In 1917, Alfred Mayer, pioneering marine biologist and zoologist of the Carnegie Institute, began what is now the world’s oldest continuously monitored coral reef transect. Ahead of his time, he performed one of the first robust quantitative reef surveys, with his most notable effort and lasting legacy being the Aua reef transect in Pago Pago harbor, American Samoa.

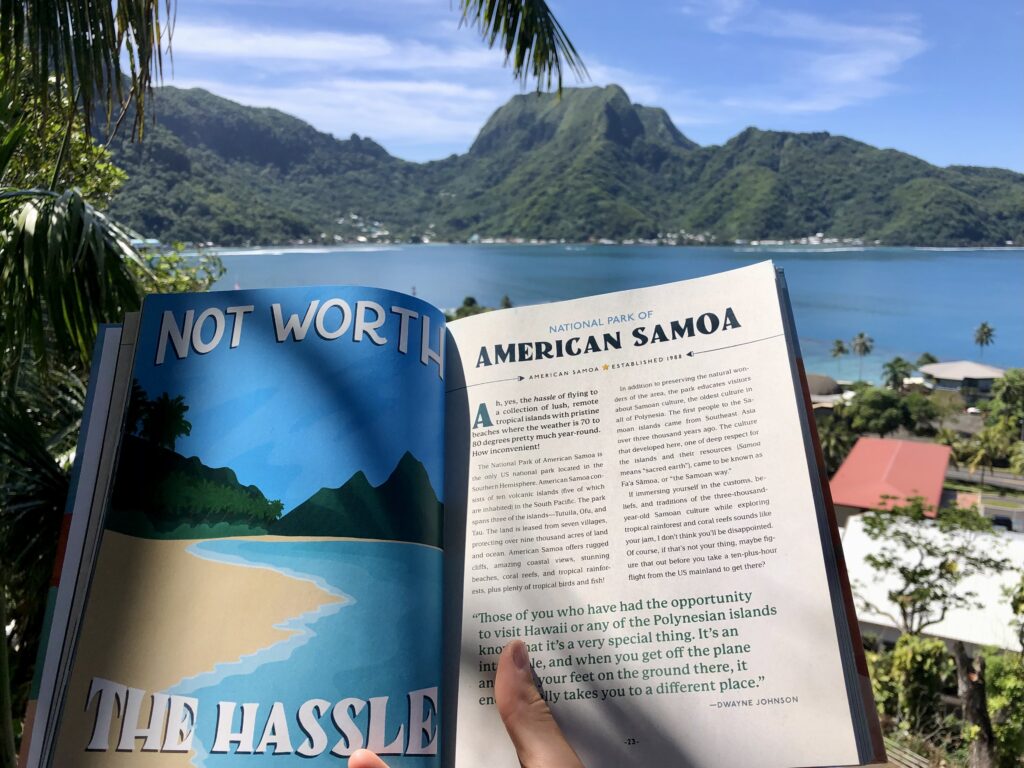

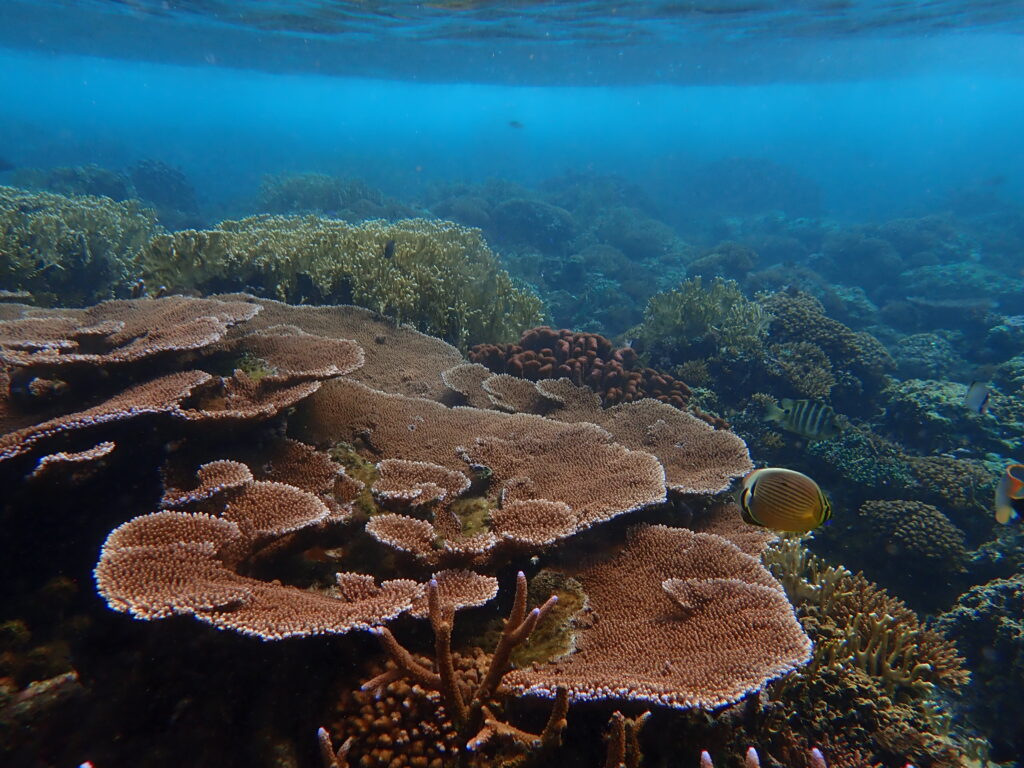

Healthy shallow reefs line the Pago Pago harbour on the island of Tutuila, American Samoa

Inspiring modern-day scientists to continue in his footsteps, Dr. Alison Green and Dr. Charles Birkeland (who I had the great pleasure of working with and meeting during my Master’s at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology) spearheaded regular surveys of the historical transect, through to its 100th anniversary, and into the present day. Remarkably, these reefs continue to thrive despite being subject to rapid development (as American Samoa transformed from a sustenance to market economy, developing major ports, industrial fishing, large-scale dredging, and wastewater disposal within the main harbor). 1995 surveys revealed that approximately 95% of the corals had been severely degraded following these activities. However, over time, the outer reef within the harbor has flourished. It now hosts an even greater abundance of corals than the pristine community observed by Meyers in 1917 – a truly resilient reef.

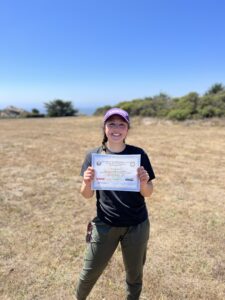

A silver plaque marks the world’s longest continuously monitored coral reef transect – a photo that I shared with colleagues back at KAUST, including Dr. Alison Green, who contributed to the areas continued monitoring over several decades

With the guidance and friendly company of my colleague, Valentine Vaeoso (and permission of the local village), I was able to visit this historical site (located only steps away from the main road), do my own informal survey of the area, and take in perhaps one of the only places in the world where you can have a roadside pizza delivered while snorkeling one of the most spectacular shallow reefs sites I’ve laid eyes on.

