Double-check gear. Double-check directions. Check for traffic, confirm the meeting place, and eat a hearty breakfast. My first (and only) assignment at the park begins at 0900 this morning, and I want to be fully prepared. I arrive at the Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam Pass and ID office to meet Scott Pawlowski, Chief of Cultural and Natural Resources of World War II Valor in the Pacific National Memorial – to receive my sponsored pass to the military base that houses NPS offices, dive lockers, and cultural resource collections. After a quick introduction, I can see time is of the essence (with an average of 4,000 visitors per day and the end of the fiscal year approaching, everyone’s got their hands full, even more so than usual or at other parks I’ve visited). Knowing I’ll need a form of ID to secure my pass, I ask Scott if I should use my passport instead of a driver’s license… since I am not a US citizen. I quickly realize that is the wrong question to be asking when trying to access a high-security, active US naval base. Next thing you know, we were headed straight out the door in search of Plan B. Access Denied!

I stand by during a few quick phone calls and await further instructions. A handful of nervous minutes pass, but Scott relays a new plan. After several pivots, dive operations are still a go. I meet my dive buddies, NPS diver, PERL volunteer, and 2017 OWUSS AAUS intern Erika Sawicki and NPS Interpretive Guide Billy Crowe, at the visitors center, past the tourist ferry, and through to the “employees only” gated dock. Curious eyes watch as we launch the small NPS vessel destined for one of the nation’s most important war memorials, shipwrecks, and mass graves – USS Arizona.

