The USS Arizona Memorial from Ford Island

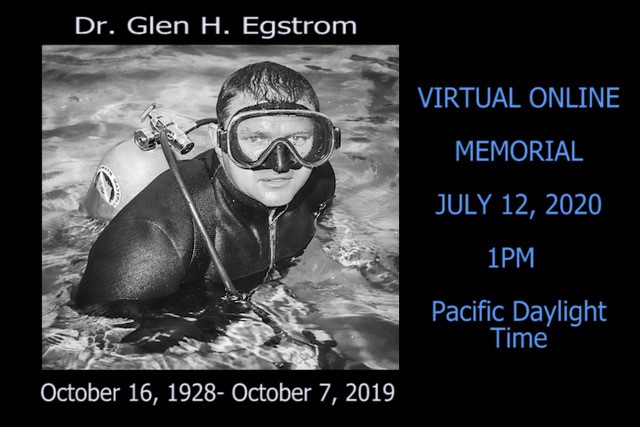

December 7th, 1941, marks the most devastating attack on American soil in history. Early that fateful Sunday morning a surprise attack by Japanese fighter planes struck the Pearl Harbor Naval Base near Honolulu, Hawaii, and inflicted catastrophic damage. In under two hours, these fighters managed to destroy or damage almost 20 American naval vessels, over 300 airplanes, destroy airfields and support structures, killed over 2400 citizens and wounded around 1000 more. Out of all the casualties, almost half of them were from the USS Arizona, a battleship that was struck by an 1800-pound bomb. Detonating in its powder magazine and bringing down the ship with over 1000 crewmen inside, this vessel is one of the only two who still remain in their final resting places. Nearly 78 years later, as my small propeller passenger plane circled over the harbor waiting for clearance to land, I looked down on the hull of the Arizona, silhouette barely visible under the brown harbor water, and wondered what I’d see down there. I had heard stories from others who’d dove the wreck in the past, but still couldn’t really prepare myself for what was to come.

The USS Arizona Memorial from the sky

I was only visiting Pearl Harbor National Memorial for a few days, the first to do some diving and the next two for some other projects. On the morning of September 11th, Dan Brown, Park Diving Officer, picked me up from my AirBnb and took me on base. Pearl Harbor is a massive military base, which was pretty flabbergasting to me. I hadn’t really realized they came this big, and was amazed to see all of the housing, speciality stores, and amenities that were hidden inside. Dan took me to the Parks dive locker, where I met Scott Pawlowski, Curator and diver for the Park. After some quick introductions, we gathered all of our gear and drove out to Ford Island to get to work installing new buoys on the USS Utah. The Utah is the second of the two vessels that remains sunken in the harbor, after recovery efforts on it failed. This ship, a retired battleship that had been converted to a target ship, was struck by torpedoes on December 7th and capsized, taking around 58 crewmembers with it. Recently, one of its marker buoys had drifted off, creating a submerged hazard that nearby boaters could collide with. I was to accompany Dan and Scott as they replaced the existing buoy and added a new one, while photographically documenting the swaps so they could use the photos to train new employees.

The USS Utah, with the memorial in the background

We arrived at the Utah right after a 9/11 memorial was wrapping up. As the final staff members picked up the last chairs and tables, we dragged our dive gear across the grass and started gearing up. Now, the significance of diving in Pearl Harbor on 9/11 wasn’t lost on me – visiting the site of the most deadly attack on US soil 18 years after the second most deadly attack certainly made things a little more intense. I also had no real idea what to expect. I’ve dove on a couple wrecks before, including ones with a loss of life, but none this substantial and with such a historic impact on my country. I was expecting a quiet, low-vis wreck dive didn’t know what it would be like doing that on these historic sites.

