I’ve been on O’ahu for a few days. I arrived over the weekend and yesterday was a holiday, so I haven’t gotten in touch with the National Park Service team here yet. I’m strangely thankful for the break. It’s provided me much needed time for photo editing, blogging, and getting in expense reports. O’ahu has also felt like a second homecoming of sorts. I have many friends on the island, some of which I’ve been able to visit and some of which I’ve been staying with. By the time 11AM rolls around on Tuesday, my park work starts to begin. My phone whistles at me through the heat of the Hawai’ian fall.

Hi Shaun, can you get to the park by 2 PM?

A little bit of extra time on O’ahu allowed me to get out to Makapu’u lighthouse.

It’s Scott Pawlowski, Park Diving Officer at Valor in the Pacific National Historic Monument (VALR). VALR is most well-known for being the home of the USS Arizona, a US Navy battleship that was bombed and consequently sunk by the Japanese in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. It is also home to the USS Utah and Oklahoma Memorials, both of which suffered similar fates on that day. The significance of the attack is that it signaled the entrance of the US into World War II. The USS Arizona is the most symbolic physical entity our country has to pay homage to victims of that attack, but it also represents the soldiers lost throughout the war. Needless to say, this park experience is much different than going into the grandiose valley of Yosemite.

The USS Arizona memorial in Pearl Harbor is a shipwreck and a grave site.

I’m meeting Scott to go over my schedule for the week and get oriented to the resources and operations in the park. Pearl Harbor is still an active military base. The park is just on the outskirts of the base, so security at the front gate is tight. The guard sees me decked out in National Park Service (NPS) gear and asks, “Shaun Wolfe?” I tell him, “that’s me!” He lets me through and directs me over to Scott who is mid-conversation with a ticket booth employee. “Shaun, Shaun, good to see you finally! Sorry we couldn’t get you over here earlier. We’ll have to make some stops along the way, but let’s head up to the conference room.” Sure enough, Scott is either stopped by park staff or has to poke his head in a door almost every 10 steps. He is a busy man. VALR is one of the smallest parks I’ve ever seen but they have an exceedingly high visitation rate – approaching 2 million visitors a year – and co-manage the park with the military. This puts quite a bit on everyone’s plate.

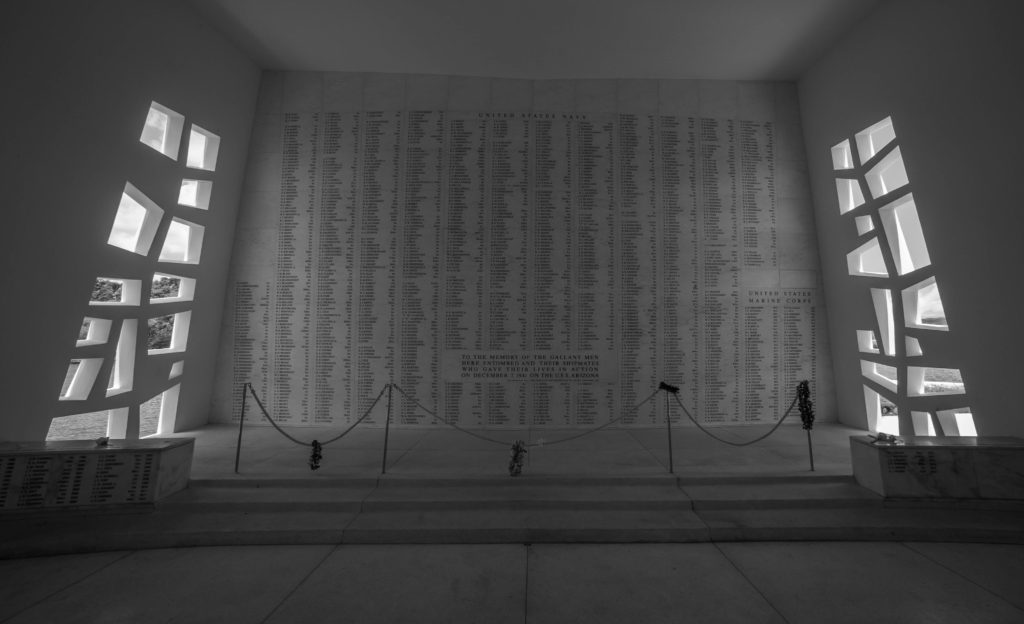

The far room of the memorial has names of all deceased USS Arizona soldiers carved into marble.

