Isle Royale – Shipwrecks and Buoys in Lake Superior

Isle Royale National Park

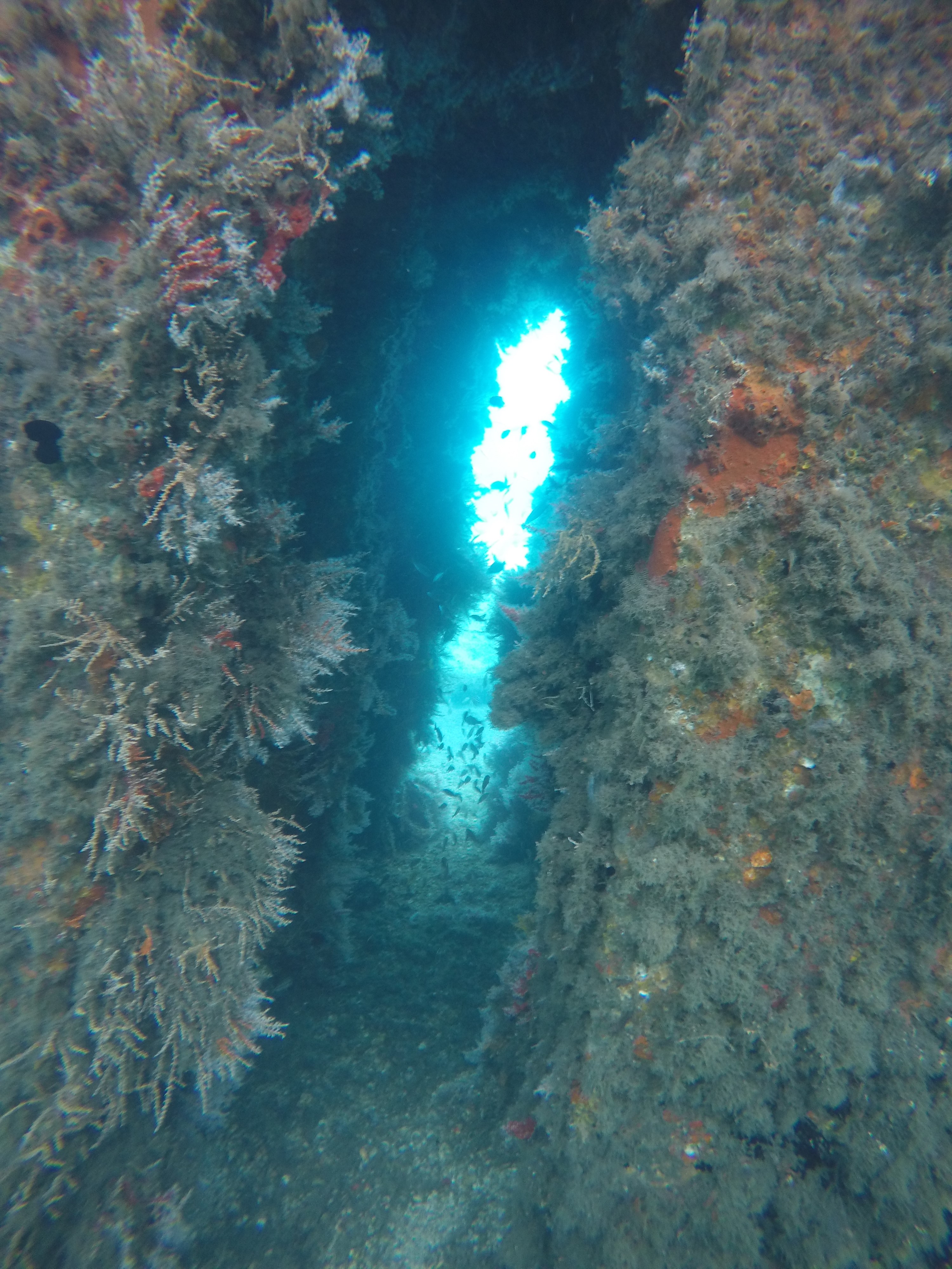

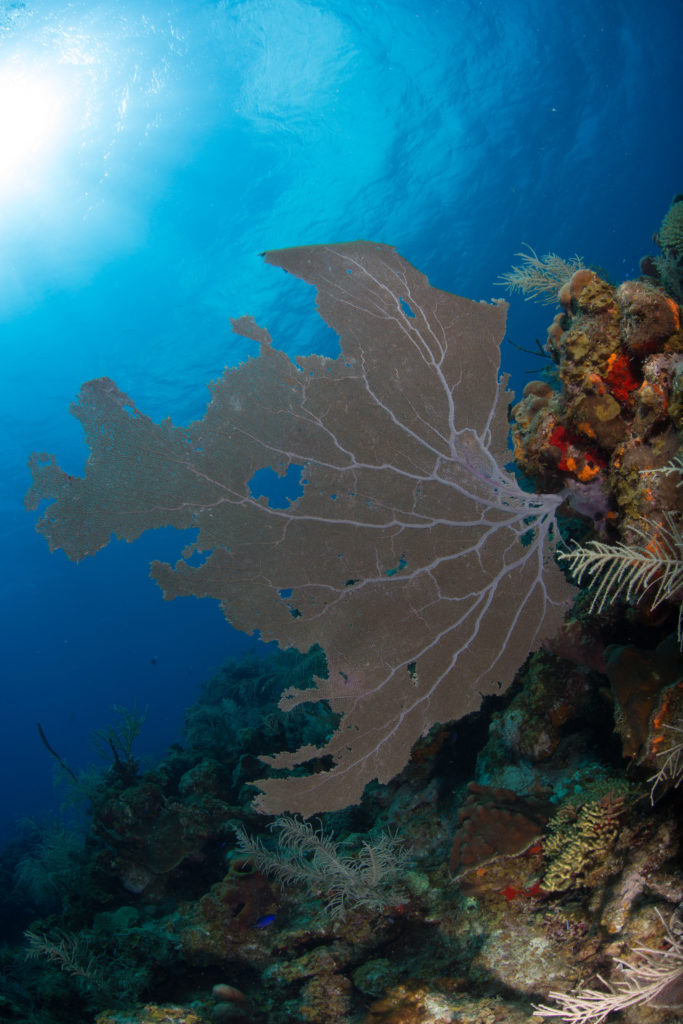

After the lengthy and fun-filled 18 hour drive we arrived at Grand Portage MI, our transfer point to the island. Isle Royale is an island in the Northwestern tip of Lake Superior, closer to our Canadian neighbors than Michigan. Made a National Park in 1940 to protect its wild landscape from the impact of the ever-interested logging and mining companies, Isle Royale is a remote and hard to access park boasting untainted northern wilderness, diverse wildlife, and beautiful backpacking. Its 893 square miles of woods host wildlife such as eagles, moose, and wolves. It is also home to the longest-running ecological studies of a predator prey system in the wild (61 years and counting), studying the oscillating population cycles of the island’s moose and wolves. For those of us more interested in the underwater side of things, it also is home to ten major shipwrecks – nicely preserved by the cold, fresh water and free of fouling by invasive zebra mussels. These wrecks, concentrated around the island due to its precipitous bathymetry and centralized location in major shipping routes, are what brought us to this chilly and wild island paradise.

-

-

Calm day on the water

-

-

Nice and green out there

-

-

One of the island’s roughly 2000 moose

-

-

Lots of nice hiking on Isle Royale

