Hello! My name is Griffin Hoins and I am honored to have been selected as the 2023 Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society® National Park Service Research Intern!

For almost 50 years OWUSS has been supporting young divers as they discover the diversity of opportunities that exist within the underwater field through scholarships and internships. The NPS research internship is sponsored and supported by the Submerged Resources Center which uses its network of connections with other NPS dive programs to craft an itinerary for one lucky intern to experience diving in the US national parks. I will engage with and learn from dive professionals: researchers, biologists, photographers, public safety divers, and archaeologists across the country. I cannot express how excited I am for my summer. I will be blogging about my experiences, so please follow along to hear about some of our amazing parks, and the work being done by the NPS dive community to preserve and protect our cultural and natural resources.

A little background on me, I was fortunate to grow up surrounded by large trees, tall mountains, and the Pacific Ocean on a small island in Washington state. My childhood was made up of hiking and camping with my mom in Olympic National Park, exploring tidepools, sailing around the San Juan Islands with my grandparents, crabbing and clamming for dinner, and swimming on summer nights in a sea of bioluminescent plankton. At the time I was oblivious to the effect that my environment was having on me. Now looking back, it is clear how my upbringing shaped me and directed me on a path centered on the ocean.

It is the end of winter when I get the news that I have been selected as the NPS intern. I am absolutely elated, and I ride that high through an unusually warm Washington Spring as I prepare to start my adventure in New York City.

I fly from Seattle and get situated by getting a pumpernickel bagel, bacon, egg, and cheese and sitting under the Chrysler building, my favorite building in New York.

My first stop on this intern journey is New York City for the annual OWUSS awards weekend. Every year the society brings together new scholars, interns, alumni, and supporters for a celebration of the previous year’s recipients and their achievements. It is the time to introduce the 2023 cohort, and meet the ocean champions connected to OWUSS. On top of that, the weekend is followed by World Oceans Week where we are invited to attend events and lectures held at the Explorer’s Club as part of the “Blue Generation” an initiative to engage younger people in ocean issues and foster the next generation of stewards for our Blue Planet.

The first event of the weekend is a dinner at The Explorer’s Club. On my way to the hotel to get ready, Shaun Wolfe, one of my OWUSS coordinators, reaches out to meet up in person. With him is Hailey Shchepanik – Shaun was the NPS intern in 2017 and Hailey is the 2022 intern. They welcome me into the family graciously and their enthusiasm gets me hyped for my summer as they swap stories until it’s time to get ready for dinner.

I will be spending most of my time this upcoming week at the Explorer’s Club. The club itself is a mix between a natural history museum and an upper east side 19th-century mansion. Once a home with an impressive art collection, it is now the headquarters of the Explorer’s Club and its many artifacts from historic adventures and expeditions. The club has supported scientific expeditions since 1904 and members have been the first to reach the North Pole, South Pole, climb Mt. Everest, descend into the Mariana Trench, and walk on the moon, to name just some small firsts. You could say I’m very excited to be included in that cadre. There are many famous expedition artifacts, books, and art as well as taxidermized animals lining the club walls but the first item that sticks out to me is Roy Chapman Andrews’s whip from his dinosaur egg expedition to the Gobi Desert. Roy Chapman Andrews was a famous explorer and was the inspiration for Indiana Jones, but before his more famous adventures, he was invited as the naturalist on an expedition to the Alaskan Arctic to collect a Bowhead whale. The expedition ship he sailed on was the Adventuress and she was built in 1913 in East Boothbay, Maine. She is also still sailing to this day, and I’ve been lucky to be a deckhand and marine educator on board the ship in the Salish Sea for the last couple of years!

At the dinner, it is immediately apparent that all of us new scholars and interns have stumbled into something truly remarkable, a society of extraordinary ocean heroes and advocates. You can tell OWUSS has a strong legacy through the voluntary involvement of so many previous scholars and interns who are here to support the scholarship society and its future. I am honored and grateful to join such a community.

The following day I dress up and enjoy the final presentations from the 2022 interns and scholars. It is exciting to listen to everyone’s incredible stories and watch the scholar’s year-end films. Hailey gives a brilliant recap of her time with the NPS, and it is difficult to not get even more excited for the upcoming months.

