For the second time this summer, I pulled up to Biscayne National Park (BISC) with my bags in tow. For the last two weeks, archaeologists from BISC, the Submerged Resources Center (SRC) and the Southeast Archaeological Center (SEAC) had been documenting two sites with the help of colleagues from East Carolina University, University of California Santa Cruz, and Cheikh Anta Diop University in Senegal.

This archaeological work would not only provide detailed maps of these two previously undocumented sites, but it also gave the NPS the opportunity to run a field school for their visiting colleagues. This work at BISC was in coordination with the Slave Wrecks Project, a program which works to research, train, and educate with a focus on the global slave trade. Collaborators of the project include Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, George Washington University Capitol Archaeological Institute, IZIKO Museums of South Africa, the South African Heritage Resources Agency, Diving with a Purpose, SRC, and SEAC.

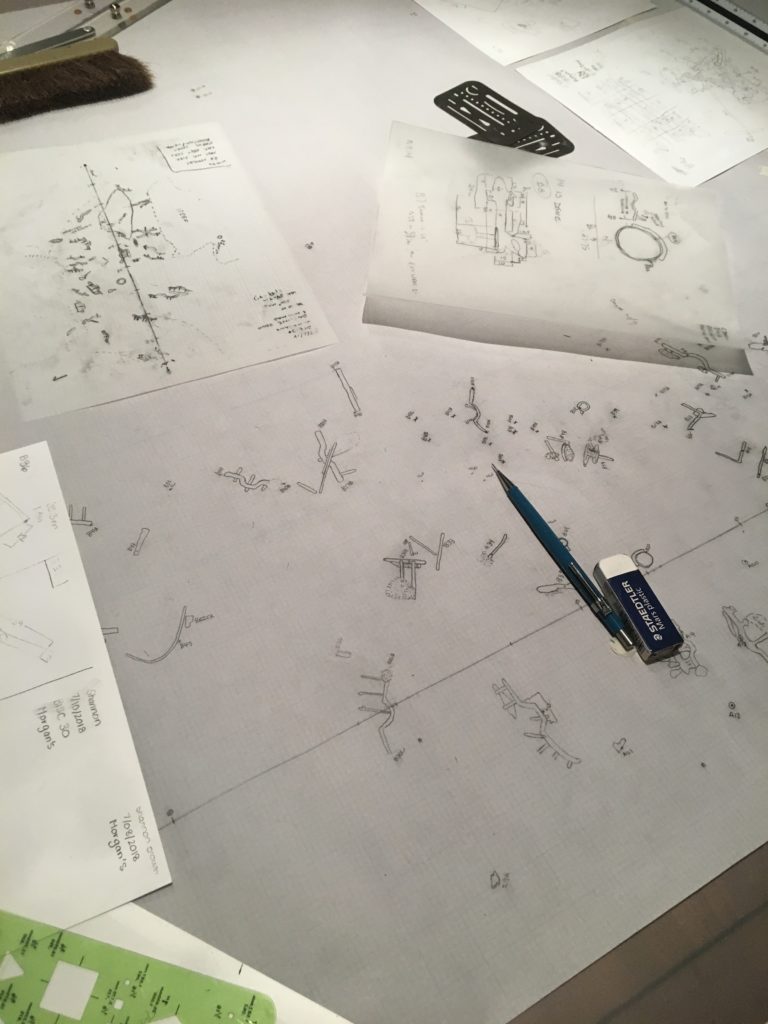

Upon arriving, I was greeted by familiar faces as I helped offload the boats. Matt Hanks, an archaeologist for the SRC and the project lead, then introduced me at the day’s debriefing. That evening, after some excellent barbeque, I observed as Joel Cook (MSc at ECU) and the three Senegalese students (Laity, Djidere, and Adama) added new drawings to the Boxcar sitemap. While observing, Joel explained the mapping procedure. For each flagged object, a mud map (i.e. a rough sketch with detailed dimension measurements) is drawn. These measurements are used on land to more accurately construct the object. Once resized, the object is transferred to mylar paper and sketched on the larger map.

