On July 19th I began the second half of my journey as the 2023 American Academy of Underwater Science (AAUS) Mitchell Scientific Diving Research Intern for the Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society (OWUSS). After departing the Florida Keys I headed back home to switch out my gear and prepare for field work in Central America.

I began by flying from Boston to Miami—I did not expect to be back in Florida so soon. After around three hours of delays due to lighting strikes, I was finally able to board the plane. Once the plane was fully boarded, we were all informed by the pilot that “the plane needs a new lifeboat, and we would not be able to take off until they found one” … what happened to the first lifeboat still remains a mystery.

Finally, I made it to Panama City, Panama where I met up with my team at the hotel.

The next morning, we headed out to a smaller airport near by to catch our passenger plane to the town of Bocas Del Toro. This flight lasted less than an hour, but had some beautiful views of the Panamanian countryside.

Upon departing the plane, we were greeted by a kind man who sang to us as we waited for our bags—I later found out that he has been there since Bobbie started working in Bocas Del Toro back in 2019!

About half of our luggage was coolers that would hold the water samples we collect in the field on our return to the states—apparently customs and airport security were not fans the many large coolers we were taking into a foreign country, but it all worked out. We then loaded all of our suitcases into a taxicab truck—which I would come to learn is the only style of taxi in Bocas Del Toro.

We spent the next five weeks living at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) research station just outside of town.

The station houses many different research teams and even some classes. There were teams researching corals, frogs, and even bats! Living at the station was an incredible experience—even if we were woken up by the resident howler monkeys at 4am.

The station also housed a ton of local wildlife!

