Kristen Ewen, biologist and natural resources program manager on Saint Croix, picks me up from the seaplane terminal. It’s afternoon on a Tuesday so we’re going straight to Sion Farm and park housing so I can get settled in. I will start work with the NPS divers tomorrow. I get a glimpse of the colonial Danish neo-classical architecture of Christiansted, pastel-hued buildings, thick walls to keep them cooler, and arcaded covered sidewalks. The NPS office is in the historic Danish West India and Guinea Company Warehouse. Christiansted was the capital of the Danish West Indies and Saint Croix was booming in the late 1700s because of sugar cane and slave labor. On the drive to Sion Farm, Kristen tells me about some of the work that is going on in the natural resources department. They just finished up a long week of mangrove restoration. The season has begun for the Buck Island sea turtle nesting program and I may get the chance to join one night for a survey. I will mainly be working with the divers doing coral disease treatment around Buck Island, and at the end of the week we will join The Nature Conservancy divers to help with their coral restoration in the park. How cool!

On Wednesday I meet Rachel Brennan and Rico Diaz, the biological technicians, and Katie Owens and Nicole Rotelle, the two University of Miami interns. I will be working with these four divers for the next week and a half, treating corals at Buck Island Reef National Monument for Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD), a lethal affliction that affects over 20 coral species. Caribbean corals are afflicted by a variety of different coral diseases, including white plague, white band, and black band to name a few. SCTLD is of particular concern because while the other diseases can be virulent, they are not nearly as lethal, have as wide of a range, or have as rapid a transmission rate. A coral colony with SCTLD can develop multiple lesions that rapidly spread across their tissues at a rate of more than one inch/day, leaving behind a stark white coral skeleton. Corals die over the course of weeks to months. The mortality rate is 99% for some coral species it infects. SCTLD first appeared in Florida in 2014. Since then, it has spread throughout the Caribbean and appeared at Buck Island Reef National Monument in 2021. Many aspects of the disease are still unknown. There has been an upwards of 60% decline in coral cover on some reefs due to SCTLD.

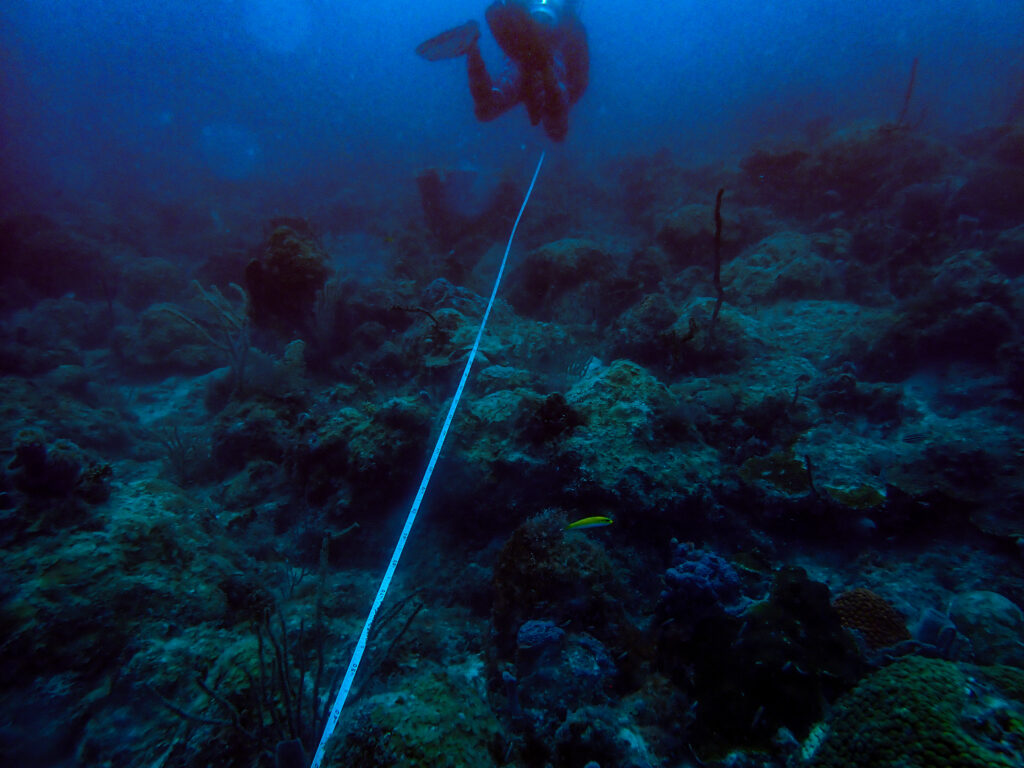

The NPS divers are working tirelessly to halt the progress of SCTLD and minimize its impact in the park. Their primary focus is preventing diseased coral colonies from dying by applying an antibiotic paste. This treatment has proved to halt the progression of the disease and boasts up to a 75% effectiveness rate on some coral species. So far, the NPS divers have treated 6, 818 corals!

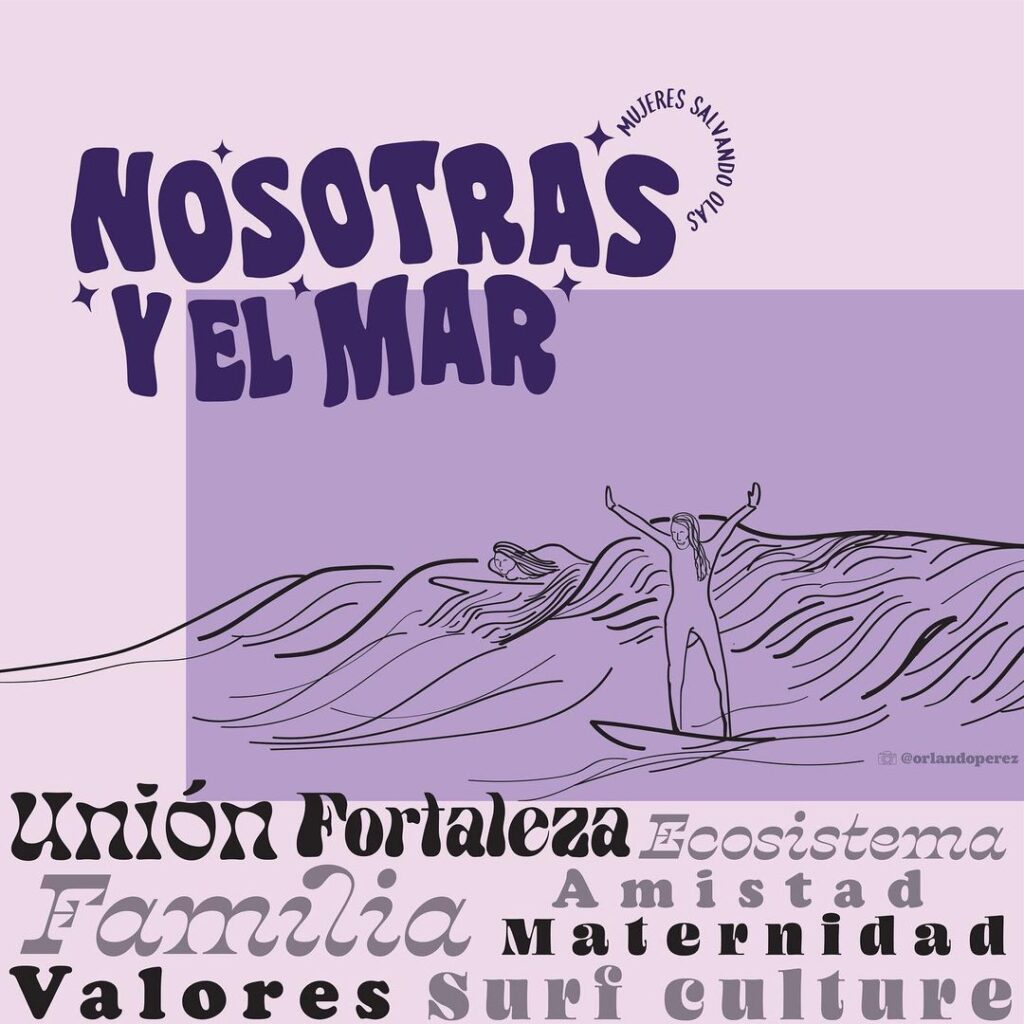

I could write quite a lot about why the loss of corals is significant. However, I’ll just keep it short and sweet. Everything is connected. If coral reefs die, humans die. We are not separate from our environment. We rely on the ecological services provided by ecosystems like coral reefs. I understand how it’s hard for people to understand the ecological crisis going on underwater. It is out of sight and out of mind for most people. There is no smoke in the air, it doesn’t appear to be affecting your day-to-day. That’s why it’s important to share the science and educate. I wrote last week that the water temperature in the Keys was over 90 degrees. Well, this week it is over 100 degrees, many reefs are experiencing mass bleaching and it isn’t even the hottest part of the season.