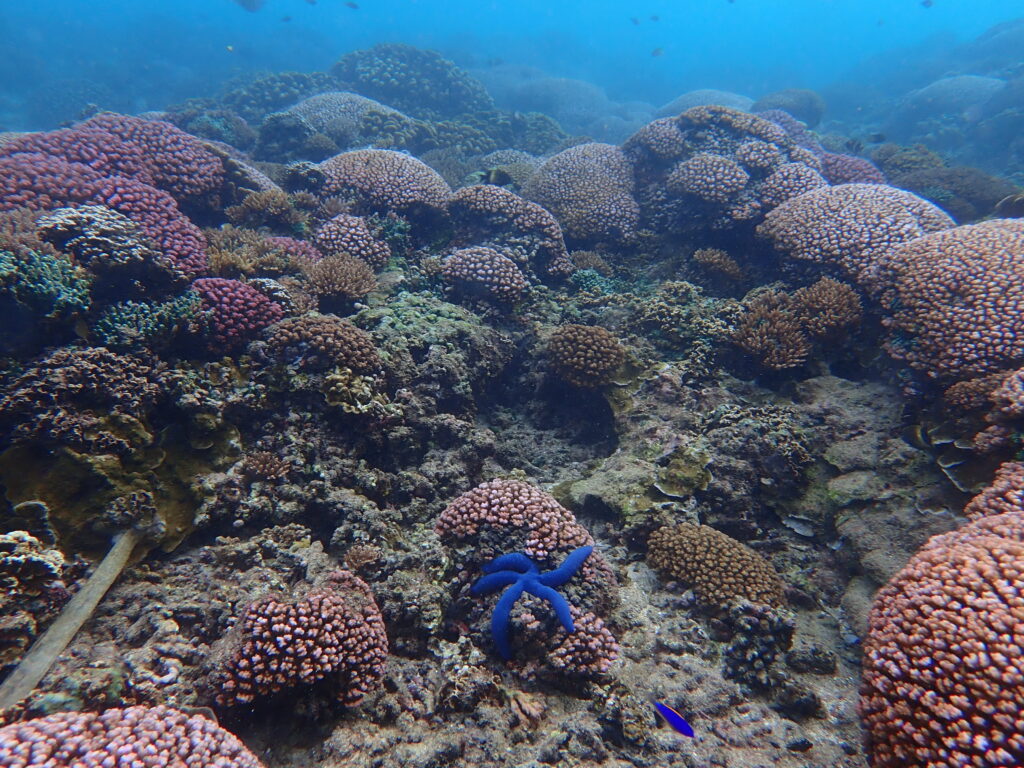

Underwater, you would never guess that you are only meters from the nearby village, roads, construction sites, and super markets

