I arrived in American Samoa, my last stop of the internship, the night of Monday, September 30th. The next morning, the federal government shut down. Forbidden to enter the park, use park boats or equipment, or even enter the park office, I had to instead enjoy a two-week vacation on this beautiful island in the South Pacific.

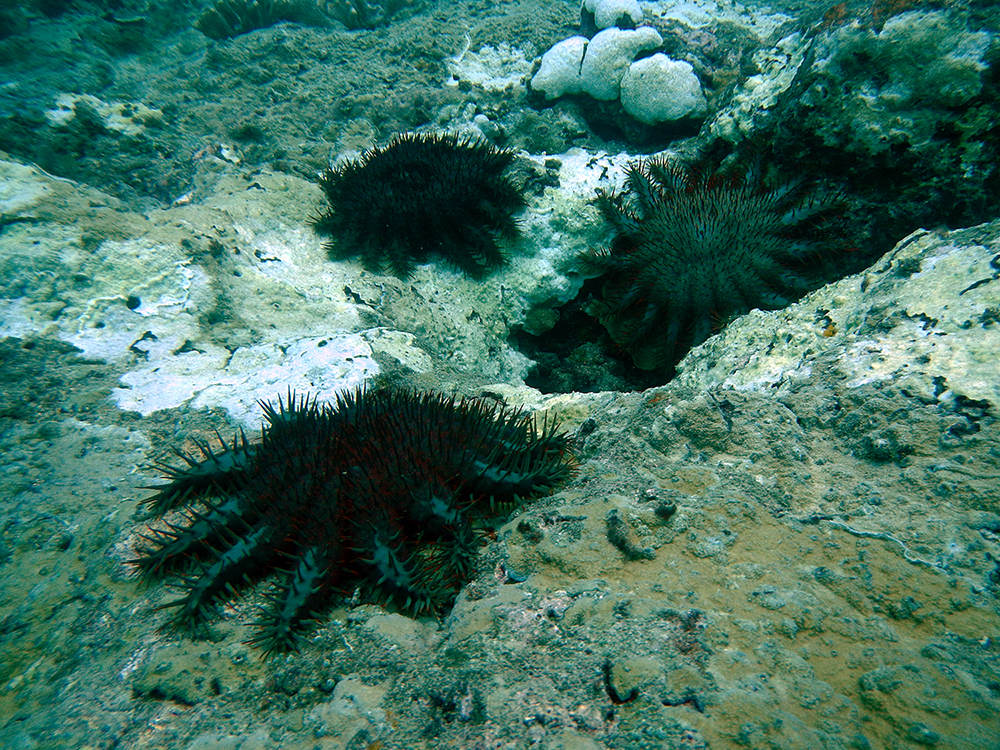

Had Congress agreed on the budget, I would have been helping the American Samoa National Park marine resources team address an outbreak of Crown of Thorns (COTs for short), coral-eating sea stars. Although native here in the Indo-Pacific, occasional population explosions can devastate coral reefs. Historical data suggests that such outbreaks occur naturally every hundred or so years, giving reefs time to recover, but recently outbreaks have occurred across the Pacific every twenty, ten, or even five years, with detrimental consequences for coral reefs already staggering under the burden of pollution, overfishing, ocean acidification, and ocean warming. I had learned about the role of COTs in “natural” destruction of coral reefs from a particularly formative episode of Kratt’s Kreatures, but it wasn’t until now that I found out that there is indeed an anthropogenic contribution to COT outbreaks. COT larvae fare best in plankton bloom conditions, which have been happening more frequently due to increased nutrient input to coastal waters from agricultural and wastewater runoff. Three or four years after a large plankton bloom, COTs reach maturity and a huge outbreak overwhelms the corals. In an attempt to rescue American Samoa’s reefs, the NPS and other natural resource agencies have been focusing on COT removal for the past several weeks. They kill them by injecting them with sodium bisulfate, which disrupts their internal pH balance. So far these agencies have killed thousands of COTs in crucial sites.

With the government shut down, all COT removal activity was put on hold. This was distressing because each day we weren’t removing COTs meant the loss of corals that could take over a hundred years to grow back (if they can recover at all, given additional stressors like warming and acidification). It’s sobering to consider that our two-week government shut down will have consequences on the scale of decades and even centuries, as far away as American Samoa.

The furlough crew made the best of the situation by reveling in the natural resources American Samoa offers outside of the national park. I stayed with NPS Marine Ecologist Tim Clark, the island’s Chief Instigator of Adventure, and merely by waking up each morning and agreeing to whatever he had planned, I managed to fill the days with hiking, snorkeling, kayaking, diving, and general island exploring.

