National Parks serve not only to protect and sustain the health of the environment but educate and engage people in the enjoyment and benefits of nature. In short, one might say from an anthropocentric point of view; that the overarching mission could be the conservation of nature for the perpetual education of and enjoyment by humans. As the birthplace of National Parks, the U.S stands out for its efforts and resources dedicated to the protection and preservation of the extraordinarily diverse ecosystems contained within its borders. From the deserts of Joshua Tree to the Arctic tundra of Denali, I am awestruck by the seemingly limitless opportunities to explore new and unfamiliar environments. With over 297 million visitors per year (to 423 individual parks), it is undeniable the importance of these protected natural spaces. However, the way that people use National Parks and learn about natural resources must be thoughtfully regulated and presented to ensure that future generations will be able to enjoy them for years to come.

Just south of Miami, an unassuming park lies tucked away in the mangroves, with only 5% of its area appearing above water as land. Upon arrival, Biscayne National Park is made up of a visitors center with a parking lot about equal size. However, it only takes a few short minutes to realize, as you hear speedboat after speedboat passing by, that there is a tremendous number of activities to offer here; you just have to look beneath the surface.

Overlooking Biscayne National Park from the visitors center

Biscayne National Park was established in 1980 and is a hub for marine recreation. On a given day, the park’s waters (which make up 95% of the park) are a destination for boating, fishing, diving, birdwatching, snorkeling, kayaking, canoeing, and guided eco-adventures. On a clear day, you can see the Miami city skyline and surrounding industry – which seem only to stop right at the gates of the park’s entrance and contrast the mangrove-covered keys in the foreground. As I settle in, I can see that this park provides important access to south Florida’s stunning coastline for local visitors. It is home to some remarkable natural and cultural resources, for which the park is an educational platform. However, I was immediately curious about how human interaction and use of natural resources within the park are monitored and controlled to reduce human impact while promoting and sustaining the park’s use. Over the next two weeks, I will join Biscayne’s extensive marine monitoring and inventory program to understand how this is done.

Wasting no time, I joined Mosaics in Science Diversity intern James Puentes and Latino Heritage Internship Program intern Nate Lima for recreational creel fishing surveys at the neighboring public marina as part of the Fishery and Wildlife Inventory and Monitoring Program. The overarching goal of this project is to engage anglers in collecting catch data through informal interviews, which will assist the development of sustainable fisheries regulations. Over several hours, we interviewed more than 40 anglers and collected catch data (e.g., species, size, location of catch, hours fished) as boats returned after a day on the water. In addition to meeting fishing enthusiasts and sharing awareness of the newest fishery regulations established within the park in 2020, it is here that I saw my first ever manatee! Taken aback by their size and constant presence in the marina, I can see just how vulnerable they are to propeller strikes (as several boats return from sea every 5-10 minutes and a cue of new arrivals are immediately launched just moments later). Seeing scars on their backs is a stark reminder of the delicate respect that nature commands in this shared space. A reminder that we are guests in their marine home. As part of the park’s biological monitoring team, our presence in the marina that day served not only to collect valuable data but to remind boaters to take care and do their part to preserve and protect the sensitive habitat and wildlife within the park.

Recreational creel fishing surveys with Biscayne National Park summer interns James Puentes and Nate Lima

Manatees graze at Homestead marina while weekend boat traffic passes ahead – calling into focus the human-wildlife interactions within the area and importance of education to prevent detrimental impacts. Photo: Nate Lima

Next up, I had the unique opportunity to join an all-female team of divers from the Wounded American Veterans Experience SCUBA (WAVES) Project in collaboration with NPS, the National Park Foundation, and SoundOff films for marine debris removal. We were joined by an all-female crew from Horizons Divers, NPS SRC archeologist Annie Wright, University of Miami Dive Safety Officer Jessica Keller, and Women Divers Hall of Fame veteran mentor Caron Shake. After speaking with last year’s NPS SRC intern, Sarah Von Hoene, I was eagerly anticipating this project and excited for the rare opportunity to join an all-female team on the water. After introductions over a group dinner, I was once again struck by the fact that although we each have divergent backgrounds, this project has brought us together based on a set of convergent goals and commonalities with regard to love for the underwater world, desire to enact positive change and eagerness to participate in conservation missions by diving with a purpose.

I set out on our first day, joining Biscayne National Park Biologists Vanessa McDonough and Shelby Moneysmith to meet the WAVES team at the dive site. As we exited the channel, into the bay, and beyond the keys, I’m caught off guard by the cheesy grin plastered across my face. My eyes fixate on my favorite color of blue amidst the vivid gradient in the water, a color I haven’t seen since my time as a Fisheries Resource Management intern with the University of Belize in 2019. Reflecting on my journey thus far, I remember not too long ago, as a recent HBSc graduate, when my ultimate goal was to somehow end up on a boat during working hours. I had no research experience, had barely seen the ocean for more than two weeks during my entire lifetime, and felt intimidated to break into such a seemingly oversaturated and competitive field. Now, I sit here dumbfounded, thinking: “Wow, I get to do this every day for the rest of the summer?” Let the fieldwork begin!

