I can’t see anything. I’m just pushing brush away from my face and blindly taking the next step, hoping it’s not a deep hole. “The trail sure got grown over from last year!” I hear Eric Brown, Marine Ecologist at Kalaupapa National Historic Park (KALA), shout over his shoulder. We are hiking deep into the backcountry of the Waikolu Valley. At the valley’s floor lies Waikolu Stream, the natural feature that brings us here.

Waikolu Valley from the water.

Further up the trail, the brush gives way to infinite guava trees. I can see at least 25 guava trees at any given time without turning my head. As I pull a ripe one off a tree, Anne Farahi mentions, “make sure you don’t have any cuts on parts of your body that will be going in the water. That’s how you get lepto. Senifa (previous biotech at KALA) got it last year and it was not a fun experience for him.” Good to know. I crunch into my guava and keep walking to checkpoint- the mango tree.

Anne Farahi crosses a stream in the Waikolu backcountry.

“The mango tree” is the largest I’ve ever seen. It is close to our first survey site of the day. At the mango tree, we check our GPS and make our way down to the stream. Our surveys at the stream are similar to the surveys I was doing last week with Eric in the ocean in that they are both long-term monitoring projects. Eric has been monitoring this stream for many years. We are conducting fish and snail surveys, measuring water quality (in the same way that we did in the ocean), collecting data on bottom composition/boulder size, and tracking stream flow. Since Eric and the KALA team already have past data from the stream, they can quickly see if something is out of the norm and strategize how best to combat any issues that may arise.

The difference between this study and many others is the remoteness of Waikolu Stream. KALA itself is fairly remote already and far out of cellular service. Waikolu is a 30 minute drive and then another 45 minute hike to base camp. The other big difference is that most monitoring projects monitor things that humans use. Waikolu Stream used to be KALA’s main water source, but it hasn’t been for a few decades.

The hike into Waikolu backs up against breathtaking sea cliffs.

I ask Eric about this, why does the KALA team monitor this stream? “We don’t want this stream to change. So many streams have been dammed up in Hawai’i, this one actually was as well at the bottom and Native Ancient Hawai’ians diverted the stream to put water into taro fields. This stream is still in very good condition though, and we want to keep it that way.”

This resonated with me. Eric and I see eye to eye when it comes to keeping wild places wild for the sake of keeping them wild. Very few people take this approach to conservationism, which is really more of a preservationist view. I’m glad Eric (or as his friends call him, “the good Dr. Brown”) is doing it, and I’m glad to be apart of it.

When I say lay in the stream, I mean lay in the stream.

When we get to the first site, Anne is putting on a 5mm farmer john wetsuit. Seems a bit like overkill to me until I see Anne literally lay down in the stream and start counting fish. She is the perfect person to have in the backcountry. She has the most generous heart, quietly has a bit of wanderlust in her, and never complains. Furthermore, she’s been working with the Pacific Parks NPS Inventory and Monitoring team for many, many years. Even salty veterans admit that Anne knows her stuff.

Amanda McCutcheon counts fish during a survey.

While Anne begins counting fish, I work with Eric measuring stream flow. “Always start at the point furthest down stream on your survey line. You don’t want to go upstream and alter the data down stream,” he tells me. This is also why we are starting with the site closest to our basecamp (which is where the stream meets the ocean) first.

Go with the flow! Eric and Laurene use the stream tracker to measure stream flow.

We use a piece of equipment called the stream tracker to measure flow. It can be difficult when the stream gets deep in some spots and really shallow in others. This is because the computer reads the flow as an error when it moves slowly over a deep spot after rushing through a shallow passage. After we get the data and I start to get the hang of things, we take water quality samples just as we did last week in the ocean and move to our next site.

Completing a survey is quite the process and takes about 2 hours at each site with a team of 5 people working. Luckily, we only do two today since it is our first real day in the backcountry after unloading, setting up camp, and doing one survey yesterday.

“Found it!” Eric says as he puts secures the stern anchor behind a big rock. “Toss the line in!” he shouts. I give him the long bow line to swim to shore. He hands it to Anne and Amanda McCutcheon on shore to tie around a giant boulder. “Ok, I’m ready!” Eric tells Laurene and me. We start handing him coolers and dry bags. One at a time, he swims them to shore and unloads them to Anne and Amanda who carry them up the rocks. This is controlled chaos at its finest.