Congratulations to the 2022 scholars and interns, well done, and to the 2023 scholars and interns I cannot wait to follow along on your upcoming experiences.

The awards weekend wraps up on Sunday and we immediately roll into events for Blue Generation. OWUSS scholars and interns join other young ocean stewards from all over the world with backgrounds ranging from shark research to marine policy.

We start out the week with a lecture from a UN senior legal officer about ocean governance. We talk about the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Treaty which sets up a procedure for the establishment of large-scale marine protected areas in the high seas. It was adopted by the UN in mid-June and is a big deal because until now, there has never been any international law governing the high seas. Throughout the week we also cover topics like ecotourism, successful grant writing, and the blue economy.

One of my favorite talks of the week is from Sylvia Earle and John Vermilye on the rights of nature and protecting the ocean through criminal law. Sylvia Earle talks about ecocide and changing our habits and ethics so that we prioritize ocean health which is undeniably linked to our own health and survival. Also, shifting the burden of proof so that instead of ocean supporters having to prove that protection is possible, industry supporters must prove that exploitation is environmentally safe, and the ecological impact is acceptable. She shares a powerful short film about deep sea mining, called Deep Trouble, which I highly recommend watching.

While we are having these positive discussions in the Explorer’s Club, outside New York is experiencing the worst air pollution in recorded history from wildfires in Canada in June. It is hard to wrap my head around how massive and out of control the issues seem to be. There are people out there who want to start tearing up the deep sea and we clearly have enough going on being in the middle of a climate catastrophe. What can I do to make a difference?

I’m privileged to have a choice and I am also here about to embark on an internship that will have me flying across the country, massively increasing my carbon footprint because of the number of flights I will be taking. Is it hypocritical to call myself an environmentalist and then take 15 flights over a few months? I feel conflicted and confused, but I think a good first step is acknowledging that my lifestyle choices have consequences. I will continue to critically reflect and keep searching for how I can best be a power for change.