Up in the conference room, Scott gives me the lay of the land and starts letting me know what my opportunities will be. The dive program is getting audited on Thursday under the jurisdiction of Steve Sellers. Steve is a diving legend. He is a past president of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (the authority for all scientific diving) and the Diving Safety Officer at East Carolina University for nearly 20 years. He is now the Diving Safety Officer for NPS and is based out of Denver along side the Submerged Resources Center in Colorado. I missed him while I was there and jump at the opportunity to join the audit on Thursday. Saturday we are diving the USS Utah for sure, and possibly the USS Arizona as well. Sunday I will tour the park and the USS Missouri outside of the park (a WWII era ship which is still seaworthy and docked on the base).

Scott is a solid guy. He has a very endearing goofiness to him but can flip over to military-like seriousness when needed (this happens often given the park he works in). He is from coastal Washington (but don’t ask him to jump in cold water!), doesn’t sweat the small stuff, and is pretty intent on giving me as many opportunities as possible in the park, which I genuinely appreciate.

I was able to snap this photo between crowd rushes. This is the inside of the memorial. It feels strange being back here after 18 years away.

While we are waiting to hop on board the Navy boat that ferrys guests out to the Arizona Memorial, I notice that the diving here will be very different to the other diving I’ve done in Hawai’i. First and foremost, I haven’t dove a wreck all summer. Moreover, the visibility is much worse and the bottom will be silty in the harbor. Another thing that comes from being in a harbor is protection. “I haven’t had to worry about ocean conditions in 12 years,” Scott tells me.

We motor out to the memorial and I put my phone on silent and remove my hat. The USS Arizona is parallel to and just underneath the memorial. The memorial is a white rectangular structure that has a concave roof with lots of cut outs in it. Stepping into the memorial, the crowd goes silent. It’s quite the juxtaposition to the boisterous nature of the large crowds onshore. The USS Arizona is not only a shipwreck and a memorial to the dead soldiers, but it is a grave site. 1,177 men died on board when the ship was attacked and remain within the Arizona’s submerged hull. The memorial is a place of quite reflection, learning, and mourning.

Visitors view the ship from the memorial.

As we pass through the main hall, visitors gaze upon the deck of the USS Arizona. The ship itself is oriented exactly how it would have been above water. The hull sits perfectly on the seafloor and the deck is parallel to the surface. The deck is very shallow. Though it is hard to make out exactly what you are looking at because of the cloudy water. One salvaged gun turret stands above the water and provides a more visually relatable image for guests and interpretive displays give the visitors a better sense of the ship’s structure. There is a sheen on the water caused by oil that is still leaking for different compartments on the ship.

Visitors have a limited view of the ship, though it is better at low tide (seen here). Notice the oil sheen and black oil spots on the surface.

Heading to the back of the memorial is a separate room with all of the names of those who died on the ship engraved into a marble wall. Two things strike me in this room. One is the sheer amount of soldiers that died that day. Two is the list of veterans that survived the attack from the USS Arizona that have chosen to be buried on the ship. Scott and the dive team help run a program in conjunction with the military to put the remains of USS Arizona survivors in the hull of the ship to rest with their fallen comrades.

The Tree of Life shines light on a list of the soldiers that died long after the attack that have been cremated and buried inside the ship with their fallen comrades.

On our way back to the boat, we come across a cut out in the floor of the memorial, directly above the deck of the USS Arizona. “This was put in for the survivors that come back. It is a place where they can spend a more intimate moment with their crew members on the ship,” Scott tells me in a low voice. While the memorial is certainly set up to teach and cater to visitors, it was made for the survivors.

This space was built for survivors of the attack on the USS Arizona to have a more intimate connection with their fallen crew members.

Once we are back on shore, Scott shows me around the onshore grounds of the park. The interpretive work the park is doing in the way of signage, image displays, and exhibits is some of the best I’ve seen anywhere. “We want people to understand what happened and be able to put themselves in the shoes of the soldiers that day,” he says. As we move closer to a 3D map of O’ahu showing all the places on the island that were attacked, he tells me, “we also want them to understand that this really wasn’t an attack on Pearl Harbor, it was an attack on Hawai’i.” The Japanese sought to knock out as many of our naval and aerial resources as possible on the island, which are spread out between the coastline and the island’s interior.