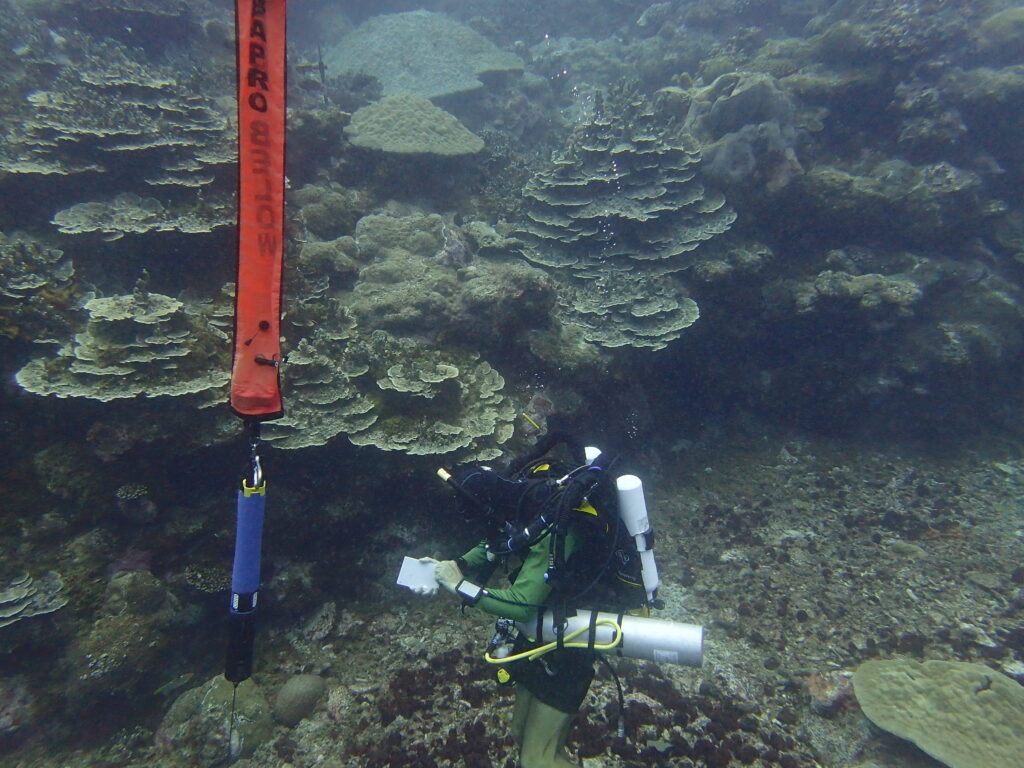

With field operations up and running, Marine Ecologist Dr. Eric Brown, Marine Biological Science Technician Ian Moffitt, and NPS Intern Valentine Vaeoso and I set off for a week and a half of fieldwork in fulfillment of the annual Pacific Island Inventory & Monitoring Network subtidal surveys. Developed by Dr. Eric Brown during his Ph.D. dissertation, this standardized protocol is now widely used throughout the Pacific National Parks. A highly experienced ecologist and meticulous teacher, I was excited to work alongside Eric on this project and learn more about his path through academia into the National Park Service.

Marine Ecologist Eric Brown, Marine Biological Science Technician Ian Moffitt, and I, immediately before a survey dive, in front of the steep walls of Pola island

