Having spent the last several years away from North America, I often worry about losing my “Canadian blood.” Is the antifreeze that naturally runs through my veins wearing thin? I have not spent an entire winter in the great white North since 2016 (my second year of undergrad), and I have been quite successful in avoiding the 7-8 months of snow and 1-2 months of -40C that my hometown is gifted with each year. But by now, I am due for another round of cold weather adventures – and I am tremendously excited to dive into the crisp, clear blue of Crater Lake.

Crater Lake National Park. Photo: Nate Akers

I land in Medford, Oregon, greeted by the airport shuttle bus driver who will take me to the off-site rental car office. Over small talk, he tells me that summer has passed (as of three days ago). He speaks to the steep, sudden decline in temperature (from 90 degrees and sunny last week to 60 degrees and rainy the next). But really, his outfit screams the same nonverbal story. Shorts, flip flops, and a breezy T-shirt… in 50-degree overcast skies. I recognize this familiar homage and resistance towards acknowledging that another short-but-sweet summer has passed. Just a few more days of shorts… before the layers come out and a long winter ensues. He jokes that my arrival has triggered a cold spell that will last throughout the week. That was music to my ears. It sure feels good to feel like home.

Sunset from the scenic Rim Drive during my first evening at the park

A historic stone cabin, towering ponderosa pines, and a lively group of seasonal NPS employees set the stage for my stay at the park. I am immediately impressed by the amount and diversity of natural resource management work happening within the park, from trails, to backcountry, streams, botany, and lakes – I am given a small glimpse into each of these programs throughout my stay.

Our goals for the week are varied but begin with site assessments of one of the lake’s most mysterious underwater landmarks – referred to as the Fumaroles. Cut deep and cylindrical into thousands of years of accumulated peat; they are long-standing natural formations and tunneling depressions in the benthos, of unknown origin and mechanism. What causes these formations? How have they maintained their form over thousands of years? Surely these exist elsewhere, but where? With the hope of garnering insight and scientific advice from other regions around the globe, the NPS Submerged Resources Center will visit Crater Lake next year to document and model in unmatched detail the anatomy of these strange formations, using cutting-edge, in-house-developed, 3D photogrammetry technology.

The “Fumaroles.” Crystal clear waters and mysterious formations amidst ancient peat.

Not long into our first dive, I am met, face to face, with Crater Lake’s most wanted aquatic criminal – a member of the introduced crayfish population. Diving alongside NPS Aquatic Ecologist Scott Girdner, former NPS Aquatic Ecologist Mark Buktenica (and continued NPS volunteer diver), and Fisheries Biologist Joshua Sprague, we conduct benthic aquatic invertebrate surveys as part of an annual monitoring program to quantify the impact of invasive crayfish on the declining endemic newt population. In particular, these surveys aim to evaluate how food availability is altered in areas that crayfish occupy – and park ecologists have indeed detected a dramatic reduction over time. Previous mesocosm studies conducted within the park also identified changes in the behavior of endemic newts in the presence of crayfish (such as the inability to coexist and being driven out of rocky sheltered habitats and induced stress response – driving newts to the surface to gulp air where they are preyed upon by introduced invasive fish).

An invasive crayfish, introduced into Crater Lake over 50 years ago, and threat to endemic newt populations

