I spent the last 10 days living aboard the M.V. Fort Jefferson, the Park Service’s supply boat to Dry Tortugas National Park, with a turtle research group from the United States Geological Survey (USGS). They come out to the Tortugas several times a year in the summer months to monitor and tag sea turtles in the area. They are seeking nesting females and adults and juveniles of both sexes. To find them, the team walks nesting beaches at night to locate females hauling up to lay their eggs, and searches shallow foraging grounds for juveniles and adults.

Our hosts aboard the M.V. Fort Jefferson were Captains Blue and Janie Douglass, and John Spade. Janie made sure that we all stayed well fed and had plenty of delicious leftovers for our nightly 4am fridge raids! The turtle team consisted of 9 researchers, students, and volunteers, all associated with USGS or University of Florida.

The project lead, Dr. Kristen Hart, is a research ecologist with USGS who has been studying sea turtles in the Tortugas for 4 years. She has been able to track individual turtles for more then 800 days with satellite tags to see where they go during different seasons. Sea turtles are highly migratory, and may traverse thousands of miles per year. Satellite tags are the best way of learning where they go and when, so that effective management strategies can be implemented and critical habitat protected for these endangered marine reptiles. Kristen has been able to determine that the turtles tagged in the Dry Tortugas travel as far as 800 km from the small island group into the Gulf of Mexico, the Bahamas, or to Cuba. In addition, Kristen deploys acoustic tags whose signals are picked up by receivers scattered throughout the park to learn more about local movements and habitat use on a finer scale.

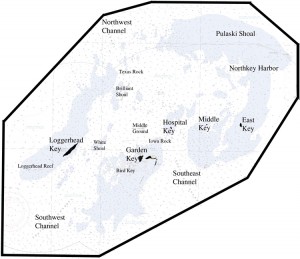

Our ten-day cruise was filled with long nights patrolling for turtles on the nesting beaches, and afternoons on the water trying to catch foraging turtles. While walking the beach at night might not sound difficult, doing it from sunset until 4 am definitely wears you out after a few days! Each night, we would set up our gear and a big circle of beanbags on the beaches of Loggerhead and/or East Keys, and take turns patrolling the shoreline every half hour. I loved walking the beaches at night; the moon has been bright and the skies have been mostly clear, with lightning flashing on the distant horizon (except for two nights when we had to cut things short due to lighting storms that came too close). In between walks, we would talk, read, do crossword puzzles, play cards, or nap. I found that mastering the art of beanbag chair napping was critical to a good night on the beach!

When a turtle was seen, we would wait for her to complete the nesting process before approaching her, to make sure that she wasn’t interrupted before having the chance to successfully nest. Often, turtles will crawl up on the beach and dig a few pits without nesting, and then head back to the sea. On their way back to the water, the team would corral the turtle to keep her in one place while they collected biometric data and attached tags. They collected standard body measurements, a blood sample, tissue biopsies, and inserted PIT tags (stands for Passive Integrated Transponder, a small scannable device-like what you put in a dog or cat in case they get lost) and attached flipper tags. Then the team attached either satellite or acoustic tags, waited for the adhesive to dry, and released the turtle to continue its journey back to the sea.

Two nights we found Loggerhead hatchlings crawling to the sea while doing patrols. I can’t describe the feeling of surprise when I saw a tiny hatchling scampering into the surf directly in front of me while patrolling the beach for 300+ lb nesting females. To imagine these minute creatures, just hatched out of a golf-ball sized egg, growing up over the next few decades to become the huge turtles that crawl onto the beaches to lay their eggs is truly awe-inspiring. Not only do these hatchlings face natural threats, from nest inundation to predators, they now are confronted with a barrage of man-made challenges that dramatically reduce their chances of surviving to adulthood. Lights on nesting beaches, rats, cats, and other non-native predators that consume eggs and hatchlings, beach erosion, the veritable obstacle course of fishing gears strewn throughout the world’s oceans, poachers, boat strikes, disease, spilled oil, climate change, plastic pollution—any one of these things can spell disaster for a sea turtle. With Loggerhead nests declining more than 40% on index beaches in Florida from 1998-2006 (for more information check out Decreasing Annual Nest Counts in Globally Important Loggerhead Sea Turtle Populations by Witherington et al. 2009), clearly Florida’s turtles are not able to hold up to such a treacherous environment. That is why work like Kristen’s is so important—the genetic and immunological information found in the blood, biological indicators from isotope analysis of the tissue samples, growth rates and body condition information from the biometric measurements, and spatial data from the PIT, flipper, acoustic and satellite tags enables natural resource managers to make the most informed management decisions possible with respect to managing sea turtle populations.

