A couple hundred years ago, the water off the coast of south Florida was not a good place to be a mariner. Fringed by submerged reefs, shoals, and islands, this treacherous coastline claimed many unfortunate vessels before the modern era of detailed charts and high-tech equipment. Many of these ships remain in these waters, slowly deteriorating from years of exposure to saltwater and biological activity, but still serving as a piece of history. Now, they act as a maritime time capsule, preserving a glimpse of the past underneath the warm waters.

These wrecks can teach us a lot about years past, but they aren’t completely safe in their watery resting places. Along with the slow breakdown of vessel materials from the salt and biological activity, these wrecks are also subject to salvagers and the occasional heavy storm. While the days of intense wreck salvaging are behind us and the protection of National Park waters can serve to keep them safe, these boundaries don’t do much to deter hurricanes when they decide to come to town. Recent years have brought some strong storm activity through the park, causing potential damage to these historic sites.

Biscayne National Park, located in south Florida just below Miami, is a 173,000-acre park that is 95% water. Protecting a number of distinct ecosystems, from mangroves to coral reefs, this park hosts boundless underwater sights. It also is home to a number of shipwrecks – 40 which have been officially documented but countless more likely lay undiscovered. Out of these, a selection of six of the most visit-able wrecks have been turned into the Maritime Heritage Trail – an opportunity for visitors to experience some of the Park’s treasured cultural resources. This trail, encompassing a wide range of vessel types, sizes, and eras, is a curated trip through some of the unfortunate maritime mistakes that occurred in Biscayne’s waters. By utilizing maps, brochures, and mooring buoys, park visitors can see, learn about, and experience these wrecks for themselves while snorkeling or diving.

