“Don’t mind the lizards, watch out for mean dogs, and don’t drink the water. Those are my three biggest island tips,” Tori tells me as we are preparing to go to the grocery store. “I wasn’t sweating it about the lizards, but good to know about the dogs!” I respond. Tutuila, the main island of American Samoa has a rash of stray dogs. As cute as they may look (they generally do not look cute), they are wild animals and fairly ferocious.

Tori picked me up from the airport last night, and I was instructed in an email to look for a “blonde woman that is extremely tall, she will stand out.” Sure enough, in a sea of Samoans, Tori stands out. She has adjusted to the island after 7 months of working at NPSA and embraced many of the traditions here. As a native Ohioan, she has a wholesome flavor to her and is probably the most hard science/technically focused of the team.

The shoreline of Olosega Island.

After a short drive, we enter a chaotically arranged grocery store and Tori excitedly exclaims, “Zucchinis! I haven’t seen zucchinis since I’ve been here!” As beautiful as American Samoa is, it’s geographically closer to New Zealand than the mainland US. Being that far away creates challenges for trade, and particularly for produce since very little is grown in Polynesia.

We are shopping for our upcoming trip to Ofu Island in the Manua islands. Ofu is about 75 miles away from Tutuila, where the National Park Service (NPS) is based out of. We will be flying out tomorrow on a small 12-passenger plane. There are about 150 people that live on Ofu and about 200 that live on Olesega, which is connected to Ofu via a narrow, 100m long bridge. Needless to say, provisions are hard to come by on the island. Once we pack up the car, we head to park headquarters to ready our coolers for the morning.

Our destination is in Manua. Here are the beautiful islands of Ofu and Olosega.

After Tori introduces me to some of the park staff, I meet Bert Fuiava, Park Diving Officer and acting Marine Ecologist at the National Park of American Samoa (NPSA). Bert is a massive man. In the words of the acting NPSA superintendent, Daniel George, “Bert’s arm is the size of my leg!” Bert’s muscular exterior belies his fun-loving personality. Though he works extremely hard, he is the biggest prankster on the NPSA team and embodies the “no worries” island attitude.

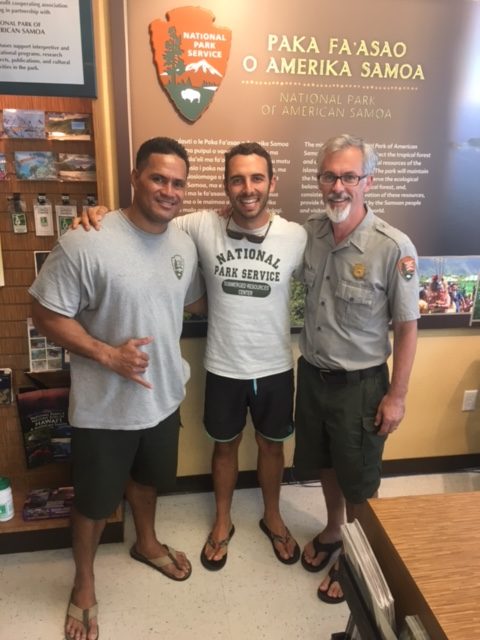

After I meet Bert, I meet Ian Moffitt. Ian and I connected virtually many years ago. Truth be told, I have applied to work at NPSA multiple times over the years. Being from Los Angeles himself, Ian and I have a mutual contact that connected me with him years back. After occasional internet chats, it is great to actually meet him in person. “Want to come help me out with some boat stuff real quick?” he asks me.

(L-R) Bert Fuiava, myself, and Daniel George at park headquarters.

Soon enough, we are at the NPSA boat yard. Ian shows me around and I get to work gathering equipment for Ofu and doing a bit of housekeeping. Unfortunately, Ian isn’t coming with us to Ofu, so this may be one of my only opportunities to talk with him. Ian’s been in American Samoa for almost 3 years- the longest of any of the pelongis (non-Samoans) on the NPSA team. He tells me about the benefits and challenges of his stay on the island and how his career has progressed at NPSA. Without Ian, NPSA would have trouble continuing their dive program. His mechanical knowledge is a precious resource, as he keeps all the park boats up and running. We also talk about our hometown of Los Angeles a bit as well. I don’t always have a hunger to be around people that grew up in the environment I did, but it is really nice every now and then. Ian is such a solid guy. He is constantly working and hyper focused, but knows how to have fun and isn’t so serious that he can’t crack a joke every now and then.

Tutuila is one of the hubs of the tuna industry in the Pacific. The scene of locals preparing nets for massive international fishing vessels is common in Pago Pago.