The process of getting gear onto the beach at Waikolu is a tricky one!

Somehow, nothing gets wet and the process takes less than 20 minutes. “I think that’s a new record!” a sopping wet Eric Brown exuberantly proclaims. Laurene hops in the water and swims to shore while Eric and I make the return mission on the boat through the rough backside of the KALA peninsula back to the harbor. Once there, we will drive to the trailhead and hike back into Waikolu Valley to meet the rest of the team, help set up camp, and conduct our first survey.

Once we are back in camp after our first survey day, it’s time to eat. Eric prepares some delicious vegan chili for us, which is a perfect hardy backcountry meal. There’s only one issue. Everyone is having trouble pouring water out of the giant 10 gallon water filter bag. I tell the group, “I think I can make something to help us. Does anyone have some rope or parachute cord?” Luckily Eric has some, and I get to work.

My contribution to our camp- a tripod.

Growing up in the Boy Scouts, working at a Boy Scout camp, and eventually reaching the rank of Eagle Scout, I never thought I would use lashings much. I’ve been surprised how much I’ve used them through the years. Once I find three tall pieces of drift wood, I use diagonal lashings to create a tripod that elevates the water bag and makes it easy to pour. “This is quite the invention! It’s really useful! I definitely had no idea what you were doing over there with some sticks,” Anne says with a laugh. I respond, “that’s my one contribution this trip! Had to get it out of my system early ha ha.”

After a rainy night and early start getting onto the trail, we are already far past where we surveyed yesterday. Today is our most challenging day where we are going deep into the valley. We have been squashing guavas and wading through brush in intermittent drizzle for about an hour and a half. All of a sudden, we see a cute but terrible scene- a den of tiny kittens. These kittens are unbelievably adorable. Tiny little fluff balls.

Kittens! Not a good sign…

“Ohhhh no. Not good. We’ve never seen cats this far back into the valley. This means there is a mother and father as well. We are going to have to kill them,” Eric states, very matter of fact-ly. Eventually Anne and Amanda’s pleading works and Eric doesn’t kill the kittens. Though, I would not be surprised if he went back and did it.

We arrive at the site soon thereafter and complete our first survey. On the way to our next survey, we see remnants of a housing structure. “This is where the workers would stay overnight when they were putting in and working on the water lines,” Eric tells us. “They would clear brush all the way back to here and use Jeeps to drive up as much equipment as they could.” I’m amazed. We are deep into this valley. Installing a pipe and building structures back here must have been so difficult logistically. It was certainly a feat of engineering.

It is truly unbelievable that workers built infrastructure deep into the valley many decades ago. Here is a house they used to sleep in overnight.

At our second site, I work with Amanda counting and measuring snails. Once we are ready, Amanda lays in the stream and sticks her face in the water. Without looking up, she hands me 3 snails. I measure them, record that data, and place the snails in a calm pool of water beside me. We do this until all the snails in our survey area have been counted and measured. Amanda pops up from the water, “30 spat, 60 eggs.” She gives me the count of spat (juvenile snails) and snail eggs.

