As we lift off the airstrip at Key West International Airport, the pilot chuckles to himself. He asks me, “Is this your first time?”. I respond with bulging, excited eyes, “How could you tell?”, my nose barely lifting from its position pressed against the passenger side window of the empty 10-seater plane. A low-altitude 45-minute flight takes us 70 miles west of the southernmost point of the continental US, displaying aerial views of sea turtles, dolphins, shipwrecks, glistening “quicksand” (rolling, underwater dunes, continually shifting under the strong tidal current), and the Marquesas Islands. Although the seaplane is not the only way to get to this park, it undoubtedly provides the greatest “wow” factor for first-time visitors. Upon arrival, we circle the park’s perimeter, my eyes locked on Fort Jefferson – the cultural focal piece of this park and the largest brick building in the western hemisphere.

Aerial view of Fort Jefferson, located on Garden Key, as seen from the seaplane flying into Dry Tortugas National Park

I’ve arrived at the second park of my internship, Dry Tortugas National Park (est. 1935). Made up of seven small islands, it is one of the most inaccessible National Parks in the US. Due to its remote location, it can only be accessed by seaplane or ferry (both modes of transport are used by the park’s 120 daily visitors who enjoy a few short hours of swimming, sunbathing, birding, and picnicking before returning to Key West).

Fort Jefferson greets me as I step off the beached seaplane. With no land in sight for tens of miles, I ask myself, “why here?”. The fort was built to protect one of the most strategic deep water anchorages in North America, control navigation to the Gulf of Mexico, and protect the Atlantic-bound Mississippi River trade. I am eager to learn more about this massive masonry fort I will call home for the next two weeks, in addition to diving in the crystal clear blue-green water surrounding us.

Beyond the fort’s walls stretches miles of uninterrupted water. The moat wall or counterscarp was damaged during Hurricane Irma in 2017 – the park is working to implement repairs soon

Construction of the fort began in 1846 and continued for 30 years. Each of the over 16 million bricks used to build this fort was brought over by small wooden ships from the far reaches of the Eastern US. Given its remote nature, the construction of this fort was no small feat – in all of its striking architectural precision and grandeur. At its peak, over 1,700 men were stationed here, placing a significant demand for basic resources that cannot be found here naturally. Over time, the name of the island evolved (initially Las Tortugas – which translates to “the turtles’ and eventually changed to Dry Tortugas), calling into focus the importance of sea turtles in the diet of its inhabitants. It also warns passing sailors of the lack of freshwater and alternative food sources.

During a walking tour led by the tourist ferry company, I learned that the fort was used as a military prison during the Civil War. It also held four men convicted of co-conspiring in President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, including Dr. Samuel Mudd (who was instrumental in the fight against Yellow Fever that plagued the fort and was eventually pardoned from his sentence for his efforts in assisting sick patients).

Over time, I come to know new corners of the fort as they revealed their hidden secrets to me, often with the help of informal tours given to me by new friends and colleagues. From the bakery (which fed more than 400 people three times a day, known for its bread made of sticks, stones, flour, and sand) to Dr. Mudd’s cell (containing hand-carved water collection depressions in the ground), a cannon ball “cooker” (used to prepare hot cannon balls to fire at wooden ships), gun powder storage (signed with the names of ship captains who have visited the fort over the last hundred years), and remnants of Cuban chugs (makeshift boats used by immigrants who landed at the park over recent years), there is always more to uncover. With this growing cultural knowledge comes an increased awareness and appreciation for the historical significance of this fort from which we are conducting fieldwork. Each time I re-enter through the sally port (the one and only entrance to the fort’s interior) after a long, hot, salty, beautiful day underwater, I feel inspired and grateful for the opportunities I have been given to explore new places, perspectives, knowledge, and skills during this internship.

Overlooking Bush Key, which serves as nesting habitat for threatened bird species such as the Roseate Tern. Long Key (background) is the only documented nesting site for Magnificent Frigate birds in the continental US

Me with the obligatory picture at the park’s welcome sign.