The viewshed at Valor in the Pacific.

After a few more displays, Scott stops and looks up. Pointing to the horizon, he articulates that the horizon and the landscape around the memorial is a park resource as well. “Outside of a few piers, one low-lying bridge, and some houses, this landscape hasn’t changed much since 1944. Between our displays of where the planes came from and the view of the landscape here, we hope our visitors can imagine what happened on December 7th.”

As I say my goodbye to Scott, I comment on the uniqueness of VALR, “this is one of the only National Parks that I have ever been to where visitors come almost exclusively for the cultural resources of the park.” When most of us think National Parks, we think of massive mountains and big valleys filled with streams and wild animals. VALR is on a military base near a big city. It has murky water and no wildlife that visitors can see. People come here to learn about World War II in the Pacific and to pay their respects to the dead.

Sunset over the windward side of the island.

“Don’t be afraid of the red,” Steve Sellers says as he goes over the audit of the VALR dive program with Scott. “It’s all minor paperwork and data entry, easy fix,” he assures. Steve conducts audits of all 25(ish) park diving programs every three years to ensure that all national standards are met. Scott has brought me to the park to see the audit so that I can understand the nuts and bolts of running a dive program. The majority of the audit comes in the way of paperwork and making sure the information in the computerized diving management system is up to date. The Park Diving Officer, the Regional Diving Officer, Diving Control Board, and the park divers themselves all play a role in updating the system and keeping the program safe. I think the most interesting part of the dive program that I learn about during the audit is how these stakeholders form a check and balance system. Steve interacts with divers on the park dive team individually as well to get their take on the program and make recommendations about the program at a park, regional, or national level.

Steve Sellers (right) inspects some gear at VALR with Scott (left).

“I haven’t seen anything that makes me question the safety of your program,” Steve concludes. Scott knew almost everything that needed to get done before Steve came in thanks to the self-audit all Park Diving Officers are required to do in advance of Steve’s arrival. Even so, he is relieved to hear the news. The audit is really less of an intimidating, harsh consequential meeting. It’s more of a conversation about making the program safer and being in full compliance with national standards. This atmosphere, in my estimation, makes for a much more productive audit, stronger working relationships, and safer diving within NPS.

The USS Utah Memorial is smaller than the USS Arizona Memorial and closed to the public due to its location on the base.

I’m eating a larger bowl of oatmeal than normal this morning. I also woke up earlier to make sure all my gear is ready to go. Today is my day in the field, the day I get to dive the USS Utah and the USS Arizona. It is a privilege to dive each. Only the National Park Service and military divers are allowed to dive the ships. My dive buddy is Dan Brown. Dan works in concessions for the park, working out partnerships between groups that want to work with or in the park. He is also a member of the park dive team.

