“Brandy, you’re a fine girl, what a good wife you would be”

We hear the 1972 single by Looking Glass in the distance. “That song is in the new one!” I exclaim referring to our conversation about the movie Gaurdians of the Galaxy II. “Who does that song?” Kaile’a asks us. Sallie quips, “I don’t know, I was too busy listening to rock n’ roll when that song came out. ‘What a good wife you would be?’ Gimme a break!” We all enjoy a laugh together and continue to load the boat for our day of diving.

After we idle through the harbor, the breakwater gives way to a extraordinarily calm ocean. “Welcome to Lake Kona,” Kaile’a remarks. I am on the island of Hawai’i helping the team at Kaloko-Honokohau National Historic Park (KAHO) with benthic (seafloor) surveys. We are surveying sections of coral reef within the park that Sallie Beavers (Natural Resource Chief and Marine Ecologist) and Kaile’a Carlson (Biotech) have been monitoring for an extended period.

Kaile’a Carlson hangs out at a safety stop.

The benefits to their long-term study are numerous. Seeing current functionality trends and finding drivers of the ecosystem allow the park to adjust their management strategy and protect their resources in the short-term. With long-term data, they can also look at historical responses to ecosystem disturbances (think giant storms, extreme warm/cool periods, and outbreaks of disease, invasive species, or predators). Thus, they can predict the way the ecosystem will change and how to best manage that in the long-term as well. In short, these studies help keep the park up to date (and potentially a step ahead) with what is happening to their resources.

Sallie and I are diving together today and Kaile’a is wo-manning the boat. Sallie is force. She is an incredibly self-motivated person and manages many people at the park. For this reason, and her “rock n’ roll” attitude, I am really excited to dive with her. We drop in to the warm and crystal clear waters of Kona coast and search for our starting point (marked by a metal bar and zip tie) for our survey. There is supposed to be one zip tie on the starting point and two zip ties on the ending point. The first metal bar we find only has one zip tie on it. I set my compass bearing to find the terminal point and begin to roll the transect tape (underwater measuring tape) out in that direction. Meanwhile, Sallie is looking at me like I’m crazy. Of course, we can’t speak to each other underwater on open-circuit SCUBA equipment, so she tries to communicate via hand signals. I’m not understanding some of her signals. I thought I was doing this right. It seemed simple enough. Then she points down at the metal bar we found and puts up two fingers. I get it.

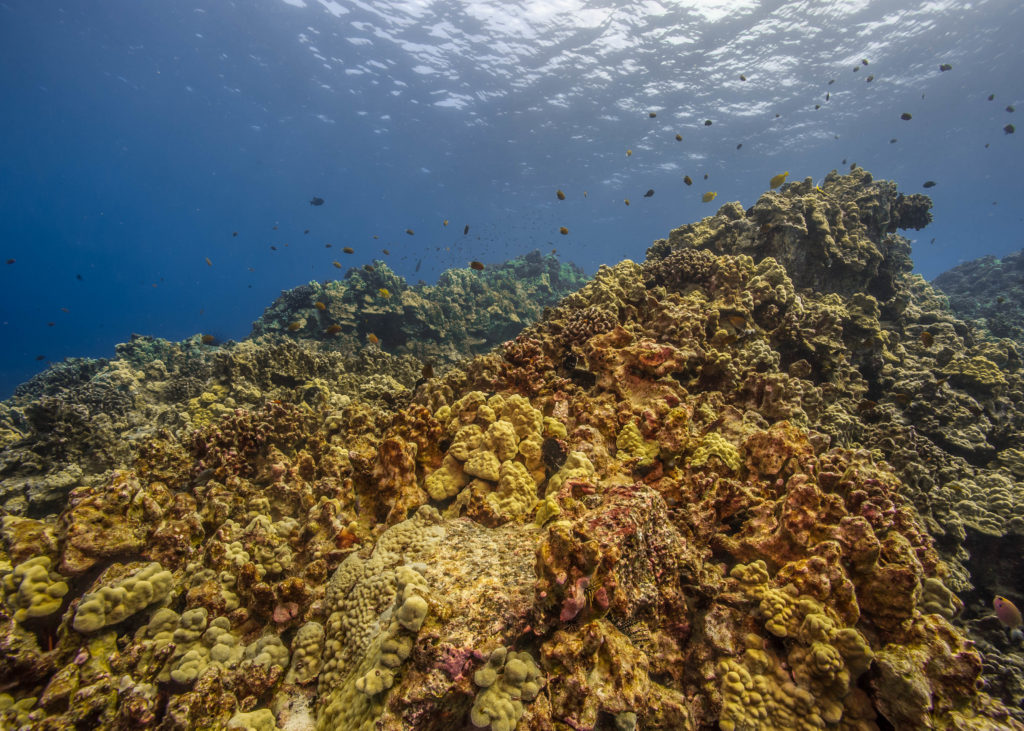

Sallie and Kaile’a told me the coral has been taking a beating at KAHO, but it looked pretty healthy to me!