Swim-through on the USS Utah

Unlike the Arizona, the Utah is not nearly as much of a tourist site. It doesn’t have a huge memorial built over the wreck or get visited by thousands of people a day, instead sits on the other side of Ford Island near a quiet field in front of a memorial pier, making for a softer and more reflective experience. We took advantage of this more secluded nature and jumped on a visitor-less window to suit up and swim out towards the wreck. Just breaching the surface in front of the pier, rusted shards of the hull and the side of the deck jut out to the water make this wreck seem dynamic and even more aged than it is. We drop into the water and I follow Dan and Scott to the stern. The ship is now laying on her side, making for a disorienting dive as you swim along it, especially in low-visibility conditions. Eager for photos, I made a couple quick stops to capture something before realizing that I was quickly losing sight of my buddies in the murk. It took a lot of self-restraint and careful, watchful navigation to not get lost here. After a little bit of swimming, we arrived on the stern, the anchoring site of the recently escaped buoy. Here, I got into position and snapped away as Scott masterfully tied in a new buoy. After a couple minutes and a lot of shutter actuations later, I found myself swimming back along the heavily listed deck towards the bow.

Scott securing the buoy to the wreck

On the return, navigation was a little easier as it was now my second time making the trip, but I still noticed things I hadn’t seen before (and still had to utilize the entirety of my self-restraint to not fall behind taking photos). I passed stairs plunging below deck, swam past windlasses and marveled as giant 15-foot guns materialized into view before me. This was a bit ship, and the murky waters just added to the mystique of the experience. New, mysterious things would appear in-front of you as you swam along, giving you seconds to take in and process them before the next round of surprises would appear. Before I knew it we were back at the bow where we had started, and Scott and Dan went right to work switching out the last buoy.

Dan replacing the remaining buoy on the USS Utah

Our dive on the Utah was a quick one, as Scott was flying later and had to be out of the water in time for a sufficient surface interval. This fast-paced timeline, along with the fact that I had work to do and didn’t want to disappoint, meant that I didn’t really think much of the history of the ship while I was diving on it. For the Utah that realization came later while I was standing on the memorial pier after changing out of my dive gear. Looking at the rusted remains that rise out of the water and the bronze plaque commemorating the fallen, I thought about what it might have been like to go down with that ship, to be trapped below deck when it capsized that dreadful Sunday morning. A frightening thought, and something that I knew would be on my mind later when I’d be diving the Arizona.

One of the guns on the USS Utah

After a quick lunch with Dan, we set off to our prep point for the Arizona dive. This would be different for a few reasons. The Arizona gets many more visitors than the Utah, with more than 1300 a day visiting the memorial, so we had to try our best to not be distracting (which is tough, as SCUBA divers are incredibly interesting to many people). We had a different task – this time I was to photograph marine life on the wreck, for the NPS to use in creation of outreach materials – so I had to put my head in a different place and prepare myself mentally for a new job. It’s a larger vessel, about 100 feet longer than the Utah at 608′ total length, meaning we had to be more attentive to navigation. Finally, we had a time constraint – the Navy had some sonar tests planned at a nearby dock, so we had to be out of the water before those started.

The bow of the Arizona in murky harbor water

With all of this information swimming around our heads, Dan and I swam out to the marker buoy on the bow as stealthily as possible and dropped in. Visibility was slightly better here, shifting between 5-12 feet, so I quickly got to work and started snapping away at anything alive. Photos of biological life are my favorite types of photos to take but I knew I still had to work hard to capture compelling images of it in low visibility, especially when most of the life is encrusting invertebrates. The hull of the ship is completely covered in life of all kinds, as hard structure in a silty harbor environment attracts many different species. Sponges, tunicates, bryozoans and corals adorned the deck and structures and turned them into a multicolored array of life. These organisms, while intricate and beautiful, are a bit hard to glorify with a wide-angle lens (which I had equipped), so I focused on juxtaposing them with the wreck itself for greater impact.

While swimming along the deck of the Arizona, it really became clear just how large this ship is. Resting face-up in a sea of mud, diving this sites wasn’t nearly as disorienting as the Utah, and travelling along it allowed for a full comprehension of exactly what you were on. Seeing some of the large, intact structures that remain on the ship, like the huge barrels of the 14-inch gun turrets, was a stark reminder of what you were on – a battleship.