Over a week, the team collected 3,700 pounds of debris, including derelict lobster traps, fishing lines, hooks, and plastic waste. The mood on the boat was cheerful, full of inspired conversations about continued and future work to reduce marine debris and promote conservation. However, underwater, I felt heavy and somber. Particularly on the last day, when we moored up to an area frequently used by recreational anglers, I was overwhelmed and frustrated. Picking up fistfuls of monofilament while hoards of fishing boats float overhead, I could see the damage that years of debris build-up have caused as lines run through large barrel sponges and wrap tightly around branching corals. Lines left from recreational and commercial fishing (particularly the long, strong lines used to thread commercial lobster traps together), represent one of the biggest human impacts detrimental to marine conservation in the area. On a 45-minute dive, I covered no more than 20 square meters. The debris was that extensive.

Piles of abandon trap ballast recovered from the depths of Biscayne National Park

Marine debris was sorted, weighed, and properly disposed of at the end of each field day

While I am proud of our efforts this week, I acknowledge that to find a long-term solution, the issue must be stopped at the source. Awareness is an essential first step in ridding the “out of sight, out of mind” principle that often applies to the marine environment, and each person that joins in the efforts has a positive snowball effect. With the privilege of working in and accessing the beauty of the underwater world comes the responsibility to start and continue the conversation on how we can protect this vital ecosystem.

Next, I had the opportunity to join the Habitat Restoration Program team, working with biological science technicians Gabrielle Cabral, Cate Gelston, and Laura Palma, and MariCorps NPS intern Sophia Troeh, for my first experience with coral outplanting, in support of the University of Miami’s Rescue a Reef restoration project. Together, we embarked on the ambitious goal to outplant > 1,500 Acropora cervicornis (staghorn) coral fragments. At the conclusion of the first day, I snorkeled over the site for an aerial view of our garden, struck by the somewhat unnatural appearance of the monoculture of coral fragments pinned to the reef by globules of cement. However, on the second day, we planted fragments amongst corals that had been outplanted the previous year. They were thriving and had quickly covered up the cement “scabs” on the reef, turning into beautiful, healthy corals. Although my role in this project was small (considering the tremendous efforts that go into collecting and raising these corals to be ready for outplanting), I got to reap the benefits of one of the most rewarding stages in the process – just as the many volunteers do through Rescue a Reefs extensive citizen science program. A rapidly expanding field, coral restoration may not be the solution to the climate crisis; however, it is a targeted mitigation tool we can use to preserve ecosystem function when the cost of doing nothing is increasingly severe.

Outplanting coral fragments at Biscayne National Park in collaboration with the University of Miami’s Rescue a Reef program. Photo: Gabrielle Cabral

Week two at Biscayne was dedicated to training above water – I would be completing the Marine Operator Certification Course under the supervision of Maritime archeologist Joshua Marano. Together, we went through boat orientation, operating systems/maintenance, navigation, communication, risk management, survival and rescue, fire suppression, marlinespike, trailering, boat handling, and anchoring. A jammed-packed and, at times, challenging course, these skills will be crucial for the internship going forward. I look forward to continually improving my boat handling skills with this “license to learn,” bringing forward necessary tools that will help me integrate into new field teams as I travel through parks this summer.

Josh also took the time to introduce me to many of the park’s cultural resources, including artifacts from archaeological excavations that can be seen in the visitors center and stories from his experience at Biscayne over the years. Two wrecks, in particular, stand out for their significance within the park’s boundaries for reasons above and beyond pure historical value. First, the search for the Guerrero has drawn much attention to the park. It has also become a valuable educational, interpretive, and outreach tool, bringing volunteers and students from underrepresented communities to contribute to the uncovering and dissemination of the history of slave ships that have gone largely unwritten. Second, the HMS Fowey (wrecked in 1748 off the coast of Florida) represents an important landmark in the U.S shipwreck preservation case law. It was one of the first wrecks to gain attention federally and used as a case study in the establishment of protected archaeological sites, which were to be managed in the best interest of the public rather than privately salvaged and sold for profit.

