Kalaupapa National Historical Park

Kalaupapa National Historical Park

On my way to Kalaupapa, I made a pit stop in Kona on the Big Island of Hawai’i to visit my cousin, David, and his wife, Katie. Though my stay was brief, I very much enjoyed a relaxing afternoon at the beach and a morning swim at popular snorkel site Honaunau Bay (aka Two-Step) with my family. Thanks guys for welcoming me to Hawai’i and taking me in for a night! But after spending just over 24 hours in Kona it was time to make moves towards Kalaupapa National Historical Park.

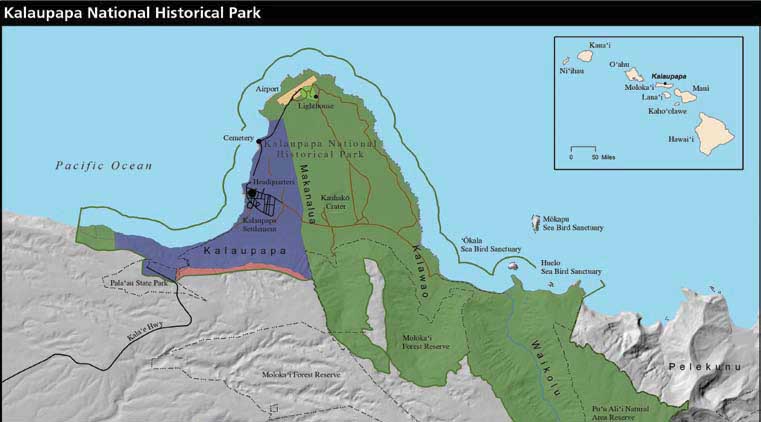

The 8-passenger, propeller plane left from Oahu just before sunrise. With just a half hour flight, we left behind the hustle and bustle of early morning Honolulu and entered a completely different realm. The park is located on the remote Kalaupapa Peninsula on the north side of the Hawaiian island of Moloka’i. Sea cliffs, the tallest in the world at over 3,000 feet, and the surrounding ocean isolate the peninsula from the rest of the island, a fact that played an important role in its history. Today, visitors to the park, like myself, must either walk down a trail along the cliff face from topside Moloka’i or fly in directly on a small, chartered plane operated by Makani Kai Airlines.

Kalaupapa National Historical Park

At the airstrip, I was greeted with an aloha by Marine Ecologist and Park Dive Officer, Eric Brown. After showing me to the historic Nurse’s quarters, my home for the next two weeks, Eric took me on a quick tour of the park, educating me on the extraordinary history of the peninsula.

In the mid-1800’s, Hansen’s disease, more commonly known as leprosy, began to sweep its way across the Hawaiian Islands. With no known cure and little knowledge of the disease itself, King Kamehameha V became fearful of the consequences of such an epidemic and exiled those afflicted with the disease to the Kalaupapa peninsula in 1865. Over the next hundred years, more than 8,000 patients with Hansen’s disease were torn away from their families and forcibly quarantined in the settlement on Kalaupapa under the Segregation Act. Early patients suffered not only from disease and the sorrow of separation, but also from food shortages, inadequate shelter, and a complete lack of medical care. Eventually, the generosity, charity, and effort of individuals, like Father Damien and Mother Marianne, brought major improvements to the lives of the patients. In the late 1940’s, the discovery of sulfone drugs brought about a cure for Hansen’s disease and the number of patients at Kalaupapa began to decrease as a result of the treatment. Finally, in 1969, the century-old Segregation Act was officially abolished.

Today, about a dozen cured patients have chosen to remain in the settlement and are allowed to come and go as they please. Here, they are continually cared for by staff from the Hawai’i Department of Health and members of their families. With a mission to preserve this solemn narrative for future generations, as well as protect the plethora of cultural and natural resources on the peninsula, Kalaupapa was established as a National Historical Park in 1980 and nowadays Park Service staff rounds out the population in the settlement at just under 100 people. As Eric’s tour progressed it became increasingly evident that the community here at Kalaupapa is extremely close-knit. Having been on the peninsula for less than an hour, Eric had already introduced me to about twenty residents! If this was any indication of how the next two weeks were going to go, I was excited to become a part of the Kalaupapa community!

Eric and I ended our tour at the Natural Resource Management Office just in time for the workday to begin. Here I was introduced to the rest of the Marine team – Maintenance Mechanic, Randall Watanuki, and Biological Science Technician, Sinefa Annandale. Together, we had a meeting to discuss the plans for my time here at Kalaupapa. This was my longest stay in a park to date and I was excited to get to experience multiple weeks of park operations at a single park. The first week of my visit, we would be finishing up the benthic marine monitoring surveys the team had started the previous week. And for the second week, visiting researchers from the University of Hawai’i were coming for a shark-tagging project! But first, there was one last freshwater site to be completed for annual water quality monitoring.