-

-

The 14-inch guns

-

-

One of the gun barrels, with Dan for scale

As I was photographing life on the wreck, I also took some time to capture snapshots of little reminders of what occurred here. Unlike the Utah, the Arizona still has a lot of artifacts from the crew who used to live there. Its ‘gentle’ descent to the harbor bottom likely assisted in this, so some items still lay on its silent decks. During our dive we passed things like a pitcher in what used to be the galley, or the remains of an unlucky crew member’s boot.These served as a solemn reminder of the tragedy that occurred here years ago, and that the past occupants of these silty decks, despite the years in between and occupational differences, were just as human as I am.

-

-

The remains of a boot

-

-

A pitcher

Interspersed with moments of reflection and focused shooting, I was hit with tinges of panic relating to a very pertinent issue for me in that moment – I was working with critically low camera battery. After our Utah dive, I had forgotten to turn my camera off, which normally is a non-issue as it automatically goes into a battery-saving sleep-like mode. However, a recently developing sticky shutter problem that I was battling caused the camera to stay active the entire surface interval, draining my precious battery-life and threatening to cripple my ability to work. This, unfortunately, was not an issue I noticed until I had descended into my dive, starting off with a pitiful 24% battery. I was now stricken with a difficult dilemma – trying to conserve my battery long enough for it to last the entire dive, while also wanting to photograph everything I saw on this once-in-a-lifetime dive. This was especially stressful as I again wanted to deliver on my task to produce good images of the life on the wrecks, and shooting incredibly conservatively to sustain a dying battery isn’t always the best way to do that. Thankfully, fate worked out in my favor and I managed to stretch the battery to last the whole dive (with a whole 4% to spare at the end too).

Stairs going below deck on the USS Arizona

When we reached the stern of the ship, we visited two locations that were especially somber to me. The first one was seemingly innocent – the empty turret where some of the rear guns used to lie – but has a different use today. As we dropped down into this cylinder, somewhat reminiscent of a large smoke-stack, we were met with a large deposit of fine silt with a rope descending into it. This, as Dan signed to me, was where survivors of the bombing can choose to be laid to rest. Out of the 1512 crew members on board, around 300 of them survived the attack. If they desired, their cremated remains would join those of their crewmates in the Arizona itself, and the way in was through that silt. The remains would be lowered below deck through a hole in the base of the turret in an elaborate ceremony. Being in such close proximity to a way into this ship, which effectively is a tomb for the 1000+ people who went down with it, as well as thinking of what it must have been like for the survivors, who lost so many of their friends and chose to be buried with them, made this a very meaningful moment. The other location was the portholes on the side of the ship. Unlike the silt in the remains of the turret, these portholes were literal windows into the ship, glimpses into the dark insides of a deep tragedy. It was odd looking in these and thinking that no one has been inside these rooms in almost 80 years, and that the last time they were occupied something absolutely terrible happened. Furthermore, there was an ebb and flow of water coming in and out of these portholes. Out of place in an otherwise calm harbor, this must have been caused by slight currents moving through the hull of the ship, travelling the maze of passages inside. To me, this dynamic movement made the Arizona seem alive in a way I hadn’t seen before. I thought about what the current had passed by on its journey through the ship, how it had brushed past things that hadn’t seen the light of day in decades.This flux of water in and out of the ship seemed to compliment the sentiment around the memorial. Despite being entombed in the vessel indefinitely, the memory of these lost sailors was still very much intertwined with the outside world, with sentiments constantly coming and going with the tides.

A porthole on the USS Arizona

Coming up from the dive, I had a lot on my mind. Along with lots of questions for Dan that I just couldn’t figure out how to communicate to him underwater, I had also just dove on what is essentially a mass grave. I’m not naturally a somber person, but it came pretty easily here. Looking past the loss of life, its also a pretty cool dive, so I was a bit excited. Diving on a battleship itself is a rare opportunity, but diving the one whose sinking essentially kickstarted the US’s participation in WWII – a pretty incredible chance to explore a historic site in a way that only a really select few are able to. Still buzzing from that dive, I headed home that night eager to look through my photos and to log my dives. I had a lot to write down.

