The morning of July 11th, I met up with Mike Feeley and Jeff Mills in Miami. With the 26-foot Twin Vee Catamaran in tow, we began making our way down to Key West. The drive down Overseas Highway is one of my favourite drives – 120 miles of palm trees and clear blue water out both windows. In fact, I just made this drive at the end of May with my undergraduate research lab. Every summer, Dr. Malcolm Hill’s lab at the University of Richmond travels down to Summerland Key to spend a week or two doing fieldwork with marine sponges. So I’ve made this drive for the past three summers and it’s come to be quite familiar.

SFCN crew: (front) Mike Feeley, me, Rob Waara, Nicole Palma, Erin Nassif, Lee Richter, Jeff Miller

MV Fort Jeff crew: (back) Brian, Mikey

Mike and Jeff are two of the biologists working for the South Florida/Caribbean Network (SFCN) and this week I was joining their crew. SFCN is one of 32 NPS Inventory and Monitoring Networks across the country. These I&M Networks are in charge of collecting and analyzing natural resource data for parks and then providing them with information that can be integrated into park planning and management strategies. Specifically, on this trip to Dry Tortugas National Park (DRTO), we would be performing annual benthic surveys on sites that the SFCN has been monitoring for years.

I was surprised when we pulled up to the Naval Air Station in Key West, but this was where we were meeting the Motor Vessel Fort Jefferson. The MV Fort Jeff is a supply vessel for DRTO owned and operated by the National Park Service that would serve both as our transportation to and from the park, in addition to our housing for the next 10 days. When we pulled up to the bulkhead where the MV Fort Jeff was docked, my eyes widened with excitement. I’ve never even seen a full-scale research vessel before (aside from on TV specials on the Discovery channel) and I was so eager to be spending my week on board.

Shortly after we arrived, Rob Waara and Lee Richter, the other half of the SFCN staff, and interns Erin Nassif and Nicole Palma pulled up to the dock with a truck packed to the brim with supplies for the week. On their way down, they had gone grocery shopping to get food for the eight-person team for our 10-day voyage, a very important task. We spent the afternoon unloading the trucks, launching the Twin Vee, and double-checking we had everything we would need for the expedition before settling into our quarters.

The next morning, it was all hands on deck as we helped Captain Tim, Brian, and Mikey push off out of Key West at 0700. Located about 70 miles west of Key West, the Dry Tortugas can only be reached by boat or seaplane. Ever since their discovery by Ponce de Leon in the early 16th century, the Dry Tortugas have had an incredibly rich history. The location at the mouth of the Gulf of Mexico made them an incredibly important stop along shipping routes heading into or out of the Gulf. As such, a fort was commissioned to be built in the early 1800’s by the United States. During the Civil War it remained in Union hands as a naval base and later was used as a prison. Though it was never technically completed, the Fort Jefferson stands as the largest masonry structure in the Americas, with 16 million bricks making up the imposing three-story, hexagonal fortress. Today, its casemates house National Park Service staff and thousands ofvisitors flock to the park to walk the parade grounds of this historic structure.

After about 4 hours of cruising the open water, the Civil War fort appeared on the horizon. As we approached Garden Key and the bricks began to take on shape, I was taken aback. The fort, surrounded by a moat (which I discovered later had a crocodile living in it), looked like something out of a medieval fairytale. This and the 100-square miles of ocean surrounding the fort would be our stomping ground for the next 10 days.

That evening, we went over the game plan for the week. SFCN has been monitoring three sites at DRTO – Bird Key, Loggerhead Key, and Santa’s Village. Each site is comprised of multiple permanent 10-meter transects that are surveyed to monitor coral species, colony counts, and cases of disease. As the only things marking the permanent transects are metal pins fixed to the reef, the dive operations would be divided into two teams. The navigation team would dive first in order to locate the pins using compass bearings and distances and lay down the 10-meter transect tape between the two pins. The survey team would then drop, perform the survey, and collect the tapes.