Without knowing quite what to expect, I hopped in the truck with Eric and Sinefa and we drove off to the eastern side of the peninsula. At a certain point the paved road of the settlement gave way to faint tire-tracks running through a meadow and leading up to the edge of a tropical rainforest. Machete in hand, Sinefa led the way into the dense growth. I followed behind Sinefa as he hacked away at sinewy vines and low tree branches. By far the coolest hike I’ve ever done, we trekked through the underbrush, blazing our own trail, and descended down 1,000 feet into Kauhako crater toward the freshwater lake sitting at the bottom. Though barely 300 feet across, the lake bottoms out at over 800 feet deep, making it, according to Eric, the deepest lake in the world for its surface area. As I collected and filtered water samples for lab analysis, Sinefa tested the water quality with a Sonde. The whole process only took 10 minutes and then we made our way back up the caldera walls, having to make use of ropes for the steeper parts of the ascent.

Back at the office, Eric decided to make use of the last hour or so of the workday by performing my checkout dive. While it can get repetitive to prove my skills to each new park, it is crucial that these checkout dives be performed so that the park divers are aware of my composure and comfort-level underwater and I am aware of theirs. After going over the basic mask clearing and buddy-breathing skills, we had time for a quick lap around the dock.

Kalaupapa’s underwater resources are vastly different from those I have seen so far on my trip. Large volcanic boulders scattered the reef slope, each with one or two individual coral heads growing on top. Compared to other reef communities I’ve seen where encrusting corals, sponges, or algae will fill in any and all exposed substrate on a reef, there appeared to be a considerable amount of open space just waiting to be occupied. However, while Kalaupapa’s percent coral cover and coral species diversity seemed relatively low, the community of fish that call these reefs home was vibrant and flourishing. Everywhere I looked – in the coral heads, under the rocks, up in the water column – I saw hundreds of fish. Huge schools of surgeonfish, unicornfish, and chubs swam alongside us, only to panic and swim away as a large barracuda came into view.

Over the course of the next two days, Eric, Randall, Sinefa, and I went out on the boat and completed the last remaining sites for the benthic marine monitoring program. Every year, the Marine team visits a total of 30 sites around the peninsula and gathers data on coral cover, rugosity, and fish species. On each dive, Eric would lay down the 25m transect tape and perform a fish count, while Sinefa or Randall (whoever wasn’t on the boat) would follow behind and take photographs of the substrate at every meter, which be analyzed later for percent cover data. Finally, Eric and I would round up the dive, teaming up to take a rugosity measurement.

Randall swims the transect tape taking photographs of the substrate. Eric can be seen in the distance doing his fish count. Note the vast amount of bare substrate.

However, the work week was cut short due to incoming storms Hurricane Lester and Hurrican Madeline. On Thursday, the park service and the state employees had the day off in order to prepare for the storms. In the morning, everyone gathered at the town hall to hear from the Emergency Preparedness team about what to expect for the weekend. With Lester set on a B-line for the entire Hawaiian archipelago and winds estimated to be over 100mph when it reached Moloka’i, the settlement went into lockdown mode. The trail to topside Moloka’i was closed, in addition to all flights out being suspended for the next few days. Additionally, a storm shelter was being set up in the town hall for those who experienced any damage or power outage during the storms and needed food or shelter.

Hurricane Lester’s predicted path.

With this in mind, Eric and I spent the day batting down the hatches at the office. We also moved the boat to a more secure mooring offshore and added extra lines for security. We debated moving the boat to the harbor on the other side of the island, but with the trail closed, Eric decided to play it by ear and make the decision as the storm got closer and its path became clearer.

Overnight, Madeline had stirred up the wind and dumped some heavy rains, the only damage being a small landslide and downed tree on the trail. The good news was that the Friday morning weather update showed Lester taking a more northerly route. While we were longer in the direct path, Moloka’i was placed under a Hurricane watch for high winds and rains throughout the weekend. So in anticipation of being locked up in our houses for the next two days, Tim Richmond, the Food Services Supervisor for the settlement, invited a bunch of people over for a potluck movie night. We watched Young Frankenstein as we indulged on a delicious dinner of spaghetti and Eric’s vegan meatballs. All in all, it was a fun bonding activity that made me really feel like a part of the Kalaupapa family.

Hurricane Lester veers away from the archipelago.

The weekend passed by extremely uneventfully. For all of the hectic preparations, not a drop of rain or the slightest breeze made an appearance on Saturday or Sunday. So on Sunday, the trail opened back up and activity resumed in the settlement.

That Monday, Labor Day, was relatively quite in the settlement. I was used to pool parties, fireworks, and BBQs, which is why I didn’t initially question the bonfire-esque smell coming into my room at 1:30 in the morning. But at 2:00, I rolled over and immediately knew I was in trouble. The building, not 20 yards out my window was on fire. Screaming came from the adjacent rooms and it was evident Kylie, Jake, and Susan had awoken to the blaze out their window as well. Kylie ran to sound the settlement alarm as Jake radioed it in to the park Emergency Services. Together, we all ran from our building into the street. All we could do was watch as the kitchen burned. Soon everyone from the community was outside watching with us as others from the community fought the fire from two fronts. By the time we had noticed the fire, it was too late to save the state dining hall and the majority of the effort was spent controlling the fire and preventing it from spreading to other buildings or into the open field across the street. We were extremely lucky it had rained not an hour before and the grass was still wet.

