In the age of Instagram influencers and travel vloggers, it is now easier than ever to share one’s opinion with the virtual masses – critique, praise, compliments, or otherwise. Subsequently, these virtual advertisements and informal ratings often influence where we eat, travel, live, and work. With millions of visitors each year, it is no surprise that the US National Parks have their own archive of online reviews numbering in the thousands.

Mixed amongst glowing reviews about family trips, backcountry getaways, and tropical park paradises are the infamous one-star Google reviews – from visitors who just weren’t having any of it. Forever memorialized by Amber Share, designer, and illustrator, in her best-selling book “Subpar Parks,” she has created eye-catching posters poking fun at the best of the worst – America’s Most Extraordinary National Parks and Their Least Impressed Visitors. Arches National Park? Looks nothing like the license plate. Zion National Park? Scenery is distant and impersonal. Sequoia National Park? There are bugs. And they will bite you on your face.

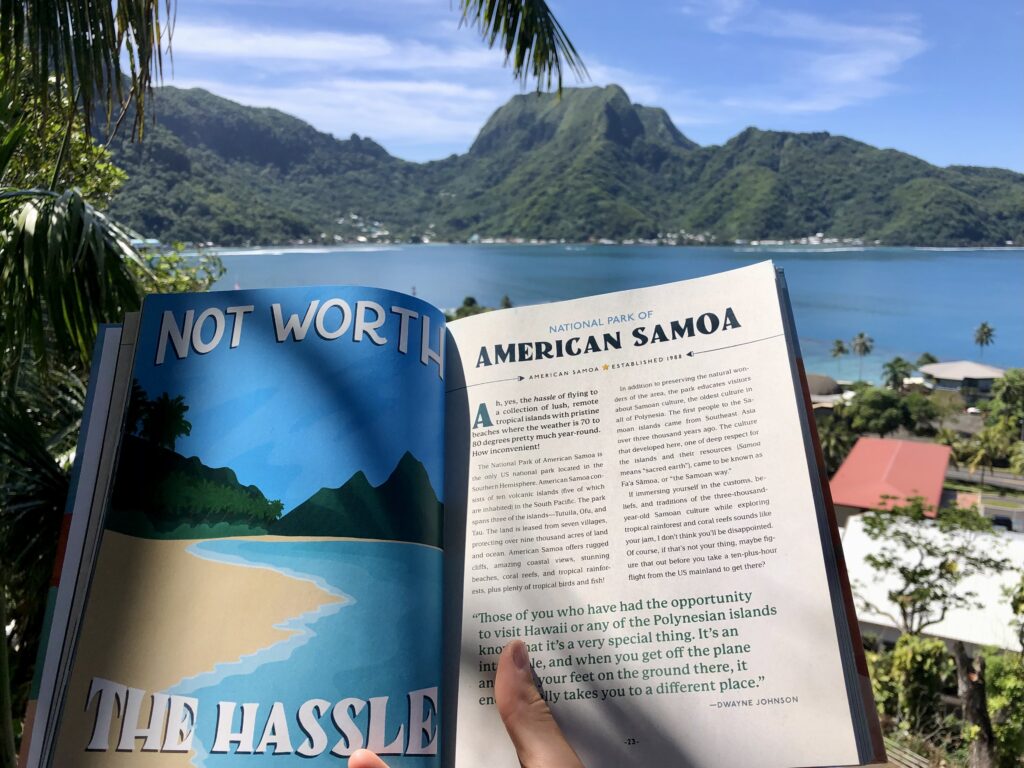

Driven by curiosity, I flip through a copy of Subpar Parks that lives on Marine Ecologist Dr. Eric Brown’s coffee table. I skim directly to the page featuring the National Park of American Samoa to see what I’m up against. “Not worth the hassle”? We will see about that…

Subpar Parks: America’s Most Extraordinary National Parks and Their Least Impressed Visitors. These posters-turned-book poke fun at real one-star Google reviews left by visitors who did not take to the stunning vistas and pristine waters of American Samoa

I arrive in American Samoa with momentum, ready to jump into fieldwork. I am here to join Marine Ecologist Dr. Eric Brown and Marine Biological Science Technician Ian Moffitt – with the support of boat operator and NPS intern Valentine Vaeoso for the annual Inventory and Monitoring surveys. Having been on the road now for several months, I feel comfortable in the routine of quickly settling in, integrating into a new field team, and conducting fieldwork daily. On top of it all, I can’t wait to lay my eyes on Tutuila’s spectacular reefs.

Shallow reefs just below the surface in the main harbour of Pago Pago, the capital of American Samoa, located on Tutuila island

Despite the entire team’s desire to get back in the water and start chipping away at surveys as soon as possible – for the first time in three years, I soon learn that a few pieces of the puzzle still need to be placed before regular field operations can return.