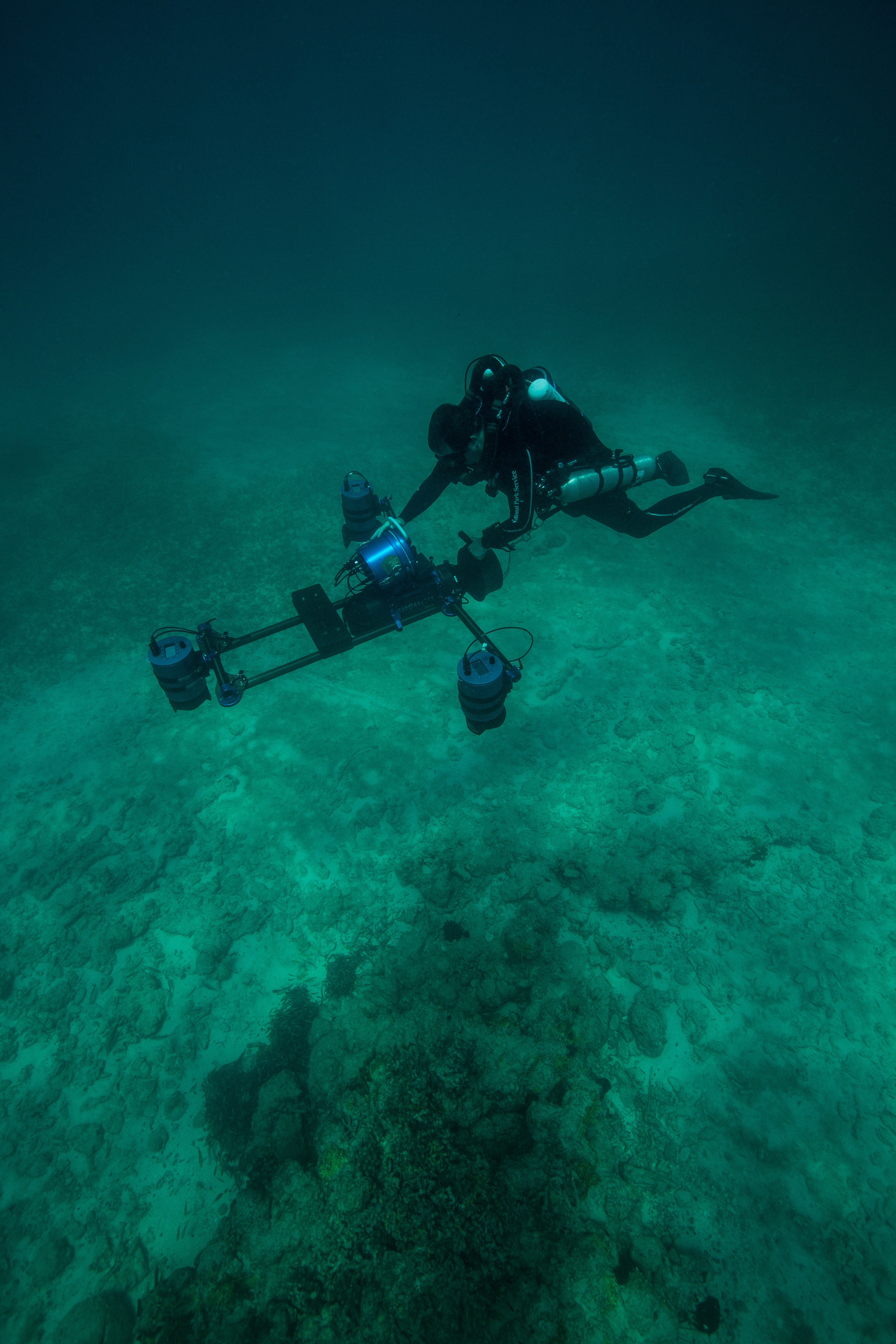

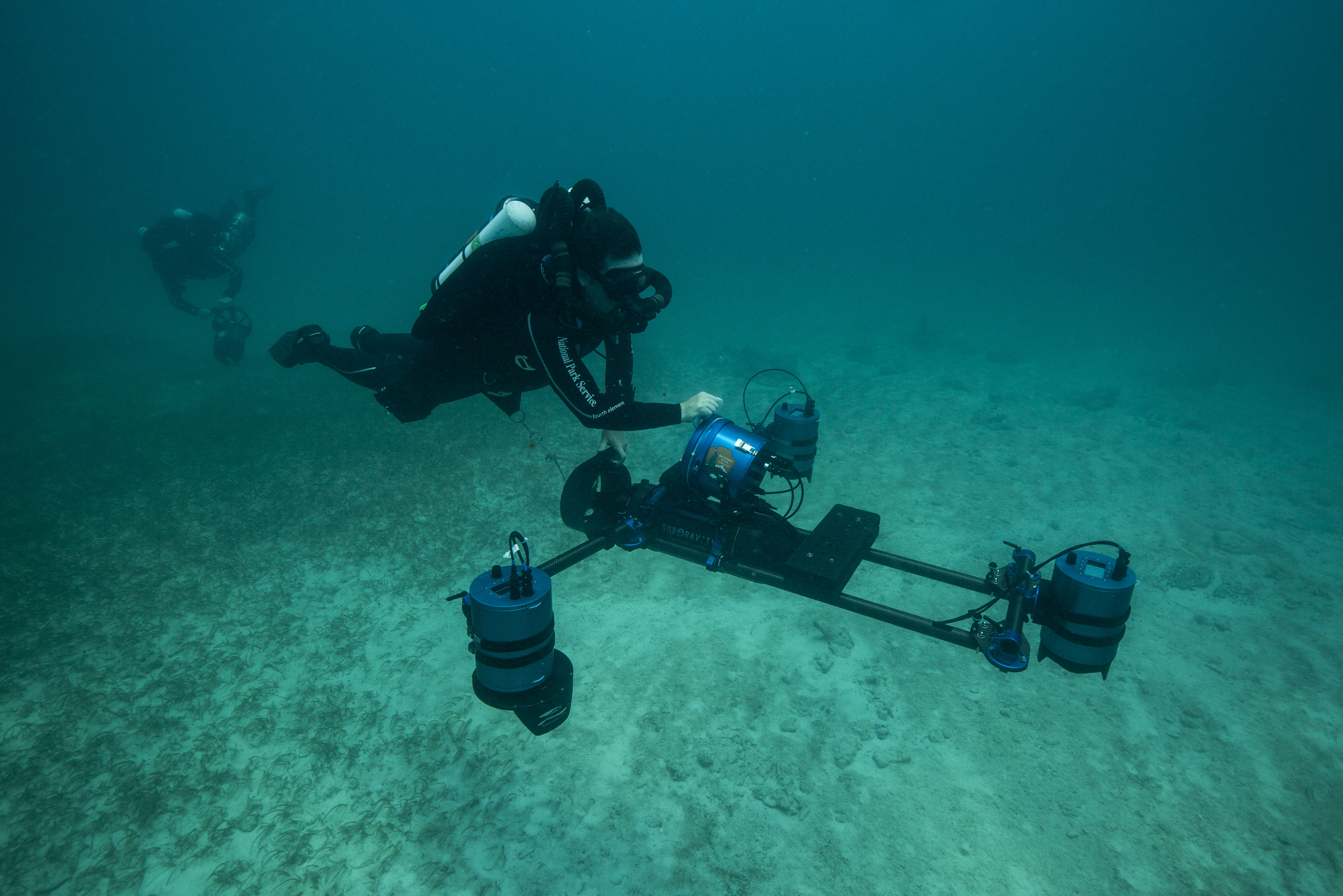

I was here with members of the Submerged Resources Center: Dave Conlin, Brett Seymour, Jim Nimz, and Matt Hanks. We were joined by Josh Marano, a talented maritime archaeologist who works the South Florida Parks. While here, we had a couple of objectives, all based around checking on the status of these historical wrecks post-hurricanes. Firstly, we’d be using the SeaArray, the SRC’s cutting-edge photogrammetry machine, to model the wrecks of the Maritime Heritage Trail. This would preserve them digitally as well as to start a baseline for continuous imaging-based archaeological assessments. We would also be conducting an assortment of measurements to learn about the composition and stability of the sediments around the sites – a way to learn how well they can preserve the wrecks and how much they change with the constant influx of storm-based wave energy.

Biscayne National Park has a very busy dive program, so while we unpacked and prepared our equipment (a myriad of dive, imaging, and survey gear) we tried to be as compact as possible and to make the smallest impact on the Park as we could. This was a bit difficult with the sheer volume of stuff required to do our work but we did our best, and only colonized a portion of the outdoor patio and roughly half of a large restroom. You have to work with what’s available, even if sometimes it means storing your dive gear next to a toilet – it’s all part of the adventure. Another important first step was to introduce ourselves to the Acting Superintendent of Biscayne, Joe Llewellyn. The SRC works directly for superintendents and park managers so its important that they understand the research or fieldwork, as well as just nice to share info with interested parties.

Once we had prepared all our gear, launched the SRC’s boat the Cal Cummings, and worked out our game plan, it was time to get out on the water. Our first wreck of the trip was the Arratoon Apcar, a wreck on the Heritage Trail in the far northern part of the park. As I mentioned earlier, the waters of Biscayne are full of shallow sandbars and shoals, so navigating out to our site for the day was a twisting trail through countless channels and around submerged hazards. The Arratoon Apcar wrecked in 1878 in especially unfortunate circumstances – this wreck is just a couple hundred feet from a lighthouse which was actively being built at the time of the wreck. The builders at the time were forced to watch as this vessel ran aground right in front of the light, which was just weeks from being complete.