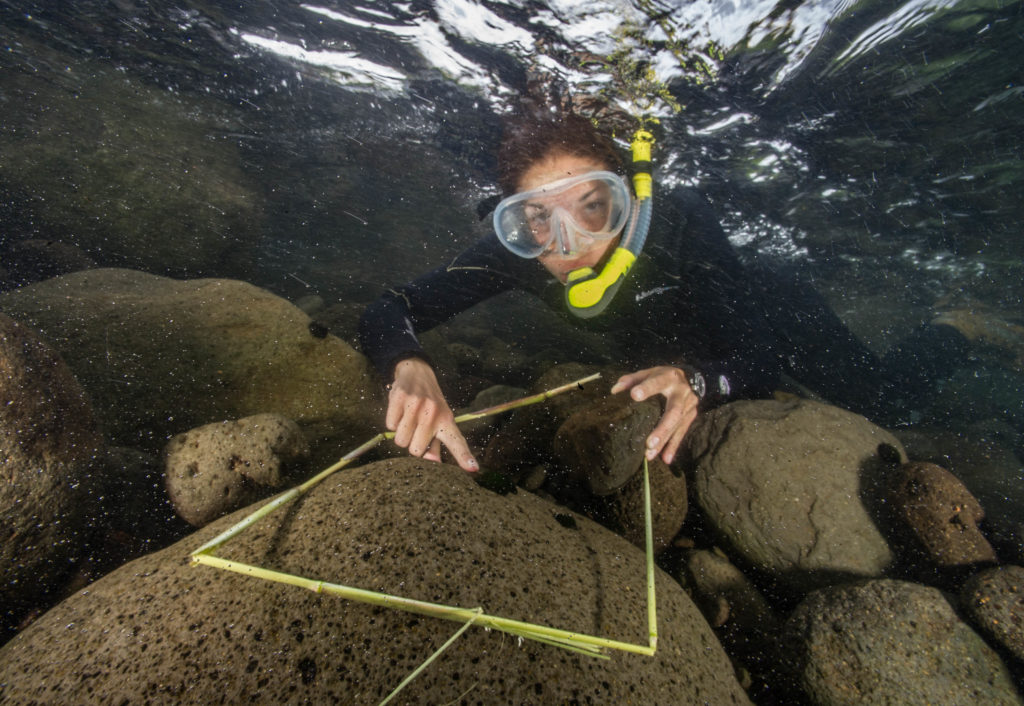

Amanda points to some snails in her survey plot.

Amanda is a seasoned Pacific Island scientist. She completed her graduate school at the University of Guam and has been working with the Pacific Parks NPS Inventory and Monitoring team since. She is based out of Kaloko-Honokohau National Historic Park, my next stop. I appreciate Amanda’s understanding of the importance of communicating science and her efficient, workman-like mindset in the field.

After our second site, we make our way back down to basecamp. We experienced a little bit of wind and rain up in the valley, but apparently it was much windier at camp. 3 of our tents have blown up into the valley, including mine. I head out to grab it through some razor sharp brush. The tent is too heavy to pick up, so I have to empty some items into my backpack and then try to move the tent. This works, and then Eric helps me look for my missing stakes. I’ve done quite a bit of camping and backpacking in my life, but I have never had a tent blow away on me.

My tent wasn’t the only one that blew away. Here, Laurene, Amanda, and Anne work to put another tent back into place.

After the tent fiasco, it’s for me to start cooking dinner. I put some rice on to cook and debate whether I’d like to take a “shower” tonight or not. Usually, I go pretty light on showers in the field. It’s hard for me to justify getting salt/dirt off myself when I know I’m going to throw it right back on in a few hours. However, tonight, I decide to bathe. Before I head over to the stream, I let the crew know, “if you hear someone screaming, it’s me being a wimp in the cold water.” Even though I spend a lot of time in cold water back home, it never really helps me deal with cold water. The stream certainly isn’t freezing, but it’s quite a bit colder than the ocean.

Dinner time at base camp.

However, the real reason I’m bathing tonight is that I want to try a traditional native Hawai’ian shampoo/soap that grows all over the trail. It is a type of ginger with a large red bulb that grows above ground. Squeezing the bulb releases a soap-like substance that the ancient Hawai’ians used as shampoo. Turns out, it works really well. Combined with the cool stream, the bath was energizing and invigorating.

The dinner I’m cooking is a peanut sauce stir fry that has few ingredients and is easy to whip up on a camp stove. It’s still a little challenging to cook for 5 people on a single burner with small pots. Once the food is done, everyone piles on the rice, veggies, tofu, and sauce and we feast. The first person to go for seconds is Laurene (she took one of the smallest portions). “Laurene! Going for more?!” Eric asks. Laurene states, “yes! I’m hungry after all that hiking!” To which Eric responds, “Laurene! The bottomless pit!!” We all crack up and hang out around the dining area for a while before cleaning our dishes.

Some of my first shots were of Laurene’s tent.