It may seem like an insurmountable problem and our positive actions seem so minuscule in the grand scheme of things, but I do wholly believe that everyone’s tiny individual efforts can and will add up to change our future. So let’s start by saving the corals we can save.

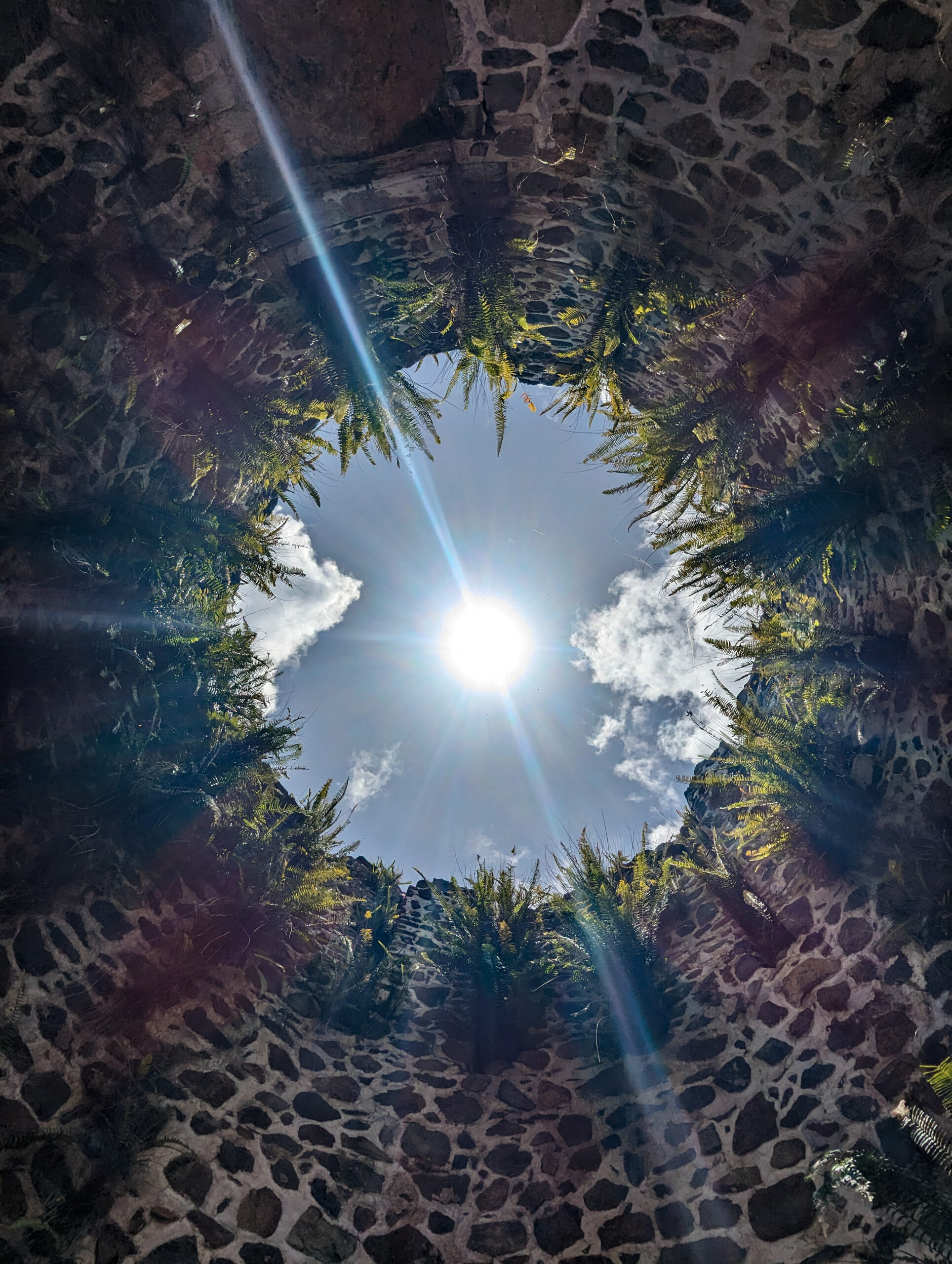

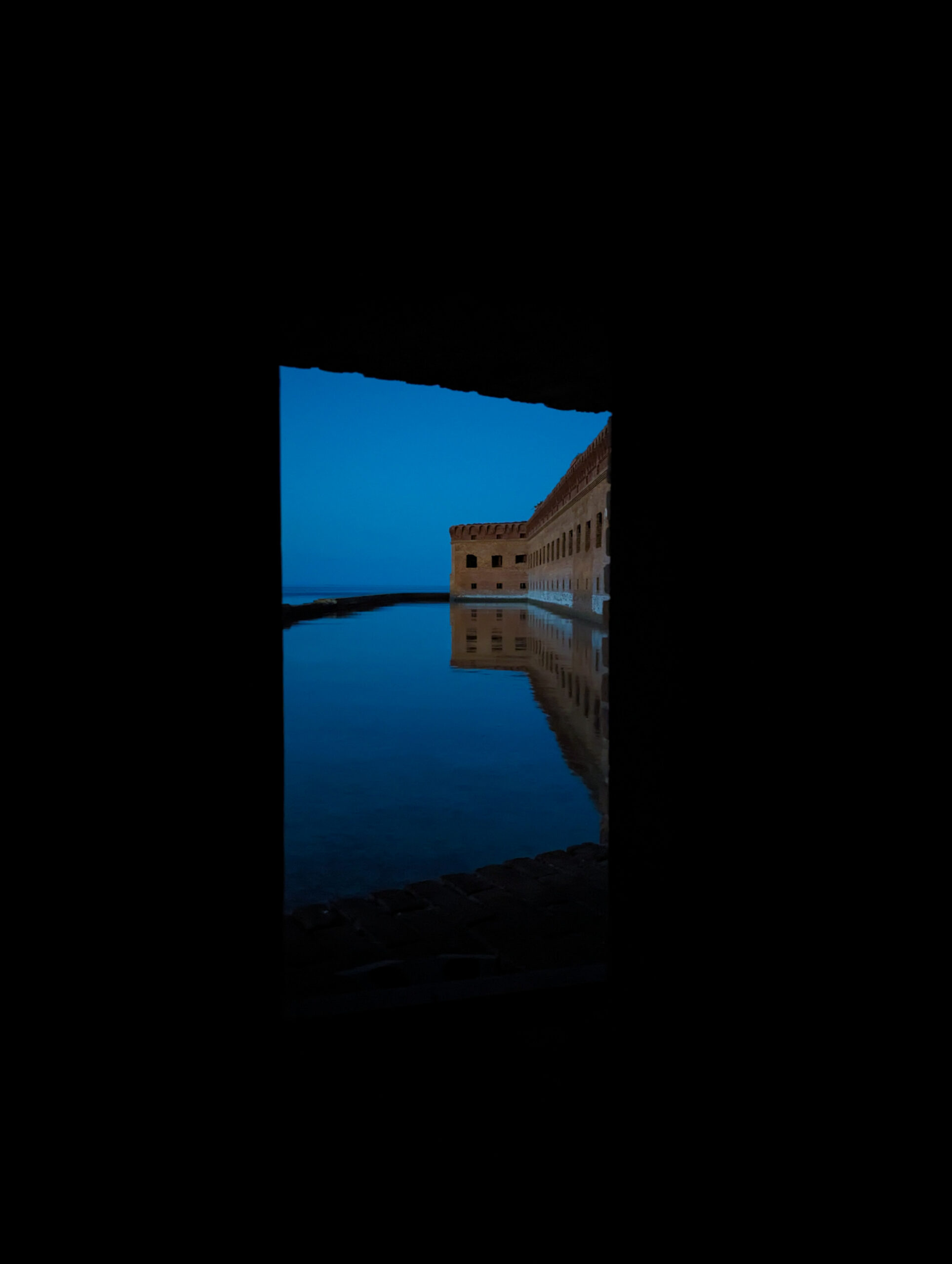

At the NPS office, we collect our treatment gear, pile into the truck, and head to Green Cay and the park boat Le Tigre. Most of the trips out to Buck are in some pretty good swell. Saint Croix is constantly windy as the easterlies or trade winds are usually ripping through here. On our journey out to Buck, we are heading almost directly east, so right into the wind and waves. Turtle watch is important since a lot of turtles are in the area and especially at this time in the season they will be mating on the surface. We skirt around the east of the island and enter the northern lagoon that is protected by a barrier reef.