My first glimpse of the USS Arizona memorial from the NPS vessel

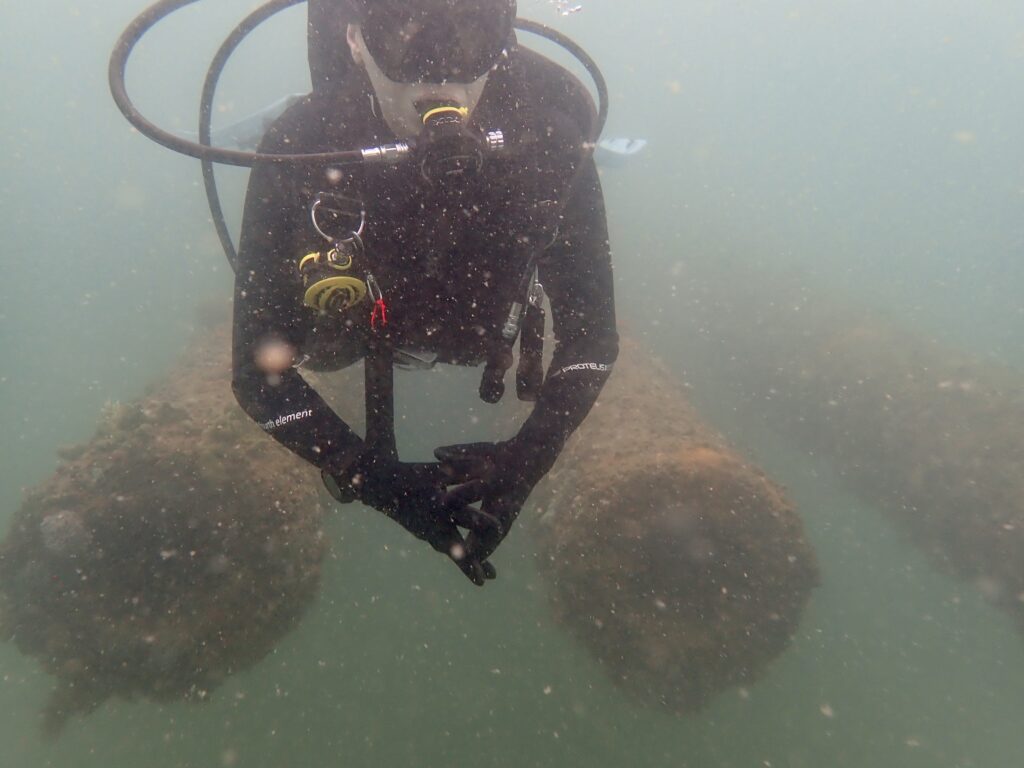

Once we arrive at the memorial, while trying to be as inconspicuous as one can possibly be with flashy gear and clanking scuba tanks, Erika and Billy set the stage for our dive. Unrolling a well-used map from his bag, Billy gives me a hushed orientation to the ship, pointing out key features, the location of artifacts, and mapping our path underwater. The anticipation builds, and we wait for the perfect moment to slip underwater during the brief break between ferry arrivals. Knowing that only a handful of individuals are trained and permitted to dive this site each year and the significance of not only the remaining wreckage but of the December 7th, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor creates an atmosphere unlike any other dive I’ve done. It makes sense – this dive is unlike any other dive I’ve ever done– or ever will do for that matter.

Moments before our dive on the USS Arizona, the memorial full of curious and contemplative visitors in the background

The attack on Pearl Harbor signaled the entry of the US into World War II. The wreckage of USS Arizona is a sacred site, home to the remains of 1,177 crew members who did not escape her fiery fate, forever buried at sea. Nowadays, dive operations are limited to preservation and documentation, in respect to those who have lost their lives and loved ones left behind in this tragedy.

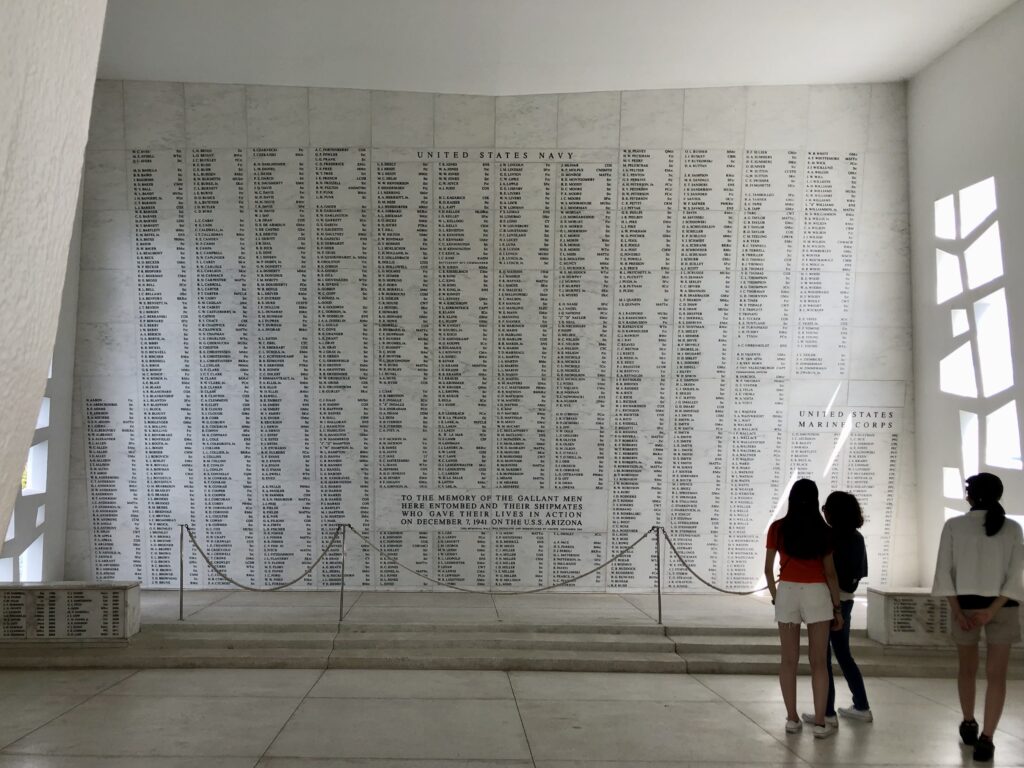

Inside the memorial, stands a list of victims during the December 7th, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor

During the start of our 90-minute dive, Erika points out a rope. Seemingly innocuous at first, I suddenly remember that this is the line that guides NPS divers during the interment of survivors who choose to return to the vessel after their passing. We descend into the empty turret, the bottom slow to emerge in limited visibility – this is one of the most powerful moments of the dive. It is here that crew members are reunited with their fallen comrades. In the more than 80 years that have passed since the attack, full lives have been lived in the wake, for the nearly 300 survivors. In the devastation of broken families, lost brothers, and national grief, USS Arizona is a place of reunion and remembrance in the present day.