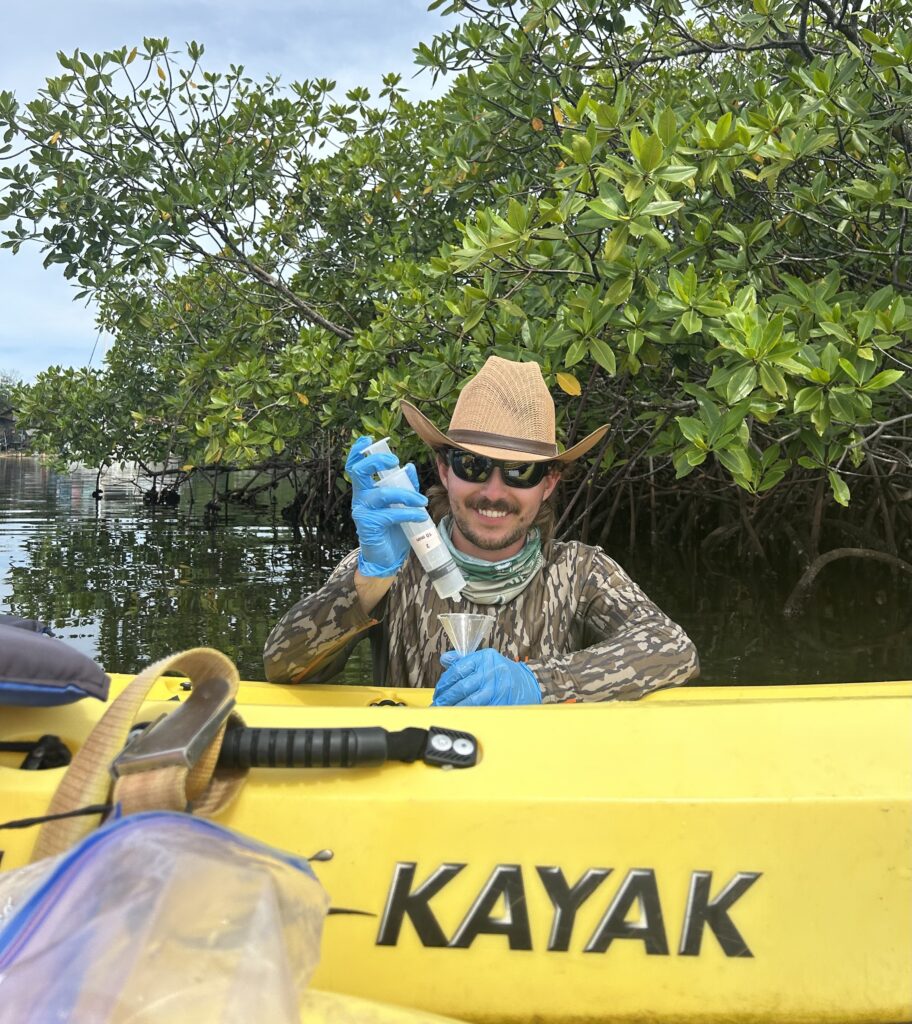

The station had a supply of boats that would shuttle us to our coral reef sites, but we did not always need them. All the coral reefs we worked at while in Bocas were very shallow, and quite close to the research station. We often used kayaks or simply swam over to the sites to conduct our field work for the day.

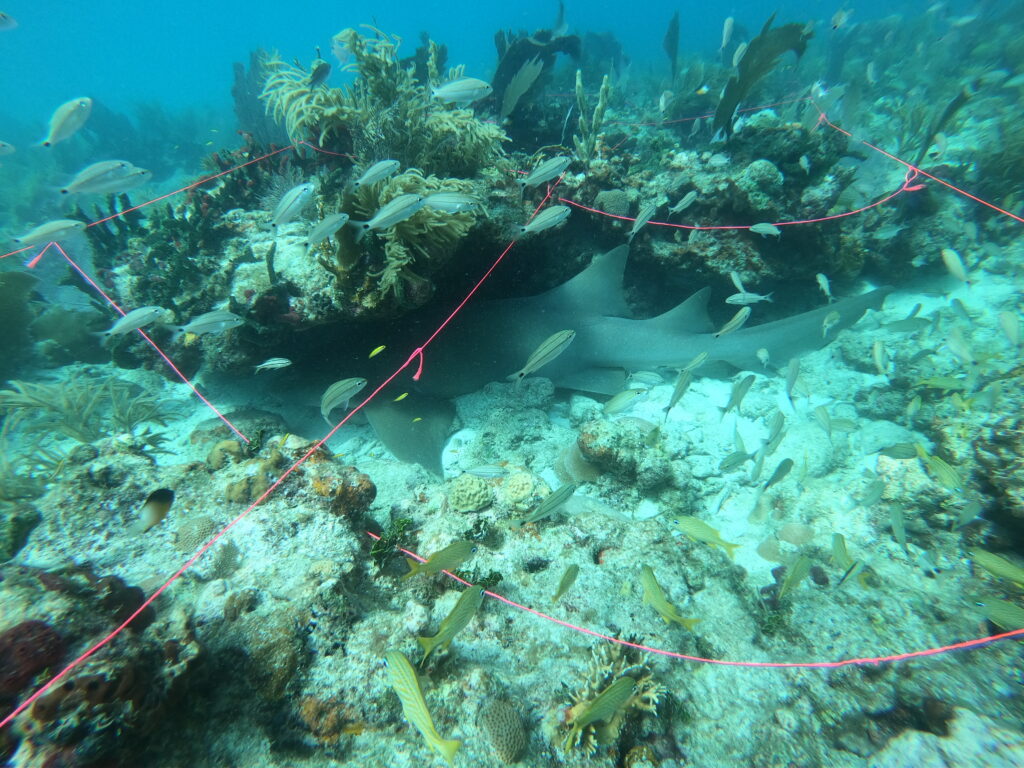

Most days were started by a visit to one of our sites to either conduct a feeding trial (find out more about this in my first blog!), or surveys of the sponge community.