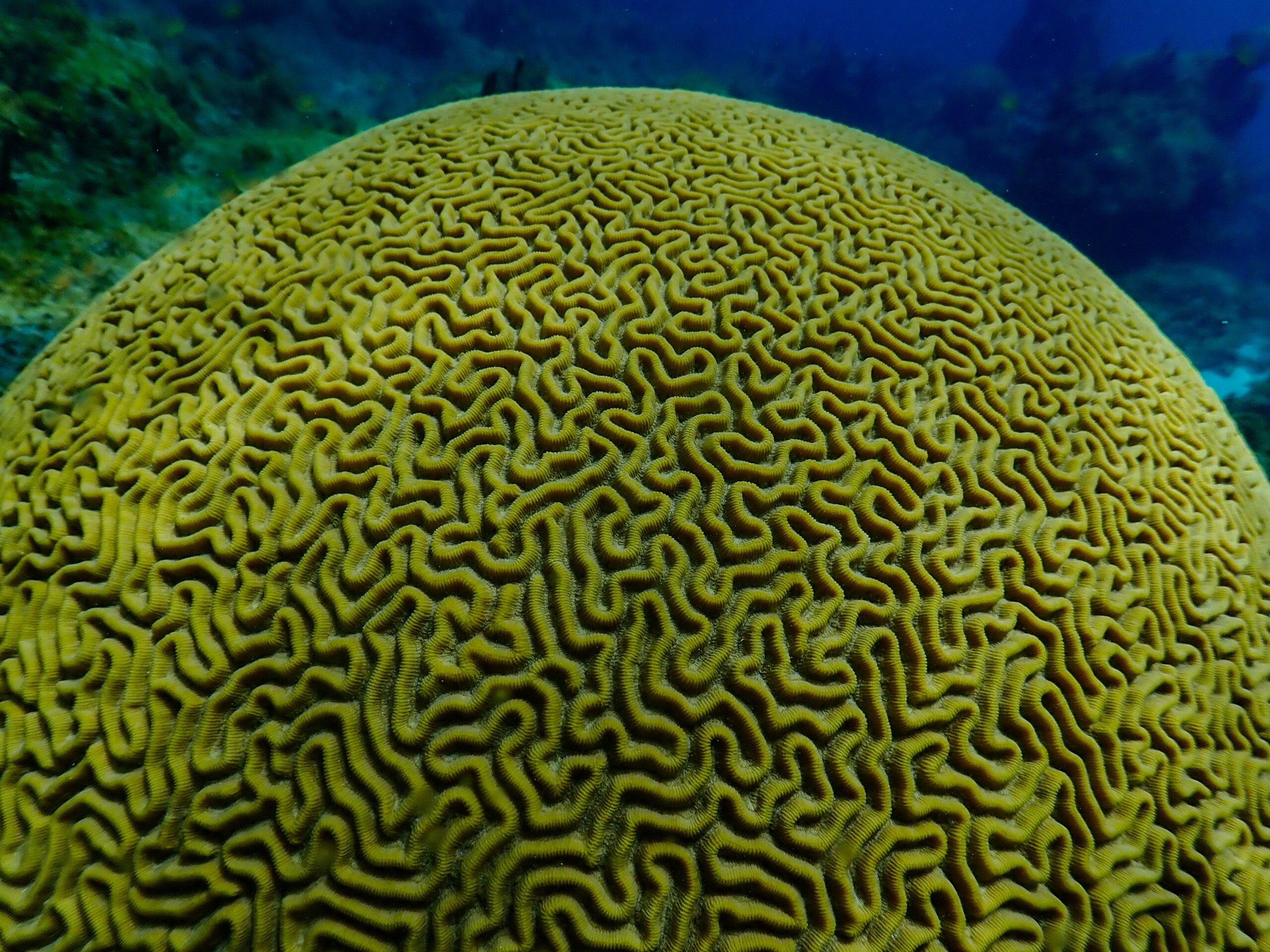

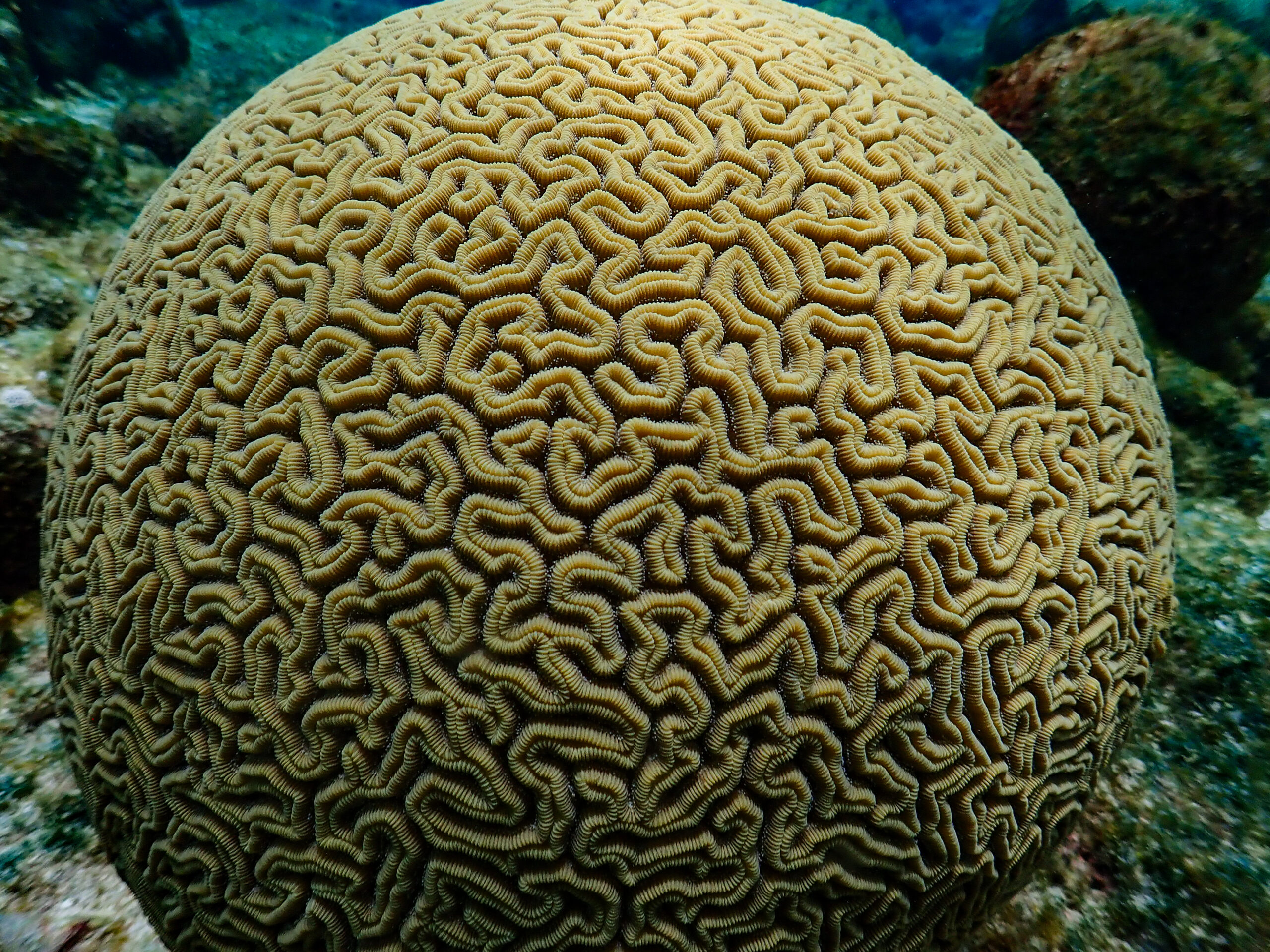

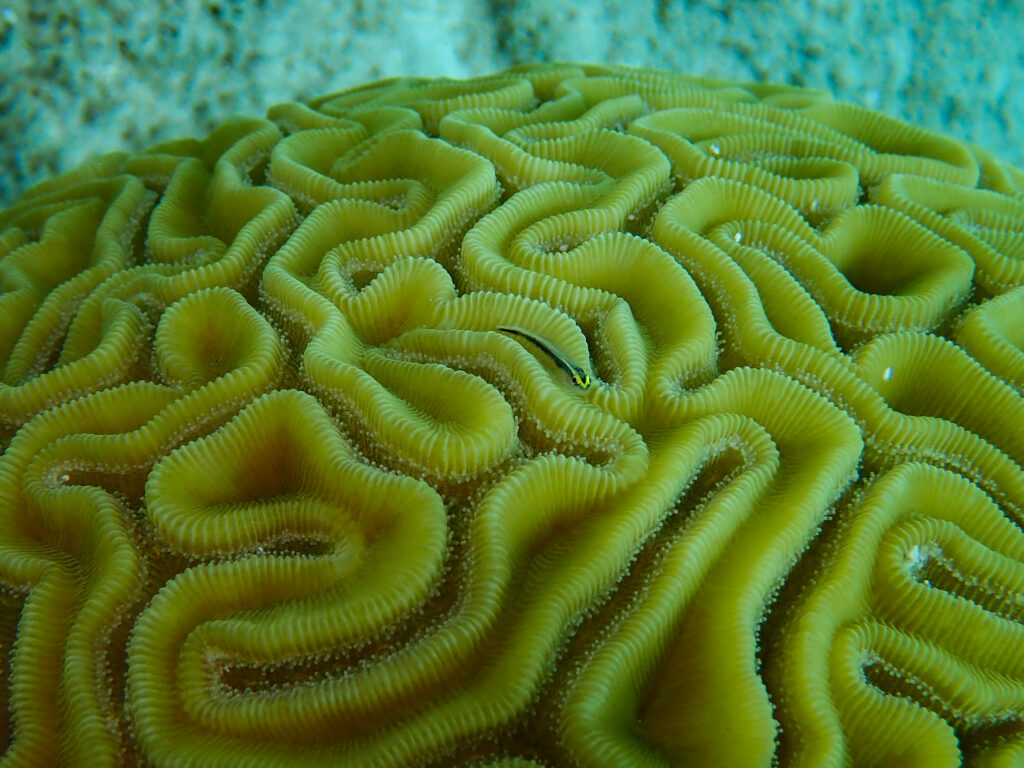

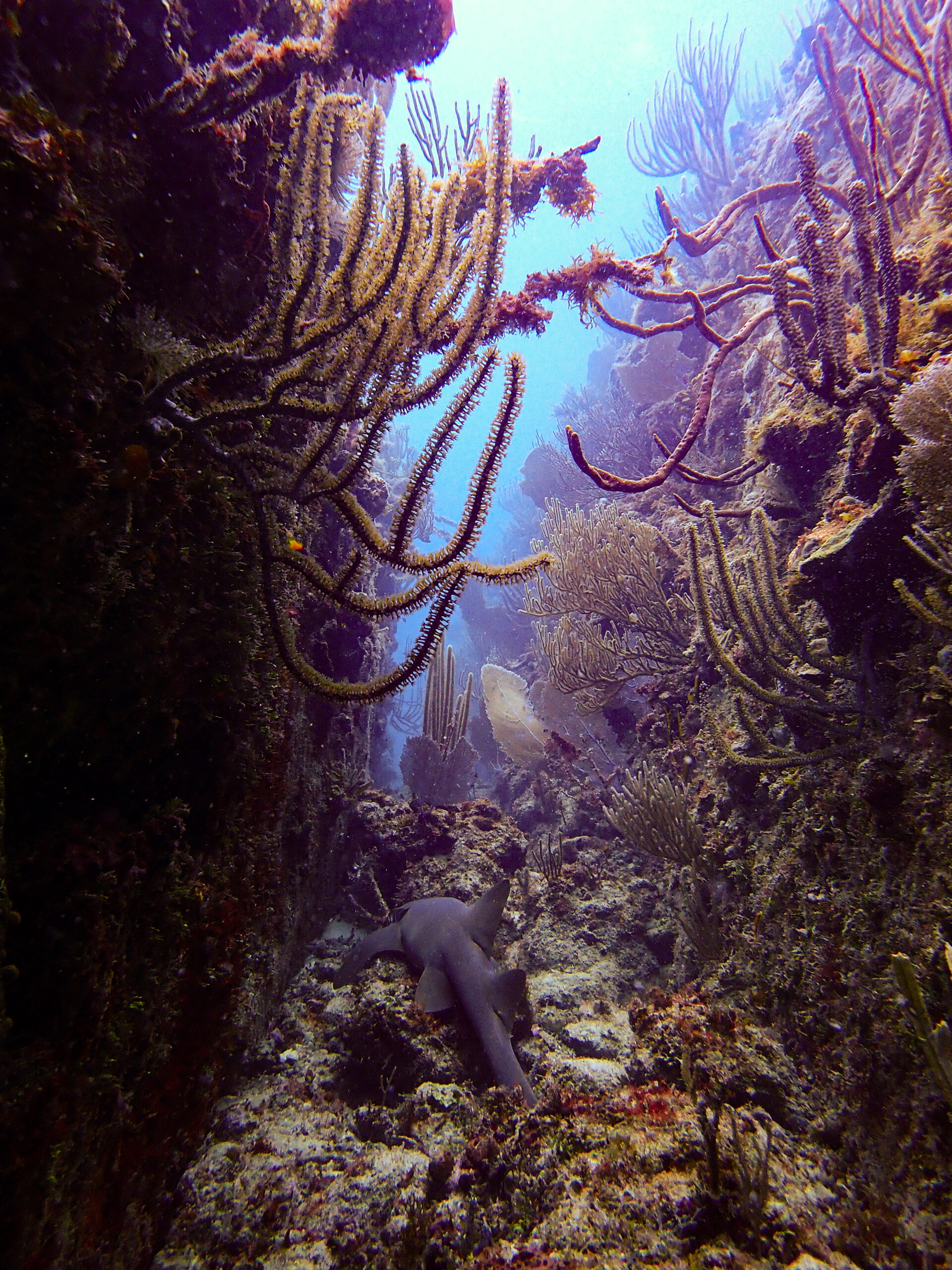

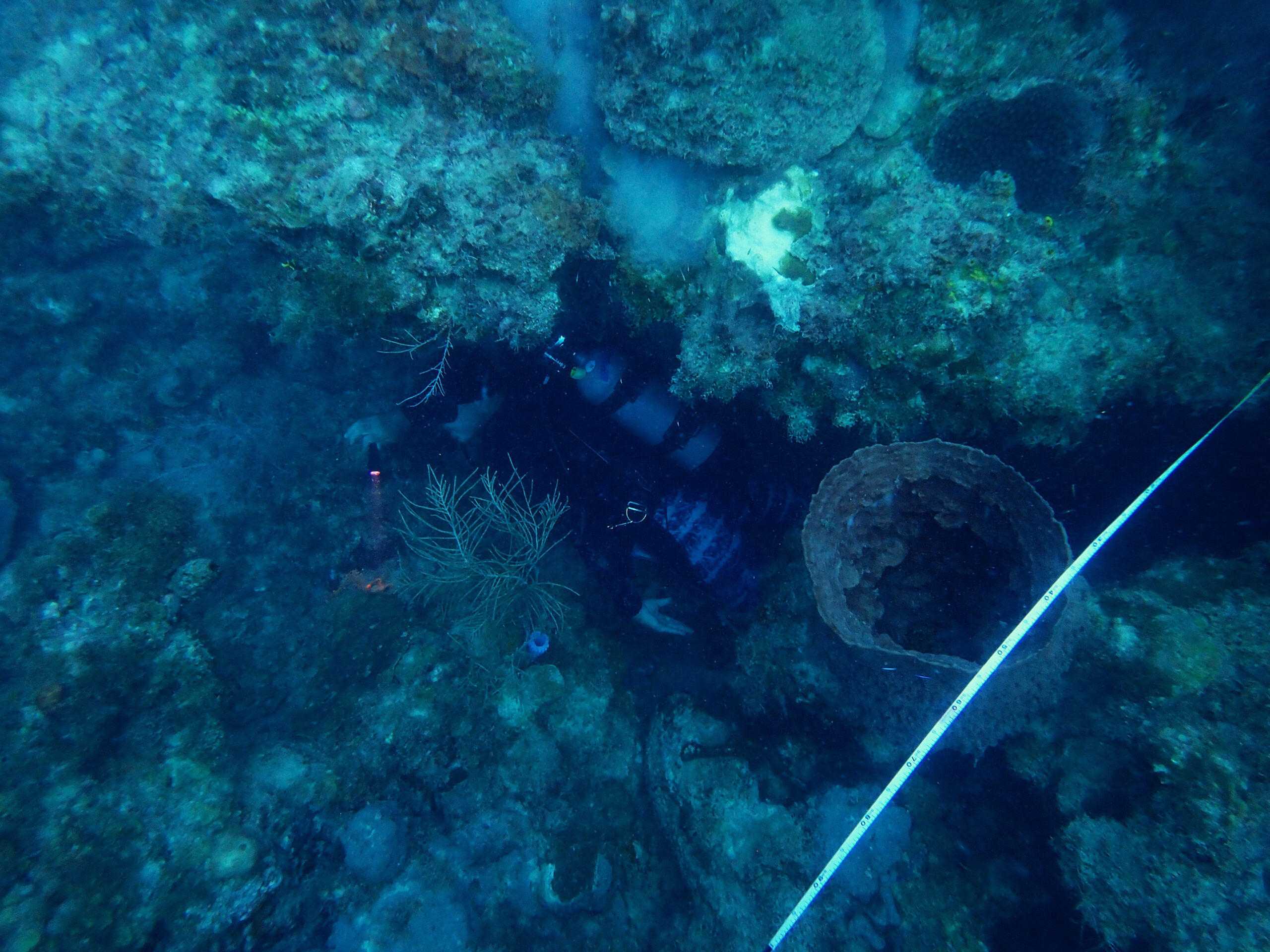

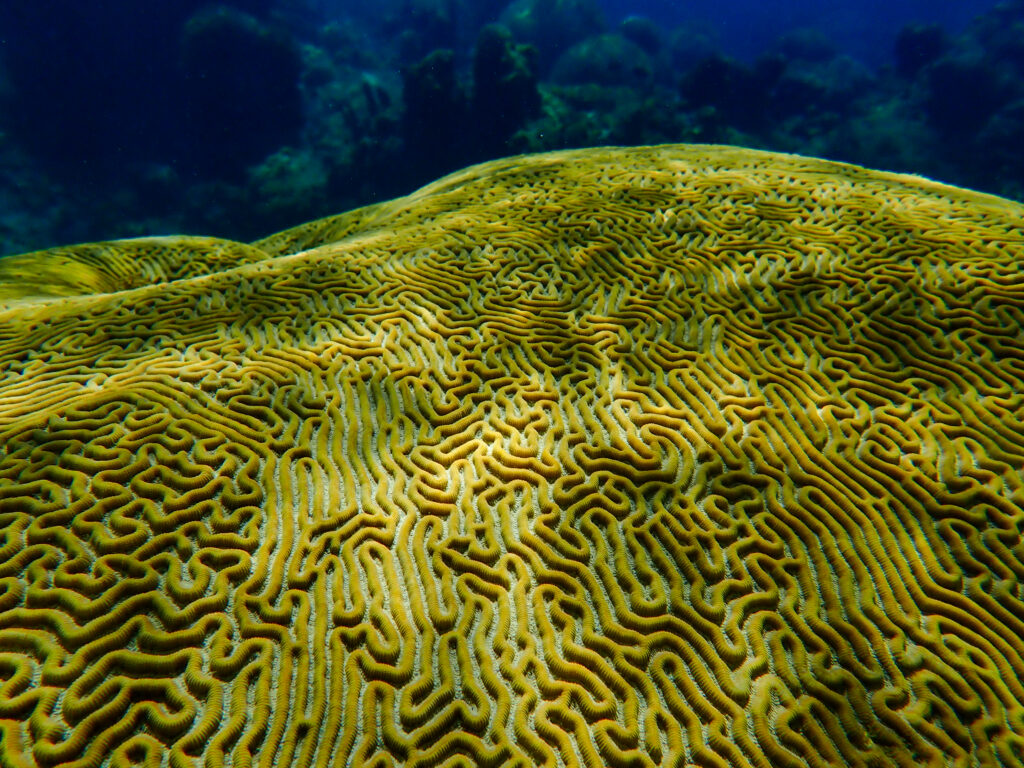

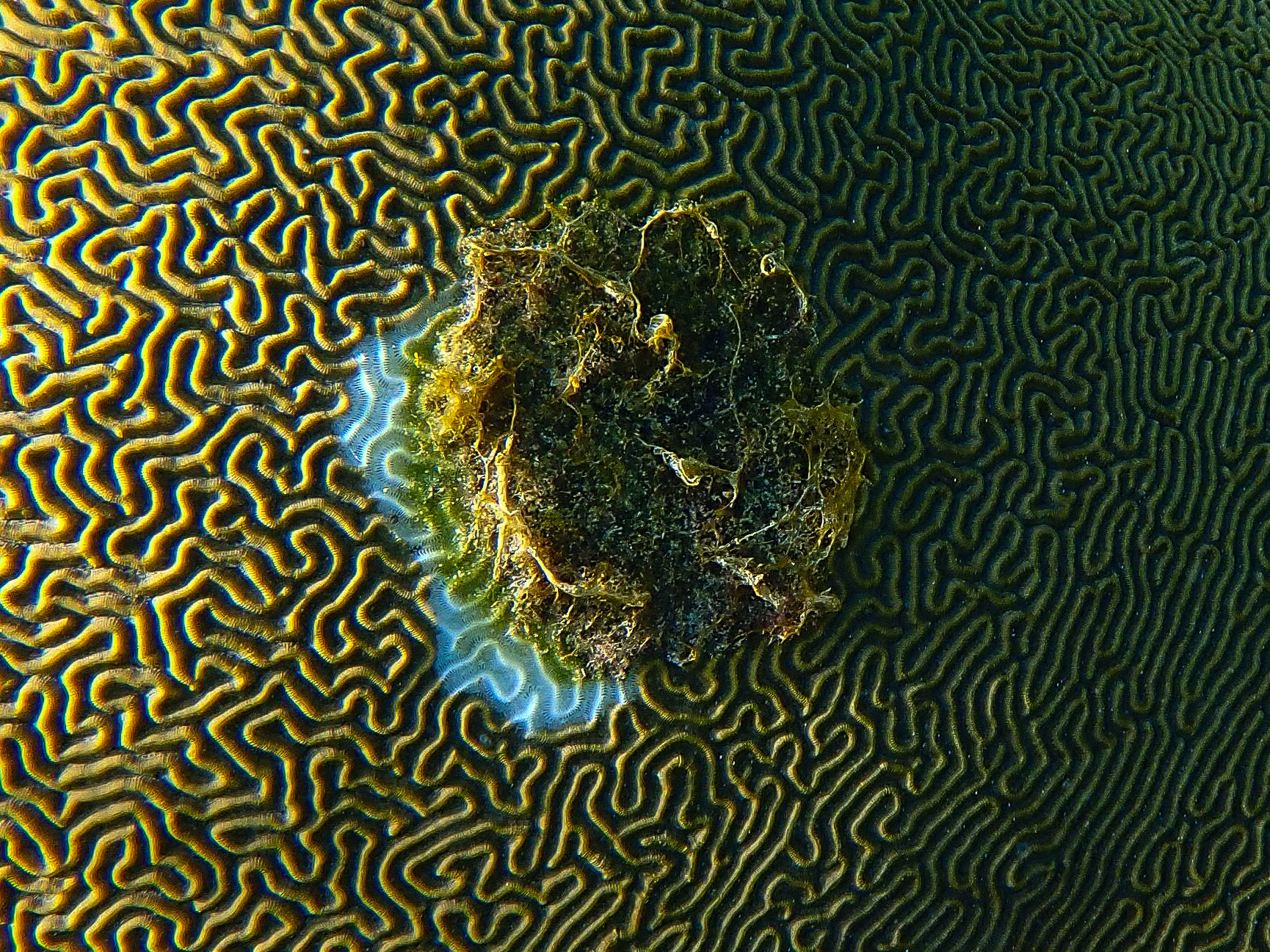

Okay, I know I’ve said every location so far has had amazing visibility but this one might take the cake. This lagoon is a popular snorkeling and diving site, and where the NPS has been doing the most coral treatment. The site we are focused on today is called Brain Garden. I dive with Rico so he can show me how best to apply the paste and identify the disease. The antibiotic paste is a mixture of amoxicillin and Base2B, which resembles coral mucus. The paste is applied on active lesions creating a barrier between the dead skeleton and live tissue. It is applied underwater with caulking guns. Most corals we will treat at this site will be brain coral species as they are susceptible to SCTLD. It is pretty clear when you find active lesions. On a coral colony, you can see live tissue and then a defined edge where tissue transitions to a bone-white skeleton. You can tell it is a fresh lesion because the bare skeleton has yet to be colonized by algae. Soon, algae will start growing where there is no live coral anymore.

I just imagine I’m on the bake off and I’m piping something for Paul Hollywood, so it must be perfect. Unfortunately, it’s not as easy as it seems. We’re in shallow water and the sea state is rough from the constant wind. This means we’re getting pulled back and forth through the water with the wave action. The paste will immediately be lifted off the coral with the current if it isn’t applied with pressure. My first attempt leaves a lot to be desired. I’m getting pummeled by the swell and damselfish are bothering me and poking at the paste that is streaming from the coral. Okay, not great but pretty quickly I get the hang of it. We treat until we run out of paste, focusing on corals that have the majority of their tissue left, but I can’t help but give some of these devastated colonies a little line of protection to potentially give them a chance at survival.