As an avid backcountry camper, hiker, and aspiring explorer of all things tropical and dream-like, you can imagine my excitement upon learning that park Fisheries Biologist Clayton Pollock has organized for me to be whisked away to neighboring Loggerhead Key for my first two nights. An even more remote key within the park, it is covered in stunning vegetation and sublime white sand beaches, which frame a 150-ft brick lighthouse constructed in 1856. Brett Koch (Law Enforcement Park Ranger) drops me off at the dock with a bag of food and a jug of water, where I am met by University of Miami MPS intern Maddie Johnson. We have now effectively doubled the population of this island (n=2!) since interns typically conduct fieldwork independently on this key (although radio communication and emergency procedures ensure assistance is always a call away). An afternoon snorkel, sunset beach nap, a good book, and a frozen pizza are all I need to acclimatize to my new surroundings (a routine that would quickly become my go-to each evening) and prepare for the busy days of fieldwork ahead.

View of Loggerhead Key upon returning from an afternoon snorkel at one of the park’s finest shallow reefs

Named aptly for the abundance of sea turtles on the island, we quickly get to work the following day conducting sea turtle monitoring surveys. This work contributes to a long-term database on turtle nesting activities and hatch success that Park Service biologists have maintained since 1980. At 7 am daily, interns patrol the 2-mile long beach, skillfully interpreting turtle tracks to identify species, the direction of travel, and nesting activity. Nests are marked with carefully positioned stakes and GPS points and then monitored for the next 50+ days (watching for signs of hatchling emergence – indicated by a soft depression in the sand above the nest) to inform excavation timing. Nests are excavated after the incubation period to determine clutch size, hatching success, and any inundation, predation, or damage to eggs. In addition to contributing to the long-term monitoring program, Maddie will use this data, in combination with shoreline profiling, as part of her Master’s project, which aims to model and predict the effects of sea level rise on turtle nesting habitats under climate change scenarios.

University of Miami MPS intern Maddie Johnson excavates a loggerhead turtle nest. Egg cases and nest contents are removed, counted, and inspected for indications of hatch success and clutch size. Work conducted under FCW Marine Turtle Permit MTP#22-187.

Notice on Loggerhead Key marking nesting sites, reminding visitors to be mindful of disturbing nesting grounds and regulations enforced by the Florida fish and wildlife conservation commission

Patrolling the beach may sound like a relatively straightforward task, but in addition to the grueling conditions of a hot southern Florida summer day on a remote island with no running water, this island sees a tremendous amount of sea turtle activity (meaning it can take up to 7 hours to survey 2 miles of shoreline). To ensure accurate and meaningful data, interns must carefully document and decipher old tracks amidst the tens of new tracks created each night. Together, Maddie and I set a new record for the number of turtle activities recorded in one survey. We counted over 50 instances of false crawls (crawls where the turtle comes ashore but does not lay eggs in a nest), nesting, and abandoned egg chambers. I learned that although we counted 50 individual tracks, it doesn’t necessarily correlate to 50 individual turtles (considering that green sea turtles are very particular with nesting conditions and may come ashore several times in one night, over several days, before nesting). Nevertheless, these surveys indicate that Loggerhead Key is a crucial sea turtle nesting habitat that sustains a large population.

A “turtle highway” on Loggerhead Key. Following and interpreting these tracks becomes complicated as individuals overlap and tracks build up on the beach over time

An incoming and outgoing track made by an adult female green sea turtle on Loggerhead Key

Tracks made by sea turtle hatchlings upon emergence from the nest, in the direction of the ocean on Loggerhead Key

By the end of the day, it wasn’t only the sun’s heat that had us wishing for a short, heavy rainfall, but the desire for nature to effectively provide us a “clean slate” for interpreting tracks by washing away previously surveyed tracks amidst the overlapping maze. I am not surprised to learn that many of the current NPS staff began as sea turtle interns. Given the challenging nature of the work, it surely speaks to the work ethic, organization, and diligence of researchers in this role, making them an excellent addition to many NPS field teams going forwards.