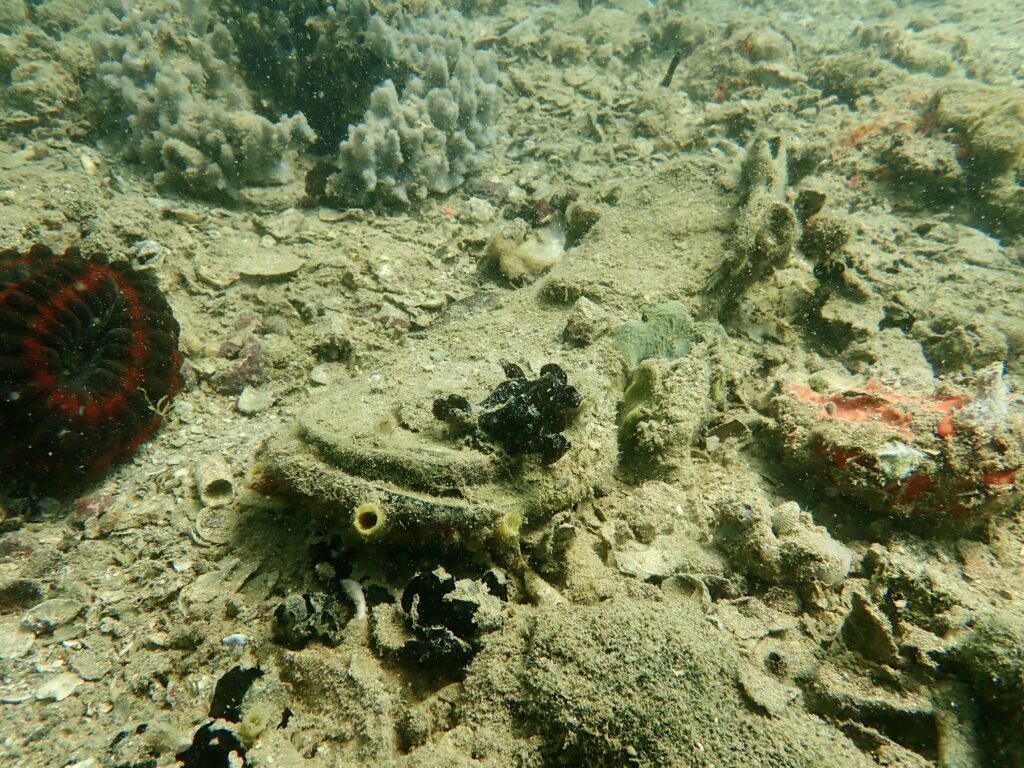

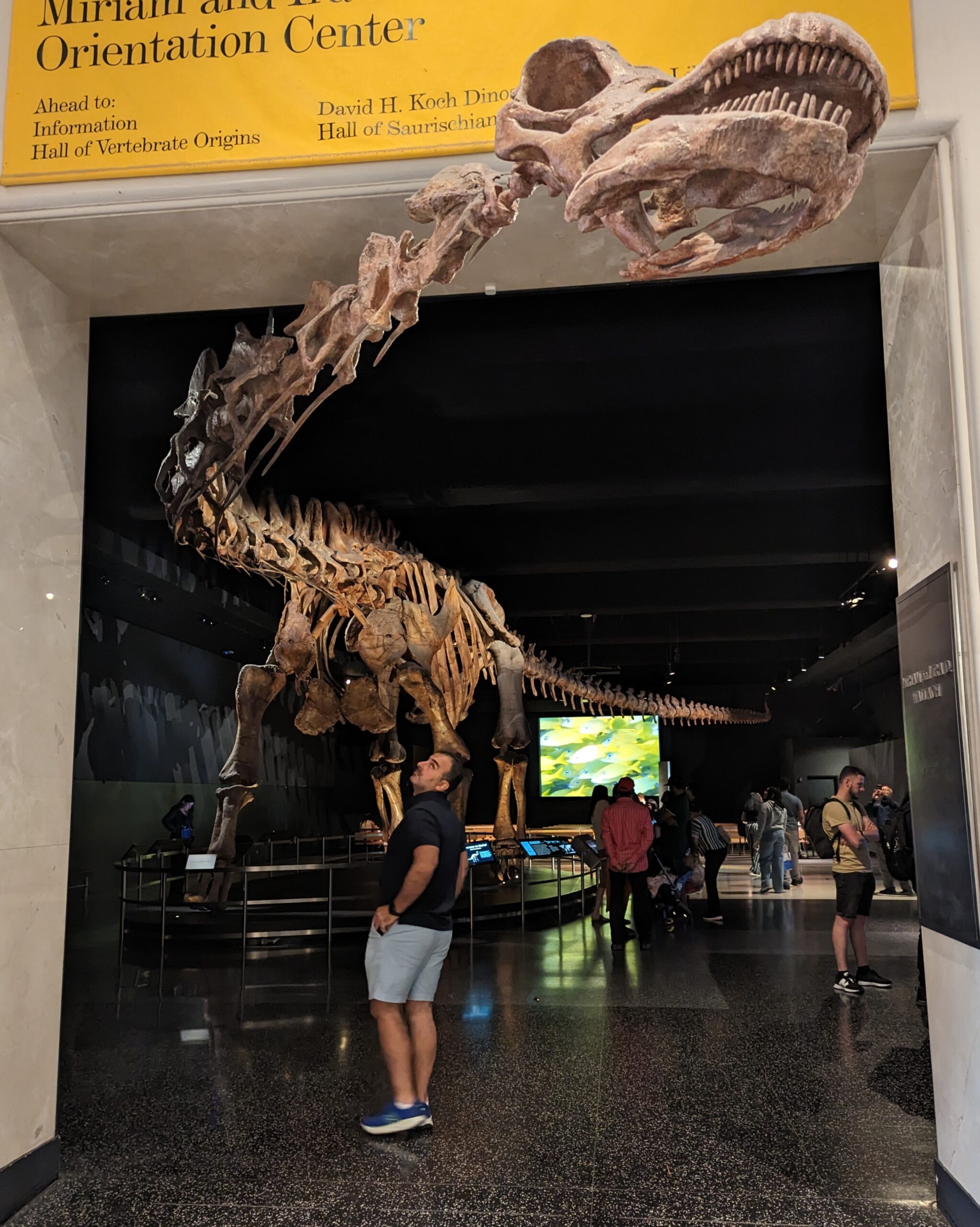

So many great memories this week with the Blue Generation; wandering the American Museum of Natural History, going on the field trip to ‘Rocking the Boat’ a youth empowerment non-profit organization building wooden boats in the Bronx, and going out in New York for some Salsa dancing. Thank you, Christina Janulis, for organizing the Blue Generation Oceans Week.

