This final short week in Biscayne National Park was almost definitely the one week of my internship that I was most nervous for. By a wild stroke of luck, I had been handed an incredible opportunity: a chance to take photos for a magazine, something that many photographers dream of. Mary Frances Emmons, editor-in-chief at SCUBA Diving Magazine and good friend of Dave and Brett, had reached out to Brett asking if he’d be able to photograph a program happening at Biscayne National Park this summer. Brett was unavailable, as he had SeaArrays to drive and shipwrecks to model, but as luck would have it he would have an intern in the area right around the same time – me.

The job was to photograph this year’s maritime archaeology segment of the Youth Diving with a Purpose program, an initiative to get underprivileged youth into subtidal work through archaeological and biological experience. I’d be working with a journalist and a few members of the Parks Service to document and assist this program during its time at Biscayne. This was obviously something that I was very excited for, the chance to not only have published photos in a major magazine but to shoot on assignment as well, but also a daunting task.

This was my first real underwater photographic assignment and a big one too – the folks at SCUBA Diving had taken a bit of a gamble on me, trusting the good reviews from Brett and Dave and hiring someone with no real magazine experience as the only one to provide photos for their article. I was honored that everyone had so much faith in my shooting ability and determined to make them all proud. However, I knew this assignment would touch on some of my weaknesses as a photographer. Despite spending most of the past couple years taking photos, my photographic experience was limited in two major aspects of this assignment: taking topside photos and underwater shots of people. Most of my experience comes from underwater wildlife photography, so while I was very comfortable using a camera I was a little hesitant as to how to approach this. Thankfully, the past couple weeks of this internship had been an excellent warm-up with the large number of images I produced for my blogs.

The program that I was assigned to document, Youth Diving with a Purpose (YDWP), is one that the SRC has been collaborating with for a while. YDWP is an offshoot of the successful Diving with a Purpose, a nonprofit designed to preserve and protect submerged cultural resources while also providing archaeological education and training. These programs have a special focus on shipwrecks of the African slave trade and uncovering more detail about the maritime history and cultures associated with this. A specific maritime target of the group since its founding is the wreck of the Guerrero, a high-profile slave ship that is believed to have sank somewhere off the Florida Keys. This particular vessel has yet to be located, so in the meantime the group is focusing on assisting the Parks Service with mapping the many wrecks located within the boundaries of Biscayne National Park.

This year, students from across the U.S., U.S. Virgin Islands, and Costa Rica travelled to South Florida with a team of instructors to tackle the mapping of a wreck in Biscayne called BISC-60, or Captain Ed’s wreck (named after the Captain who discovered it). This site is the remains of a mid-1800s vessel, lying in 22 feet of water just above the southern border of the Park. These students would spend a day in the classroom learning the basics of underwater mapping and maritime archaeology along with some history about the park, before venturing out into the field to put those newly discovered skills to work.

This week started off with a long day of lectures and land-based exercises. I travelled to the Dante Fascell Visitor Center at Biscayne National Park with the team of NPS personnel who would be assisting the YDWP team this week: Dave Conlin of the SRC, David Gadsby (an archaeologist from the Washington branch of the NPS), Josh Marano (maritime archaeologist with south Florida parks), and Sydney Pickens (a recent YDWP graduate and budding marine archaeologist). While my main job would be to photograph the program, the rest of the Parks Service team would be working to facilitate the program from the Parks side of things: setting up the classroom and the wreck site, making sure the program has everything they needed, and of course lending their valuable expertise.

- Dave Conlin teaches the group about maritime archaeology

- YDWP’s Ernie Franklin lectures on the history of the program

- Florida Public Archaeology Network’s Mallory Fenn teaches scientific illustration

While the students got an assortment of lectures, ranging from everything from the history of the DWP program to scientific illustration, I worked to document the process. Taking classroom photos of lectures and illustration practice wasn’t the most exciting thing I’ve done during this internship but was still something that I took seriously. Thankfully, I was also able to pick up a little of the info that the various lecturers had to say, learning a little bit about the Park, the history of YDWP, and about maritime archaeology. After taking a couple hundred shots of the students hard at work absorbing lectures and practicing their sketching skills, we moved onto a welcome outside break to practice the mapping process itself.