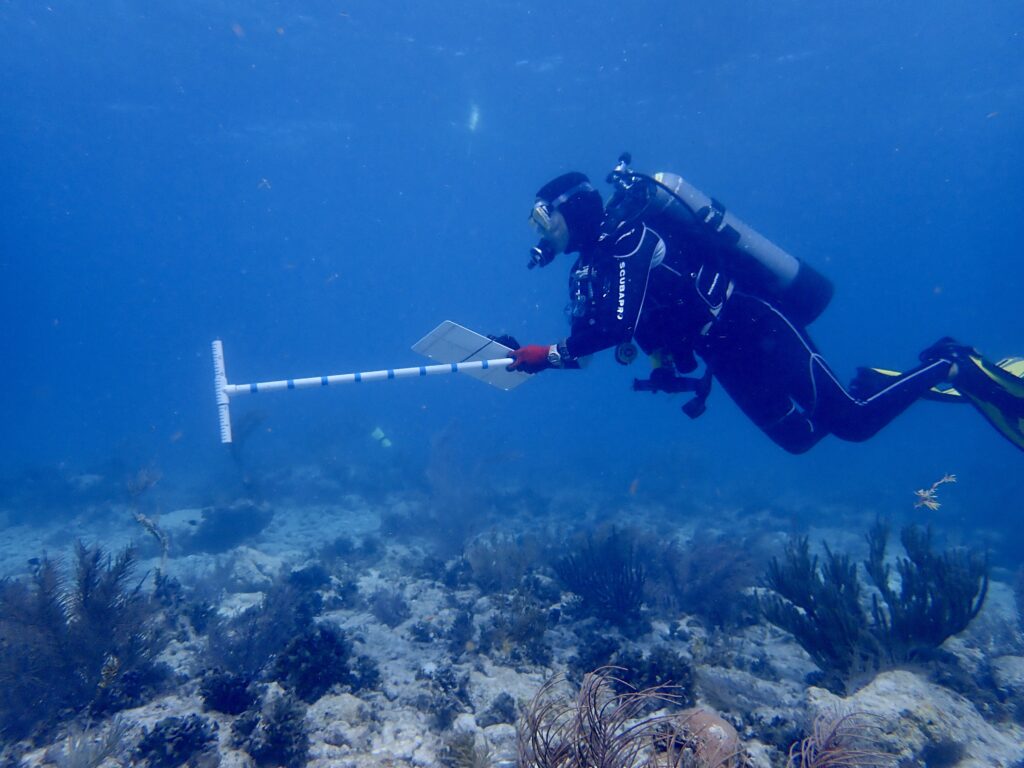

Last up on the seemingly endless list of potential projects to join at Biscayne, I reunited with Biologists Vanessa and Shelby, and biological science technician Morgan Wagner, for a day of roving visual surveys (used to characterize and inventory fish biodiversity, abundance, and habitat type). As a fish identification enthusiast, I relished the opportunity to familiarize myself with the Florida Caribbean fish residents (and snap some photos) while getting a great overview of the diversity of habitats within the park during our six dives that day.

Biscayne National Park biologist Vanessa McDonough surveying one of hundreds of sites they will do this year

After two short weeks, I can see that this park is managed by a hard-working and passionate team of employees, interns, and volunteers, who I had the great pleasure of working with. Thank you to Vanessa McDonough for facilitating, scheduling, and giving me the opportunity to learn from so many different people and projects during my stay. Thank you to my park roommates, James, Sophia, and Nate, for the friendly company, answering all of my questions, taking me for “emergency” food runs, and for welcoming me to the park on my first day with lionfish tacos and guac (!!) Thank you to Jessica Keller and Annie Wright for going the extra mile to include me in the WAVES project and socials (and showing me where to get the best key lime pie – which I proceeded to chip away at by the forkful after each field day). Thank you to WAVES and WDHOF team members Caron, Karen, Linsay, Char, Pat, and Maggie for the laughs, support, and conversations about our accomplishments and dreams – I hope to see you all again soon (fingers crossed for a DEMA reunion)!

After two short weeks, I can see that this park is managed by a hard-working and passionate team of employees, interns, and volunteers, who I had the great pleasure of working with. Thank you to Vanessa McDonough for facilitating, scheduling, and giving me the opportunity to learn from so many different people and projects during my stay. Thank you to my park roommates, James, Sophia, and Nate, for the friendly company, answering all of my questions, taking me for “emergency” food runs, and for welcoming me to the park on my first day with lionfish tacos and guac (!!) Thank you to Jessica Keller and Annie Wright for going the extra mile to include me in the WAVES project and socials (and showing me where to get the best key lime pie – which I proceeded to chip away at by the forkful after each field day). Thank you to WAVES and WDHOF team members Caron, Karen, Linsay, Char, Pat, and Maggie for the laughs, support, and conversations about our accomplishments and dreams – I hope to see you all again soon (fingers crossed for a DEMA reunion)!

As humanity’s presence and impact continues to expand and reach new corners of the globe, the opportunity to work alongside like minded individuals in the exploration, preservation, and conservation of our blue planet is one that I cherish dearly. Thank you to everyone who made my first park an overwhelming success, and to SRC and OWUSS for supporting me in this journey.

WAVES team members celebrating their honorary induction into the WDHOF Associates membership, during a night full of laughter, tears, and celebration.

It was great having you join the team! Have an amazing journey and I hope we see you again at Biscayne National Park!