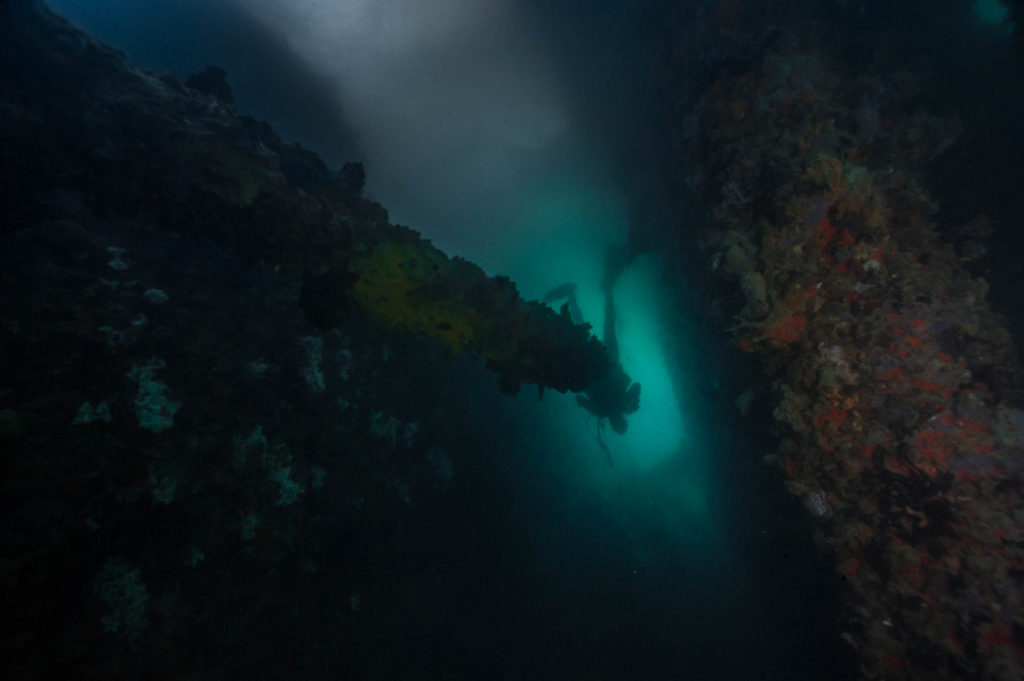

Subsurface on the USS Utah.

After a dive safety briefing and orientation, we drive over to the USS Utah. The Utah is laying on it’s side and the deck partially breaches the surface. Our plan is to swim along the deck at different depths to see as much as we can. We scale down the slippery algae covered rocks of the shoreline and descend upon the bow. The water is murky (about 10-12 feet of visibility) and the bottom is fine silt, which is easily disturbed and can make visibility much worse.

- A solitary gun on the deck of the USS Utah.

- An open hatch on the USS Utah.

- Much of the ship consists of impressive metal structure that is hard to make out.

- Tunicates and sponges galore! Everything on the ship is covered with these colorful little guys.

The ship itself is quite the site. There are so many open hatches on the deck. Some of them have ladders that run down below and others are so dark I can’t light them up enough to see what’s there. We continue swimming along and see gun turrets and some sort of crane on deck. Everything on the ship is covered in impressive sessile life, mostly tunicates and sponges.

A broken mast on the deck of the USS Utah.

Due to the orientation of the ship, it’s size (200 feet + smaller than the USS Arizona), and the damage it sustained during the attack, it can be hard at times to remember I am looking at a ship. Parts of the ship are so mangled that they look more like an indiscernible metal heap. As we make the swim back to the bow, we cruise the shallowest part of the deck. This is the part of the ship with the most in-tact features and best lighting. I can start creating an image in my head of what the ship really looked like and what life may have been like on board.

Open rooms like this helped me understand the USS Utah better.

Our next dive is on the USS Arizona. I once asked Susanna Pershern, photographer at the Submerged Resources Center, what her favorite wreck was to dive. She told me, “the HMS Fowey at Biscayne [National Park], it’s in-tact, historic…it’s beautiful.” Puzzled by this, I inquired, “what about the Arizona?” She smiled and said, “the Arizona is in a class of its own, you can’t compare other wrecks to it!”

Getting into the water at the USS Arizona can be tricky. You don’t want to draw attention to yourself, as the focus should be on the fallen. However, it’s impossible to control the curiosity of visitors when they see divers getting in the water.

Needless to say, I was excited. If Susanna, who has logged hundreds (if not thousands) of wreck dives says this is thee wreck, it must be pretty special. Of course it feels strange to say that I’m excited or that the diving the wreck is cool. In reality, the wreck is anything but “cool.” It represents one of the greatest tragedies in US history and is symbolic of World War II- the deadliest event in the history of the world.

Swimming between the USS Arizona and the memorial structure.

“You’re going to be the brightest, shiniest thing around when we get out there. The key is to maintain a low profile without ignoring the guests. We don’t want the focus to be on us, we want it to be on the soldiers that are on the Arizona,” Scott briefs me as we prepare to board the Navy passenger ferry that takes guests out to the Arizona Memorial.

Once we arrive to the memorial, we wait for all the other guests to get off the ferry and we stage our gear in our own gated corner of the floating dock. Dan and I stealthily swim under the memorial and descend onto one of the Arizona’s four gun turrets near its stern.

- Here you can see some of the original wooden teak decking on the USS Arizona. I saw this same decking when I visited the USS Missouri (see next image).

- Guns on the USS Missouri show me what the guns of the USS Arizona looked like in their heyday. Also, this teak decking is exactly what I saw on the USS Arizona. The USS Missouri helped bring the USS Arizona to life for me.