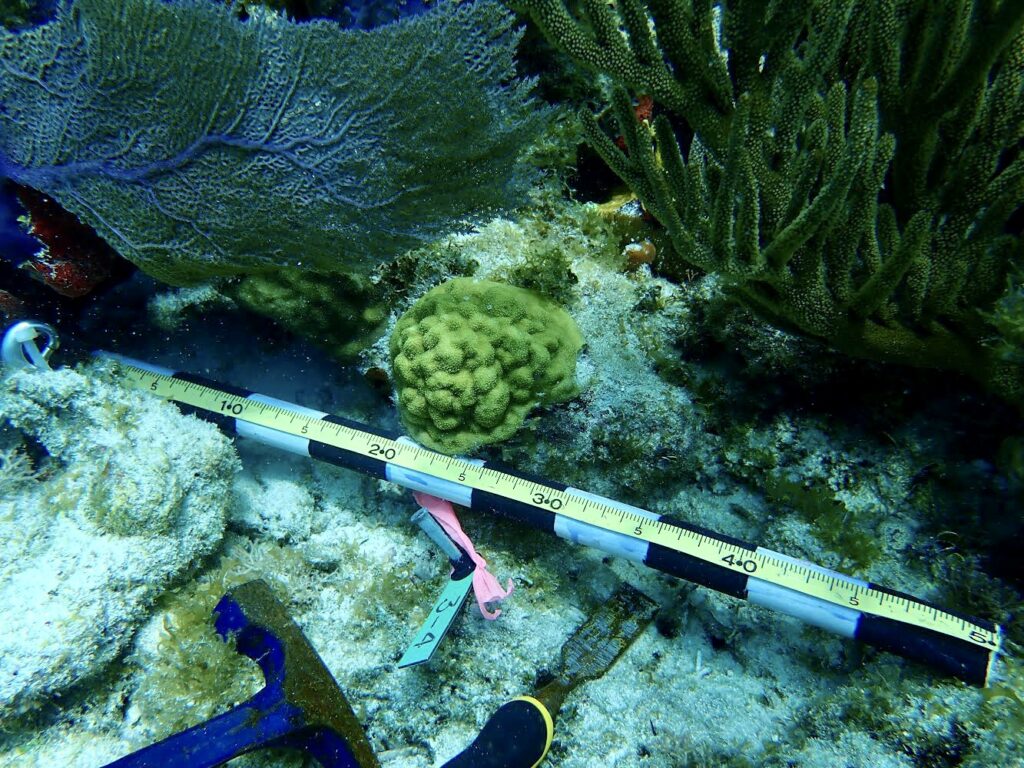

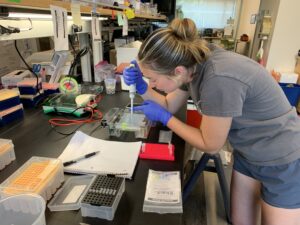

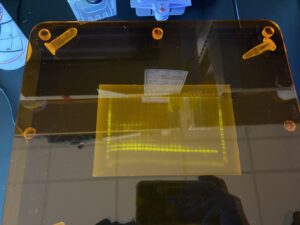

In a nutshell, the Pacific Island Inventory & Monitoring Network subtidal surveys are comprised of four key aspects which monitor marine Vital Signs (i.e., indicators of physical, chemical, biological processes, and factors selected to represent the overall health of natural resources): fish surveys, benthic surveys, rugosity measurements, and water quality. Ian took the lead for fish surveys during each dive, identifying and sizing each individual fish. I followed closely behind, taking benthic photos every meter (an excellent opportunity to continue optimizing buoyancy control in different environmental conditions while carefully navigating fragile shelving corals and deep cuts in the reef). In his element, Eric followed behind, taking rugosity measurements on temporary sites – a tedious task that involves inching along the transect with a small metal chain, laying it across each nook and cranny of the reef, often having to wedge himself under shelves and deep holes (in a bulky rebreather to boot!). Water quality sampling duties were shared by all during surface intervals and involved filtering water samples for nutrient analysis.

Bethic photos are taken at each meter along the transect. Photo: Ian Moffitt

Marine Ecologist Eric Brown deploys a water quality sensor during surveys, alongside an impressive wall of coral

The reefs we surveyed are in generally good health – some showing damage by hurricanes but promising signs of recovery. Although NPSA has a high level of species diversity, it is known to have lower marine biomass compared to other parks, which may be due to fishing pressure, poor water quality in certain areas, the 2009 tsunami that altered reef structure, a Crown-of-Thorns (CoTS) outbreak from 2011–2015, and changes in climate leading to bleaching events. Nevertheless, global anomalies continue to thrive here, such as some of the world’s largest corals (including large Porities corals measuring up to 22 meters across, 8 meters tall, and a circumference of 69 meters). Estimated at between 420–652 years old, it is evident that the islands of American Samoa have ideal conditions that support hearty, long-lived, and resilient corals.

An example of one of the massive corals found in American Samoa. Photo: Wendy Cover/NOAA

Topside, I was treated to several marine-related activities to polish off my time in American Samoa. During our last field day, as we were bringing the research vessels back around west to the main harbor in Pago Pago, we encountered humpback whales! Two adults and one calf cruising the surface. My very first encounter with whales – I had to try my hardest not to squeal with excitement in the presence of these beautiful giants, as we followed the group from a distance while Eric narrated details of their behavior and occurrence in the area.

My first time whale watching during the final day of field work – I did not dare take my eyes off of the horizon

My last dive in American Samoa also treated me to a trip “bucket list” species I had yet to spot – the peculiar Hemitaurichtys polylepis

I also joined many of the NPSA staff for a biweekly paddling practice, during which we used traditional Samoan 6-person canoes to race around the harbor. A passion shared by many and the focus of much friendly competition throughout the year on the island, I was incredibly excited to score a seat on one of these boats and had a blast trying to keep up with the pacers rhythm while simultaneously trying not to tip the deceivingly unstable, narrow, canoe. That afternoon on the water gave me a small glimpse into the pride and camaraderie generated by this culturally significant sport – and I was warmed by the celebratory high fives and echo’s of a job well done by all as we finished practice.