For me, this dive is devastating. Coming from a land of old-growth forests, some of our most important habitats, where trees are 1000s of years old, I can’t help but see this as the loss of old growth at Buck Island. These brain corals grow at about 3.5 mm/year. When you see colonies that are 6 feet in diameter, do the math- they’re old. Brain corals can live up to 900 years. Here, they are being wiped out in months. SCTLD only arrived in 2021 and a lot of these elders around me are completely gone. It’s absolutely heartbreaking. I know nature is resilient, and maybe even brain corals will rebound here but still, it is hard to wrap my head around the loss.

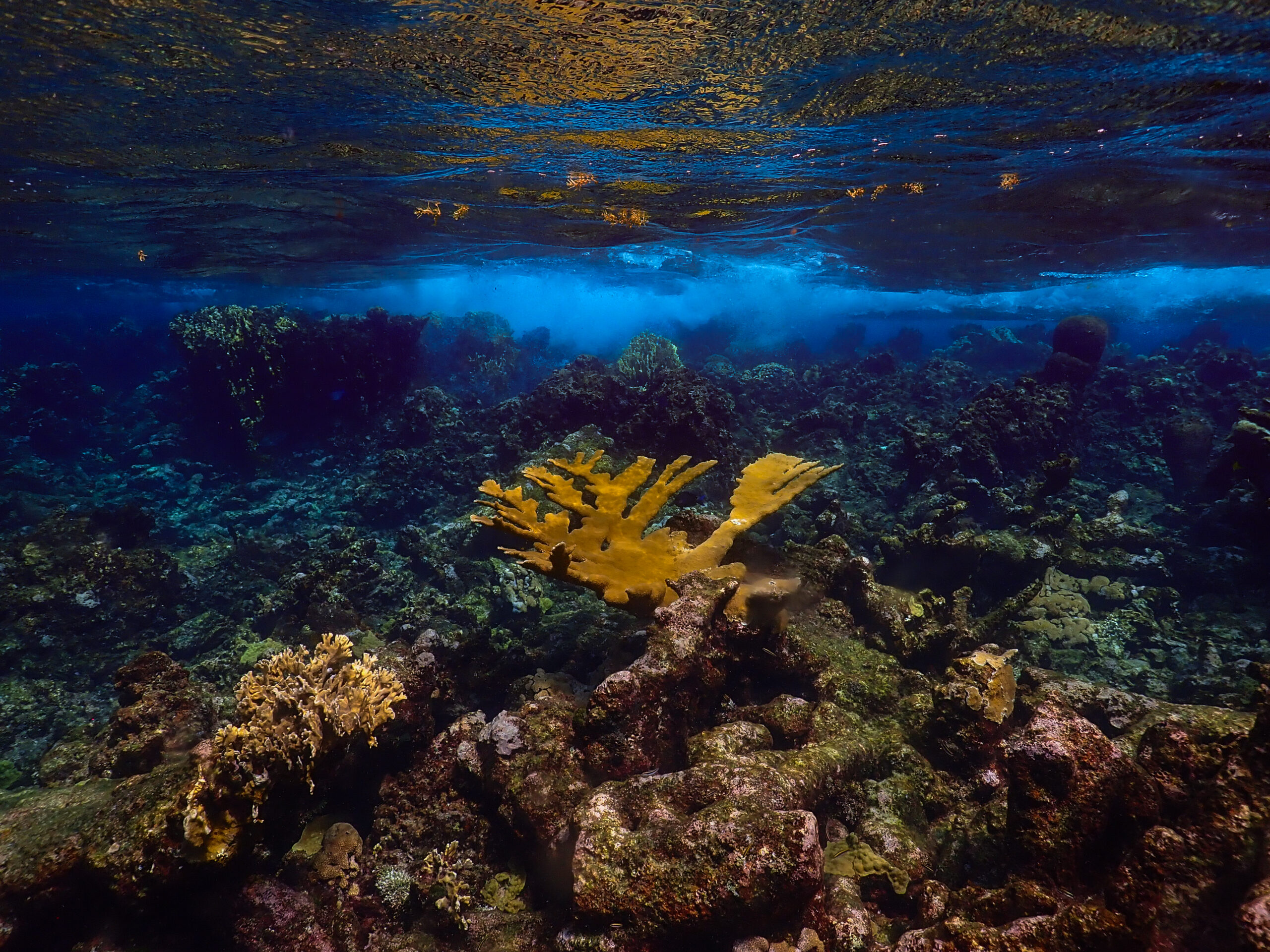

The next day, we are on the outside of the barrier reef on the north bar. It’s another tricky day of applying paste to brain corals with the constant swell running over the reef. Though it is also the first time I’ve seen large elkhorn coral, Acropora palmata, since being in the Caribbean. Some beautiful, giant, branching elkhorn. They’ve been hit by their own diseases, a big one in the 80s that wiped out 90% of the population. Then of course, while their branching structure provides amazing habitat, it doesn’t do well in hurricanes. The good news is that they are relatively fast-growing, compared to the brain corals and SCTLD does not affect them. I love watching the schools of blue tangs, the colorful stoplight parrotfish, the queen triggerfish, and the sea whips swaying back and forth in the current.

Tonight, I join the sea turtle nesting program on their beach patrols of Buck Island. Leatherbacks, Hawksbill, and Greens all nest on Buck. Globally, sea turtle populations have declined by at least 95% since the 15th century because of overexploitation. Here on Buck Island, Kristen and her team are working for the recovery of nesting sea turtles. The program is one of the longest-running sea turtle programs in the world, with over three decades of monitoring and rigorous data collection to assess the status of populations. On the island, endangered Hawksbill sea turtles have made a dramatic recovery, going from 12 nesting females in 1987 to over 500 more recently.

It’s a half night tonight so we are only going out from 6pm to around 11pm. We see some Green sea turtles mating at the surface on the way out. The team starts with a day patrol, checking out tracks to gauge turtle activity since the last visit. As we move down the beach, a line is drawn in the sand above the high tide line to keep track of old tracks surveyed and any new tracks that appear. These guys are experts at deducing activity from the turtle tracks. I learn Hawksbills make comma swishes with their flippers and Greens, look more like tire treads as they push together with their flippers moving through the sand. On this patrol, we don’t find any new nests, but Kristen’s team excavates an old nest and recovers two hatchlings still alive that are released into the water. Now it’s dark and we are using red lights to survey the beach. A couple of hours later, on the north beach, an old Hawksbill momma comes up to nest. Since she is not tagged the team is going to wait for her to dig her nest and then tag her. It takes her a while to find a suitable spot. We sit quietly in the dark. Once she starts laying, it’s lights on and all action. I guess turtles go into a trance-like state when they’re laying so they aren’t phased by the activity. Data is collected, she is tagged, measured and a biopsy is collected. I’m useless at this point because the turtle team has got it down, so I just get to enjoy the beautiful endangered prehistoric creature. She finishes laying, covers her nest, camouflages it, and heads back out to sea. Congratulations turtle momma!

On our way back to the boat we find another Hawksbill who had just laid and is heading back out to sea. So cool! I’ve never done anything with turtles before, so this whole experience was very exciting for me. Kristen and her team of interns and community youth are legendary and such hard workers, coming out multiple days a week 6pm to 6am taking care of nesting sea turtles on Buck Island. Thanks for letting me tag along.