Our goal here was to create a 3D model of the site using the SeaArray. Brett Seymour would operate the beast with Jim Nimz as his buddy, and I was tasked with documenting the process along with creating images of the wreck for the Maritime Heritage Trail’s online documents – websites, story maps, etc. This was a fun opportunity for me to work on my wreck photography – a skill I had just started to develop earlier this summer at Isle Royale – as well as to get a nice introduction to the warm Biscayne waters. This wreck itself was nice, mostly just the bare structure remained after the decades spent underwater but what was left painted a clear image of what the vessel used to be. Located in shallow, clear water with covered in invertebrate growth and surrounded with reef fish, it was a lovely dive.

After the dive on the Arratoon Apcar I headed out with Dave Conlin and Matt Hanks, the archaeologists of the SRC, to do some good old fashioned archaeology. For this we were joined by Josh Marano, maritime archaeological expert of the south Florida parks, whose local knowledge and expertise was indispensable when locating these wrecks and navigating the waters. We were to go to a couple more wrecks on the Heritage Trail to create GPS-based datums marking the site. This would allow the SRC to tie their newly created 3D models into maps, to place them accurately in their locations and allow for a full spatial understanding of the site in context to the map. This process involved a couple steps. First, a team of divers would descend on the site and locate two suitable locations on the fringes of the site. At these locations the divers would hammer in metal pins into the substrate, pins which would be incorporated into the model and a map to pair the two. Finally, it was time to take a GPS waypoint of the pins. This required a slightly different diver setup: as GPS signals are unable to travel through water, one diver would swim up to the metal pin underwater while towing along a buoy to mark their location. The other diver would swim along the surface following the buoy with a GPS in a drybag, taking waypoints when the buoy was directly over the metal pin.