Tori, a few of her friends, and I are lathering up in bug spray at Tisa’s. Tisa and her husband, who oddly goes by the name of “Candyman” run Tisa’s Barefoot Bar. It’s a bar/restaurant that makes from scratch or catches nearly everything they serve- including fresh fish and piña coladas. While Tisa’s food and drink was the draw for us, I was more interested in their Marine Protected Area (MPA). Tisa and Candyman manage the MPA that lies directly in front of their business. “Their giant clams are the biggest I’ve seen on the island,” Tori tells me.

I ask Candyman how they deal with poachers. He tells me that it’s usually easy because they can see them walking on the beach or snorkeling on the surface, but lately it’s been tough. “There are no scuba shops on the island, but people are still getting scuba gear here. They go out at night for the clams and they are hard to see underwater. I’ve been kayaking out though and dropping some rocks in the water when I see lights!” Though this sort of management would never be considered acceptable in the developed world, it is working here and quite an inspiration to me.

“So apparently there’s a matai on our plane,” Tori tells us as we are loading up the van in the morning. Matai’s are high-ranking Samoan chiefs. Having a matai on your plane means that you and your luggage will not get priority and may or may not make it to your destination. Normally, this isn’t a huge deal. However, there is only one flight a week to Ofu. Even though we sent most of our heaviest equipment via boat last night, not having our gear (or even worse, crew) for the week would be devastating.

Ofu’s corals have quite the reputation and it’s easy to see why!

Once we get driving, Daniel lightens the mood. He says, “someone described these planes to me the other day as a ‘flying busses,’ which is comforting…how high do these planes go?” Bert responds, “4000 feet I think.” “Ok, good. If it was 5000, it might be a problem, but I feel totally fine hoping out of the plane at 4000 feet if it comes down to it.”

This is the essence of Daniel. Daniel has spent most of his life on the Pacific coast of the lower 48 and currently heads an Inventory and Monitoring team based out of Pinnacles National Park in California. He perfectly walks the line between being professional and having fun. As such, he is quite popular with his team. Daniel is also one of those people that is probably the smartest person in any given room that he walks into. He is an avid birder that leads his team by example with a strong work ethic and is probably the funniest person I’ve met all summer.

The plane coming down on the runway at Ofu Island.

Once we get to the airport and grab a quick breakfast, we board the plane with the matai without a hitch. After unsuccessfully looking for whales outside my window for 30 minutes, we arrive on Ofu and head to “the lodge.”

The bridge that connects Olosega and Ofu.

The lodge is a 1-minute walk from the airport (note that the airport is just an airstrip and an open structure). It’s odd to not have to find transportation to my destination from an airport, but really convenient. The lodge sits right by the coast and next door to the NPS visitor’s center on Ofu. A married island couple named Ben and Deb run the lodge. They each spent significant amounts of time stateside and can communicate and connect well with their guests.

Elsa and Jason Bordelon inspecting a prized delicacy on the island- coconut crab.

We quickly put away our food in the breezy kitchen of the lodge to a reggae soundtrack and start putting together gear for the day. While we are gathering up the equipment we need, I hear 3 year old Elsa Bordelon exclaim, “best day ever!” as she looks out on the ocean. Elsa is the really the star of the trip. She is the daughter of Jason Bordelon, Chief of Interpretation. Jason and I bond quickly as he also spent several years on the west end of Catalina Island and likes to surf. Between Elsa and work, Jason is staying pretty busy on Ofu. Elsa is a free spirit if there ever was one and makes the whole crew laugh throughout the week.

There is a small store on Olosega where residents can buy mostly canned goods. Chicken is also available in zip loc bags.

Once we are ready to go into the field, Bert, Tori, and I hop in the truck with the Ofu NPS team- Brian and Boy. Ofu is of particular interest to the scientific community because of what happens in its nearshore “pools,” where seawater gets held up at low tide and the interaction with the open ocean is limited. These pools heat up to above 90 F, which is much hotter than corals should be able to withstand. Yet, the corals in the pools are thriving. Why is this? What makes these corals different? Does this provide us hope in the face of a warming ocean?

- I believe this is a Montipora species, it is quite abundant in Manua.

- I hadn’t seen Acropora coral this healthy all summer until I arrive in Ofu.

- The same can be said for this tabling Acropora coral.

- More Acropora!

NPS is continually working with Stanford and Old Dominion University to answer these questions. This week, we are taking water quality samples (just like I did at KALA) as part of the Inventory and Monitoring process that goes on in the Pacific, as well as looking at coral reef plots that partnering universities are researching. The latter exercise involves us finding corals that the university has tagged in the warm pools, retagging them (the tags get covered in encrusting algae very quickly), and taking photos so that all involved parties can analyze how quickly the coral is growing, bleaching, or receding. The idea is to find which corals are growing well in the warm pools and why that is.