We found the terminal pin but one of the zip ties had fallen off of the metal bar. Ahhh, the benefit of experience. Sallie knew this was the terminal pin after diving this site for years. Meanwhile, I was swimming the wrong direction, clueless.

Some soldier fish lurking on a wall.

The rest of our survey day goes smoothly. Sallie and Kaile’a both keep insisting that the coral reefs around the park are extremely degraded after a few serious bleaching events in the last couple years. They could have fooled me. The reefs in the park contain the healthiest and greatest abundance of hard corals I have seen this summer and I’m pretty excited about it. “Wow! That reef must be eating its kale. I haven’t seen anything that healthy all summer!” Sallie was kind enough to give me a courtesy laugh.

It’s 7:30 AM inside the air-conditioned NPS office at KAHO. I’m half-zoning out, looking at a poster showing the sizes of various fish when they reach sexual maturity when I hear Kaile’a shout, “Do they have red butts?!” Some anonymous voice from the other room replys, “Yeah, I think so.” “Those are ok, the ones with the red butts aren’t the invasive ones!” Kaile’a informs the anonymous voice that is looking at ants under the microscope.

Kaile’a in a red cave…no ants here!

The dive team at KAHO doesn’t only work on the water. Sallie and Kaile’a maintain and protect park resources on land as well. One pesky creature they have been dealing with lately is a tiny invasive fire ant. Not only can you hardly see these ants with a naked eye, but you can imagine working with “fire” ants has obvious downsides. These ants pack a punch in their bite. The worst part is, you literally can’t see it coming.

Sallie sent out an NPS team yesterday to set fire ant traps (popsicle sticks glazed with peanut butter). The teams then collected the traps and are now looking for fire ants on said traps. This will give them a spatial idea of where the fire ants are. Once they know where they are, they can try to manage them.

Of course, we aren’t working with fire ants today (though I did get to check out some red butted ants under the microscope). We are on our third day of benthic work. Today I get to get my camera in the water.

Getting the boat in and out of our parking space can be pretty tight (behind the engines, in front of the black boat).

After loading the boat in the Kona heat, we arrive at our dive site and Kaile’a and I hop in. Kaile’a is a string bean of a woman. She is as calm as the water of the Kona coast and has a very palatable sense of humor. We have a shared interest in photography, though Kaile’a is more science-based in her approach. Today, she is taking photos of a rectangular plot of reef. After we are done for the day, she will upload those photos to a computer software. The software will stitch them together to create a high-resolution 3D model of the reef. Kaile’a is pushing for this sort of monitoring in the park, because these 3D models enable NPS to see exactly how much the reef is growing/degrading each survey period and which corals are healthy or struggling. It’s a much more robust way to monitor and survey coral reef.

Kaile’a takes a 3D photogrammetry survey.

After the photogrammetry site is set up, I don’t have much responsibility. This means I get to take some photos of my own. While I’m taking a few photos of Kaile’a, we both notice a large patch of murky water behind us. We go to investigate and see that a semi-solid mostly-fluid solution is being puffed out (think the way an older man would smoke a pipe) of mostly dead coral heads. It’s clearly a spawning event, where some organism is broadcast spawning (releasing their eggs and sperm into the water column where they will eventually meet and fertilize). After several minutes of staring into a dead coral head, I find it. Scallops! I’ve never witnessed a spawning event like this on a dive. Once one scallop started the event, hundreds of scallops immediately followed. It’s an incredible site to see.

Look closely at this dead coral head for patches of murky water and you’ll see solid white gametes in the water.