Around 9 PM, everyone is starting to think about bed and I’m starting to think about getting my camera out. The stars are out in force tonight. It is a new moon with spotty cloud cover, and the Milky Way is coming out. I decide to take my camera out and get a few shots. Unfortunately, I have no way to take my camera out of its underwater housing. I vacuum sealed the housing and don’t have the equipment with me to release the vacuum. It’s still shoots fine, it just weighs about 25 pounds more.

I’m getting some good shots of the stars and Laurene’s tent, but the tent-night sky shot is overdone. I come back to the crew, now completely ready to go to bed and ask, “anyone want to do a stream crossing?!” I mostly get groans and a chorus of “no thank you,” except for Anne. “Sure! Why not? I’m not doing anything else.”

Anne Farahi during a late night stream crossing.

We head to the stream and I have Anne step into the water and stay still. “Ok! I’m ready, stay steady…headlamp on! Headlamp off!” I get the shot I was hoping for, but some clouds block the Milky Way in the photo. “That was so close to perfect! Let’s do a few more, we need these clouds to cooperate,” I let Anne know. She seems pretty excited as well. We take a dozen more shots (they take 30 seconds each to take, so this isn’t a super fast process) and then try something new.

“Susanna from the SRC (Submerged Resources Center) challenged me to try to get an over/under shot of the Milky Way on top and coral reef on the bottom at the beginning of this summer. We can’t get that here, but I want to try an over/under with the stream and the Milky Way,” I say.

The shot proves to be a tough one to take. We give it about 20 tries using my camera strobes and then our headlamps, in and out of the water. Eventually, we find something that works. “Ok, this is it! Ready…headlamps on…headlamps off!” I tell Anne. We only use our headlamps to illuminate the stream for about 3 seconds or they are way to bright in the photo. “That was it!! Susanna is going to be excited to see this!” (See photo at top of blog!)

It’s our last morning at Waikolu. I want to give Anne and Amanda something to use for the Pacific Parks Inventory and Monitoring team, so we head over to the stream for some photos.

Getting this shot was extremely difficult. Rain, lack of sunlight, and tons of suspended particles in the water made for a frustrating photoshoot. I came away with this one, which I was happy with. Here is Amanda with some snails.

We go to a part of the stream that I find particularly photogenic- the old dam. It’s created a mini double waterfall. I want to try to get an over/under there, to showcase both the stream work and the beauty of the valley. Unfortunately, it’s raining. After a few dozen attempts at an over under, I hop in the neck-deep water for some underwater photos to document what we’ve been doing with the snails and fish all week. I wish that I could have had a little bit more time to figure out the best way to get a photo there, but Eric and I need to hike out today to get the boat ready to go tomorrow.

As a rainbow greets us on our way out of Waikolu, I reflect on my time at Kalaupapa. It’s truly one of the most beautiful and haunting places I’ve ever been. If not for this internship, I would probably never get to go to Kalaupapa. This is truly a unique place within the NPS system. With that, comes unique challenges. Eric is the man that makes it all happen. I have nothing but the utmost respect for him and the team that he brings in. He finds a way to get it done under less-than-ideal circumstances and difficult logistical challenges.

A rainbow goodbye as we leave Waikolu. My nice camera was locked away in the housing with a wet dome at this point, so I had to snap this with my phone!

As wonderful as my stay at Kalaupapa was, this marks a personal challenge during my internship summer. I am incredibly grateful for all the opportunities and experiences the internship has and will continue to provide. It feels very uncomfortable to admit personal challenges during my internship, in fear of being considered unappreciative. However, I can also feel the past 8 weeks of constant field and computer work wearing on me mentally. Furthermore, logistic challenges with my equipment along lack of internet and phone service can provide further stress.

I know that I’ll find a second wind and I think it will come at my at my next stop on the big island of Hawai’i at Kaloko-Honokohau. I’m a little disappointed to be leaving KALA. I wish I could absorb everything that is here for a bit longer, but I’m so excited to be going to the big island. It’s my absolute favorite place I’ve been in the Hawai’ian island chain.

With that, I say my goodbyes to Eric, Anne, Amanda, and Laurene at the airport and say thank you for all that they’ve done for me. I get on my 8 passenger plane to the topside airport of Molokai, and in true KALA style, I have to take 2 more flights to get to the big island!

Sunsets at Kalaupapa are special.