For the first 15 feet of our descent, the cloudy green water only allowed views of up to 10 feet ahead – I was limited to watching the tank and bubbles of Matt Hanks, my dive buddy, as we descended on the stern of the George M. Cox. Upon reaching the bottom, the visibility opened up to a dark and slightly murky 30 feet, giving me my first look at my third wreck of the trip. Not as intact as the Emperor or the America, the Cox was a bit more scattered and broken apart, but not without clear features. Some of the most striking ones sit right in the center of the wreck: two huge hulking boilers, nearly 10 feet in diameter and 20 feet long. These were stark, imposing, and an instant attention-grabber – I knew they’d make for a nice photo. Eager to start photographing, I swam back, peered through my viewfinder, and started looking for a good composition. While shooting, I noticed a mechanical whirring noise. Rather quiet, slightly inconspicuous, but present – and slowly getting louder. Occupied with my boiler photos, I pushed it to the back of my mind – probably just something on our boat up on the surface – and went back to work with the camera. After thirty seconds or so, I look up from my camera to do a typical surroundings check, to make sure my buddy is alright and that nothing has changed drastically. Check was going great: buddy was fine, I was still at the same depth and location that I’d been at, wreck is all still here, and – suddenly I realized the source of the mysterious noise. Seemingly materializing out of the murk and barreling towards me at what felt like breakneck speed was a dauntingly large, sleek, blue DPV-powered sled with three cameras attached and a rebreathing diver being towed from the back, a veritable underwater UFO. I sprint-swam out of the way and looked up to see the 6-inch eye of a camera lens peering down at me as it passed just feet over my head. That was my first experience with the SeaArray, the SRC’s flagship photogrammetry machine, and we were now on to our next part of our trip to Isle Royale National Park: doing 3D photogrammetry on some of the Park’s giant shipwrecks.

3D photogrammetry is the process of creating 3D models of objects using still photos or video footage. This has a wide variety of applications, from visual effects to meteorology. It also turns out to be very useful in archaeology, the SRC’s original pursuit, as it allows archaeologists to have photo-realistic models of artifacts that may not be able to be removed from site (for cultural, diagnostic, or other reasons). It also has the potential to be indispensable in modeling larger, more inaccessible features like immovable objects, entire sites, or things that are difficult to observe and work on for extended periods of time – like submerged shipwrecks. The traditional approach to modeling shipwrecks was an endeavor: archaeologists would spend weeks on sites, putting in hours underwater painstakingly measuring and sketching these large-scale features. This process, something that the SRC perfected back in the early days, works perfectly fine but is a very time-consuming and effort-intensive process. Even back then in the 1980’s, photogrammetry was considered but not pursued due to insufficient technology. Now, in 2019, the SRC is finally putting the process to work on large-scale wrecks.

- Sketch of the Glenlyon’s triple expansion engine from the SRC’s original report on the shipwrecks of Isle Royale

- Rough render of an early model of the same engine in the previous photo – notice the details available in this model, created with hours of photogrammetry versus days of sketching

The tool for this project is a multi-camera array that has been the brainchild of Brett Seymour from the SRC and Evan Kovacs from Marine Imaging Technologies. Brett and Evan have been close friends for a while and have combined their friendships and affiliations on many projects in the past – filming, photographing, and 3D modeling wonders of marine archaeology from WW2 plane wrecks to Ancient Greek shipwrecks. They’ve been working together on the SeaArray for several years now, testing and perfecting it through various iterations. The most recent version, the one that I was lucky enough to see and dive with, consists of three 45.7 MP cameras (Nikon Z7s) in custom-built housings linked to a center control console with HDMI feedback from the three auxiliary units. This whole array, which is held together with a custom-fabricated carbon-fiber system of tubes and pieces, is then linked to a DPV (diver propulsion vehicle, or scooter) for ease of movement (as lugging this huge piece of equipment through the water would be nearly impossible in a slight current). When in operation, this unit will fire off three photos at once (one from each camera) in quick bursts, collecting all the visual data needed to create a high-quality 3D model.