Members of the NPSA team, from the Superintendent Scott Burch, to the Marine, I&M, Interpretation, and Terrestrial crew got together to paddle in traditional 6-person Samoan canoes on the harbour in front of the office

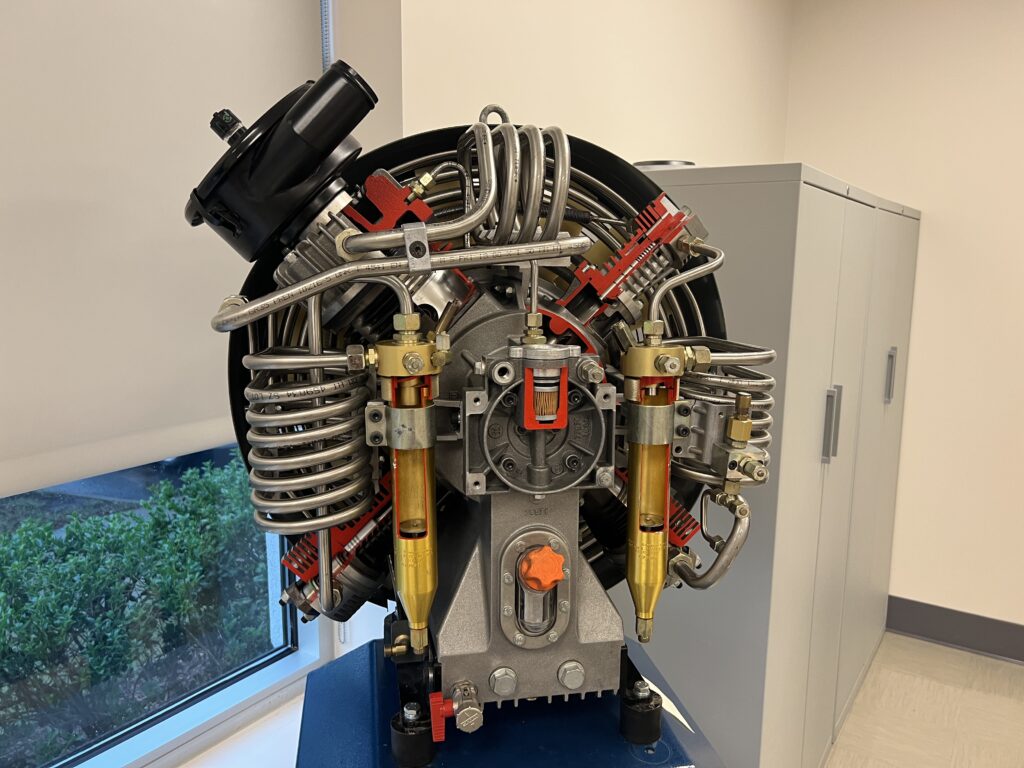

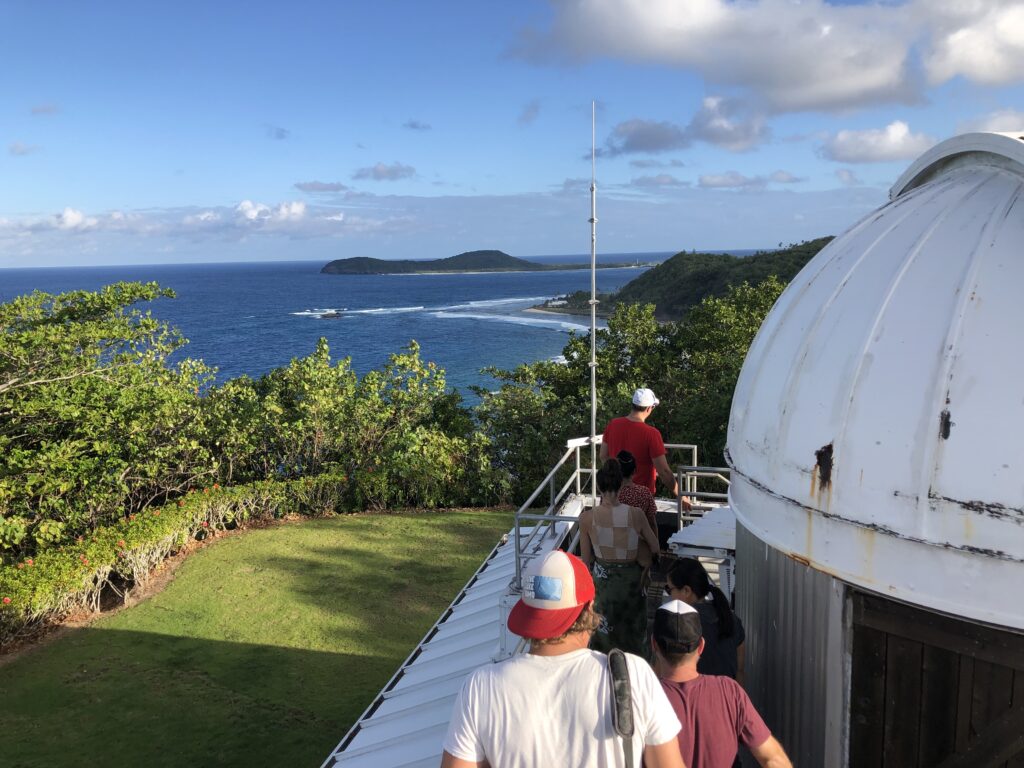

In addition to pristine, larger-than-life reefs, American Samoa is home to some of the best air quality across global population centers. As part of NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory, the American Samoa Baseline Observatory collects data to address research on three significant challenges: greenhouse gas and carbon cycle feedbacks, changes in clouds, aerosols, surface radiation, and recovery of stratospheric ozone. Sitting atop the scenic northeastern tip of Tutuila Island, at Cape Matatula, the Coconut Point crew (Ian, Norelle, Taylor, Adam, Joe, Alisha, Casey, Max, Monyca, and Bob the Owl) took a trip to the observatory during my last weekend on the island, for a tour hosted by Observatory Operator Gregory Freidman. One of only four facilities worldwide (Alaska, Hawaii, American Samoa, and the South Pole), these high-tech pieces of equipment aim to generate the best possible information to inform decisions on climate change, weather variability, carbon cycle feedback, and ozone depletion.

A souvenir to take home from NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory, the American Samoa Baseline Observatory. A sample of some of the finest air the world has to offer within global population centers

Touring NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory American Samoa Baseline Observatory

Although my visit to NPSA is the longest I will spend in any park this summer, three weeks pass quickly – and I am left with countless reasons to return one day. My first time in the South Pacific Islands left much to explore – including the Manu’a islands, Rose Atoll, the giant Porites, and the neighboring Independent State of Samoa. I look forward to returning in the future and reuniting with new friends, whenever that may be.