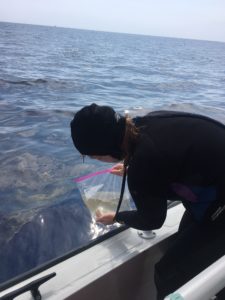

We are both pretty giddy about it. After a little bit more exploration, we head back to the boat and begin our drive into the harbor. On our way back in, we see a giant streaky yellow line on the ocean surface. “What is that?!” Sallie says as she slows the boat and turns around. “Might be coral spawning! We should go pick some up and take it back to the lab!” Kaile’a grabs a ziplock back, reaches over the gunnel of the boat, and fills the bag with the yellow-y water. “Two spawning events in one day?! Apparently the park service surveys are very romantic events,” I remark.

- A spawning event? Algae? Best to look at it back at the lab.

- Sallie Beavers takes a sample of the yellow substance on the surface.

Back at the harbor, we pull the boat out of the water and give the hull a deep clean. The boat will be on a trailer all night, so we need to clean off all the algae that has grown on it. Sallie starts cleaning the bow, while Kaile’a and I start at the stern. Eventually, I come up the bow and find some really hidden algae spots. Sallie sees me cleaning a section she already did, “did I miss a spot?” I respond jokingly while laying in a pool of water on the ground, “it’s no big deal! It’s impossible to expect everyone has these kind of eyes. They don’t call me ‘resident legend’ for nothing!” Sallie and Kaile’a crack up. “What we would we do without you ‘R.L.’?” Sallie says.

It’s 6:30AM. The light is just peering through my window and I can see my backyard. “MANGOS!” I shout. There is a mango tree in the backyard full of ripe mangos (one of my favorite foods). Today is going to be a good day.

- Rolling out the boom.

- The NPS boat drives off with the boom as the Coast Guard Auxiliary unfolds the rest.

Today is also going to be a unique day for me. No diving today. Instead, NPS, the US Coast Guard and the Coast Guard Reserves, and the Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation are having a training on how to deploy an oil boom. The park is involved in case they need to protect the park in the event of an oil spill.

After we unravel the giant boom, we put it in the water and our first team goes out on the boat to try and properly deploy it. The boom has anchors that attach to each end and then the boom itself sits on the surface as a physical barrier to oil spreading out of the containment area. The training turns out to be really valuable to all involved, as properly setting the anchors turned out to be more difficult than we thought.

Back at the office, I say my goodbyes to Sallie and the team. “Thank you so much for coming out R.L. We really would have been in a tough place without you,” Sallie tells me, continuing our joke from yesterday. I thank Sallie and Kaile’a abundantly for having me out. They were such a joy to work with and KAHO was undoubtedly one of my most enjoyable stops.

“I might head to Puako this afternoon to shoot some turtles,” I text Kaile’a. She responds, “you don’t have to go all the way to Puako! Go to the aiopio (traditional fish pond) in the park, you’ll see a ton of them!” I was sold. The park is much closer than Puako and getting photos of turtles in the park is a service to the park itself.

When you can see the turtles in shin-deep water, you know you’re in for a fun time.

Two hours later, I’m walking on the dirt path down to the aiopio in my dive boots with my 30 pound camera rig slung over my shoulder. After getting some intriguing looks from other park visitors, I “hop” in the water near the hale (traditional Hawai’ian house). I hesitate to say hop. It was really more of a crawl as the water is less than 2 feet deep. Visibility isn’t good, but Kaile’a was right- there are turtles everywhere. I would have to close my eyes to not see them. The best part is, they are incredibly friendly. The turtles I encountered in the Caribbean were giant (much bigger than the Hawai’ian turtles) but impossible to approach. The smaller Hawai’ian turtles would surely say yes to a dinner date with a friendly snorkeler.

I crawl along with one turtle for quite a while. This guy/gal really doesn’t mind me. In fact, he/she swam right over my camera dome at one point on the way to more delicious sea grass.

Visibility wasn’t good, but these turtles were everywhere.

Turtles are really charismatic animals. The general public loves turtles and it’s easy to get people to care about them. Bringing these turtles to life in my photos may help push public support to protect the parks, other places, and (indirectly) other species along the Hawai’ian coastline. At the end of the day, that is the best feeling I can go home with.

8 AM and I’m ready for some lava! Anne Farahi (whom I worked with at Kalaupapa National Historic Park) is based out of Volcanoes National Park and mentioned that I may be able to go out with a US Geological Survey (USGS) crew and sample some live lava. Needless to say, I was extremely excited about this possibility.