Isle Royale is only accessible by boat or seaplane, and since we couldn’t fit our 2 tons of luggage into a small four passenger plane we opted to boat over. Upon arrival to the harbor we were met by West District Ranger Steve Martin, a close friend of the SRC who had arrived to welcome us to the park and help us across transferring project equipment to the island. Apparently things had been running far too smoothly at this point, because it was then that the SRC’s vessel, Cal Cummings, decided to protest our seamless morning with a myriad of boat-complaints – from battery to steering issues. I was impressed with the SRC’s troubleshooting and repair skills, after a bit of time at work they were easily able to locate the problem and coax the vessel back into service.

Launching the Cal Cummings, the SRC’s vessel

Not a bad day on Lake Superior

While our boat was undergoing a quick attitude readjustment, I joined the first trip across to the island on one of the ISRO boats. My first time on the waters of Lake Superior was stunningly beautiful- sunny, calm, and warm. Reading about the Park and the lake itself, I expected to run into much less favorable weather. Stories of intense storms whipping up 30 ft swells and winter chills dropping far below zero had me prepared for the worst, but my introduction to the park was beautiful and favorable. Zipping through the calm protected waters of Washington harbor and watching small wooded islands and the outstretched fingers of the elongated Isle Royale fly past was thrilling, and heavily reminiscent of the protected inland seas of Southeast Alaska.