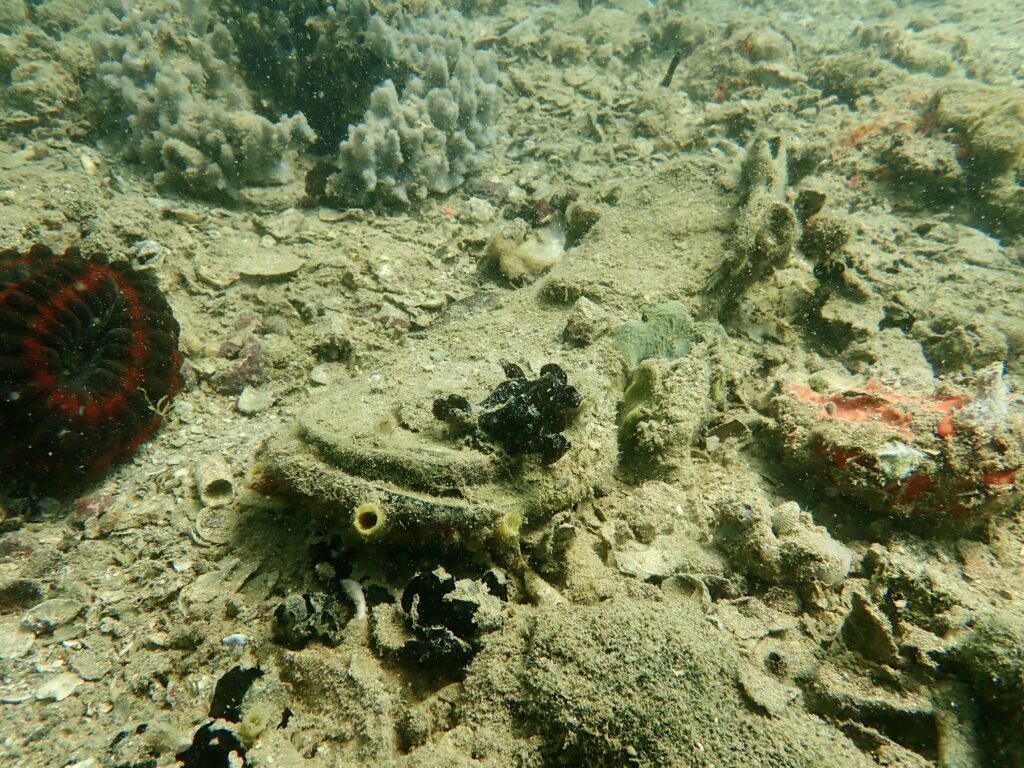

We swim past artifacts scattered aboard the ship’s deck: boots, bowls, and personal belongings frozen in time. We peer into several blown-out portholes on the side of the ship, silted furniture still sits in place, providing context and scale, and a sullen personality to her remaining structure. Having never been on a ship of this size, I find it hard to imagine what everyday life would have looked like onboard. I wonder what these rooms were used for, who they belonged to, or if personal mementos once decorated its walls. Scanning the wreck, swimming under the hundreds of visitors above only feet about us, we round the bow, peering through large holes in the vessel where the anchor chain would have been attached, illuminated with sunlight. Although present, I am surprised at how little marine life occupies the outer walls and deck of the ship (although a few fish manage to pull my attention at times before returning to the task at hand). I snap back to see Erika floating upside down, carefully positioning herself headfirst in a stairway. I follow suit once she emerges and notice small globules of oil gathered on the overhead covering – evidence of the steady stream of oil that has been leaking since the first moments of the attack. We disperse slightly and take in a few last silent moments while collecting personal items accidentally dropped overboard by tourists. We quietly tuck away into the NPS vessel upon surfacing, and slowly cruise back to the visitor’s center. Between conversation, I’m left to digest this experience, seeing first-hand what the majority of the population will only ever see through a TV screen.