As only nesting females come ashore, turtles are also captured using the rodeo technique to get a more representative sampling of the population, including males and females who aren’t nesting this year. Rodeo catching of turtles is quite a thing to watch. We took the Carretta, a 26 foot boat that Kristen had built specifically for her research, out to shallow foraging areas where there are tons of turtles that are easily visible in the clear water. We would get a turtle in our sites and approach it from the proper angle so that the jumpers could leap from the boat onto the turtle and grab onto it as it surfaced. The boat has a tall tower with a console where the captain had the best vantage point for finding turtles and avoiding submerged hazards like shallow coral heads, and a specially built leaning post on the bow that the rodeo jumpers could hang onto. In addition, the boat has a 48 inch wide door in the side to haul in the hugest of turtles. Once the jumpers caught a turtle, the boat would swing up beside them to pull the turtle in through the door and start working it up. The team collected all the same data as they did for the nesters and applied tags. We caught some absolutely enormous turtles, including the biggest male rodeo capture in the history of the project.

To catch juveniles the team took the Livingston, a small skiff, into the shallow waters around the fort and dip-netted the youngsters to collect measurements, blood, and biopsies and attach flipper, and sometimes acoustic, tags. The majority of the juveniles captured on this trip were recaptures—they had been caught and marked in prior years. This is excellent because Kristen can track their growth rates over time and determine the site fidelity and survival rate for this population.

This is a group of extraordinarily dedicated researchers. We would walk the beaches every night starting at sundown, and wouldn’t return to our mother ship until at least 4 am. After scarfing down leftovers and all eight of us waiting for our turn to shower, it was easily 5 am before most of us got to bed. The next day we would be up by noon at the latest for breakfast/lunch, and then out to the field for rodeo or dip netting of juveniles. Then we would all sit down for one of Janie’s excellent dinners, followed by dessert every night (you need all those calories, at least that’s what we would tell ourselves!) before heading back out for more beach walks. The team worked great together, and there was never a lack of laughs or interesting conversations. When they got a turtle, the team operated like a well-oiled machine; everyone knew what had to be done and what their role was.

I was also able to get some diving in during our time on the M.V. Fort Jefferson. Kristen’s acoustic receivers had to be retrieved to download the data and replace the batteries, so John Spade and I reinstalled them in their custom built augured ports. I was the a backup diver while Blue and John did maintenance work on some of the mooring buoys in the park, and then Kayla and I got to jump in to search for Lionfish and take photos. These were my first boat-based dives in the park, and being out in the blue water was awesome. I have spent the last few years in the highly productive, and often green, northern Gulf of California, which is incomparable to the clear, warm water of Florida. The sites we dove were rocky pinnacles rising out of the sandy bottom, and were covered in hard and soft corals, sponges, and sea fans. I saw some big groupers, hogfish, and jacks, although I somehow have yet to see a Goliath Grouper! I have been pretty diligent about wearing my 3 mm wetsuit every time I get in the water to avoid sunburn and to minimize the risk of jellyfish stings, but I have actually been too warm! That is a first for me.

IMPRORTANT NOTES:

-All photos of turtles taken at night were captured using ambient moonlight and/or low-power red lights to minimize disturbance to the turtles. NO flash was used at night on nesting beaches.

-All marine turtle images taken in Florida were obtained with the approval of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC MTP #11-176) under conditions not harmful to this or other turtles.