I was able to join Dave, Matt and Josh on three more sites that day: the HMS Fowey, 19th century schooner wreck, and the China wreck. It was pretty special to visit four new wrecks in one day. These next three were full of surprises and artifacts. The China wreck site is littered with pieces of fine China (plates, dishes, bowls), pieces of its original cargo that still remain from when it wrecked years ago. The 19th century schooner was essentially two large piles of ballast (think big stones) but still had some of the original vessel material buried underneath. The HMS Fowey was one of my favorites: this was a 18th century British warship that sank in 1748.

This wreck is one of the crown jewels of the park with a secret location, limited dive access, and a restricted zone surrounding it to protect it from potential salvagers. This wreck is home to much of the wood siding of the vessel (protected from decomposition by being buried in an anoxic sediment environment), along with many exciting artifacts: piles of cannonballs (the ship’s shot locker, which rusted into an artificial reef after years in saltwater), a cannon, and a sword (amongst others). This is such a historically important wreck that it recently underwent a couple huge archaeological projects: one large excavation effort to uncover the site from its silty resting place in order to map and understand the full extent of the site, shortly followed by a large reversal of that process – covering the wreck in hundreds of pounds of sand in order to halt the decomposition process and to hide it from anyone who might damage it. This huge cover-up operation was unfortunately rather ineffective, as shortly after it was completed a hurricane paid the site a visit and promptly removed much of that newly added sand. This, again, was one of the reasons why our visit to this site was especially important: it was necessary to check in on such a historic cultural resource in the wake of powerful storms.

- Barrel stays from HMS Fowey

- Despite appearing as soley a home for dozens of lobsters, this chunk of reef is actually an heavily aged shot locker – hundreds of cannon balls rusted together after decades of sitting in the ocean

- A half-buried cannon

As well as adding the marker pins a final step to add to the models was site measurements. While the 3D models created by the SeaArray should theoretically be perfectly to scale, the SRC wanted to ground truth the data. To do this, they took an assortment of detailed measurements at the modeling sites -finding the lengths of conspicuous pieces of wreckage to check with the model later, as a way of proofing it. I joined the archaeologists for a couple dives to document this process, always great to see science in action.

The next couple of days were mixed with a combination of shooting site photos with Brett, Jim, the SeaArray, and with marking site GPS points with Dave, Matt, and Josh. I was able to visit four more wrecks, all with storied histories. There was the Mandalay, a luxury windjammer that ran aground in 1966 on New Year’s Eve and was quickly stripped of its fineries. The Alicia, carrying so much valuable cargo that it sparked a huge battle between 70 different groups of salvagers that lead to court battles and salvage law changes. The Lugano, who at the time of her wrecking was the largest vessel ever to wreck in the Florida Keys. The Earl King, a cargo carrier who ran aground in the Keys and was saved and repaired, only to run aground one final time in Biscayne 10 years later. It was a real pleasure to dive on all these sites with the SRC, and travel the Maritime Heritage Trail.

- Matt Hanks on the Lugano

- The wreck of the Alicia

- Brett Seymour and the SeaArray imaging the HMS Fowey

- The wreck of Arratoon Apcar

A couple of days into the trip we were joined by two new members of the team: Tara Van Niekirk, a graduate student and frequent collaborator with the SRC doing sediment studies at Biscayne, and Sydney Pickens, a recent Columbia graduate and Slave Wrecks Project collaborator getting an introduction to maritime archaeology with some of the NPS’s finest. They joined up with the archaeological dream team of Dave, Matt, and Josh, creating a talented group of professionals that I was honored to work alongside.

- Sydney Pickens and Dave Conlin taking measrements with Josh Marano

- Tara Van Niekerk taking sediment cores with Josh Marano

With this team we started to work on some sediment studies, part of Tara’s graduate research that the SRC was working on with her. These were conducted in order to learn more about the stability and composition of the sediments at the site – important factors responsible for preserving the organic materials of the wreck. Silty, mucky sites tend to be the best for preservation, as the muck creates an anoxic environment that greatly slows the decomposition process. By taking sediment cores from locations around study sites and carefully analyzing the layers, archaeologists can learn a lot about the site itself. Along with merely the sediment composition, they can look at the layering and see how it has changed over time: comparing and dating the layers between each other can tell them about the movement of sediments through periods of heavy storm activity, which can be helpful in understanding the abiotic factors affecting the site. Another useful measurement device that we would be installing were scour chains. These, essentially carefully marked and measured lengths of chain, are buried into the sand with a set amount of links exposed. When returning to the site at later dates, archaeologists can continuously check the chain to see if any more or less chain is exposed, telling them information about the changing sediment levels – if the site is being slowly excavated by weather, or slowly covered up.