Next up, the Natural Resources team arrives, and I meet Coral Biologist Rachel Johns and Coral biological science Technicians Karli Hollister and Evan Hovey. Together with Fisheries Biologist Clayton Pollock, we will spend a week sampling corals for a collaborator, Prof. Erik Sotka, from the College of Charleston. This large-scale project aims to assess coral genotypes for multiple species in the Southeast Region (including Dry Tortugas National Park, Buck Island Reef National Monument, Virgin Islands National Park, Salt River Historical Bay and Ecological Preserve, and Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument) and develop SNP chips/protocols for rapidly assessing and comparing genotypes for existing and novel corals, with applications for coral restoration. Lucky for me, this project will take us to some of the most stunning dive sites in the park, as we aim to sample several reefs per day.

A thicket of Acropora cervicornis (staghorn) corals and study site for the ongoing coral genotyping project. Photo: Karli Hollister

Photo: Karli Hollister

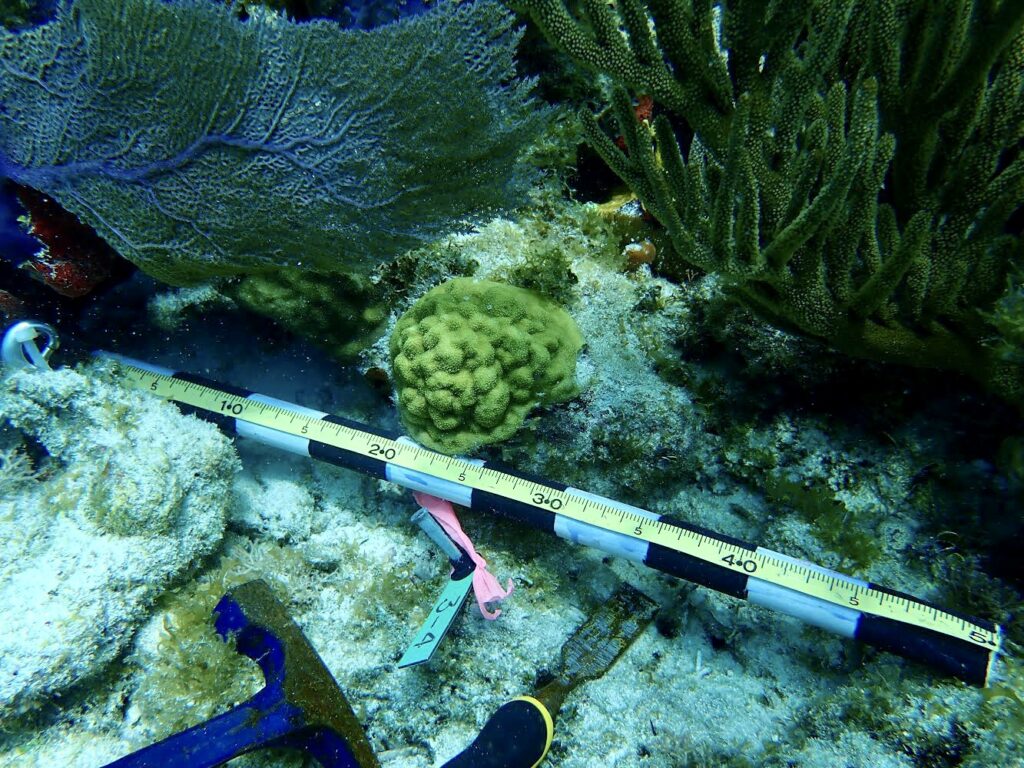

At first, collecting coral samples is a bit nerve-wracking (aiming to do as little harm as possible to the colony by carefully chipping off a 1cm piece). The work also involves juggling bags of tools, samples, a dive slate, scale bar, GPS tethered to a surface buoy, and camera underwater, often in shallow water with swell. However, by continually optimizing my gear setup, streamlining the sampling process, and becoming more comfortable with coral ID, I could effectively contribute to the team and start chipping away at the weeks’ worth of sampling they have ahead them.