Laity, Djidere, and Adama exploring the underwater world at BISC PC: Susanna Pershern

On Saturday morning, we rose early and headed to BISC to begin our day of diving. On our first dive, I accompanied Tara Van Niekerk, a Ph.D. student from ECU, as she collected some measurements at the Boxcar site. This shallow, small site was surrounded by seagrass and crowded with divers as everyone worked diligently to get their measurements. Next, we traveled to Morgan’s Wreck, the other undocumented site, where Matt gave me and all unfamiliar with the site a tour. Much larger than Boxcar, Morgan’s Wreck is located at about 30 ft and provides divers more room but also gives them more artifacts to sketch. My day ended with a trip to Pollo Tropical, a must-visit according to several members of the SRC crew.

During the surface interval, two of the Senegalese students enjoyed the stern of the Cal Cummings, the SRC’s boat

The next day, I accompanied Matt and Jessica Keller, an archaeologist for the SRC, on three dives at Morgan’s Wreck. While underwater, I assisted with measurements and got the chance to sketch my own object. Without any maritime archaeology experience, my first sketch of a simple box was awful. After each dive, I would ask Jess and Matt questions before returning to my box on the subsequent dive. Finally, by the last dive, I had adequately taken measurements from an aerial view (i.e. only width and length), and I had used a compass heading rather than angles to orient my object to the baseline. A baseline is a line that runs along the “middle” of the site and is used to orient objects at the site. The baseline is made of a strong cave line with a tape secured alongside.

A prime example of how many archaeology were working on the site at the same time PC: Susanna Pershern

On Monday, we took the opportunity to catch up on mapping and determine what drawings were missing. At each site, numbered flags were placed on each object. Therefore, we were able to determine which points were missing. Excited to draw my simple box, Charlie Sproul, an archaeologist from SEAC, explained the dimensions of the map and how I should go about transferring my object. At that moment, I realized I incorrectly measured again. To orient an object on the map, we used two types of measurements from the baseline. When objects are close to the baseline, baseline offsets are utilized. For this measurement, a tape runs from the baseline at a 90-degree angle to the object. Trilates are when two measurements are taken from a single point on the object to two separate points on the baseline. The length of the tape and location on the baseline is used to determine the position of the object relative to the baseline. Often trilateration and offset measurements are taken before an object is drawn by using the numbered flag as a measurement point; therefore, the diver sketching the object must label the location of the flag on their object…something I neglected to do.

Every evening after a long day of diving, the group works diligently to add their sketches to the sitemap

Ready to correct my drawing, I headed out with Jess, Joel, Charlie, and Arlice Marionneaux, an American Conservation Experience intern at BISC. After a day full of more diving and more measuring, I was excited that I finally had all the necessary information to add my box to the map. Over the past few days, with trial and error, I had learned a lot. I developed a massive appreciation for maritime archaeology and enjoyed assisting the group over the next few days as they worked to finish the mapping at Morgan’s Wreck.

I observed as Arlice finished up the measurements for one of her drawings PC: Susanna Pershern

In addition to our normal crew, while at BISC, we were accompanied by a team of filmmakers who were working on a slavery documentary. While their film is still in the early stages, I got the opportunity to observe document filming first hand, both above and below water. During my week, I also got the opportunity to play with my camera and capture the gorgeous organisms that populated the area around Morgan’s Wreck.

After completing a majority of the mapping, some of the group shifted their priority to jumping anomalies. Last year, in association with the Slave Wrecks project, the NPS dragged a magnetometer around a large portion of BISC’s marine habitat in search of the Guerrero, a Spanish pirate slave ship that wrecked in the Florida Keys. In 1807, Britain and the United States both passed legislation to end the slave trade; however, slavery was still legal in the United States. The heavily armed Guerrero would attack other slave ships and forcibly transfer the Africans to their boat so they could sell them for profit. In 1827, while patrolling for slave ships, the HMS Nimble, caught sight of the Guerrero. The fight ended with both ships running aground. Tragically, 41 enslaved Africans were killed when the Guerrero sunk, while hundreds of survivors were recaptured and transported to Cuba to be sold into the slave trade. For more detailed information, check out this video which was produced through a partnership between the NPS SRC and Curiosity Stream.