The goal was to take do these measurements at a selection of the Maritime Heritage Trail wrecks. We started off with taking sediment cores at a couple sites, including some of my favorites like the HMS Fowey and China Wreck. The coring process was a cool one to witness. To start, a plastic coring tube was inserted into a length of metal pipe. This pipe was then smashed down into the substrate using a variety of tools, ranging from a mallet to this metal contraption used to drive in stakes (affectionately called a ‘whammer-jammer’ by the team). This core sometimes slid through the sediment with ease and other times took much more effort – it all depended on the substrate composition. Afterwards, the pipe was removed from the ground and the internal plastic core taken out. This was the finished sample, which was to go up to the surface to be sent out for analysis. I enjoyed seeing the sediment cores on the boat – sometimes distinct layers were visible even to my untrained eyes, and it was cool to see the differentiation in sediment types.

- Hammering the core into the sediment

- Have to make sure it’s fully inserted

- Removing the core from the outer housing

- Trimming the plastic casing to the size of the sample

After taking all our sediment cores, we moved on to the scour chains. While burying chains in sand may seem like a simple process, it takes a little more effort than you might think. In order to bury them deeply enough and without disturbing too much sediment, the team utilized a special dredge-like tool. Composed of a metal pipe linked via a hose to a water pump on the boat, this tool sends high-powered jets of water into the sand, essentially liquefying it and allowing the chain to be effortlessly planted into the ground. It was very fun to watch the team utilizing this tool at work, and I’m thankful that I was able to document the experience.

Interspersed in between all of this archaeological work I was able to still spend time with Team Imaging (Brett, Jim, and the SeaArray) as they worked to model the sites. I had a really good time working with these guys, especially as I was able to spend most of my time working to creatively photograph the wreck sites. I have fun with all types of underwater photography but it’s a particularly enjoyable experience when I’m able to truly spend time with a site to figure out how I think I can best capture it. It’s a welcome break from the often fast-paced world of documenting science at work, and I really like being able to slowly swim around a site and carefully scrutinize it to determine how I want to portray it. It’s also still thrilling to see the SeaArray cruise through the water, snapping away photo after photo of the wreck sites. I even got the chance to trade roles with Jim for a bit, trading my camera for a DPV, and spent a couple minutes following Brett around as his buddy.

One interesting thing that differed between our modeling work at Isle Royale and Biscayne was the exposure of the project. In sharp contrast to the remoteness of Isle Royale, Biscayne is in close proximity to a lot of people – just south of Miami and just north of the Florida Keys. In an area with such rich maritime archaeological history, there are a lot of people who were very interested in the SRC’s work. Because of this, we had visitors from other organizations come out almost every day to experience the team and the SeaArray at work. We were visited by the Florida Keys Marine Sanctuary’s maritime archaeologist Matt Lawrence, who joined us for a day of diving and site measurements. Florida Public Archaeology Network’s Sara Ayers-Rigsby and Rachael Kangas joined us to check out some sites and help with sediment measurements. Superintendent Joe Llewellyn came out to check out our work in his park one day and visit some wrecks. Jesse, an archaeological intern from Everglades National Park came out with us. A University of Miami graduate student working on science communication joined us for a day, who was excited to witness the modeling process that would make these offshore wrecks so attainable to the general audience. Most of all, everyone wanted to see the SeaArray in action and to watch this cutting-edge imaging tool at work at important archaeological sites. It was really special for me to see the far-reaching impact of this project, the interest and excitement it created, and the collaborative efforts taking place to get this work done. This solidified in my mind how important this work was, with so many different parties wanting to take part and help it along the way.

My first two weeks at Biscayne flew by before I knew it in a wild flurry of archaeology, shipwrecks, and imaging. I really enjoyed my travels down the Maritime Heritage Trail, exploring the submerged history that this beautiful park has to offer. I’m grateful for Biscayne National Park’s support of all our activities during these busy few weeks, Josh Marano for lending his time and expertise, and as always the SRC for having me along for their wild adventures. Now, I’m on to my next project at Biscayne National Park, one I’m especially excited for: working on my first magazine assignment with SCUBA Diving Magazine, documenting the Youth Diving With a Purpose program!