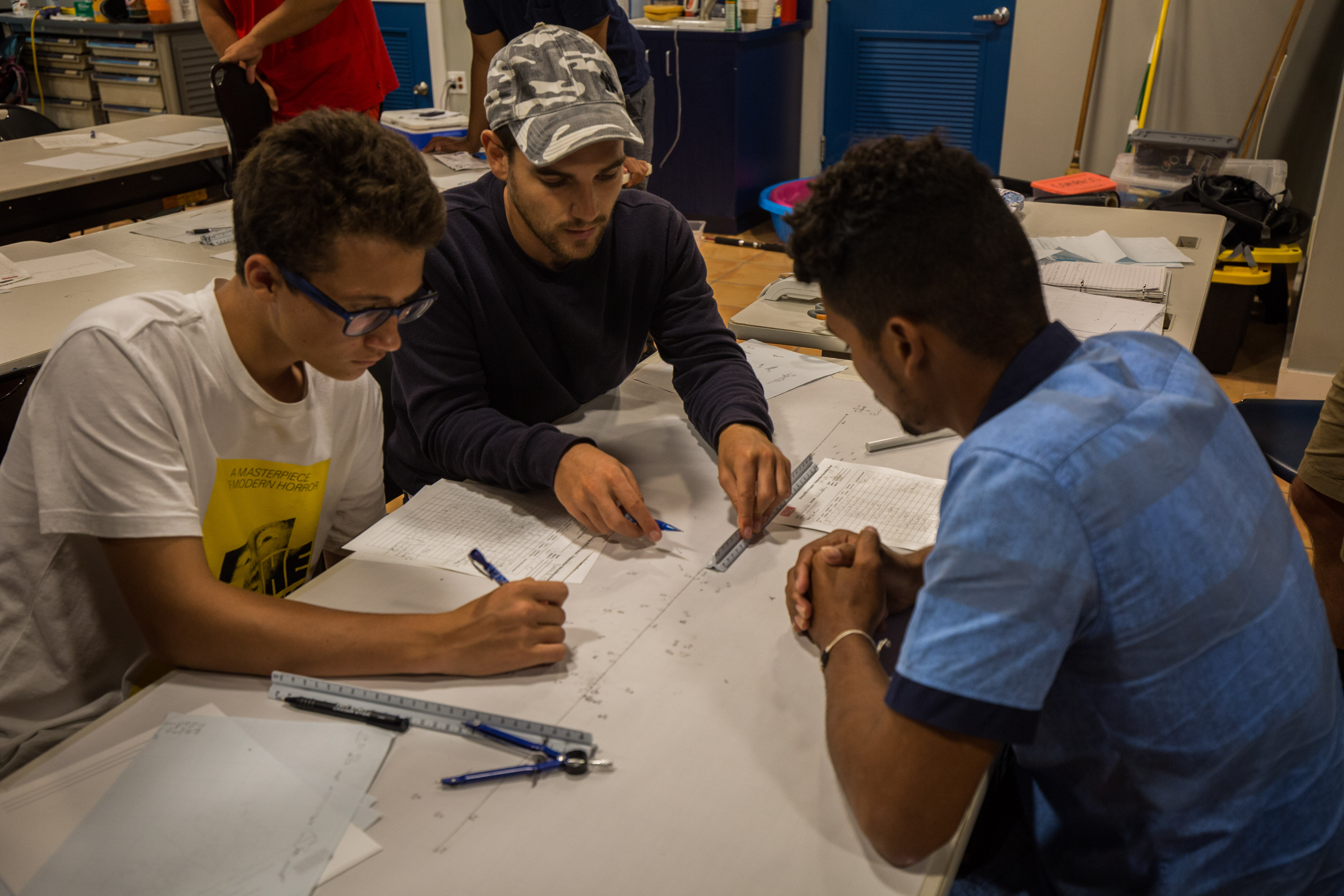

As minutes underwater is much more precious than those on land, the YDWP instructors took their time in ensuring that the students were very clear on the mapping procedure before they even stepped foot on a boat. In the muggy Florida heat outside the visitor center the students gathered to watch the instructors demonstrate mapping on a mock shipwreck – an assortment of objects laid on the grassy ground. This was a fun experience for me as, like these students, I had no real experience with mapping shipwrecks. I’d been able to observe the Submerged Resources team modeling quite a few with next-generation technology but had never really learned much about the old-fashioned way of doing it – with pencil and paper. Using measuring tapes and lots of patience, the instructors thoroughly explained the basics to the mapping to the students – including trilateration, how to take careful and accurate measurements, and the importance of not disturbing the baseline. The baseline, a transect tape that is reeled out through the middle of the site, is what all measurements are made in reference to. If it gets uprooted or moved before the in-water mapping is finished, all progress could be lost.