Now, why bother with making 3D models of these wrecks? I mean, it’s undoubtedly cool, but what does it do for us? From an archaeological standpoint, the technology of 3D photogrammetry is an absolute goldmine. The ability to make photorealistic scaled models of sites and artifacts with relative ease is valuable in general, and especially when it comes to marine archaeology as every minute spent underwater is more complicated, expensive, and dangerous than those spent above the surface. Being able to have an accurate model to examine from the safety of a desk anywhere in the world is far more convenient than having to travel to and dip underwater to see. Alongside ease of studying, having accurate models like these also creates a type of digital conservation, preserving the wrecks in their present state for years to come. While cold freshwater is an ideal environment for slowing decomposition of materials, ice and strong winter storms can still damage them – within the past 10 years, the America lost a large section of its remaining structure from some heavy swell. Had there been a model created before the incident, the wreck would have been preserved in its pristine condition indefinitely in digital form, allowing future visitors to experience it as well.

- Matt Hanks examining the prop of the Cox

Moving past the archaeological view, modeling wrecks like these is an invaluable tool for outreach as well. While photos, drawings, and videos of wrecks are captivating in their own way, there isn’t anything as immersive as a model that a user is able to explore on their own. It’s an incredibly useful way for visitors who may not be able to dive be able to explore what exists under the surface in their parks. The SRC does a great job of working to share this information with the public and have been producing great story maps (https://nps.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=1a72876ce6e24a74a732a80875ed33bf) to help share the story of the Isle Royale wrecks with the world. After all these wrecks, like National Parks, are public property – the Parks Service works to preserve and protect them, and to share their beauty with the world.

- Section of deck railing from the wreck of the Cox

- The remains of a luggage cart, mixed in with scattered debris

While an earlier version of this system had been tested in Isle Royale the previous year proving its effectiveness, it was now time to put the new model to work. The first wreck to experience the photographic power of the SeaArray was the George M Cox, one which had recently been dove by the team to install a new buoy. For the first test, Brett was the pilot with Jim Nimz as his buddy, while Matt and I dove around the wreck ourselves. After sending in team one and gently lowering down the array itself (Brett has been stressing its durability as an important factor in its design, but it’s still a little unnerving to not be careful when dropping a 100 thousand dollar camera system into the water), Matt and I geared up ourselves and dropped in. The dive went well, apart from having me having a near collision with the array itself, and we were now ready to put it to work on the two wrecks that we had planned to model this trip: the America and the Glenlyon.

The next couple days were dedicated to modeling the wreck of one of our two primary objectives this trip, the Glenlyon. A steel steamer sunk in 1924, the Glenlyon’s wreckage is scattered over two areas on either side of the shallow shoal that brought it down. With the stern on one side and the bow on the other, this makes for quite a bit of area to cover when modelling. Furthermore, the SRC wanted to link the two areas into one cohesive model by covering some of the shoal in between the two spots, making this site a multi-day project. To make things even more difficult, the site was about a two-hour boat ride away from our home base at Windigo, on the exposed southern coastline of Isle Royale.

- One of the Glenlyon’s large boilers

- Scattered debris covered most of the lake floor of the site

- The plunging slope of the Glenlyon shoal itself, the one that brought the steamer to rest

- The prop and drive shaft

For my first day on the wreck, the mapping objective was the wreckage scatter of the bow of the ship. Brett and Jim were going in as the array operator and buddy, while I dove with Susanna Pershern. Our objectives were to photographically document the 3D modeling in action, as well as to avoid any possible collisions with the array itself (this one was more specifically towards me). The first dive on the wreck was amazing, another completely new experience. Like the Cox, this wreck was very disarticulated but still featured large recognizable items. The lake bottom was blanketed in algae-covered sheets of metal, interspersed with pieces like large gears or davits. The main features on the bow were a large boiler and then the mostly intact tip of the bow itself – complete with an anchor windlass still laced with the anchor-laden chain.