-

-

Lots to load – roughly half the gear for the trip waiting to be put on a vessel

-

-

Full deck – shuttling the gear across to the island took two full boatloads

-

-

Remnants of snow on the banks served as a reminder of the harsh winters that envelop this remote land

After an hour crossing, we arrived at Windigo, our home for the next 3 weeks. Located at the western end of ISRO and consisting of a visitor center, store, campsite, and housing for park employees and visiting researchers, Windigo is the smaller of the two main entry points of the Park. While small, this is the only populated place for miles on this wild island and is a welcome stopping point for backpackers and day-trippers alike. Being a small operation, Windigo is home to one road and one car – an old Jeep that I’m not sure ever gets used, as it sat in the corner of a small field near the store the entire time I was there (and from what I hear, in the same exact spot it was in last year as well). Transportation of gear is handled mainly by a small fleet of miscellaneous vehicles: a golf cart, a utility vehicle, and a tractor hauling a small wooden trailer. The latter is what we used for our first couple trips hauling our bounty of gear up the hill to our housing, and quickly became an invaluable part of our daily pilgrimage to and from the dock. These vehicles are used and maintained by Marty Ogden, lead maintenance staff for the Windigo part of the island, who was incredibly helpful during our time on the island with everything from transportation, to maintaining power, to helping us unload all our gear.

-

-

Welcome to Windigo!

-

-

Views from the Windigo pier

-

-

Lots of gear part 2 – we took full advantage of the spacious housing provided to us

While the primary reason we came to ISRO was to conduct 3D photogrammetry (more on this later) for a couple of the area’s shipwrecks, we couldn’t jump right into the fun. First, we had some other work to do: helping out the ISRO dive team with installation and maintenance of some of their buoys. The Park uses many buoys, some to mark safe passage into harbors or submerged hazards, and others as moorings or markings of wrecks for dive operations. These buoys are instrumental in keeping visitors and passing boaters safe. Unfortunately, the waters of Lake Superior get very cold in the winters and often freeze over – requiring the buoys to be removed when the park closes for the season. This means that, come May when the Park begins to open back up, lots of buoys must be reinstalled. The SRC, as a way to repay ISRO for helping support their photogrammetric efforts, assisted in buoy installation according the strict manning requirements of OSHA for the first week of our visit. And so, we started our work.

SRC diver Matt Hanks splashes in for the first dive of the trip while Jim Nimz observes from the water