Each coral sampled is tagged and photographed for future research

Not without its hiccups, working in such a remote location presents challenges regarding safety considerations, everyday operations, and equipment supply. Something as simple as a lack of plastic bags or generic sampling tags can limit the speed at which a project progresses until the next team arrives to supplement needed equipment. Nevertheless, the long days in the field, hours spent preparing and troubleshooting protocols, and post-sample processing flew by with such a lively team – cracking jokes and blasting tunes during surface intervals and at the tail end of long days.

As Clay, Rachel, Evan, and Karli depart the park and I await the arrival of a new field team, I use the transition as an opportunity to join visiting research ecologist and long-time US Geological Survey collaborator Dr. Kristen Hart on her team’s extensive turtle monitoring program. She is joined by several coworkers and collaborators, including Andrew, Haley, John, Bree, Amanda, and Brian from Cape Lookout National Seashore, USGS, Nova Southeastern University, and the University of Georgia. Together, we spend a night tracking nesting sea turtles on the nearby East Key by patrolling the beach every 30 minutes between naps under the stars. Nesting sea turtles are outfitted with a satellite tag to track their movements, flipper tags and Passive Integrated Transponders (PIT) for identification, and scute and blood samples for genetic and isotopic analysis. Dr. Hart holds the only permit to study sea turtles on this key (and she has been coming here for 15 years!). This information is used to gather baseline population data, delineate areas that may serve as inter-nesting, migratory, and foraging hotspots, and infer the trophic position of sea turtles within peninsular Southeastern Florida.

The following day is spent boating in slow circles around the shallow Garden Key Harbor while Dr. Hart and USGS Research Assistant Haley Turner stand at the bow with large dip nets at the ready. The goal for the day? To observe and catch juvenile green sea turtles for basic sampling and to understand the space use, relative habitat selection, and ecology of immature individuals. Many turtles we encountered were recaptures or resightings of individuals tagged in the previous years, speaking to the comprehensiveness of Dr. Hart’s work in the region. I settled into data collection while Kristen, Haley, and John did the challenging job of carefully catching these speedy youngsters. Having the opportunity to get up close with these resilient juveniles, I not only got to admire their brilliant shells and charismatic features, but also filled in many of my knowledge gaps regarding the life history, habitat usage, and behavior of this endangered species.

USGS researchers Dr. Kristen Hart and Haley Turner watching for juvenile green sea turtles in the shallows of Garden Key Harbor

Releasing juvenile green sea turtles after sampling. Individuals are marked with temporary paint for identification within a given field season. Work conducted under NOAA permits

Once the next rotation of NRM coral team members arrives at the park, including Coral biological science Technicians Amelia Lynch and Melissa Heres, Park Dive Safety Officer Jordan Holder, and National Dive Safety Officer Steve Sellers, we prep to embark on a critical mission for the week ahead. Underwater, Dry Tortugas is facing its own epidemic – a lethal disease that turns fields of previously vibrant, healthy corals upside down, transforming them into dwindling skeletons of their former selves stripped of live tissue – a sea of bones. The culprit? Stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD). As the disease’s epicenter, SCTLD first appeared in Florida in 2014, spreading quickly and causing high mortality. However, it wasn’t until recently, in May of 2021, that SCTLD was reported in Dry Tortugas National Park.