There are several different types of barriers to conducting work in the field. Weather, environment, safety, staffing, supervision, emergency response, planning, equipment, and team expertise all play a role in a successful operation – some of these are out of our control, others accounted for and mitigated through risk assessments and contingency resources. In a perfect storm, the National Park of American Samoa has been hit by a steady flow of setbacks and delays with returning to “normal” work post-pandemic, taking a toll on team morale at times. Right on cue, my first week at the park coincided with some of the biggest waves of the year, a slew of meetings, and a new spurt of volcanic activity centered around the neighboring Manu’a islands – taking dive operations mostly off the table, but giving us extra time to tidy up the back end of the pre-fieldwork to-do list.

Downtime in the office gave me the opportunity to explore the National Park of American Samoa’s impressive visitor’s center

The team focused on safety training and skill refreshers for the first week and a half. Diving on closed circuit rebreathers, Eric and Ian went through several underwater drills and rescue scenarios. At the same time, I buddied on open circuit, familiarizing myself with their gear and rescue procedures while getting used to slinging a 40 L tank of 100% oxygen, which I will breathe during safety stops during repetitive dives in the coming weeks. On the monitoring side, we took several shore dives and snorkels to practice fish identification and sizing, a familiar task to me, albeit in a new ecosystem with plenty of new eye-catching fish to learn.

Marine Ecologist Eric Brown and Marine Biological Science Technician Ian Moffitt rehearsing drills for the rescue of a submerged closed circuit rebreather diver

Practicing fish ID on a shallow shore dive

A significant (and crucial) caveat in our ability to conduct fieldwork is the ongoing updating and streamlining of marine emergency response within the park. With a lack of coast guard vessels in the water and the usual Fagasa Bay boat ramp broken (the area from which we will conduct fieldwork) – the NPS team is working to train an in-house Search and Rescue crew, while simultaneously finalizing the logistics of mooring a second safety boat in Fagasa Bay, in order to minimize response time in the event of an emergency.

My role in these efforts was two-fold. We dove to inspect the existing mooring within Fagasa Bay, which was designated to support two small research vessels until a second mooring could be installed in the upcoming months. I also participated in several large-scale search and rescue drills, focused on initiating and responding to marine emergencies – such as boat malfunction and loss of communication. With the entirety of the park’s marine crew onboard, mimicking a typical field day, several of the NPSA terrestrial and maintenance employees took lead on the emergency response and used these drills to refresh their knowledge of emergency communication workflows and boat operating (from trailering and boat launching to kayaking to moored vessels, navigation, man overboard, and towing drills). By the end of the week, the team was operating like a well-oiled machine and drastically improved response time with increasing familiarity and confidence in each situation.

Marine Ecologist Eric Brown and Marine Biological Science Technician Ian Moffitt inspecting the mooring we will use to store two small research vessels while conducting field work over the next couple weeks

In an emergency, the terrestrial/maintenance response team would drive from the office to Fagasa Bay and kayak out of the moored safety vessel, as seen in this drill.

Finally, it came time for the moment we’d been waiting for. Our first survey dive! The cards had finally aligned (not without the hard work of many divisions within the NPSA team, and substantial frenzy of effort by Eric, Ian, and Tine before my arrival). We had made the two-hour journey by boat from the main harbor, Pago Pago, west, around the island to Fagasa, with both research vessels now in position. We were finally set up for the next week and a half of fieldwork. On the boat and underwater, spirits were high. In the wise words of Eric Brown, we were determined to “keep this train wreck moving.”

My uniform underwater. A 40L 100% oxygen tank used during safety stops and an underwater camera for benthic survey images

On the island of Tutuila, in front of the town of Leone, stands Niuavēvē Rock, a centerpiece and beacon of hope for community members and long-time residents. On this islet stands a single aging coconut tree, enduring natural disaster, generation after generation – against all odds. To thrive in such an environment takes strong roots, resilience, and unwavering strength, qualities mirrored by the people of American Samoa.

Niuavēvē Rock. A single palm on a rocky islet represents resilience and strength to the community, surviving over generations against all odds

These islands may not come with the easy conveniences of life on the mainland. Simple tasks may take longer, the comforts of home farther away, and a dose of uncertainty goes hand-in-hand with long-term planning. But all of this comes with the great privilege of knowing and exploring the natural and cultural beauty that encompasses American Samoa, a place where less than 20,000 visitors set foot each year.

The view from Coconut Point, my new home for the second week of my visit

Exploring secluded beaches on weekends with new friends

Thank you to Eric Brown and Claire for hosting me, helping me get settled in, showing me local eateries, and taking me to explore the island by foot during my first week at the park. Thank you to Ian Moffitt, Norelle Moffit, and Taylor Kamansky for adopting me into the Coconut Point family and showing me the pristine beaches and reefs during my first week. I feel incredibly grateful to be welcomed here and visit a region of the globe I would have previously deemed largely inaccessible to me, made possible with the support of the NPS Submerged Resources Center and OWUSS.