The “hassles” of getting to this spectacular park were greatly eased by the support of the NPS team and new friends. Fa’afetai, Taylor, for graciously letting me crash at your new apartment just moments after returning from two years on the mainland. Thank you to Ian and Norelle for making sure I was always well-stocked with groceries, (and to Ian for suffering through a weekend shopping trip as a try to decide which patterned shirt out of hundreds to bring home with me), for Norelle for showing me where to find the best local treats. Thank you Tine for keeping days on the boats lively with tunes and generously upgrading my daily trip to the office from local buses to the open back of your truck, taking in the view on our daily commute. And lastly, thank you to Eric Brown for sharing your experience with me, being the voice of reason during fragmented field days, and hosting me at NPSA.

Against all odds – this team made it into the field! Thank you Tine, Eric, and Ian for welcoming me into your team, showing me around the island, and persevering across all road bumps we encountered to make my time at the park a great success

Thus far, this internship has been a whirlwind of new experiences, through which I have learnt just how capable I am of integrating into a new environment with the added pressure of a short timeframe and varying roles and responsibilities. Each place I will visit, from New York to Hawaii, and everywhere in between, is an entirely new experience for me – made possible by the unwavering support and encouragement of the NPS Submerged Resources Center and OWUSS. If given an opportunity like such, be sure to bring your energy, enthusiasm, and plenty of sunscreen.