The next day we loaded the Twin Vee with all our dive gear, a water jug, and a lunch cooler and set out on our first day of surveys. As my coral identification is not as practiced as that of Mike and Jeff (who have been doing this for years now), I joined the navigation team. Equipped with a compass, transect tapes, and a slate with pictures of the site, Lee, Nicole and I splashed in to lay down the transects for the survey team. What I thought would be an easy task, turned out to be an exciting challenge. Distances and bearings were not always enough to find the pins. Oftentimes they were covered with algae, hidden at the base of a sea fan, or overgrown by a sponge. Most of the time we relied on the pictures of the site to locate the pins, sort of like an underwater game of “I spy…”. When we came up for our surface interval, the survey team would go down to work on the transects we set out. We repeated this process again before it was time to head back in to the MV Fort Jeff for dinner.

Even though I was on the navigation team, it was hard not to stare in awe as DRTO reefs were teeming with life. I’ve been told that the reefs here were what the reefs of the Keys used to look like decades ago. Large groupers and snappers, which have been fished off the reefs in the Keys, thrive in the park’s remote and protected waters. Large boulder brain corals and great star corals populate the reef’s hard bottom with soft corals and gorgonians swaying in the current. Despite this, algal growth and coral disease, often indicators of unhealthy or declining reefs, were also very prevalent.

It wasn’t long before we fell into a comfortable and efficient rhythm. We spent every day on the water. We picked up wherever we left off the day before and would motor over to the next site when we wrapped up the one we were working on. Four transects per dive with two dives a day allowed us to wrap up each site in two or three days, depending on the weather. After returning from the field, Nicole, Erin, and I would spend the evenings exploring the fort or snorkeling along its perimeter.

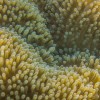

- Sun Anemone (Stichodactyla helianthus)

- Green Tentacle Zoanthids

- Unknown Blenny

- Bait fish

On the second-to-last evening, I had the opportunity to join the United States Geological Survey (USGS) crew on their nightly East Key turtle nesting monitoring. We motored the short distance over to the 100 by 200 meter island where we would be spending the night and set up camp before it got dark. Every half hour someone walked the shoreline to look for a nesting female. Luckily enough on the 2200 walk three turtles had come up to nest. I had never seen a turtle nesting before. It was miraculous to watch these 300-pound beasts lug themselves up on shore and sometimes go hundreds of feet before finding the perfect spot to dig their nest. Some even dig multiple holes until they find the right one to lay their clutch in. The whole nesting process took an hour or two to from start to finish.

We monitored each turtle’s nesting progress and once they had finished, before they returned to the ocean, we corralled them on the beach in order to gather data on them. We noted the species, took various measurements on size, collected a blood sample, and tagged any turtle that hadn’t already been worked up this year. We had two returners. Esther was a Loggerhead who had nested and been worked up earlier that year and Maria was a Green who has nested in past years but hadn’t been seen in awhile. The third turtle was a new Loggerhead who I named Sydney. After finishing up with Sydney around 0100, the rest of the night was uneventful and I got some sleep under the light of the stars. We returned to the fort just in time to watch the sun rise.

On our last night in the Dry Tortugas, the rangers called together a potluck. Everyone gathered in the crew quarters at the Fort as we laughed and shared stories of the week around delicious food. We talked well into the evening and even got to witness a green flash as the sun set over the cloudless horizon.

In the end, my time in DRTO was more than I could’ve imagined. The SFCN crew was friendly and warm and I was delighted to have lived and worked with such a passionate team of NPS staff. I’d really like to thank the entire SFCN team as well as the MV Fort Jeff crew for putting up with me during those 10 days and allowing me to join in on your annual monitoring effort. It was an incredible learning experience!

“Always remember kids. Today is a great day for a day!” – Mikey Kent

Next stop…Wisconsin?