- Instructors Justine and Kramer demonstrate proper mapping technique

- Instructor Andrew helps his team with their mapping practice

- Instructor Justine works with her team in taking measurements

Early the next day, I met up with the NPS team to head out to our site. We were going to arrive a little earlier than the YDWP folks, who were departing with a dive charter out of Key Largo, to set up the marker buoys and the baseline. Arriving at the wreck site, the water was wildly calm – not a ripple to be seen. Josh and David geared up and hopped in to set up the lines while Sydney and I swam around to get a quick look at the site before the group arrived. The serene calm on the surface of the water extended to the dive site, as water motion was negligible. Perfect conditions for the first day.

Soon after we’d gotten in, the YDWP team arrived and it was time to get to work. I wanted to have the maximum amount of time possible to photograph them, so I went down as soon as the first people started dropping in. Now, before starting the dive I was a bit hesitant as to how my shots would all turn out, but I had clear ideas of what type of photos to produce and was confident in my ability to procure them. I’d had a lot of practice photographing people doing somewhat similar work in earlier parks so I figured this wouldn’t be too different – but boy was I wrong. I hadn’t accounted for the sheer amount of people on such a compact site – there were four different teams of 4 students, each team with an instructor leading them. This wreck wasn’t huge either, at one side it compacted into what was roughly a 10X4m area (and this is with 10 divers working in it). To make things worse, divers were now fighting a slight current which had just picked up, forcing everyone to maintain a slow kick into it.

That’s a lot of divers – in some parts of the site, divers had to work in very close quarters to get their measurements done

These crowds meant one important thing to me, something that I hadn’t foreseen. With so many people on the site, it was difficult for me to produce clean shots without distracting background action. It seemed like every time I spotted a team doing some work that would display nicely and moved into position, someone else would drift into the background of my composition or a rouge fin would appear from outside the frame. Wanting to create distinct images without parts of people cutting in or out of frame, I ended my first dive disappointed. I felt as though I had largely failed on my mission and had to re-plan my approach to get less busy images. Thankfully the group was doing at least 4 dives on the wreck, so I had a couple more chances.

Some images (like this one) turned out nicely but still had a few more people in the background than I’d have liked

The next dive went slightly better, although there was also some added difficulty. I had received a request by the YDWP instructors to get portraits of each student underwater, so added this concept to the back of my mind while trying to get clean magazine shots. Trying to isolate single students out of the masses was difficult in itself, but I also ran into another problem that I didn’t really think I’d ever have: no one would look at the camera. Typically, when shooting people underwater I don’t really want that, I’d prefer to have the people as an accessory in the shot for scale or added impact and to have them look towards the subject – but for portraits it’s a different game. I did admire the student’s steadfast dedication to the task – despite my shoving a camera in their face and praying that they’d look at it (even for just a second), no one caved. I ended the first day of diving feeling unsuccessful – I hadn’t managed to produce many clean working shots and had only gotten nice portraits of one or two of the students. I knew I had to approach things differently for our upcoming dives.

Students were so absorbed in their mapping that they paid no attention to the photographer snapping away photos right in front of them

Overnight, I had pondered plans for ways to isolate my subjects and get clean shots. I had thought up ingenious ways to briefly distract the students to take their portraits, and clever methods of capturing backgrounds free of rogue divers. As it turned out, I really didn’t need any of these. This day I was to ride out of Key Largo with the YDWP team and took that opportunity to ask a couple of the instructors if they’d mind assisting me with the portraits a bit and running their students by me at the start of their dive. I’d planned to be waiting right beneath the boat and the teams could drop down, stop by my marine portrait station, and then be on their way. As always, this proved to be much simpler in theory (I ran into issues with teams jumping in at the same time, forgetting to stop by, or just getting in each other’s photos) but was much easier than yesterday’s approach. With some light hounding on some of the instructors, I managed to get everyone to bring their students past me for picture.

As for the magazine shots, things just seemed to work out in my favor that day. Students weren’t as tightly packed together on the wreck, people weren’t swimming around as frantically, and everything seemed more relaxed and calm. While still requiring careful compositions and an ever-vigilant eye to watch for roving divers, I had a much easier time getting good photos this day.