The rope on which remains of the Arizona survivors are lowered into the ship

The next day I met Dan at the visitor center and started to look through my photos with him. We wanted to select a few shots of life on the wrecks, identify the life, and then to create some informational material for visitors. I had edited and picked some selects the night before, but the identification proved to be a more difficult task than initially thought. Almost all of the selects I had chosen were of invertebrate life, as the few fish I had seen on my dives hadn’t been agreeable subjects. Invertebrates, to those from a non-biological background, can be a bit difficult to identify sometimes. While family and genus are sometimes easy, locking down the exact species can often be pretty tough, sometimes requiring time-intensive keying out or even a microscope to pick out defining features. To make this even more difficult for us, we didn’t have an ID book on hand and had to resort to internet guides. Thankfully, quite a few of the species were common ones, and we had the assistance of local experts like Eric Brown via email, so we were able to lock down a couple IDs for the outreach project. After this, I helped Dan with a few errands around the base. This was a cool opportunity to see more of it, still very exciting for me as I’d never spent much time on any base before, let alone one this size. It was thrilling to drive along and see huge battleships moored beside the road, and Dan did an excellent job showing me some of the historic sites the base had to offer.

The USS Bowfin

On my final day at PEARL, I did some sightseeing. Scott was nice enough to hook me up with a Pearl Harbor Memorial Sites Passport, which includes admission to the Arizona memorial as well as three of the other historic sites on base : the USS Bowfin, the USS Missouri, and the Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum. This was a long day of tourism, but was a highly educational experience. It was nice to learn more about the war and the event that started it for the US, certainly put the last couple days in a bit of context. I thought the Memorial and it’s associated museums did an excellent job portraying the attack from both sides – the US and the Japanese. They included eyewitness testimonies from veterans from both countries, highlighting above all that this was a human war, hurting people from each land, not just a faceless enemy murdering for pleasure. I also found touring the USS Missouri very interesting. The battleship where the treaty ending the war was signed, the Missouri is open for visitors to go inside and explore its halls and rooms. This put the Arizona in a new light for me, as it revealed just how huge that ship really is. It’s hard to comprehend while swimming along the deck how much of the ship is closed off and hidden away, buried under mud and impossible to see, but walking the never-ending halls of the Missouri opened my eyes to the immense area below deck where most of the life on these ships really took place.

The USS Missouri

Visiting the Pearl Harbor Memorial was a very impactful experience for me. Diving on and seeing these historic sites in person is powerful and hard to describe. The memorial does an excellent job of honoring those who passed. Despite having passed decades ago, these lost crew members still influenced the hundreds of visitors who view the memorial every hour, people who come to learn and pay their respects. Their sacrifice, whether or not it was in defense of a mutual belief between the crew and the tourists who come, was a human sacrifice. They lost their lives defending something that was dear to them – their country, their freedom, their families. It doesn’t matter whether or not people viewing the memorial agree with US foreign policies or even agree with the US’s position in the war. Everyone can emphasize with giving your life to protect what you stand for.

The names of the fallen in the Pearl Harbor Memorial

Leaving Pearl Harbor was significant to me for one more reason – it marked the last park in my summer of adventure. After a short week off, I would be flying off to DC for some final presentations, before ending this wild internship. While sad its all coming to an end, I think PEARL was a fitting end to this journey. Starting off, I learned how the NPS works to preserve submerged archaeological treasures, then how they monitor and protect biological resources. Travelling to Kalaupapa, I saw how they protected historic sites to ensure sensitive past transgressions aren’t quietly swept under the rug, and at Pearl Harbor I saw how they preserved and honored the memory of those who gave their lives for our country. Feeling as though I had experienced a diverse array of the places and resources that the National Parks Service works to preserve, I now felt ready to go to DC and share what I’d experienced.

The USS Arizona Memorial