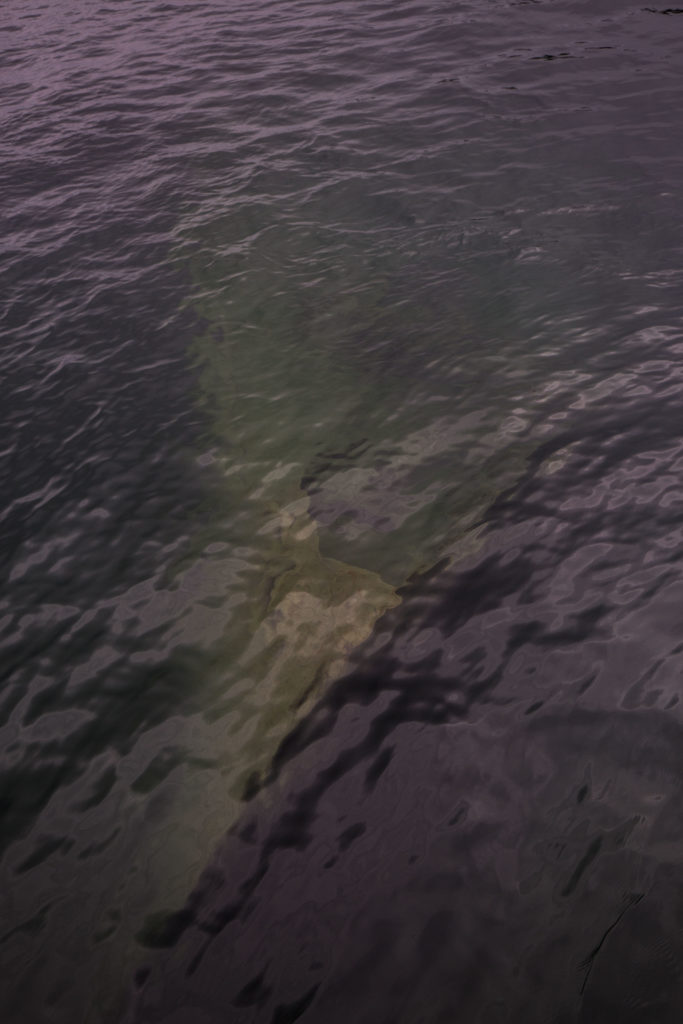

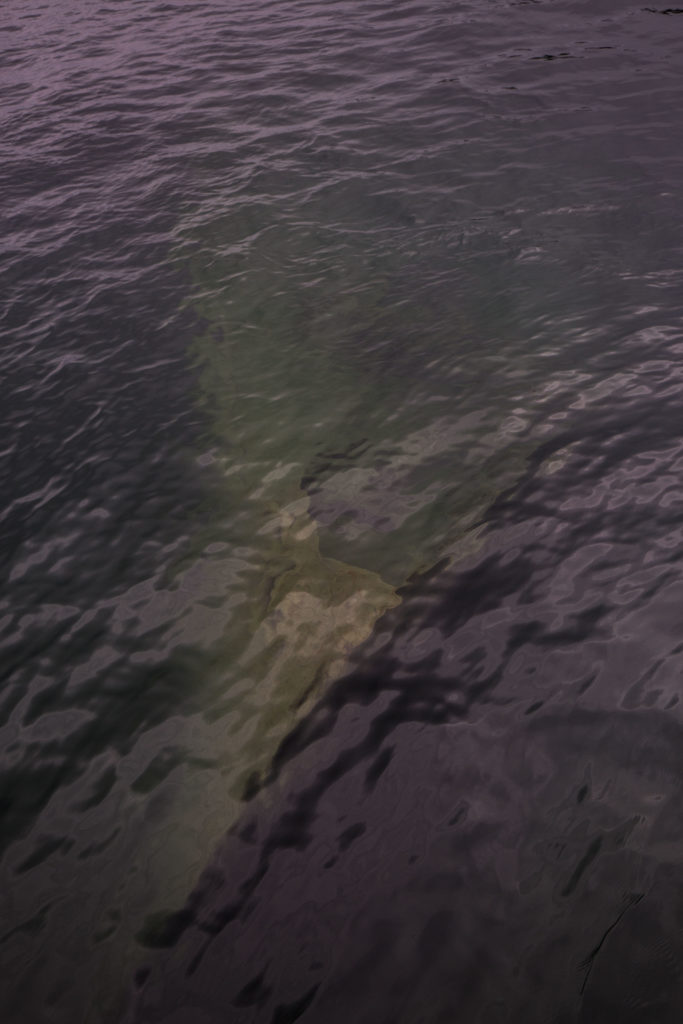

The first dive of the trip was on a sunken passenger ferry just barely inside the mouth of Washington Harbor, the America. This vessel, which lies in the protected waters and juts out of the depths to a mere five feet below the surface, was an easy way to start the trip as well as a good introduction for work to come – as the America was one of the primary photogrammetry targets of this trip. The work – which consisted of two divers locating the wreck and buoy attachment point (pretty easy when it’s visible from the surface), getting passed buoys from surface support on the boat (yours truly), and attaching the buoys via high-tech maintenance tools (wrench and zip ties) – went by without issues. I also got to see my very first wreck of the trip, one of the shallower ones at the bow and quite intact. Seeing glimpses of such a sharp and clean bow emerging from the depths from the deck of our boat was a powerful image for me, a small taste of what lies hidden in the foreboding waters surrounding this island.

-

-

Susanna Perkins waits on deck to pass of the buoy to the dive team

-

-

The bow of the America peeks out from the depths

Later that afternoon, I got in my first dive of the trip – my first in the Great Lakes and my second freshwater dive I’ve ever done – splashing in the comparatively balmy waters just off the Windigo pier (44 degrees compared to the 36 degree water just outside the harbor). Getting in the water was thrilling, seeing the lake floor carpeted with fallen leaves and branches from the nearby shore, the water dark with tannins. I delighted in the delicately silty bottom, and coming from a biological background, was excited to see some native clam species. As well as an introduction to the lake, the dive served as a check-out for me, where Brett observed and evaluated my skills. I guess he was sufficiently pleased, as shortly after I was cleared to join the team on some working dives.