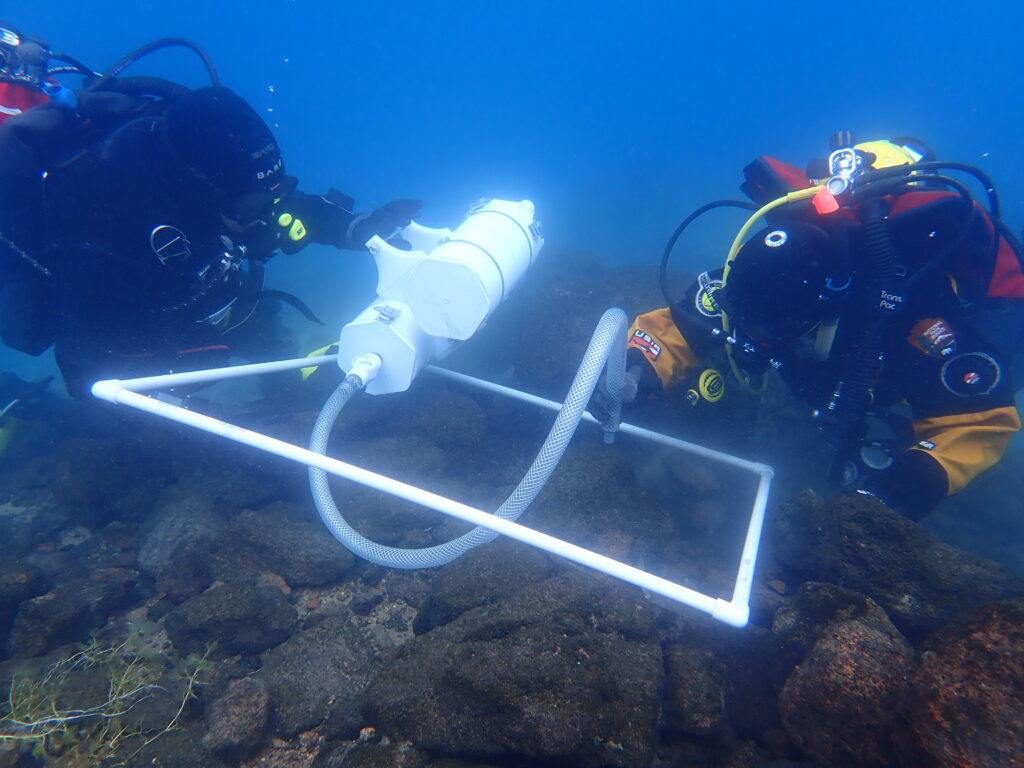

Aquatic Ecologist Mark Buktenica and Fisheries Biologist Joshua Sprague using an underwater vacuum to collect benthic invertebrates within a 1 meter transect

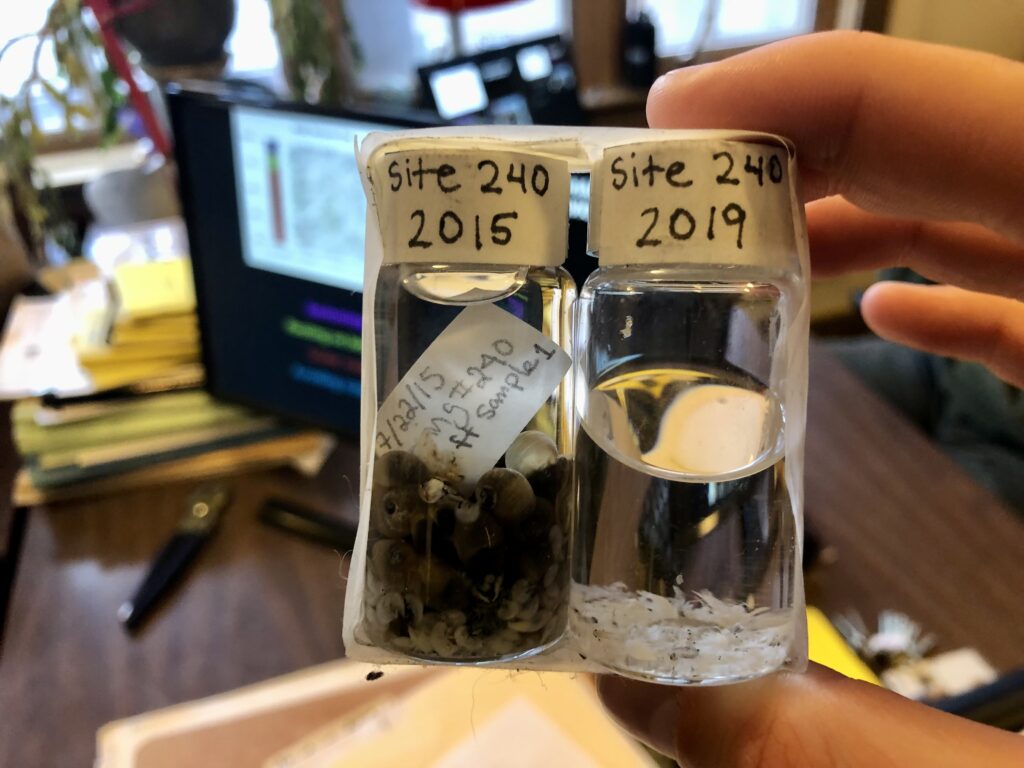

A compelling example of the reduction of food availability in areas before (left) and after (right) the introduction of invasive crayfish, based on benthic sampling

