In the early 1950s, developers and conservationists fought over the future of the northernmost keys of Florida. Located by Biscayne Bay, developers envisioned building hotels, roads, and a large industrial seaport to support the growing population. The battle between the two groups raged on for many years, until 1968, when Biscayne National Monument was created. Expanded and re-designated as Biscayne National Park (BISC) in 1980, the park protects the ecological and historical resources found in Florida’s northern keys.

Upon arriving in Miami, Shelby Moneysmith, the Regional Dive Officer and a biologist at BISC, picked me up at the airport alongside Herve, her husband who works for the University of Miami in coordination with BISC. After a filling lunch, I unpacked at park housing and accompanied Shelby and Herve for a quick stop at a popular fruit stand (Robert is Here). The once small, fruit stand started in 1959 but has since grown into a huge operation which sells a wide variety of fruit and delicious milkshakes. My mango milkshake was especially delicious!

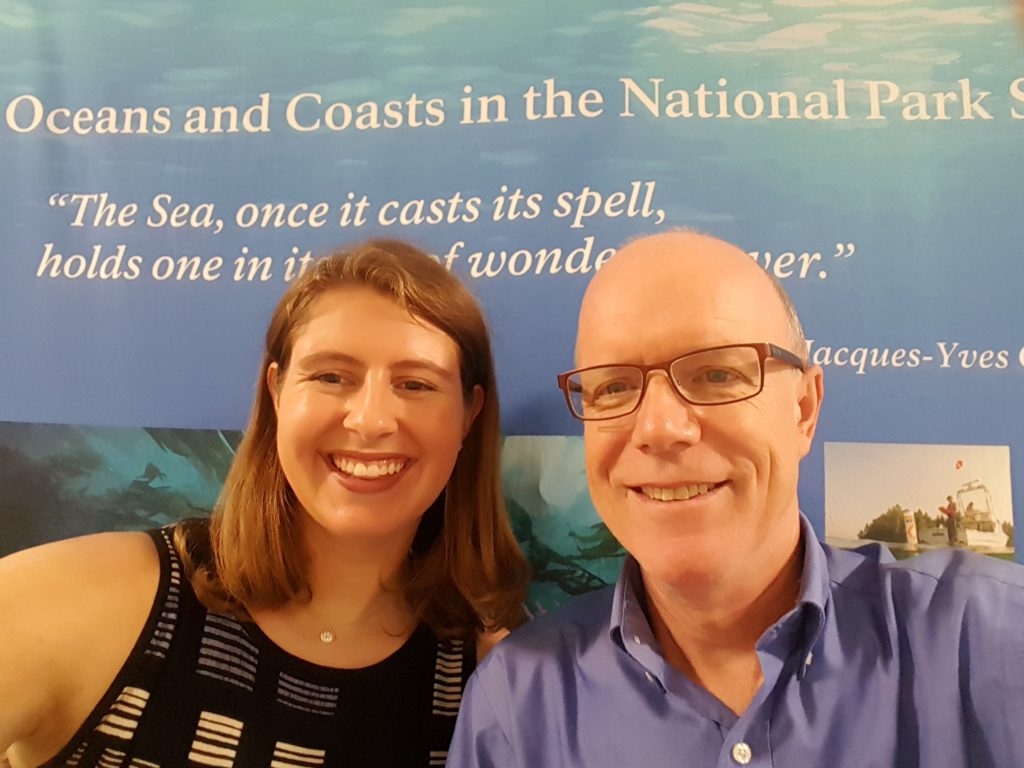

That evening, I met my roommate for the next two weeks. Originally from North Carolina, Devon received an internship to work with the interpretation department through the Historically Black Colleges and Universities Initiative. On Monday (Memorial Day), Devon and I took the free day to explore the grounds and the visitors center. While Biscayne National Park is approximately 180,000 acres, 95% of the park is water.

Due to weather, my dives on Tuesday and Wednesday were canceled. However, luckily on Wednesday, I was able to accompany Shelby and Elissa Condoleezza-Rice, a biological science technician, on one of their turtle nest monitoring trip. Every few days, six beaches along Biscayne’s keys are checked for loggerhead turtle activity. Loggerhead turtles reproduce every 2-4 years but often nest multiple times throughout the season (May-October). As an endangered species, the greatest threat to loggerhead sea turtles is the loss of habitat due to coastal development, predation, and human disturbance.