Heading out for a day of work

Brett Seymour navigating to one of the sites near Rock of Ages lighthouse

The next couple days were a flurry of more maintenance diving. The team installed buoys on more wrecks (the Cox and the Chisolm) out near the Rock of Ages lighthouse, and then boated over to ISRO’s administrative headquarters, Mott Island. There we met Park Dive Officer Mike Ausema, Natural Resources Chief Seth DePasqual, and super volunteer Carol Linteau. From here, we would split the teams up to work on two different objectives. Team one (Mike, Seth, Brett, Susanna, and Matt) would go out on the ISRO park vessel and install a selection of harbor buoys, while team two (Carol, Jim, and myself) would stay back on land and work on some much needed buoy repairs to prepare them for install.

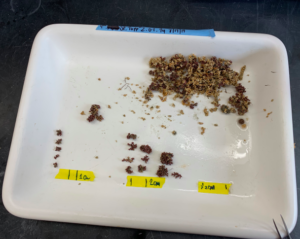

As part of team buoy maintenance, I got to learn some of the more technical, land-based aspects of the craft. Jim, maintenance diving expert and the SRC’s gear guru, is very knowledgeable in these regards and served as a bit of an instructor to Carol and I over the next couple hours. Under his patient direction, I learned a couple of skills essential for buoy work: splicing rope, mousing wire, and removing marking stickers. I was also able to master the art of efficient wrench-usage. With these newly acquired talents, I helped Jim and Carol prepare three new buoys for installation marking submerged wrecks.

ISRO Park Dive Officer Mike Ausema and ISRO Natural Resources Chief Seth DePasqual installing a no wake buoy. Image – Susanna Pershern.

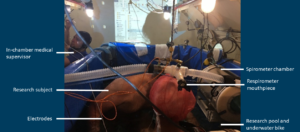

Throughout this first week I was able to learn a bit about the technical aspects of NPS maintenance diving. Unlike most types of NPS dives, which are classified as scientific dives, maintenance dives are considered commercial dives and are sanctioned under OSHA rules. This means that they must be done slightly differently: they cannot be conducted on closed circuit (the SRC’s preferred method of diving), divers must carry a bailout bottle, and there must be a dive tender geared up and waiting at the surface while the maintenance buddy team is down, ready to hop in and assist at a moments notice. It was cool seeing all this work get done in a different fashion – despite not having dove much with the SRC team at this point I knew how much they were into diving with rebreathers, as it makes for more efficient diving (DSO Steve Sellers told me that they had run the numbers and found that they were 40% more efficient diving in the field with closed vs open circuit) – and seeing the team do such varied work. While not necessarily as thrilling as conducting archaeological assessments or 3D modeling shipwreck sites, maintenance diving is an important part of the diving work done at ISRO and is invaluable in making the area safer for visiting boaters.

The SRC geared up and ready to go, maintenance-style (left to right): Matt Hanks as dive tender, Jim Nimz and Susanna Pershern as divers (complete with bailouts)

I guess I had been a good intern during my buoy repair times on Mott Island, as I soon got word of some exciting news. The next day we were traveling to the north shore of the island, where, along with some buoy installs, I was to be treated to my first wreck dive of the trip: a dive on a massive freighter that wrecked there in 1947, the Emperor.

Brett Seymour examines the windlass of the Emperor

The day started off exciting: as well as going to and diving off of the north shore, where some of the islands deepest and most exciting wrecks lie, we were going to make a quick stop at the uninhabited ranger station on Amygdaloid Island to pick up a buoy and change into drysuits. Upon arrival at the small fringe island we were met with a bitter cold wind that felt like it had just came from the Canadian arctic, whipping through the chilly forests and across the border and the small stretch of water that separates Amygdaloid Island from the Canadian coast. Biting and unrelenting, the wind made a compelling argument to put on every warm layer I had and cover it all in a big waterproof suit. Thankfully an old ranger cabin on the island was available for our changing needs, and in its rustic and unheated wooden walls I climbed into enough layers to clothe a small family: three thermal bottoms, five thermal tops, two pairs of wool socks, and two drysuits one-piece undergarments, stacked on top of each other. With my newfound warmth and lessened mobility, I joined the team on our boat as we left that rugged and icy island in search of shipwrecks. The day was already off to a good start.