Because the USS Arizona sits perfectly centered on it’s hull in a harbor with little ocean movement, the deck is flat and holds many historical items (in addition to pennies, cell phones, and other items visitors drop that the park divers clean up). We find some of these items right away. An old shoe, a mason jar, a hair tonic bottle, old broken bowls. These items humanize the wreck. I’m looking at items that likely belonged to or were used by soldiers on the ship. What if a lieutenant used that bottle of hair tonic on December 7th thinking it was going to be another mundane day in the harbor?

- Because the orientation of the hull, historical items sit perfectly still on the deck of the USS Arizona. The Submerged Resources Center has tagged many of these items, such as this shoe.

- A hair tonic bottle from 1941.

- An old mason jar.

- Old bowls on deck.

We then descend on the starboard side of the ship and find a few portholes in the hull. Some of the portholes still have their glass windows. I can’t see through these portholes as they are significantly fouled. The glass got blown out of other portholes, which are about 8” in diameter. I can look into these and my powerful camera lights reveal surprisingly in-tact rooms. In the first room we look into, there is a table and an a sink, perfectly in place. In the next room, there is a clothing hanger, likely undisturbed since December 7th. It is both chilling and spectacular. I imagine how normal that day was until it wasn’t. They must have been so unprepared and unsuspecting, just going about their morning routine as usual. Seeing these rooms is one of the most powerful experiences I have had all summer.

The portholes of the USS Arizona.

Swimming further towards the bow, we pass the most in-tact gun turret on the ship, holding three giant 14″ guns. I swim along the guns to see get an idea of how long they are. I swim, and swim, and swim. The guns are nearly 20ft long, much longer than the water allows me to see all at once.

Sometimes you have to improvise! I didn’t have the light and extra diver I needed to get this shot, so I took my strobe out and held it in my hand. I couldn’t get my hand out of the shot as these portholes are only as big as my camera dome, but a bad shot is better than no shot! This allowed me to peer into the rooms within the USS Arizona.

Finally at the bow, we pass by the most damaged parts of the ship. Where the aerial bomb exploded in a gun powder magazine and ultimately sunk the ship. I begin to think about what my grandfather must have felt like on that day. Did he know that the attack meant that he would be serving on a Navy ship at the battle of Okinawa and change his life forever? How did my grandmother feel knowing his fate might be the same as the men that went down with the USS Arizona?

This is all a tip of the hat to the National Park Service staff. Their mission here is to maintain these “resources” (ie. the ship and it’s contents) in context. In doing that, they have allowed me to see a story from the past. Though truthfully, seeing the ship from underwater something very few people will ever get to do. Most people have to access the story through the videos and exhibits that the park has put up. While these are excellent interpretation displays, there is no substitute for seeing the ship underwater.

Open hatches on the USS Arizona often reveal staircases.

Back on the dock, we are putting our gear away and appease many guests by answering “what are you guys looking for down there?” many times over. We take the Navy ferry back to shore where I say mahalo and goodbye to Dan for coming in on a Saturday to dive with me.

I also say goodbye to Scott. I thank him for allowing me to dive at both sites. I wouldn’t have been able to dive without him and his team did not need to dive otherwise today. Furthermore, I sincerely enjoyed my time with Scott. He’s a great person to work with. He keeps his crew loose and laughing, yet also efficient and professional. “I’ll make sure I get you tickets to the USS Missouri for tomorrow plus anything else you’d want to do around here,” Scott says to me as I hop in my red Smartcar.

Filling this car with my dive gear, camera equipment, and personal belongings was quite the feat. Photo credit: Natalie Shahbol.

It’s my last day in O’ahu and I’m going to be a full blow tourist at Valor in the Pacific National Monument and the USS Missouri. I arrive at the park to grab my comp tickets thanks to Scott. After seeing the film about the USS Arizona and touring the memorial another time, I hop on the bus to go to the Missouri.

The spot on the USS Missouri where the Japanese surrendered to the US to end WWII in the Pacific.

On June 22, 1998, I was 7 and ½ years old on a surfboard in Waikiki, O’ahu and the USS Missouri was being towed into Pearl Harbor. The USS Missouri is one of the most decorated battleships in American history and its main deck is where the Japanese surrendered at the end of WWII. As such, my parents remember this as a special moment and my mom brought it up on the phone with me many times this last month, knowing I’d be going to O’ahu. Of course, I didn’t understand any of the historical significance at that age. I only remember thinking the accompanying fire department boats that were spraying water high in the air were awesome. Now at 26 years old, I know that my relationship to the Missouri is about to change dramatically.