A topic of interest to me, and the theme of my Master’s thesis work, invasive species are ubiquitous in the present day. Within Crater Lake, Rainbow Trout, Kokanee Salmon, and crayfish have been introduced for tourism purposes – to provide recreational fishing opportunities for visitors. However, over 50 years later, we are beginning to see the repercussions of these actions, and the endemic newt population of Crater Lake is in peril. Once past a certain threshold, an invasive species is almost impossible to eradicate. It is likely a question of when, not if, the newt population will be extinct within the park, with unknown consequences regarding ecosystem health and function. Nowadays, many teams within the Crater Lake natural resource staff work to prevent other invasive species from becoming established – hoping to keep these areas pristine, natural, and native.

Every effort is made to prevent further introduction of new invasive species (including a complete ban on recreational swimming accessories – from goggles to paddle boards), in order to preserve native plants and aquatic organisms

Scott Girdner and Mark Buktenica lead the way for us aquatic interns and seasonal employees, with a combined total of 64 years of experience in and on Crater Lake. Highly attuned to changes in this unique environment, this impressive body of knowledge has been generated year after year, dive after dive, since the 1950s. A testament to the success of the NPS dive program on the ability to cultivate detailed knowledge of natural resources within the park to inform their protection and preservation. This is one of the only parks I visited this summer with such long-term knowledge contained within a single, or couple, of individuals. Knowledge, however, that is free for the asking, as Mark and Scott generously provide mini lectures on the boat before embarking on each new task, contributing to a short but highly successful and educational visit.

Topside view of dive operations

Aquatic Ecologist Scott Girdner and I conducting a shore transect to monitor the growth of filamentous algae booms, a recent occurrence in Crater Lake under changing environmental conditions

Over the week, not only does the dive team work as surveyors of natural resources (from “bug sucking” to crater exploring), but also underwater mooring repairmen, off-road tractor drivers, construction (and deconstruction) workers, weather station mechanics, backcountry hikers, and boat operators. Entering the workforce as a young professional, I aspire to cultivate such a well-rounded skill set, and the ability to contribute to each aspect of these field days, perhaps one day leading a team of interns, students, and employees with a built wealth of knowledge.

NPS Aquatic Ecologist Scott Girdner and Mark Buktenica installing a new solar panel on the weather monitoring station

Overlooking Wizard Island, volcanic cone and crater

Beyond the mesmerizing mystery that is the cold depths of Crater Lake, my time at this park stands out for the community of seasonal employees I met at Sleepy Hollows. Thank you, all, for welcoming me into the park, sharing your perspective, friendship, and personal journeys with me. A special mention to Nate Akers for introducing me to the crew during bonfires, games nights, and Christmas-in-September celebrations, and Hamilton Hasty for showing me hidden gems within the park. Thank you to Scott, Mark, and Josh, for hosting me, answering my many questions, and letting me in on one of perhaps the best-kept secrets of the National Park Service Dive Program. It is not only the rarity of this experience that lingers with me, but the evolving desire to continue cold water diving in even more remote and even colder parts of the globe.

Countless hikes line the rim of Crater Lake

As my internship nears completion, the significance of this opportunity, in terms of personal and professional development and the support I have received from those around me, is at the forefront of my mind. My advice? If given an opportunity so rare, so unique, and so beautifully mysterious as to dive and work in places not even your highly skilled, well-traveled, and internationally acclaimed supervisors have (those same folks who are cracking open doors for you to get into these excellent parks, with the support of the entire NPS diving program)… Run, don’t walk! Send in an application to OWUSS and NPS, share your story and your curiosities, and see how far it takes you. Whomever the next National Park Service Dive Program intern may be, I look forward to welcoming you into the NPS and OWUSS network with open arms, just as those before have done for me.

Such amazing photos!