The cozy ranger station on Amygdaloid Island

As we traveled up towards our site, with the Canadian coast off our port side and Isle Royale’s north shore, speckled with remnants of the winter snowbanks, I thought of what it would be like going down in these waters. Many of the island’s shipwrecks met their watery grave during the lake’s violent winters, where storms thrashed the vessels into shoals and pulled passengers under. Wrecking here during the harsh northern winters was almost a sure death sentence – if the waters didn’t get you, the air would. One of the wrecks we passed on our way up that day, Kamloops, is a testament to this. The ship, now resting at a depth of around 260 ft, wrecked during a violent winter storm in 1927. While some of the passengers went down with the ship (and some remain there to this day), many escaped and made it to shore. These unlucky people didn’t fare much better than their drowned companions – the brutally cold temperatures quickly took their toll and the initial survivors succumbed to the elements. The fate of the Kamloops long remained a mystery – the ship vanished during a winter with no trace of its whereabouts until the discoveries of the bodies of some of the crew the next year along the coast of Isle Royale, and even then the location of the vessel itself was still unknown. It wasn’t until 50 years later that it was discovered by a diver.

Imagine being stranded on a remote coastline like this, during a winter storm with freezing temperatures and blustering winds

The fate of the Emperor, however, shows that storms aren’t the only cause wreckage around Isle Royale. The Emperor, a 525 ft freighter traveling along a common trade route across the lake, hit a barely submerged shoal off of the island’s north shore on a calm and moonlit night around 4AM on June 4th, 1947. Speculation says that an inexperienced first mate may have improperly adjusted the course by a couple degrees, dooming the vessel and setting it on a course for the reef. Reefs like these surround the island, and have caused the end of many of the ships that now rest beneath the surface.

-

-

Exploring the wreckage of the Emperor

-

-

Big ships need big anchors

-

-

Lots to see amongst the scattered wreckage

After arriving at the site of the bow of the Emperor, our first team of maintenance divers went down to attach our freshly spliced and stickered buoy. After a successful attachment, it was time for my official introduction to Isle Royale diving. Brett hopped in the water with me and we dropped down to the massive bow of this unfortunate freighter. The size of this ship was hard to grasp at first – despite being relatively intact, years of ice forming and breaking on the surface of the lake has taken it’s toll on the comparatively shallow (40-50ft) bow and has left it partially mangled. Regardless, the wreck was still in great shape and very imposing, with massive features like a huge windlass, deck winches, and anchors present for viewing. Brett took me around the to the good spots and then ended the dive with a quick buoy inspection (have to make sure the team is doing quality work). Being the elite dive team that they are, they passed with flying colors.

-

-

Brett Seymour examines the team’s handiwork

-

-

Everything checks out – the Deputy Chief is pleased

The rest of the week was filled with more maintenance diving – attaching buoys to new wrecks, and fixing some older buoys that needed more chain due to lake level rise from last seasons massive precipitation. Maintenance teams went out to add buoys to three more wrecks: the Cox, the Chisolm, and the Glenlyon. Two of Isle Royale’s dive team, Seth and Carol, came down to join in on the festivities for these installs.

-

-

Retrieving a buoy to prepare for an installation

-

-

Buoy swap in progress

-

-

Removing the old buoy

Dusk in Washington Harbor, from a nice hike

Not being an experienced maintenance diver myself, I didn’t get in on too much of this fun but instead had a couple days off, where I was able to go on a hike and catch up on some work. I was able to get in a dive on the America with Matt, just to explore the site before we approached doing photogrammetry on it. An absolutely wonderful wreck, the America is an old passenger ferry that lies in 15-85 ft of water. It is very digestible, large enough to be exciting but small enough to swim around it in one dive. It also remains very intact, with the entire hull and most of the deck machinery in place still. It had recently (within the last 10 years) fallen victim to a large swell (or set of large swells) that did some serious damage to the cabin and rest of the deck structure, which made for a very interesting debris field off one side of the wreck. Overall a very nice dive site with lots to explore.

-

-

Matt Hanks on the stern of the America

-

-

Scattered wreckage on the America

-

-

Exploring the bow of the America

-

-

Matt Hanks at the bow of the America

-

-

The America looking spooky at depth

Interspersed in with all of the buoy work was the first test of the SeaArray, the SRC’s flagship photogrammetry machine. This incredible piece of equipment was put to the test on a break between buoy installs on ships – but I’ll save all that exciting stuff for the next blog. Don’t want to get ahead of myself. Overall, the maintenance and buoy work was very successful. Combined, the SRC and ISRO dive teams installed 11 buoys: 5 no wake buoys, 1 channel buoy, and 5 wreck buoys. These buoys will serve their important job keeping the waterways marked and safe for the rest of the season, until their removal before winter and the damaging surface ice comes. Now, with all the maintenance work done, we were free to get on to the exciting part of the trip: the 3D photogrammetry of some of Isle Royale’s beautiful shipwrecks.