- The bow of Glenlyon, one of the most intact parts of the ship

- Detail on the anchor windlass

- The mechanical wonder of a triple expansion engine – check out those pistons

The next day we spent on the stern, a rather small site but one with some visually striking features. This spot, about an eight-minute swim away from the wreckage of the bow, is the final resting place of a mechanically-complex triple expansion engine – now a submerged mismatch of pistons, pulleys, and gears. Connected to this huge engine, and responsible for propelling this sunken 328-foot steamer, is a huge driveshaft and equally large prop. Altogether, this wreckage makes for a very cool looking spot, and stands to make a crucial contribution to the 3D model. In addition to the 3D photogrammetry, this site was going to be the location for one of Evan Kovac’s many other underwater cinematic pursuits: 8k 360-degree virtual reality video with the Hydrus, one of the worlds most advanced underwater virtual reality video systems. Having this much photographic power underwater in one location was a huge venture, one that took two vessels and eight people to manage but was really incredible to view.

While spending hours underwater taking hundreds of gigabytes of photos and videos a day may seem like enough work to occupy a team, it just doesn’t cut it for the SRC. After returning from a day of diving with the SeaArray collecting photogrammetric data, another type of work begins – photographic processing and the creation of the 3D models. This workload is so intense that the SRC brought in a ringer just to work on it – Bryce Sprecher, a recent graduate from University of Wisconsin, Madison, and an absolute photogrammetry whiz. As well as bringing his expertise in photogrammetric processing, Bryce also brought along a custom built top-of-the-line computer, funded by Marine Imagine Technology specifically for this work. This computing beast was created to attempt to cut down on the lengthy processing times of creating these 3D models, which can range from 8 hours for a low-quality model to upwards of a week with higher quality ones. Bryce, Brett, and Evan worked together each evening to process and turn the roughly one terabyte of data created in one photogrammetric dive into a viewable 3D model, sometimes staying up into the late hours of the night – there’s no rest when you’re out in the field.

All that hard work is worth it when it pumps out sweet models like this – this is a model of the engine of the Henry Chisholm wreck created the last time the SRC visited Isle Royale

While the photogrammetry data was whipped up into some low quality models while out in the field (low quality was used to get a quick view of the model to determine that sufficient photographic coverage was acquired), the VR data had to wait to be turned into a polished final product. Talking to Evan, I learned that it’s quite the process to turn the super wide-angle footage from the 10 cinema-quality cameras into one seamless and professional 360-degree video file – one that can run up to 20 thousand dollars to process and produce a three-minute clip. That stuff would have to wait. For now, the focus was to be centered on getting out rough 3D models to confirm enough photographic coverage of each site, allowing us to avoid a situation where gaps in data are realized once we’ve left. This strategy saved us a couple times as well – early renders on the Glenlyon showed the team bare patches in the model between the main wreck and scattered wreckage, but still alerted us early enough in the trip that we had time to return to the site and fix the issue.

- The America in its prime. Photo: Kenneth E. Thro Collection, ISRO Archives

- The America on its way out. Photo: Wolbrink Collection, ISRO Archives.

Along with the Glenlyon, the other modelling target for the trip was the America. Sunk just inside the mouth of the calm Washington harbor, the America was slated to be an easy grab – protected from swells in almost every situation, a short 10-minute boat ride from the harbor, and not too deep to require advanced dive planning. There was only one issue: the wreck lay on a steep slope, making it highly variable in depth with the bow at around 2 feet deep and the stern reaching 85 feet. This leads to a huge gradient in lighting on the ship, which creates problems for imaging. How do you get even exposures when you’re transitioning from shooting in near daylight just below the surface to the gloomy depths of 80 feet underwater murky lake water? You shoot it at night.