For such a seemingly small event, this year’s YDWP was getting a bunch of attention. There was obviously the article for SCUBA Diving magazine, which myself and a journalist were working on, but there were a couple other media outlets: AARP sent out a team to do an article on Ken Stewart, the founder of YDWP, and Washington Post was there doing video piece as well. On top of that, the program attracted some high-ranking Park officials. Joe Lewellyn, Acting Superintendent of Biscayne, came out for a day on the water, as did Pedro Ramos, Superintendent of Everglades and Dry Tortugas. Florida Public Archaeology Network’s Rachel Kangas rejoined us for a dive too- everyone wanted to see this program in action. Pedro Ramos joined everyone on the YDWP boat and spoke many kind words encouraging the students to continue this work and stressing the importance of them striving to uncover this history. It was nice to see all the Park support for this impactful program, an excellent use of our public lands in an educational and outreach-oriented program.

- Pedro Ramos and Dave Conlin on the wreck

- Pedro Ramos speaks to the YDWP Team

After the first two days of diving, it was time for our last day in the classroom – the mapping day. This was when the students would put their field illustrations and measurements to work, taking all of the info that they had gathered while underwater and transcribing them on land. First, they’d map out their portion to scale on a little personal map, and then once they’d finished add that section onto master map with the entire wreck on it. This was very cool for me to see, all the hard work that I’d observed happening underwater turning into a tangible product, and something that I’m sure was very satisfying for the students as well.

The mapping day was much like our first classroom day, with lots of hard work indoors sketching away, but this time everyone knew what they were doing. The students worked a hard, long day turning their field sketches into a polished result. Unfortunately, their work wasn’t done yet. As these things sometimes go, they needed just a few more measurements to get the map finished. Thankfully, a day was left open just for this possibility. Friday, our last day in the program, was left open for any potential re-measurements so we went back out.

Only needing a few measurements, Friday wasn’t too hard of a working day. We still did two dives, but they were both very relaxed. Most everyone was taking measurements on the first dive, collecting the last little bits of data that they needed for the map. After a nice long surface interval, where the YDWP team experimented with an ROV to compare their map with one generated from ROV-collected photos (a new approach that the group is testing out), we went back in for one final time. With almost all the necessary data collected at this point, this was more of a clean-up and fun dive. Seeing everyone swim around and just enjoy absorbing all the maritime history was nice, and a good way to polish off the trip. At this point I had gotten pretty much all the shots I’d wanted for my magazine assignment, so I worked with the journalist from Washington Post to capture some video clips for her story – another fun venture into the world of media for me.

After Friday’s final dive, the team finished up the week with a victory barbeque. Gathering up to celebrate the hard work and accomplishments with good food and drinks was a lovely way to cap off the project. Just before this, I was able to polish up all the portraits I’d shot and deliver them to the YDWP instructors, which was also a nice experience. Everyone was very kind in thanking me for joining them. While I joined the group for a photographic assignment, by the end of the week I felt like I was more than just their photographer. The instructors and students were very welcoming to me, despite not knowing me, and were open and accepting to me joining their program and photographing their every moment. As someone who hasn’t done many assignments like this, I was a little hesitant at first to get so up close and personal with the team – at first, I felt like an outside viewer, invading personal space for the shots. Working with this group that feeling quickly melted away and I felt at ease and appreciated – I couldn’t have asked for a better program to work with, and I was sad to see it end.

With this program wrapping up, my time in South Florida was coming to an end. Before heading out, I made sure to make time for what is becoming an Our World Underwater intern tradition – an annual meet-up between the NPS intern and the REEF during their times in South Florida. Ben Farmer, this year’s REEF intern, was kind enough to invite me to join him and some of his fellow REEF coworkers to dive at West Palm Beach’s blue heron bridge, a popular dive spot a bit north of Miami. I was able to join him two weekends in a row for spectacular dives full of interesting marine life, where we saw cool creatures like frogfish, flying gurnards, and pike blennies. I had a great time meeting up with and diving with Ben, an excellent diver, who is going on to an exciting year of working in the Turks and Caicos after his internship. It’s a pleasure seeing what exciting futures other members of the Our World family are going on to pursue.

- Flying gunard from Blue Heron Bridge

- A frogfish from our BHB Dive

- Pike Blenny from BHB

After Biscayne I left South Florida, checked out of my motel home, and headed to the airport. From there, I returned to the Caribbean for the second part of my Virgin Islands adventure: the next round of the National Coral Reef Monitoring Program, this time on St. John.