One fun and educational excursion was a tour of the NOAA weather station. American Samoa is home to one of four baseline observatories for parameters like atmospheric carbon dioxide; its fellows are in Barrow, Alaska; Mauna Loa, Hawaii; and the South Pole. It’s from these stations that we get estimates of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, which recently made headlines when CO2 hit 400ppm. I’ve seen the Keeling Curve (link to http://keelingcurve.ucsd.edu/) in every one of my environmental science classes, but had never heard of the station in American Samoa. Station Chief Jesse Milton was still at work, so he gave us a tour of the instruments and sampling that goes on at the station.

Other highlights included kayak expeditions to explore caves and fun snorkeling sites, a game of island golf, and checking out a flying fox roost at sunset. The National Park was created largely to protect these fruit bats, the only native mammals on the island. We saw both species: Pteropus tonganus and Pteropus samoensis.

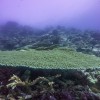

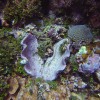

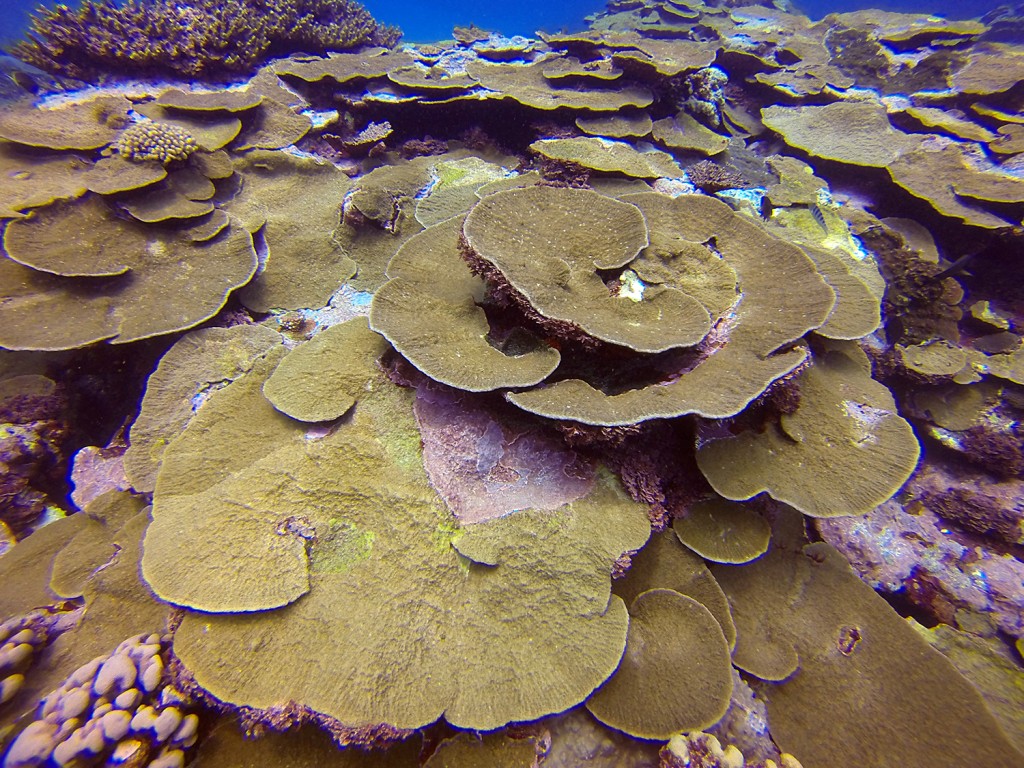

Diving in American Samoa was fantastic. This was my first time diving in the southern hemisphere, and I was thrilled to see so much coral: unbelievably diverse, and the colonies were enormous. I was also particularly excited about the giant clams and anemonefish, which I had never before seen in the wild. Our diving adventures included persuading a local ferry driver to drop us off mid-ride so we could dive around Aunu’u island (it’s not everywhere that you can book a $4 dive boat!), and diving via kayak, towing them as we drifted. Tim’s neighbor Nick Saumweber, a soil conservationist with the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, took advantage of the time off to complete his advanced open water diving certification with Tim, and I tagged along for his certification dives. I was especially eager to join the night dive, for which we left directly from the beach across the street from their front yards. We peeked at wide-eyed squirrelfish and parrotfish asleep in coral cubbies, listening for theremin echoes of whalesong.

Many thanks to Tim for hosting and entertaining me for two weeks! Thanks also to Nick Saumweber, Alice Lawrence, Wendy Cover, Mark MacDonald, Adam Miles, Christine Bucchianeri, and the rest of the Palagi crew for spending time with me, joining our adventures, and making my island furlough experience so fun and memorable.