Three 14 inch guns stand strong among the wreck of USS Arizona

A few remaining artifacts scatter the deck of USS Arizona, including bowls and kitchenware

The sole of a WWII era shoe sitting atop the deck

A watchful porcupine fish peering between the pillars which support the memorial directly above the ship

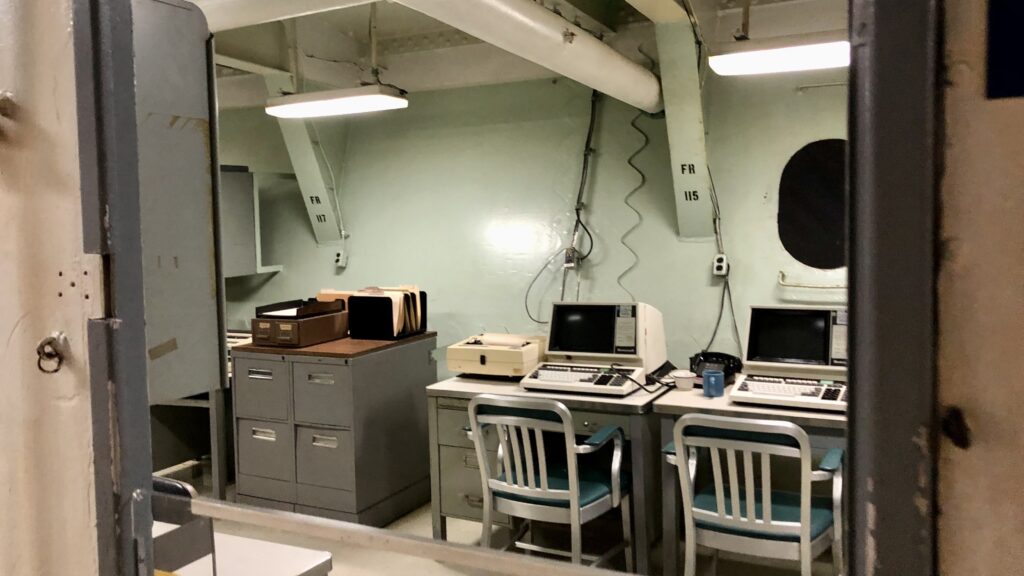

The next day, a tour of USS Missouri fills in a handful of knowledge gaps and questions I have after yesterday’s dive. For the first time during the internship, I feel like a tourist (thank you, Scott, for organizing tickets for USS Bowfin, USS Missouri, and the Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum for me). Blending in with visitors, I start the day with a walking tour of USS Missouri, which covers general boat specs (including firepower), and its role in the end of WWII as the site of the surrender ceremony of Japan on September 2nd, 1945. Now a historical museum, I am excited to explore below deck. Meandering each hallway of USS Missouri gave me a glimpse into just how well equipped and surprisingly spacious these ships were (although I’m sure no one was saying that when 3,000 crew members were on board). I walk past offices, dorm rooms, officers’ quarters, cafeterias, bakeries, dentist facilities, and post offices. In 30 minutes, I likely barely scratch the surface of the true scale of the ship; however, I quickly realize these are essentially floating cities. The well-staged rooms bring life to the ship, furnished in true mid-1900s fashion, and through this lens, I see the silt-covered, monochromatic remains of USS Arizona in a new light.

Approaching USS Missouri, now a historical museum

On deck of USS Missouri overlooking Pearl Harbor

Officers quarters below deck of USS Missouri

Undeniably a US tragedy, the impact of the attack on the American people, and Pearl Harbor had ripple a ripple effect globally. I wonder how many Canadians have ever had the chance to dive on USS Arizona? To experience history “first-hand” is a remarkable opportunity, and one that leaves a lasting impression. At Pearl Harbor National Memorial, history comes full circle, with historic vessels triggering both the beginning and the end of the US involvement in WWII side by side. The conditions of the vessels perhaps symbolic, the rusting remains of Arizona, heavy with the weight of war, and the polished Missouri leading the way forward, in peace and reconciliation.