Massive, bouldery Porites corals make up the majority of the coral cover on the island.

As we are taking our water quality samples, Bert is teaching Boy and Brian how to do it so that they can help with the study when the Tutuila-based team isn’t on Ofu. After we go to several sites and finish all of the water quality samples we need to take on Ofu, we call it a day and head back to the lodge.

It’s a warm afternoon on Ofu and Tori and I are swatting mosquitos off ourselves. We are on day 3 of our Ofu mission. I’m getting the hang of searching for tagged corals. It’s been very challenging because the tags are small to begin with and are often completely fouled or missing. We are struggling with certain tags more than others and start to see a pattern of which ones are missing. This helps us determine where we need to make new sites versus where we should actually spend effort looking for tags.

Bert inspects one of our new tags, they are never this obvious when you come back to them in 6 months time.

After our second site of the day, Bert shouts out, “Sione!” Sione is my name in Samoan and has become my nickname on Ofu. “Let me see how you husk a coconut!” I told Bert that I can husk coconuts- which is true. There is a perfect husking stick at this site. The thing is, I haven’t had a perfect husking stick to husk a coconut on in 4 years. It should be easier, but because I’m out of practice and have been husking coconuts with a pocket knife all summer, I struggle a little. About 8 minutes later, I’ve husked my coconut. “I’ll show you the Samoan way!” Bert says, as he proceeds to husk a coconut in about 20 seconds and we all laugh.

Tori records data about the corals and the number of our new tag to makes sure it all makes sense for both NPS staff and collaborating universities.

As day turns into night, we are all cooking dinner. I look at the food Daniel brought, which is only rice, beans, and quinoa. I have to ask him. I turn to Daniel and say, “are you vegetarian?” I am hoping for a fellow vegetarian in American Samoa. Despite how every single person I’ve met who has been to American Samoa has told me how difficult it is to be vegetarian here, it’s actually not too hard. However Daniel is not a vegetarian, “I’m mostly vegetarian, but I’ll slam an animal every now and then if I need to.” I can’t help but crack up at that statement. Slam an animal?! That has to be one of the funniest ways he could have put it.

Coral nurseries like this are common in Ofu.

Though Daniel is hilarious, what I admire about him most is his commitment to his values. The reason he brought so little food with packaging to Ofu was because knows that what is brought to Ofu gets put into a “dump” (a hole in the ground) on Ofu and often will end up in the ocean or burned. In order to reduce his footprint on the island, he brought food that has the least amount of packaging possible. This is what a leader should be doing.

Daniel dives in to get a photo.

My scuba boot tan is pretty spectacular right now. After 5 days of surveying, the back of my legs are extremely tan and the skin under my boot line is not. Today, we are also doing some video surveys along our transect lines. The way it works in-water is Bert and I set up the transect tape at each site, then Tori swims along the tape taking video. The video is analyzed later and compared to past videos. NPS is specifically looking at coral cover and coral health from previous survey to this survey.

Healthy corals mean healthy fish!

Additionally, we are taking a cow bile mixture with us today in case we see any crown of thorns sea stars (COTS). COTS are native to Samoan waters, but they are what I like to call “coral reef lawnmowers.” They are ravenous coral eaters and don’t really have natural predators. It’s difficult for humans to remove them as well since their bodies are covered in venomous spines. As such, having multiple COTS in a small area can spell death for that entire section of reef. NPS uses cow bile to kill COTS. It is inserted into the COTS through a syringe and will disintegrate the COTS within 24 hours without harming any other marine life.

The white “scar” on the coral on the left side of this structure was caused by the COTS that ate it, cryptically hanging out under the overhang. COTS are generally much more active at night than during the day.

After our first site, we head to a site where we’ve been seeing COTS throughout the week. I take my camera in the water. Tori, Brian, Boy, and I look for COTS while Bert holds the cow bile mixture. After about an hour of work, we inject 10 COTS. American Samoa experienced a massive COTS outbreak many years ago and it has been the primary objective of NPSA to manage the outbreak until this year when it was deemed managed. All in all, they killed over 26,000 COTS.

A more conspicuous COTS. They really do live up their name, don’t they?! Crown of thorns?

This is even more impressive when considering the logistical challenges of American Samoa. There are no dive shops nor places to get boat parts in American Samoa, and shipping to and from the territory is unreliable at best. That being said, the fact that Brian and Boy can accomplish the things they accomplish is even more impressive. They are the only two NPS employees on Ofu.