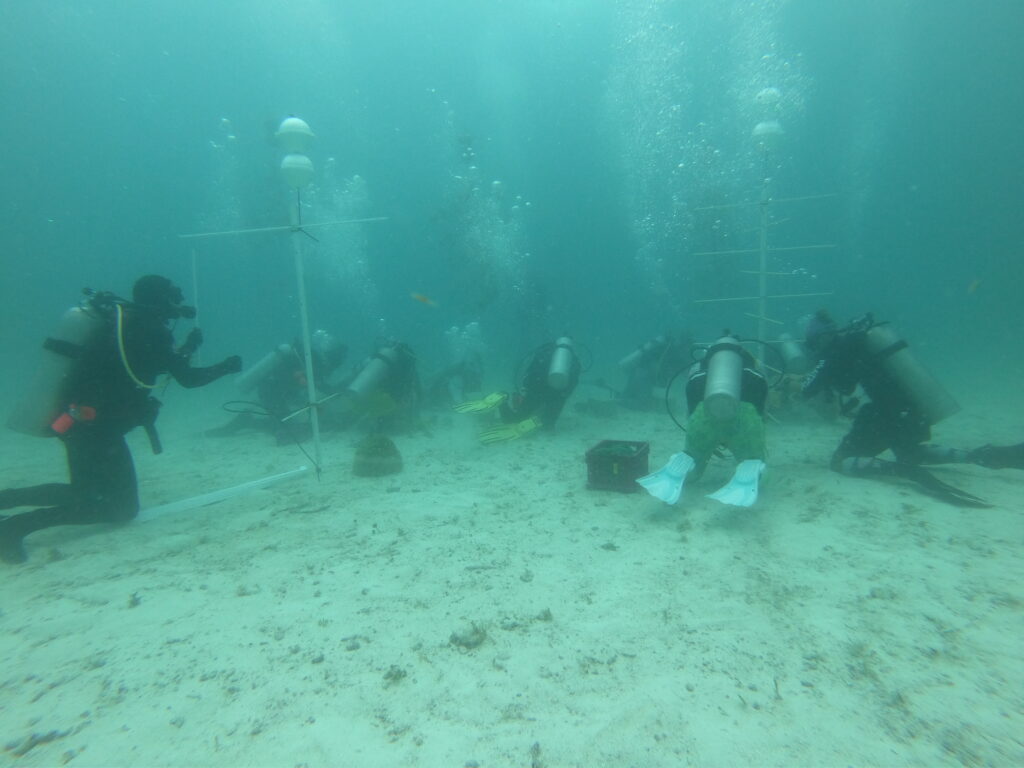

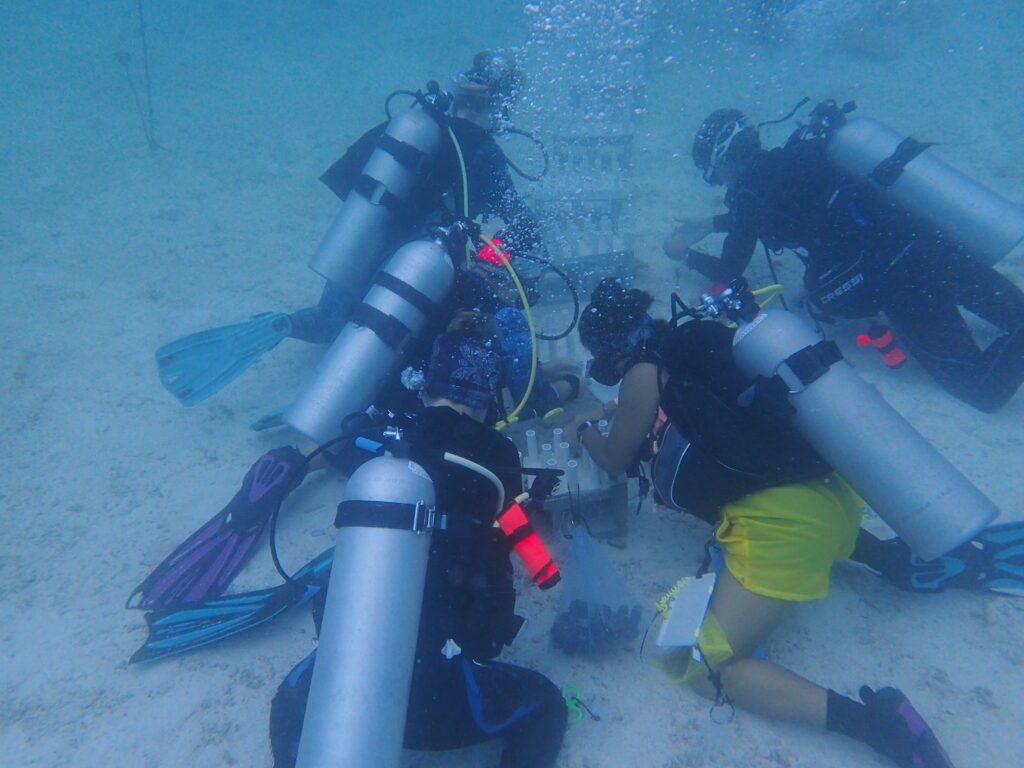

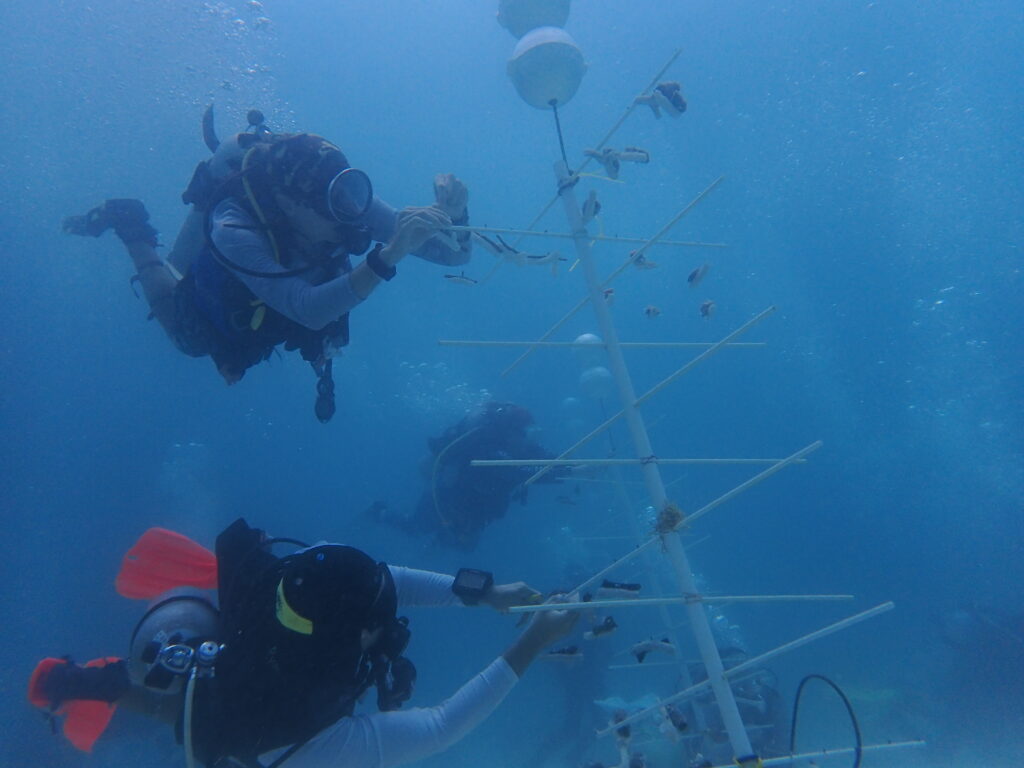

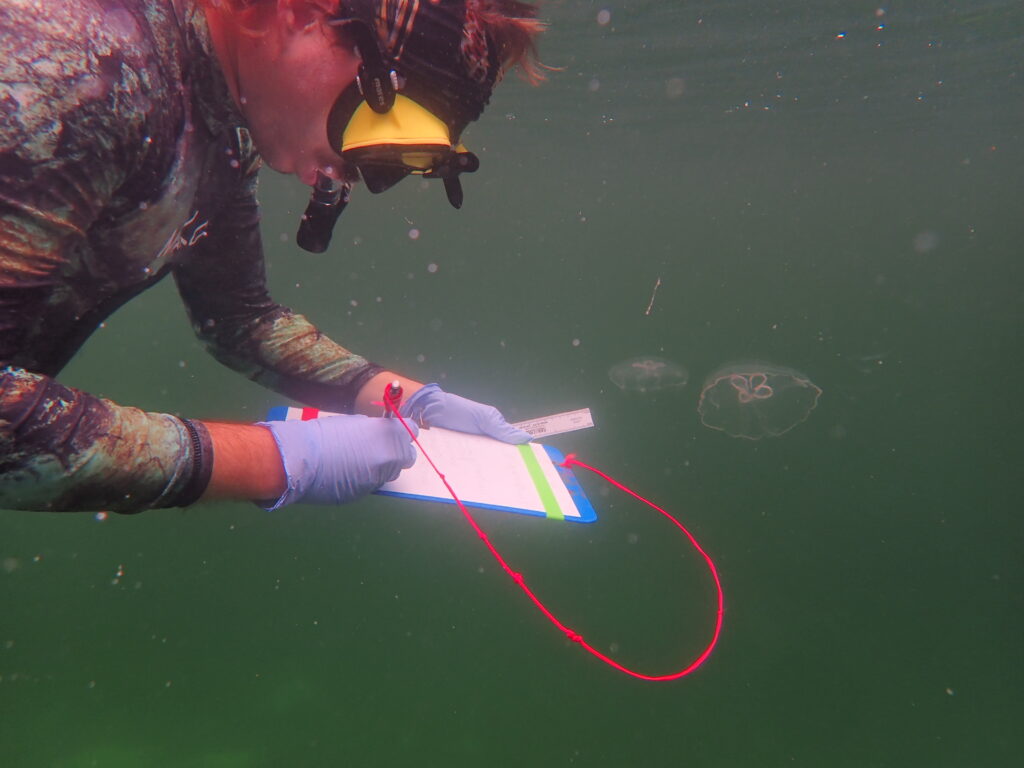

A large focus while we were in Panama was these surveys. We assembled a surveyors grid at each of our sites for ease of analysis. The method is adapted from land surveying techniques. First, we measured the volume of three specific species within the grid which were the same species we used in our sponge feeding trials.

Once we measured the three species, we did a general percent coverage survey. The purpose of this survey was to quantify what organisms make up the reef community at each of our sites.

Did you know that some sponges and anemones can be affected by bleaching events? We also conducted surveys of incidences of bleached or partially bleached sponges and anemones at our sites following a major heat stress event. I had been warned the water would be colder in Panama than in the Florida Keys but we knew something was wrong when the bay behind the research station felt like hot bathwater and not a cool dip in the sea!

There was no shortage of lab work either… especially since the lab was the only place in the station with air conditioning. Lab activities ranged from measuring weight and displacement volume for sponge samples to operating the spectrophotometer for analysis of chlorophyll concentrations within the sponge tissue.

It is surreal that I have reached the end of my internship. The summer flew by so fast—but I guess that can happen when you are underwater for 4+ hours a day. I would like to thank the AAUS and OWUSS for this incredible internship experience and a huge thanks to my host Bobbie Renfro and Florida State University. I also want to thank the entire staff of the Keys Marine Lab and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Bocas Del Toro for hosting us throughout this summer. I look forward to presenting my adventure through the 2023 AAUS Mitchell Scientific Diving Research Internship at the 2024 annual meeting.