Inside officer’s quarters in the USS Missouri.

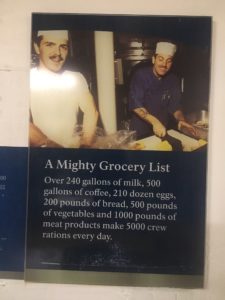

The first thing that stikes me about the Missouri is its size. It’s extremely tall and almost 900 feet long. Dan Brown advised me to block off 6-8 hours to tour the ship. Once I get on board, it’s easy to see why. Several decks of the ship have been turned into a museum, jam packed with displays and information. Every single room is an exhibit- officers’ quarters, kitchens, lounges, etc. Though the USS Missouri isn’t managed by the National Park Service, it compliments the USS Arizona, as the ships represent the beginning and end of WWII in the Pacific. Furthermore, after diving on the USS Arizona, the USS Missouri shows me what the Arizona was like in its heyday.

The guns and teak decking I saw on the Arizona come alive for me on the Missouri. The rooms I saw through the portholes in the Arizona’s hull are perfectly on display in the Missouri. With the entirety of the USS Missouri decorated as if it were underway with Navy soldiers on board (including sounds like thousands of people eating in the dining hall), I really begin to absorb the life that the young men on WWII battleships had.

- One of the command centers abor

- Was a requirement to have a mustache to cook on the Mighty Mo’? In all seriousness, that is an impressive amount of food!

Two things left a lasting impression on me after my visit to the USS Missouri. The first is the realities of war and how we talk about it as a country. Often times WWII is looked back on via triumphant and exuberant vignettes, like tanks rolling down the streets of a freshly-liberated Paris while young women are screaming praises at our soldiers. In reality, the war was the peak of human brutality. My grandfathers never spoke about the war. After going through some exhibits on the Missouri, it was easy to understand why. Soldiers were in constant and oppressive fear about being attacked. In battle, they often saw their best friends blown up. If they got to say goodbye, it was often to disfigured body parts.

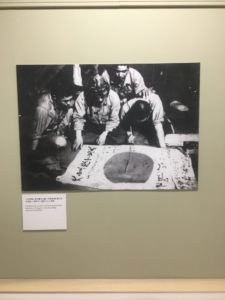

- Portraits of kamikaze’s. These Japanese airmen were no older than 27 and many were younger than 20 before going on their terminal missions.

- Japanese airmen check out a kamikaze good luck flag. My grandfather had a very similar flag. This gave me chills.

The second takeaway for me was the kamikaze exhibits. The exhibit have photos of Japanese kamikazes and letters from each back to their loved ones sent before their kamikaze mission. Some of their personal belongings were on display as well, mostly those recovered after their terminal mission. They were all so young. I tried to put myself in their shoes, being 18 years old knowing I was going to die on my next mission. I tried to put myself in the shoes of their loved ones, knowing they were going to lose their son, husband, or sibling. Many of these kamikaze pilots carried a Japanese flag with them on their mission that was covered in written good luck phrases. My jaw dropped when I saw this. My grandfather had a Japanese flag that was badly damaged and looked just like this. What exactly did he see in battle? What experiences did he have that he was so unwilling to speak about? I couldn’t help but imagine the horrors he saw when I saw that flag in the exhibit.

As I am scarfing down some pad thai at my final O’ahu dinner with 3 friends from Catalina Island that live on the island, I begin to reflect on my time here. Valor in the Pacific is an incredibly unique National Park Service unit. From the way visitation works, to the responsibilities of the staff, to the globally historic importance of the park, to collaborating with the military and others, I have never visited a place like it. I came to the park mostly excited to dive the USS Arizona and the USS Utah. It is a privilege to be able to do so and one that very few people will ever have. However, my experience was shaped by the introspective moments I had reflecting on our country’s past. This is the goal of the team at VALR. This is how they want their visitors to feel after they come to the park. It was an honor to work with the team here and if my experience is any indication, they are accomplishing exactly what they set out to do.

Catalina boys! (L-R) Ricky Nichols, Ben Castillo, Myself, and Bryan Silver. Ben and Bryan were gracious enough to let me stay with them for a few days and even took me out sailing!