During their search for the Guerrero, the group identified over 1,200 anomalies. When the magnetometer was pulled across the ocean surface, the GPS coordinates were recorded when the device sensed iron. While iron can be found on wrecks, it can also be found on anchors, lobster traps, and other marine debris. To examine these anomalies, we traveled to these GPS coordinates, dropped a buoy with a weight, and then completed snorkel or diving surveys to determine what triggered the magnetometer. We spent around 10-20 min at each spot, depending on visibility. If we discovered anything of significance, a picture was taken, and a detailed description was recorded at the surface. At 1 of 12 anomalies checked on Thursday, Bert Ho, a survey archaeologist for the SRC, and I found a large piece of wood with nails. Yes, that was the most significant find out of all twelve anomalies jumped that day! While it seems trivial, jumping anomalies was awesome. Not only did you get to experience different dive sites around BISC, but there was always the small hope that you would stumble onto an undiscovered wreck.

Bert throws out the buoy to mark the anomaly’s location before snorkelers/divers enter the water

After another day of anomaly jumping and a lovely day off, I was fortunate enough to spend my Sunday with Ronnie Noonan, the 2018 OWUSS REEF Intern. Based out of Key Largo for her internship, Ronnie was able to accompany Joel, Jess, Dave Conlin, Chief of the SRC, and I as we visited several wrecks in BISC. Blessed with spectacular weather, we explored four sites along the Heritage Trail. Joel took the time to point out significant ship structures to Ronnie and I. In addition, with Ronnie’s assistance, I got the opportunity to test my fish identification skills. Having been trained to do REEF surveys in Bonaire, I was excited to try my hand in Florida waters. Not only were my fish ID skills a little rusty, but identifying fish while snorkeling made the process far more difficult.

Ronnie and I after a snorkel at the Erl King Wreck. If you look close enough, you can even see Miami’s skyline in the distance

That evening, after a lovely day on the water, I accompanied Dave, Joel, and Arlice at the welcome barbecue for Youth Diving with a Purpose (YDWP). YDWP is a nonprofit organization that works to teach students about ocean conservation and maritime archaeology. As an offshoot of Diving with a Purpose, one of their focuses is the maritime history and culture of African Americans. For the final days of my internship, I would be assisting YDWP as they ran their maritime archaeology program at BISC.

On Monday, we assisted YDWP with their archaeology coursework by setting up a mock wreck for the students to practice baseline offsets and trilates. While in Key Largo with YDWP, I was also fortunate enough to grab lunch with my friend, Lydia. She was an intern with me in Bonaire, and I was extremely excited that we got the chance to catch up. For the next two days, Arlice, Dave, Andie Dowell, Josh Marano (an archaeologist for BISC), and I traveled to an undocumented wreck in BISC and observed as the students practiced underwater mapping. With slates and tapes in hand, the students worked diligently to find objects, sketch them, and record their position at the site. In addition to helping YDWP, I worked alongside Dave to uncover artifacts with a metal detector. This site was discovered while jumping anomalies last year, and archaeologists need more information before determining whether or not the site is the Guerrero.

YDWP students swim from their boat to the site to begin mapping PC: Andie Dowell

Working with YDWP was a privilege. Not only did I meet a group of enthusiast students, but the instructors were clearly passionate about the underwater world as well. Thanks again Dave for allowing me to assist with this program for the final days of my internship!

And of course, we decided to take a group picture where all of us are looking directly into the sun

After drying my gear one last time and packing up my bag, I was ready to head home for a few days before traveling to Washington, DC. While in DC, I would present about my summer internship to various members of the National Park Service.

Thanks to the members of the SRC, SEAC, and all their colleagues who were willing to teach a biologist some archaeology. I really enjoyed my second trip to Biscayne National Park. I got to participate in a project entirely out of my realm, and I had a spectacular time!