While devastating to watch, it was amazing to witness an entire community come together in the face of this disaster. Everyone helped out, whether it was turning the hydrant on or getting water bottles to the firefighters, stamping out the embers in the adjacent field or holding the high-pressure hose. Just as the sun peaked over the horizon, the last ember went out. The next 24 hours was an emotional time in the settlement as everyone tried to go back to his or her daily schedules. I have to commend all of the brave souls who helped fight the fire and supported their fellow community members through this tragedy that destroyed such a historic building and a vital cornerstone for the settlement.

After an exciting night started off my second week in Kalaupapa, two visiting researchers from the University of Hawai’i, Kosta Stamoulis and Alex Filous, flew in to continue work on a shark-tagging project. In order to track sharks, and other apex predators, acoustic transmitters are implanted into a cavity on the underside of the fish and a plastic tag is attached at the base of the dorsal fin. These transmitters emit a coded series of pings that are then picked up and recorded by acoustic receivers that are placed strategically around the reef. The array of receivers allows for the researcher to track the movement of the tagged fish as well as the time stamps of the movement. When compiled, this information can be used to identify feeding grounds, spawning sites, and habitat ranges.

Before we could get around to tagging any new fish, we had to collect the receivers and download the data from the last 6 months. We spent the next day and a half collecting receivers located all around the peninsula – even venturing over to the breathtaking eastern side of the peninsula! Some were located just offshore in a shallow, meter-deep lagoon where blacktip reef sharks have been known to hang out, while some were located 500 meters offshore at a depth of 70 feet. We were able to retrieve all but Receiver #7, which had broken off of its mooring presumably during a strong swell event and, after a 50 minute search effort, we determined that it was lost to the sea.

Once all the receivers were collected, the mornings were spent underwater redeploying the downloaded receivers and the evenings were spent on the boat fishing. This was by far the biggest fishing endeavor I have ever been on, as I’ve only ever fished in lakes, so I was a bit overwhelmed at first. We had bait rods and game rods; we were using live bait, so we had a flow-through bait tank to keep the bait alive in the back of the boat; and, not to mention, we had all of the equipment and gear to do the tagging. Baitfish seemed to be the limiting factor for all of our outings. Oftentimes it took us a while to locate the ‘opelu (mackerel scad) or akule (big-eye scad), but once we saw a huge school on the fish finder we would drop the lines, jig them up, and reel in the bait.

After stockpiling up some bait, Randall would drive us offshore a bit where Kosta and Alex would toss in their lines with the live bait thrashing about and wait. Sometimes they would bring up their lines only to find that a predator had taken a huge chunk out of the baitfish without their knowing. Other times the predators would make it known and put up a fight before somehow managing to get off the hook; they were taunting us. But by the end of the week, Alex and Kosta had reeled in four sizeable fish – unfortunately, none of them were sharks. Alex and Kosta each caught one ‘omilu (Bluefin trevally, Caranx melampygus) and one ulua (Giant trevally, Caranx ignobilis). Once they brought the fish on board, we would run a hose over the gills as they measured its size and inserted the two tags. And of course, we grabbed a picture before putting it back in the water. I didn’t catch any taggable fish. Instead my biggest accomplishment of the fishing trips was catching 3 ‘opelu on one line to save the day and allow the guys to keep fishing for a bit longer.

The day before I left, Eric came over and invited Jake, a visiting archaeologist for Cultural Resources, and I along for a monk seal survey. Beginning at the northernmost tip of the peninsula, we walked along the rocky western shoreline in the hopes of observing monk seal activity. Hawaiian monk seals are one of the most critically endangered marine mammals in the world with fewer than 1,000 individuals left in the wild. The park has been monitoring their behaviour and tagging individuals to help track the population as well as determine habitat preference and seasonal behavioural dynamics. About an hour into our walk, we spotted two subadult monk seals basking on the sandy beach. Jake and I ducked into the tree line while Eric quietly approached to observe them and identify them based on their tags. It was amazing to get to see these endangered animals up close and know that the park is doing what it can to help document their behaviour and protect their habitat. And as if the two weren’t enough, we spotted and identified another two individuals, potentially a mating pair, hanging out just up the beach!

Overall, the two weeks I spent at Kalaupapa were quite eventful. Kalaupapa is unlike any park I have been to as of yet. With a tragic narrative set at the base of majestic sea cliffs, Kalaupapa is truly a park of endurance and beauty. Its storied history has shaped the settlement into the quaint, close-knit family it is today and its isolation has helped preserve its wonderful natural resources from the vibrant fish communities to the fertile jungles. I am so grateful for having had the opportunity to experience all it has come to be.

I would like to extend a huge thank you to Eric, Randall, and Sinefa for making me an honorary member of the Kalaupapa Marine crew and allowing me to explore your beautiful park through a variety of experiences! Thanks to Kosta and Alex for imparting me with your wisdom and teaching me how to fish. And a big thank you to Tim, Jake, Kylie, Susan, Julia, Ryan, Emily, Claire, Meli, and the rest of the wonderful people at Kalaupapa who welcomed me with open arms into your community and into your family. Until next time!