Throughout the week, I’ve gotten to know Brian and Boy pretty well. Brian is a clear communicator who has infinite curiosity and an open mind about his new island home (he’s been on Ofu for about 3 months). He is supported by his wonderful bohemian wife, Rebecca- a California surfer with the most caring heart. Boy is a local. Born and raised in Manua, his local knowledge helps fill in the culture and local ecology knowledge gaps for Brian. Boy is also one of the hardest workers I’ve met this summer.

Bert injects a COTS with cow bile as Brian looks on.

After a long day of surveying and COTS management, we head back to the lodge. Jason and his family have ordered dinner tonight as a special treat and the dinner is a locally speared fish. Daniel and I start to talk about the experience of a speared fish and Daniel says, “yeah, I imagine that the fish probably tells his friends ‘hard pass’ in regard to being speared.”

Later on, Daniel and I team up again. This time, it’s to take down some of the locals in a game of billiards, and by take down I mean that our goal is solely to keep our dignity in tact after we leave the pool table. We proclaim ourselves “Team Pelongi.” As Team Pelongi gets the game started, I miss an easy shot. Daniel jokes, “oh nooo! Your whole family is embarrassed and they’re not even here!” I end up laughing so hard, it’s difficult to finish the game. I never get tired of Daniel’s humor.

Marine debris is an issue even in the remote waters of Ofu.

Today is our last day in Ofu. The mission for today is removing some marine debris that we spotted a few days ago at one of our sites. There is a huge fishing net wrapped around a dead coral head. It likely killed that coral head along with countless others. It’s hard to say if it also killed other, larger animals in the ocean, but marine debris does that more often than not.

The team works to free the net.

Once we are at the site, we find the debris and begin moving it. Boy brings a machete, which makes the process surprisingly quick. Within 2 minutes, the net is ready to be removed. My job is to document the whole thing, but by the time I’m ready to shoot, they have almost removed the net! Once the net is removed, the team drags it onto shore and into the truck.

Run Forrest, run! Boy leads the charge taking the net back up onto the beach.

After the removal and some fun snorkeling, we go over to Boy’s family’s land to harvest some young coconuts. Brian picked some would-be trash and turned it into a pole to knock coconuts off of trees. Once we have 7 or 8, Boy starts giving us a lesson. “You see? Like this,” as Boy flicks a coconut to show us how to tell if it’s good or not. Then he starts flaking off the top of the coconut with his machete. I ask him I can do my own, because I’ve always wanted to try. He agrees and I start hacking away to get the perfect drinking hole in the top. The process is really fun for a beginner but also a little more difficult than it looks. How do the locals have such pinpoint accuracy with their machetes?

I leave American Samoa tomorrow, so I need to finish editing all of my photos and get my last good byes in. My first stop is the NPSA office. After many hours of editing, I say my goodbyes to Jason and Bert. “Sione! This is for you,” Bert says giving me a NPSA shirt. I thank Bert for hosting me, all of his hospitality, and showing me the ropes on Ofu. I also tell him to come visit me in California when he and his family go to their second home on the west coast.

Later that evening, Ian and Paolo (another NPSA employee) come over to hang out with Tori and I. Ian brings up something I said after meeting him last week, “We’d been talking for no longer than 5 minutes, and then I’m walking out the door to help someone and I hear you say ‘thanks Ian, you’re so cool and thoughtful!’” Paolo lets out a laugh, “cool and thoughtful! HA! That is classic!” Ian puts things into context, “I was kind of stressed and didn’t even notice when you said it. Then I was like, wait, did he just say that?! Was that a joke?! Ha ha ha.” For the rest of the night, “cool and thoughtful” becomes our phrase of choice. “I hope that ‘cool and thoughtful’ becomes my legacy at NPSA,” I laugh.

Boy reaches to play with an octopus on Ofu.

I had a blast with Paolo and Ian. It’s really fun to be around two California guys so far from home. Unfortunately, I say my goodbyes to them and Tori when Daniel picks me up for my flight. Daniel is my last goodbye. I tell him that I am going to contact him when I get up to Pinnacles one of these days and that I think he makes an excellent Superintendent.

American Samoa is one of the most remote and unique places in the National Park Service. It was such a privilege to be able to go to NPSA, and particularly Ofu. It was the perfect end to my summer tour- a beautiful landscape and equally beautiful seascapes with the best crew I could ever ask for. I was also happy with my own effort and work at NPSA, which is a great feeling to have. I would say that I feel like I finished on a very high note, but truth be told, I’m not finished. In 36 hours, I’ll be in Washington D.C…