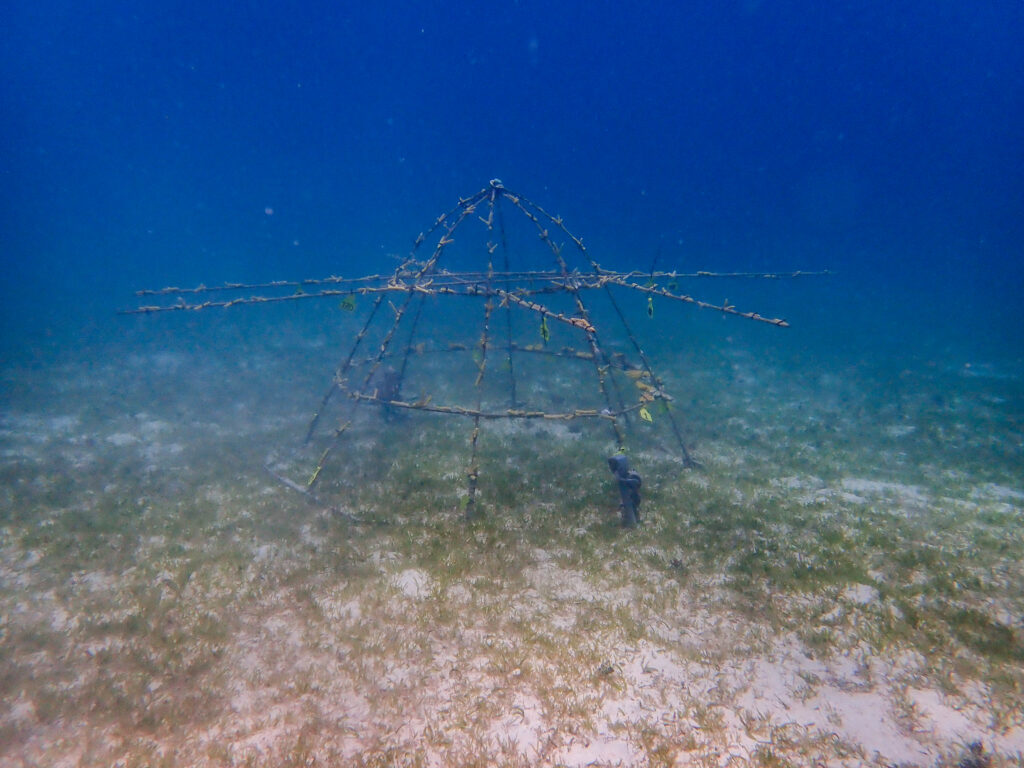

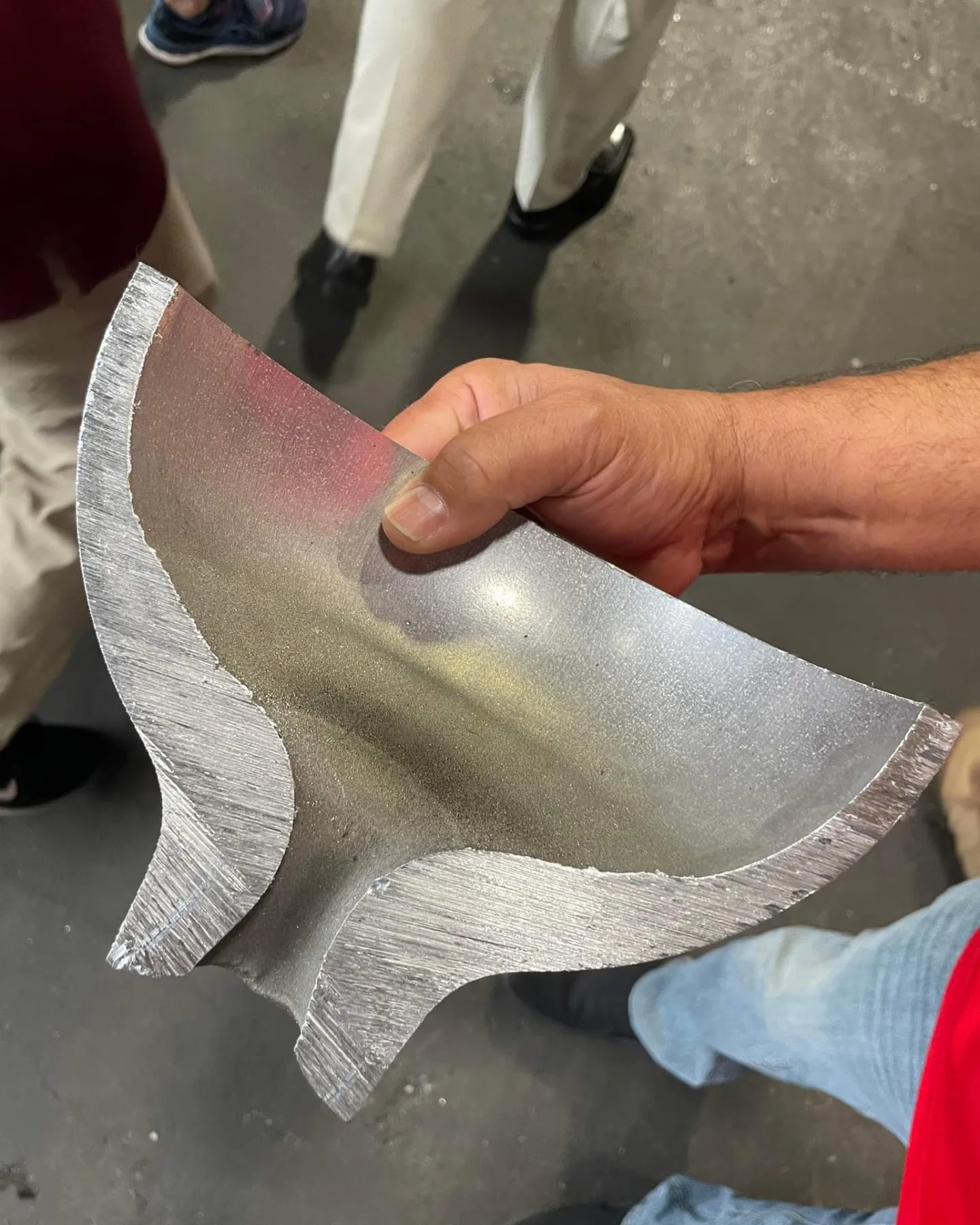

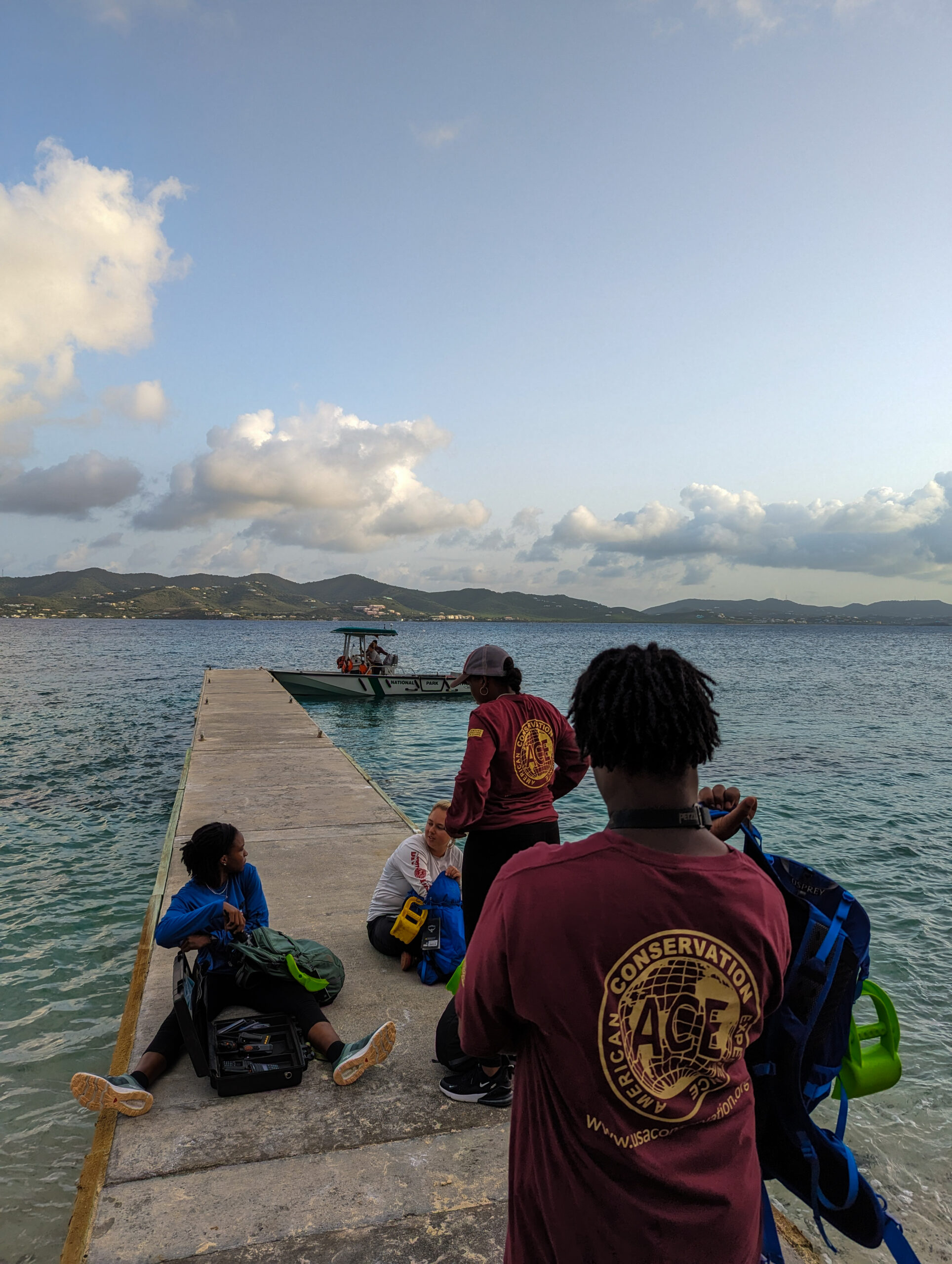

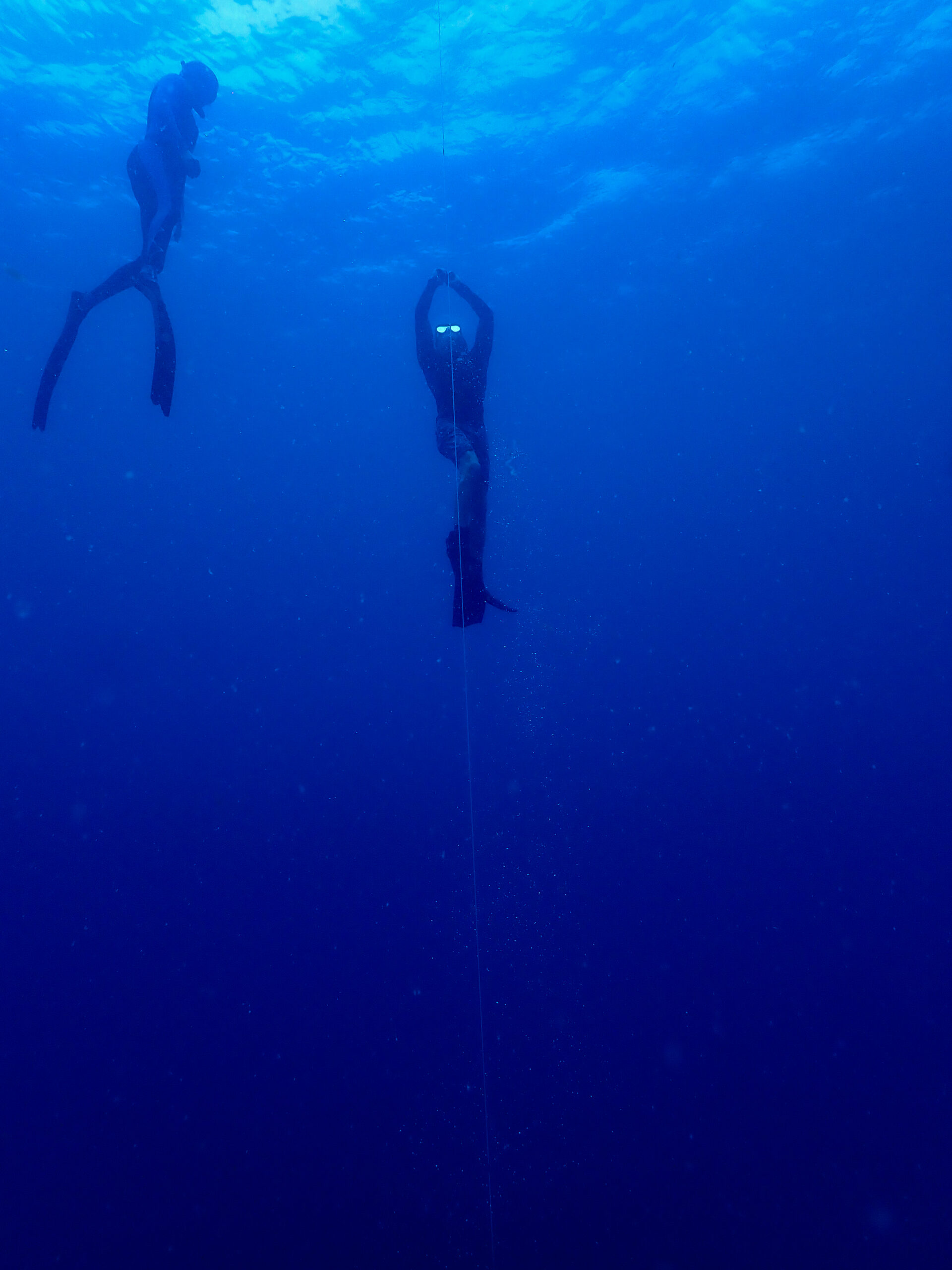

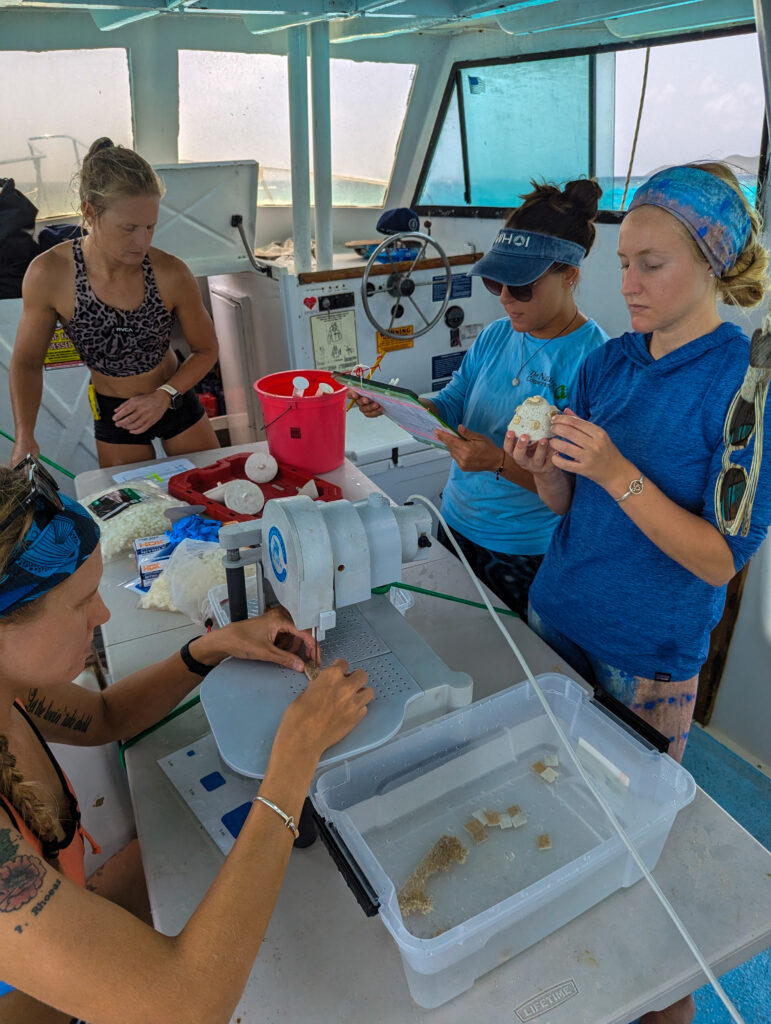

Nearing the end of my time on Saint Croix, I get the chance to join The Nature Conservancy (TNC) coral team for a joint coral fragmenting mission with the NPS. TNC has partnered with the national park to do coral restoration at Buck Island. One of the freedivers I met over the weekend, Alex Gussing, Coral Conservation Coordinator for TNC, explains the project. They have pieces of Acropora palmata growing on tables at their nursery in the lagoon at Buck Island. We will be taking those larger pieces and fragmenting them into small pieces with a bandsaw on board the boat. These fragments from the same genotype will be glued to a cement dome. What TNC has found is that the small fragments with the cut edges grow more quickly and after a couple of months all of the little fragments will have fused together. Basically speeding up coral growth and boosting restoration, these corals can then be placed back on the reef. They are also experimenting with different sizes of fragments to see what works the best. It’s a full day on the boat with a cool crew doing cool work. I get to try a range of jobs from gluing the fragments to the cones, using the bandsaw to fragment, and then swimming the fragmented coral cones back out to the nursery site. I will be interested to check back in a couple of months to see how the fragments are doing in the nursery. Thank you TNC for inviting me out to join you!

Finally it’s my last day of coral treatment with NPS here on Saint Croix. We take the park boat Kestrel out and visit a new site for me. Since it’s in about 40 feet of water, there are some different species than the ones we’ve been treating in the shallow lagoon. A lot of big star coral colonies, another species highly affected by SCTLD.

BUIS has been a busy 10 days full of coral conservation work–all new experiences for me. I am inspired by the coral heroes in the NPS and TNC who are working hard to protect threatened ecosystems on Saint Croix and in the Caribbean. It has been a pleasure to work with and learn from so many amazing ocean advocates in my time at Dry Tortugas, Saint John, and Saint Croix. I’m sad to leave the Caribbean but am excited to travel halfway across the world to my next national park on Molokai, Hawaii. Thanks again Kristen, Rachel, Rico, Katie, and Nicole for including me in your dive work at Buck Island. And of course, big thanks to the OWUSS and the SRC.