly got back to the marker buoy and ascended to care for the camera. Once on board we washed the housing with fresh water and carefully took it apart. This should be the first step any time you suspect a leak in your underwater camera housing. We then placed the camera in a zip lock bag with desiccant pellets in hopes that it would dry out before any damage was done. We were unable to use the camera the rest of the day, but luckily this was just a training day and it was not critical that we collect data. We spent the rest of the dives working on skills such as navigation, setting up transects, and deploying surface marker buoys, and also had the chance to collect invertebrates for the aquarium. Although some may consider the low visibility, high surge water to be less than ideal diving conditions, I feel that the difficult working conditions enhance training dives. If you can successfully handle equipment and manage task loading in these conditions, you will be much better prepared for future dives no matter where they are!

A few days later it was time to try out our new skills in open water. Jim, Vallorie, myself and four other AAUS Scientific Divers set out on Gracie Lynn for North Reef, which was selected as one of the survey sites for the rockfish project. The first buddy team went down to place the block that we would start the survey from. Once they had it in place, they signaled their location by deploying a surface marker buoy, which cued Vallorie and I to get inthe water. We descended along the anchor line and pointed our compasses towards the heading we had taken on the surface. The visibility was only about 5 ft. but within a few minutes we were able to locate the other buddy pair waiting by the block. I clipped the transect tape to the block and we swam south along the wall to conduct the survey. Visibility was poor and the current made it a challenge to remain in proper positioning with Vallorie, but we made it to 50 meters, at which point I signaled to Vallorie that it was time to turn around. On the way back towards the block, the camera housing started beeping, signaling that a leak was detected. We quickly got back to the marker buoy and ascended to care for the camera. Once on board we washed the housing with fresh water and carefully took it apart. This should be the first step any time you suspect a leak in your underwater camera housing. We then placed the camera in a zip lock bag with desiccant pellets in hopes that it would dry out before any damage was done. We were unable to use the camera the rest of the day, but luckily this was just a training day and it was not critical that we collect data. We spent the rest of the dives working on skills such as navigation, setting up transects, and deploying surface marker buoys, and also had the chance to collect invertebrates for the aquarium. Although some may consider the low visibility, high surge water to be less than ideal diving conditions, I feel that the difficult working conditions enhance training dives. If you can successfully handle equipment and manage task loading in these conditions, you will be much better prepared for future dives no matter where they are!

Once we got back to the boat, I climbed aboard and helped to pull up Jim and Roy’s goodie bagswhich held an array of organisms including moonglow and Christmas tree anemones, burrowing sea cucumbers, sea lemon nudibranchs, and a chalk lined dirona, as well as hairy tritons, granular claw crabs and a sharpnose crab. We emptied everything into a barrel filled with seawater for the journey back and pulled up anchor to head back towards the bay. Back at the aquarium, some of the new organisms went to exhibits to be put on display, while others went to the education department. Many of the exhibits in the aquarium reflect Oregon coastal habitats, making local collections a key method for stocking exhibits.

Once we got back to the boat, I climbed aboard and helped to pull up Jim and Roy’s goodie bagswhich held an array of organisms including moonglow and Christmas tree anemones, burrowing sea cucumbers, sea lemon nudibranchs, and a chalk lined dirona, as well as hairy tritons, granular claw crabs and a sharpnose crab. We emptied everything into a barrel filled with seawater for the journey back and pulled up anchor to head back towards the bay. Back at the aquarium, some of the new organisms went to exhibits to be put on display, while others went to the education department. Many of the exhibits in the aquarium reflect Oregon coastal habitats, making local collections a key method for stocking exhibits.

Kirsten Grorud-Colvert, the lead scientist on the project, and I were dropped off at each buoy while the boat circled around waiting for us to complete the task. With me carrying the BINCKE, and Kirsten carrying the replacement SMURF, we approached the buoy.

Kirsten Grorud-Colvert, the lead scientist on the project, and I were dropped off at each buoy while the boat circled around waiting for us to complete the task. With me carrying the BINCKE, and Kirsten carrying the replacement SMURF, we approached the buoy. I waited for Kirsten to unclip the SMURF from the mooring line and replace it with the new SMURF. As soon as she unclipped the old SMURF I scooped it into the BINCKE and we signaled for the boat to come back and pick us up.

I waited for Kirsten to unclip the SMURF from the mooring line and replace it with the new SMURF. As soon as she unclipped the old SMURF I scooped it into the BINCKE and we signaled for the boat to come back and pick us up.

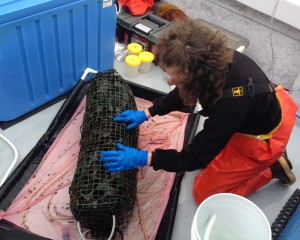

The fish were collected, and stored in individually labeled bags, which were kept on ice for transport back to the lab. The information gathered from SMURFs provides insight about settling patterns in early life stages for many nearshore fish species. This information is essential for effect marine conservation management, and will also act as a platform for educational outreach about the early life stages of marine organisms. As an efficient and low-cost method for sampling this type of information, it is hoped that SMURFs will become prevalent in large-scale monitoring projects throughout the west coast.

The fish were collected, and stored in individually labeled bags, which were kept on ice for transport back to the lab. The information gathered from SMURFs provides insight about settling patterns in early life stages for many nearshore fish species. This information is essential for effect marine conservation management, and will also act as a platform for educational outreach about the early life stages of marine organisms. As an efficient and low-cost method for sampling this type of information, it is hoped that SMURFs will become prevalent in large-scale monitoring projects throughout the west coast.