Akaka Falls is a Hawai’ian state park on the big island. I made a pit stop here on my way to Volcanoes National Park.

Anne hadn’t heard back from the USGS crew by noon, so I decided to head over to the Hilo side of the island in case the opportunity would present itself. The shift starts at two, so I have plenty of time. My first stop in Hilo is an important one. My sunglasses fell out of my tent when it got blown over in Molokai. Luckily, Anne and Amanda McCutcheon (another woman I worked with there) recovered them the following week in the backcountry.

“You are a saint!” I tell Amanda as she steps out of her ultimate Frisbee tournament to give me my shades. Life on the road just doesn’t feel right without some quality sunglasses!

Now that my eyes are adequately shaded, I drive to the far northern portion of Volcanoes National Park. Anne lets me know that she hasn’t heard from the USGS team and that going out with them is likely not going to happen. I quickly make a back up plan. $15 later, I’m on a mountain bike surrounded by lava fields. At the end of the road, the chase for live lava begins.

The lava fields make for a dystopian landscape.

The guy running the bike rentals told me to go right and look for smoke, so that’s exactly what I do. I charge through the endless black, dystopian landscape until I hit the first patch of smoke I see. I look around for orange glow and hope to feel intense heat, but there’s nothing. It’s just a sulfur vent. I jog over to the next steam plume. Again, just a sulfur vent. I do this for the next 3 hours and find many sulfur vents and no live lava. As the sun starts to fall, I come across a small family, “I think some people were headed up that way. Said there’s live lava!” I thank them for the tip and jog off towards the mountains.

The first thing I saw- lava flow into the ocean.

One hour later, I can feel the heat. I’m close. I stop and listen and can hear the crackling. I look that way and see an orange glow. Lava! I found it! It is incredibly hot. I can feel the soles of my shoes starting to melt and I am sweating profusely. I take a few photos and poke the lava with a stick (a Hawai’ian tip).

Live lava!! So excited to see this.

As night falls, I want to high-tail it out of there. One small predicament though- everywhere I turn, I am semi-surrounded by at least a little live lava. I channel my inner hummingbird and lightly run across the searing surface until I’m under the moonlight hiking back to the road. At the road, I’m captivated once more by the big lava flow going directly into the ocean. During the day, this flow is just a giant steam plume. At night, it is one of the most beautiful sights I have ever seen.

The omilu are beautiful fish. It’s not my greatest photo, but at least I got the fish’s color to show up!

It’s my last night in Kona. I’ve been in Kona once before this week and I really wanted to do the famous “manta dive.” The dive consists of divers sitting on the seafloor with dive lights pointing toward the surface at night. All the while, manta rays are cruising your head and chest bumping you. The last time I was in Kona, my dive got cancelled due to swell.

A crown of thorns sea star out at night. These stars can decimate coral reefs if their numbers are high enough.

Tonight is my chance. By 2PM I haven’t heard anything about adverse conditions, so I assume the dive is a go. Sure enough, by 5 PM I’m descending for my first dive. The first dive is full of wonderful tropical fish and my favorite Pacific jack, the omilu (blue fin trevally). In reality, the first dive is like buying an extra bag of popcorn when you arrive at a movie too early. The main show is the manta dive.

The manta dive lives up to the hype.

The manta dive is probably the most touristy thing I’ve ever done underwater. That being said, it lives up to its billing. There were 10 or more mantas gracefully gliding over our heads and petting us from time to time. They would dance beautifully in front of our lights, somersaulting to catch more plankton. Mantas are truly gentle giants. They dwarf any diver and have no interest or ability to hurt humans. If I could take someone who knows nothing about the ocean on a dive with any animal, the manta ray would be my pick.

A manta soars right over my camera

Kaloko-Honokohau energized me in a way few places have. After constant travel and field work for several months, I became a little worn down mentally. This internship is such an immense blessing and one that I could never complain about. However, I needed this recharge. Maybe it was Sallie and Kaile’a. Maybe it was the Big Island of Hawai’i. Whatever it was, I am extremely grateful for it. I leave the island with two new friends and feeling like I contributed to the park service. As much as I’ll miss KAHO and my backyard mangos (I think I ate about 30 in 5 days), I’m looking forward to my next stop in O’ahu where I will dive some historic shipwrecks and connect with old faces at Valor in the Pacific National Monument.

The mantas of the Kona coast.