For turtle nest monitoring, we anchored near a beach, popped off the dive door, and waded towards the shore

After wading to shore at a few beaches and observing no activity, Shelby and Elissa found evidence of a false crawl on our fourth beach. When a female turtle crawls onto the beach to explore a nesting area but in the end decides to move on, this is characterized as a false crawl. At each false crawl, the surveyors marked the site, record location/site characteristics, and any additional metadata. This information prevents the surveyors from recounting the activity, and in case the false crawl ends up being a misidentified nest, they have the location for future monitoring.

Within a few more minutes, Shelby, Elissa, and I stumbled upon our first turtle nest. Compared to a false crawl, a nest was distinguishable because a patch of sand/vegetation was clearly disturbed as the loggerhead dug a chamber to store her clutch. At each nest site, we gently dug about an elbow deep into the sand to locate the clutch. Little contact was made with the eggs to limit the introduction of bacteria. To protect the nest, a screen was placed above the nest to protect the chamber from predation.

Hopefully, in about 60 days, little hatchlings will be crawling from this nest to the water

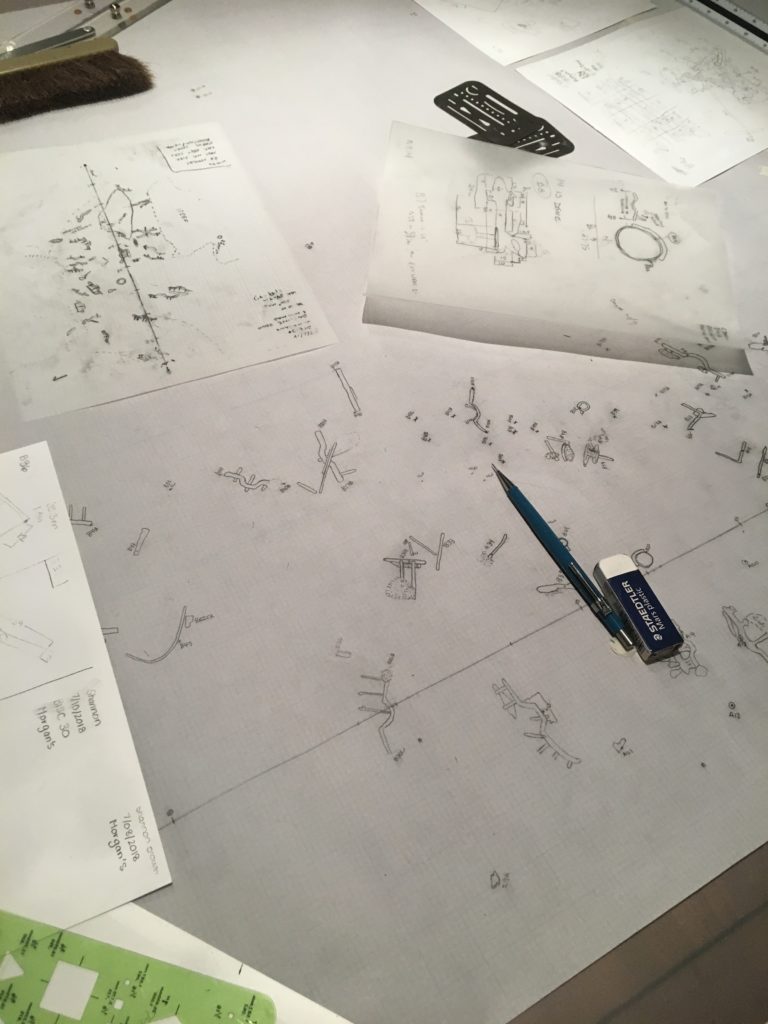

On Thursday, I finally participate in the diving operations at BISC. For two days, Arlice Marionneaux, an American Conservation Experience intern at BISC, and I planned on surveying several archaeology sites within the park’s borders. Checked every ~5 years for damage and looting, Biscayne National Park has over 120 archaeological sites. Most of these sites are known only by GPS coordinates. At each site, we used a map to locate pre-recorded wreck fragments including wood decking and ballast piles. Several sites had been damaged by Hurricane Irma, and on a few occasions, we were unable to find the marked artifacts.

Thursday was also filled with a multitude of boat problems. From radio issues to boat battery problems, our engine stopped working on a few occasions and forced us to throw anchor in a channel to prevent running aground. While stressful at the time, I learned a lot about boats and troubleshooting from Arlice.

On Friday, with a different boat, we headed out to finish several more archaeological sites. On our second of the four dives, Arlice and I visited the Lugano. Sunk on March 9, 1913, this British steamer was heading to Cuba with general cargo and 116 passengers when it grounded on Long Reef during high winds. Unlike the previous sites, the Lugano is a more exposed wreck site. While surveying the area, we observed a large diversity of reef fish, a nurse shark, and removed several fishing lines wrapped around gorgonians.