Armed with the best currently available science and practical knowledge on disease treatment and intervention, we spend the week delivering doses of antibiotics, in the form of a thick topical paste, to affected colonies. This is my first time coming face to face with a large-scale outbreak of SCTLD. I take a few moments underwater to acknowledge the mass mortality surrounding me. Applying the treatment is an intimate and quiet process. I gently press the paste into each nook and cranny of active lesions – outlining and essentially quarantining the region between bare bones (coral skeleton), sick tissue, and healthy. Treating an entire site within a day is challenging, even with a dive team of four. We must often opt to prioritize larger, more productive colonies for treatment, given our limited bottom time on open circuit diving equipment, leaving some colonies untreated. As a glimmer of hope, while scanning treatment sites, it is possible to see positive instances where the treatment has effectively controlled the spread of the disease within a colony. I send my well-wishes to the coral I have treated, which will likely need follow-up appointments, conducted by the hard-working team of NRM divers at the park for the foreseeable future.

Scientists are only beginning to uncover the detailed pathology of the disease and other phenomena impacting coral reefs today, including coral bleaching and restoration/heat-stress mitigation techniques. A standout in these efforts within Dry Tortugas National Park is research led by Dr. Ilsa Kuffner, USGS Research Marine Biologist, regarding the re-establishment of stepping-stone (i.e., crucial, reproductive, connected, restorative) populations to aid in the recovery of threatened, Acropora palmata (elkhorn) coral. This research, partially inspired by the recent discovery of new elkhorn patches within the park (beyond the previously documented single remaining site), uses an assisted migration experiment to assess coral survival, calcification, growth, and condition. Five different genetic strains of this species were planted across five sites (spanning 350 km) in Florida. Curiously, only in Dry Tortugas did all of the relocated corals survive, and not only that – but these individuals calcified approximately 85% faster than the few surviving corals transplanted to the upper Keys sites. With this information, Dry Tortugas may be a hope spot for re-establishing endangered elkhorn coral. Efforts are ongoing to restore a sexually reproductive, connected population, hoping to bring this species back from functional extinction, thereby promoting its regional recovery in the face of global climate change.

Newly discovered Acropora palmata within Dry Tortugas National Park, a threatened species throughout its range. Photo: Karli Hollister

As the long days turned into short weeks, my time at Dry Tortugas has come to a close all too quickly. Each day, I smile as a rush of excited visitors pours off the ferry, often having booked a ticket to the park weeks or months in advance. Each night, quiet falls on the fort, as visitors depart and I find a new corner of the fort to tuck into as dusk turns into starry night. Life on Dry Tortugas in the present day is serene, comfortable, and full of beauty – undoubtedly a stark contrast to the challenging conditions of the previous century.

I want to thank the DRTO NRM team and Dr. Kristen Hart for welcoming me into your field teams, providing new learning opportunities, helpful advice, and plenty of time underwater (and thanks to Karli Hollister for sharing photos and Amelia Lynch for the fantastic tour of the fort!). Thank you to Clayton Polluck for sharing your knowledge and experience with me (and providing an extended home away from home in Key West when life throws some curve balls…I am deeply grateful for your hospitality and support). Thank you to Curtis Hall for inviting me to speak at the Reef Relief summer camp (it was a pleasure to teach and learn from the excellent group of students this program hosts at the park each summer). Thank you to Cindy Hull for your help in Key West preparing for my visit to the park. Each of your time and generosity contributed significantly to my smooth integration and outstanding experience at Dry Tortugas. Finally, thank you to the National Park Service Submerged Resources Center and Dave Conlin for your hard work behind the scenes, and generous above-and-beyond support, making sure interns each year have nothing short of exceptional, unique, and highly valuable opportunities to experience and work in some of the finest parks the US has to offer.

As the summer progresses, I often reminisce on daydreams I had earlier this year, as my Master’s program was coming to an end – of either doing research, traveling, or diving upon graduation. Now, this internship has provided an unmatched opportunity to combine all three of these dreams, all wrapped into one, made possible by the support of NPS, OWUSS, and their collaborators. Standing in front of Fort Jefferson, a structure made not only of bricks but of bones of ancient corals; I feel proud to be a part of the NPS dive team and Park Service community, working to preserve fascinating and unique cultural resources while protecting and restoring the natural wonders it surrounds.