We finished off our Blue Generation week by attending the UN for World Oceans Day. That afternoon back at the Explorer’s Club I had a funny interaction. Out on the patio at the Explorer’s Club, Titouan Bernicot waved me over to say hi, and who did he happen to be talking to but Alex Honnold, the climbing icon, who was there to record a podcast. Alex introduced himself and I had to laugh a little. It felt like a wild dream to be hanging out with all sorts of legends this week.

It is a whirlwind of a week and I am sad to be leaving all of the incredible people and new friends as we go off on our separate adventures. I am hopeful for the future knowing they are all out there making a difference as ocean stewards.

I would like to thank OWUSS and the SRC for their support and a massive thank you to Claire Mullaney and Shaun Wolfe as my internship coordinators for starting me off on the right foot. Next stop, Colorado.

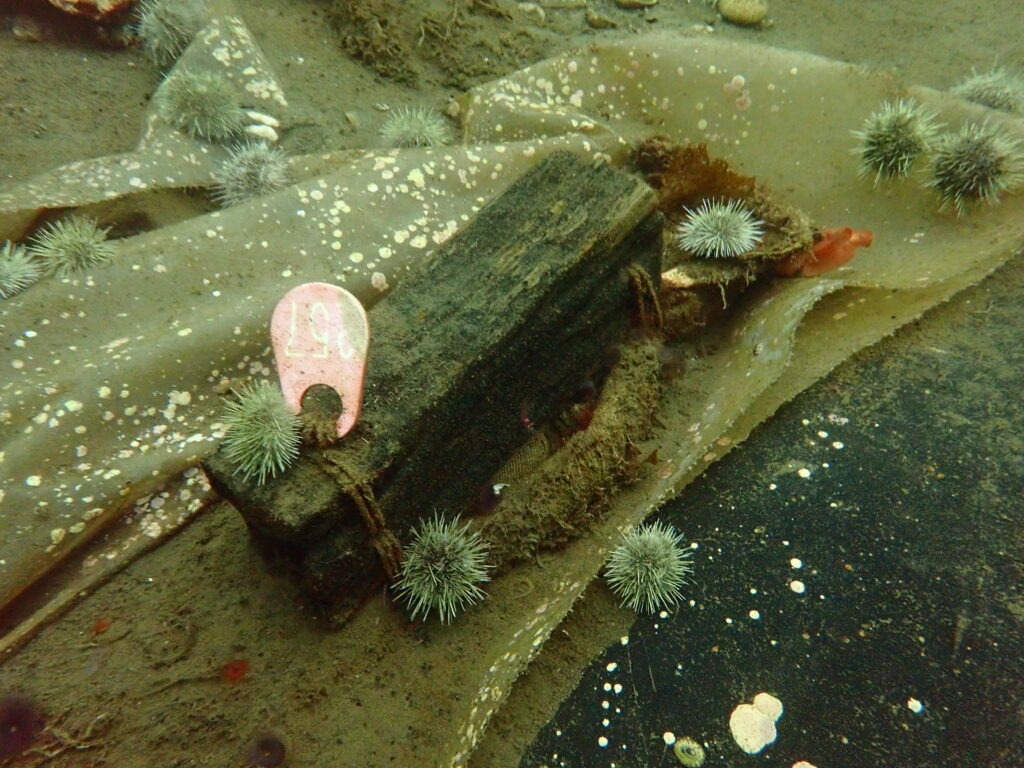

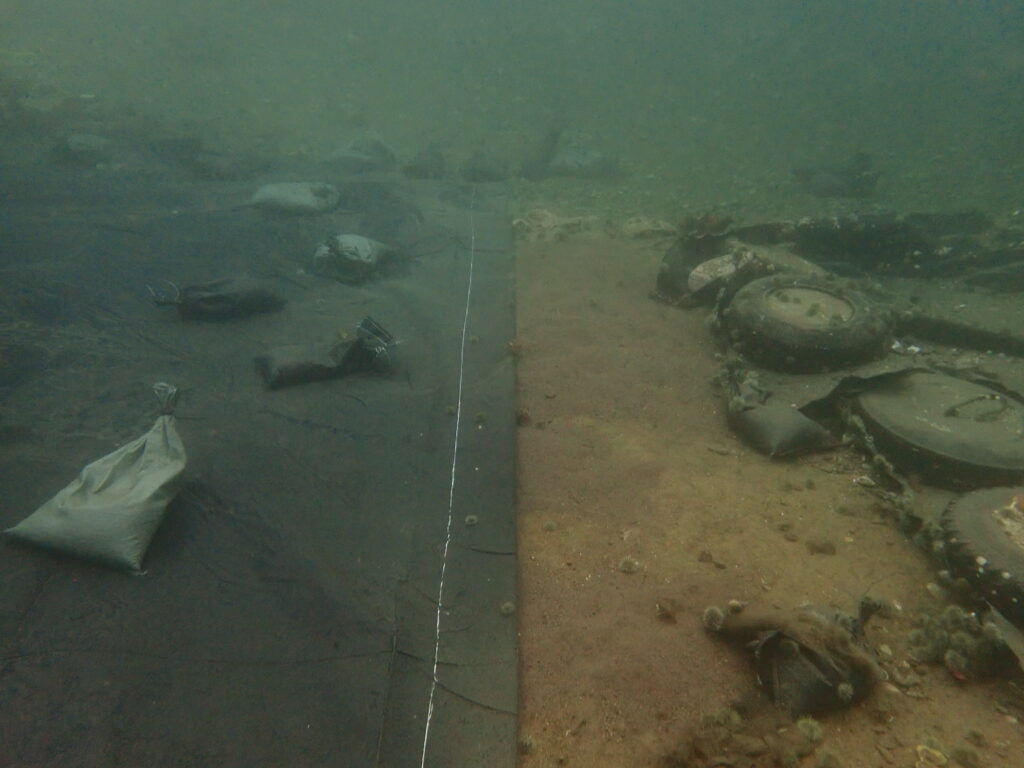

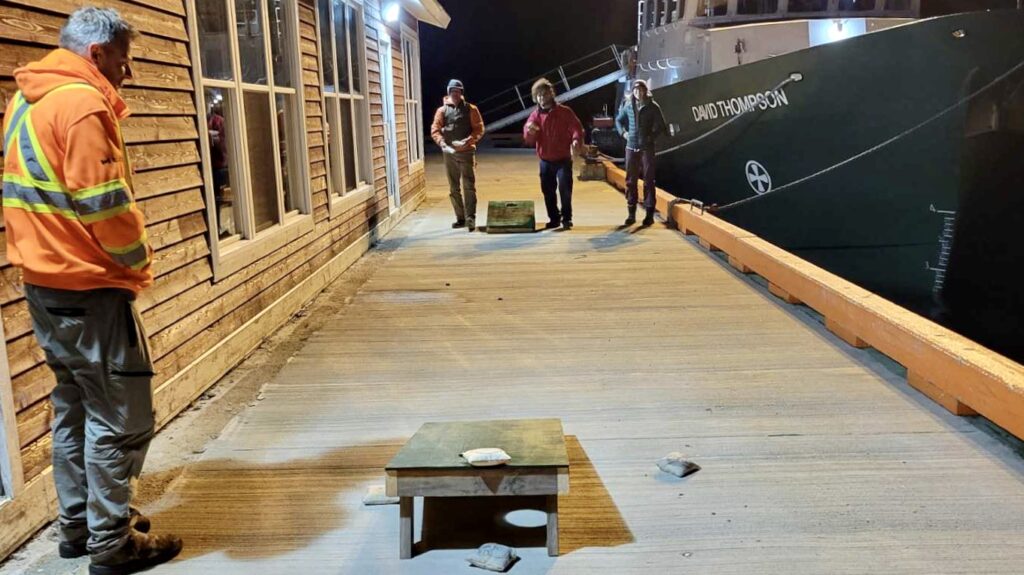

New tasks underwater require new tools, from crow bars and sandbags to steel bars and thick tarps

New tasks underwater require new tools, from crow bars and sandbags to steel bars and thick tarps