Located along BISC’s Heritage Trail, the Lugano is a well-preserved wreck inhabited by a variety of marine life

That evening, Dennis Maxwell, a park ranger at BISC, was kind enough to bring Devon and me on an evening kayak trip through the mangroves. With the visitors center in the background, Devon and I took off on the crystal clear water as the sun set over BISC. As we rounded the corner of a mangrove, we observed brown pelicans dive-bombing mullets riddling the shallow waters. To evade the pelicans, mullets jump out of the water. From our fluorescent orange kayak, the show as pretty spectacular.

Definitely one of the best ways to spend the evening at Biscayne National Park

Saturday morning began with a knock on my door. Terry Helmers, a volunteer at BISC for 31 years, asked whether I wanted to spend the day assisting with mooring buoys. With no weekend plans, I immediately jumped at the opportunity. Throughout BISC, there are 40+ mooring buoys along the heritage trail and various other locations to allow visitors to easily explore their park without damaging the marine habitat below. Replaced every year, these buoys can get damaged by hurricanes or boat engines. Mostly by freediving to 10-30 ft, Terry and Ana Zangroniz, another volunteer, spend several weekends at the beginning of the summer season replacing the buoys. While I had experience freediving for fun, I struggled to stay down for extended periods of time while also expending energy to unscrew bolts and remove caked on organisms. Terry, on the other hand, could unattached a buoy and bring it the surface in one breath. It was beyond impressive!

Replacing a float underwater to mark the location of a future buoy on the Heritage Trail – PC: Ana Zangroniz

In addition to replacing buoys at six sites, Ana and Terry let me snorkel the Mandalay. Sunk in 1966, this luxury-line from the Bahamas to Miami hit a shallow reef. All 35 passengers were rescued and scavengers later stripped the vessel. Sitting in shallow, clear water this well-persevered wreck is teeming with fish life. At the surface, hundreds of chubs surrounded you as you explored every small crevice of the vessel. In addition, I saw a midnight parrotfish. While relatively common in Biscayne National Park, when in Bonaire, I was the only member of my marine station to not see a midnight parrotfish after living there for seven months. Finally, after traversing the dang Atlantic, I could finally check a midnight off my list!

Unintentionally, we also collected a large amount of marine debris while out for the day. With limited fishing regulations and a crowded metropolitan city nearby, Biscayne has a sizable amount of marine debris. From plastic bags floating along the surface to abandoned crab traps scattered on the bottom, Terry, Ana, and I collected what we could.

Following a relaxing Sunday, I traveled out again with Elissa and Hayley Kilgour, an NPS intern, to check for turtle nests on Monday. After observing Shelby and Elissa the previous week, I was excited to correctly identify two nests myself during the day trip. While returning to the boat, we also saw five juvenile blacktip reef sharks swimming through the shallows. In the shallows, we commonly saw stingrays or tiny fish but sharks were definitely a treat.

Aren’t they adorable? – PC: Elissa Condoleezza-Rice

On Tuesday, I assisted with the ongoing marine debris study. Previously, transect markers/floats were placed at 12 sites through the park for a lionfish removal study. After the study was complete, the natural resources department decided to use these sites to study the accumulation of marine debris. Marine debris is collected from each site once a year and the amount/type is recorded to estimate the overall accumulation. Every 6 months, markers are cleaned and damaged floats are replaced. While diving with Vanessa McDonough, a biologist at BISC, we were met with strong currents and a float bag that decided to prematurely travel to the surface. Fortunately, we managed to check the markers and to spear a few lionfish along the way.

Lionfish are carnivorous fish native to the Indo-Pacific. These beautiful fish were popular ornamental fish which were either intentionally released in the Atlantic and accidentally released due to storms. In the Atlantic, lionfish have no known predators, reproduce year-round, and compete with native fish for food and space. At BISC, biologists spear lionfish in hopes of reducing their numbers at the park. At the end of our day, we measured the total length of each lionfish and stored them in the fridge for future interpretation programs.

Elissa measured each lionfish while carefully avoiding their 18 venomous spines

After an eventful day in the field, I was starving. Jay Johnston, BISC’s education program coordinator, was kind enough to invite me and several other employees and interns to his house for Taco Night. Our evening was filled with chips and salsa, scrumptious tacos, and great conversation.

With Amanda Bourque, an ecologist for BISC, as my dive buddy, we completed two more marine debris site dives on Wednesday. Since these sites are apart of an ongoing study, we were not allowed to pick up any debris within the transect. Already within six months, these sites were covered in stray lines and crab traps that were hard to resist collecting.

Blue skies and calm waters….ready to dive!

Thursday was spent assisting with goliath grouper survey dives. Relatively uncommon within BISC, at previously chosen locations, 20 min roving diver surveys are used to search for this critically endangered species. Unfortunately, during our four dives, a Goliath was not observed. We did, however, manage to spear a bunch of lionfish even one that decided to hid under Elissa’s legs mid-capture.

My final day was spent monitoring the turtle nesting beaches. With no new nests, Elissa, Hayley, Suzy Pappas, and I decided to perform a short beach cleanup on Tannahill. Suzy runs a non-profit organization called the Coastal Cleanup Corporation whose mission is to remove marine debris from Florida’s coast and educate the public. She volunteers with the turtle monitoring group at Biscayne and often sponsors beach cleanups throughout the year. During our quick 30-min beach cleanup, the four of us collected 10-12 full garbage bags of trash ranging from glass, buoys, and microplastic.

Cleaning up the trash and hopefully making more space for turtle nesting – PC: Suzy Pappas

After returning to headquarters and disposing of the trash, I was greeted by several individuals from the natural resource management department. Apparently, while Herve and Austin were collecting samples for water quality analysis earlier that morning, they came across a 3 m Burmese python hanging off the buoy about 1.4 miles offshore. Vanessa, Elissa, and Herve worked together to restrain the invasive species and get an accurate length measurement. My fear of snakes definitely prevented me from jumping in to help wrangle the creature.

Vanessa, Herve, Elissa, and Hayley handled the ~17 lbs animal

In the early hours of Saturday morning, Shelby and Herve drove me to the airport so I could continue my adventure. Three flights, lots of snacks, and almost a full day later, I would arrive in Honolulu, Oahu. From there, I would take a small plane to my next destination, Kalaupapa National Historical Park.

Thanks to all the great people who made Biscayne National Park feel like home for two weeks!

Quick facts about BISC:

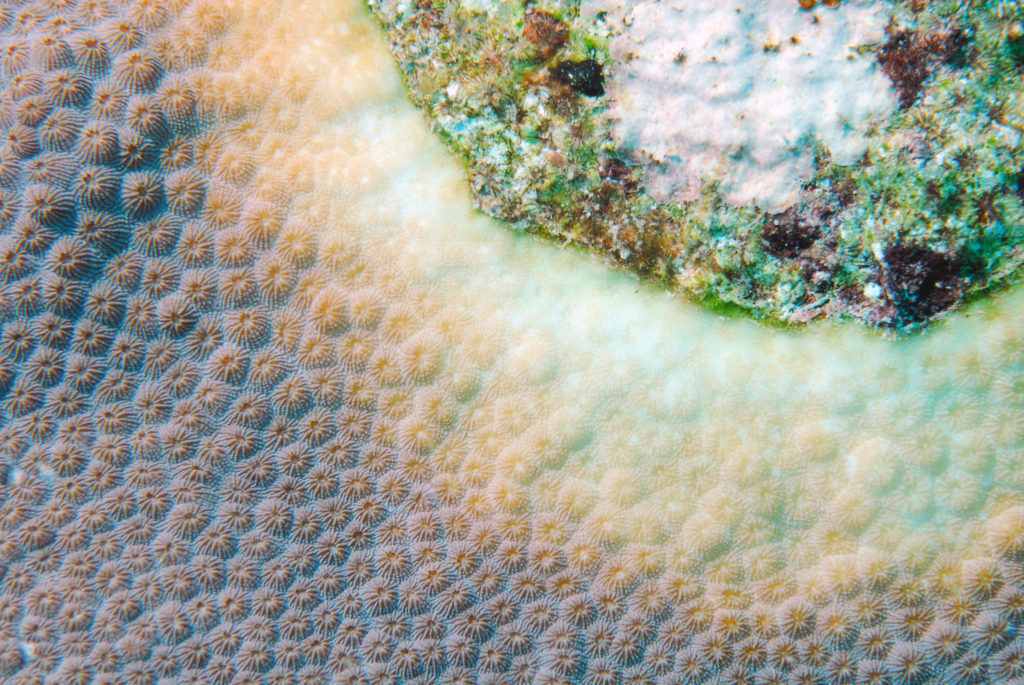

- Park has four distinct marine ecosystems: a fringe of mangrove forest, southern expanse of Biscayne Bay, northernmost Florida keys, and portion of the third largest coral reef

- Fishing and other harvesting activities are dictated by state law within the park boundaries

- Home to many protected species including the Schaus swallowtail butterfly, American crocodile, five species of sea turtles, and elkhorn and staghorn coral