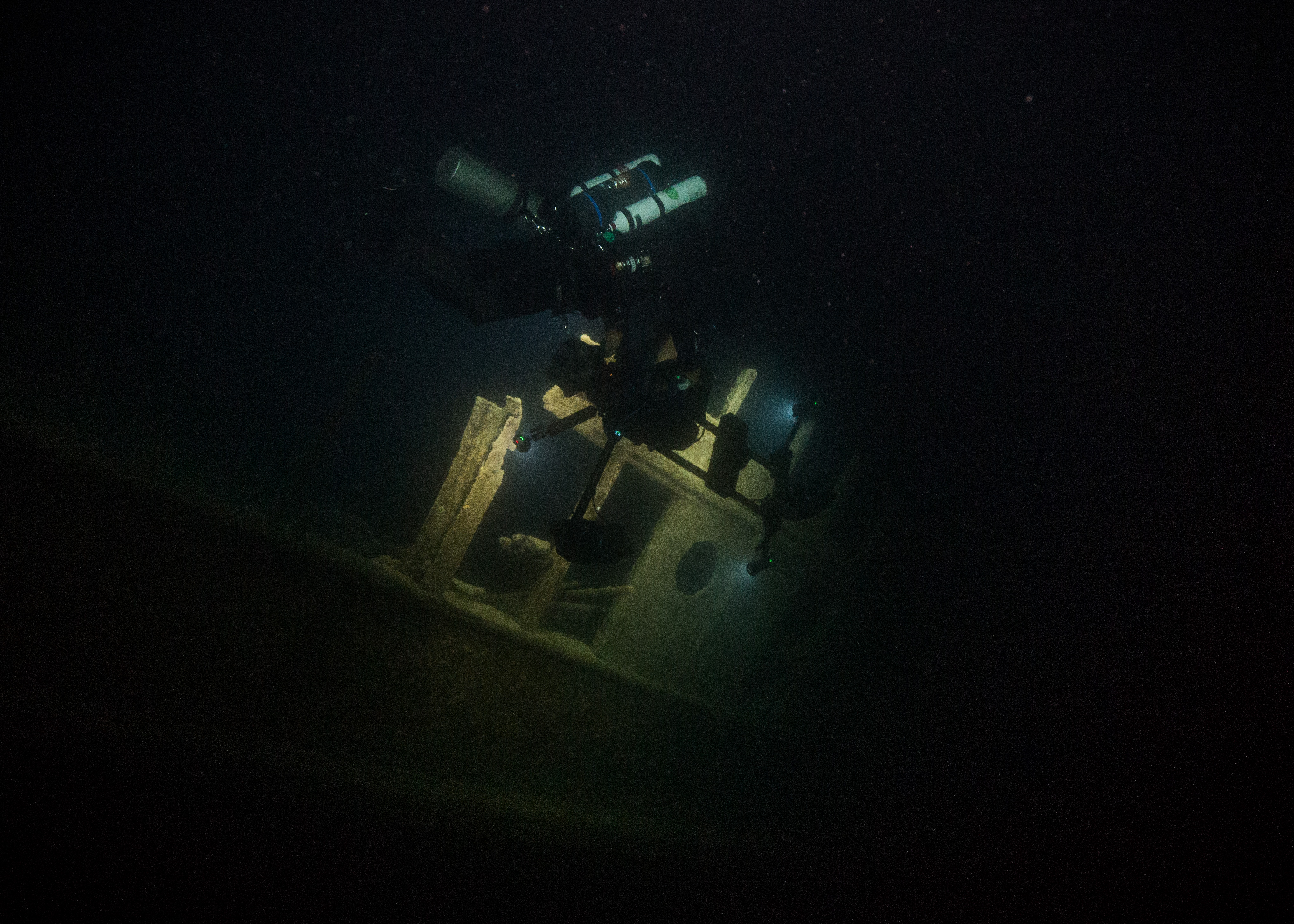

The wreck of the America with the SeaArray over the bow, backlit by divers. Photo by Bryce Sprecher.

Now, this solution didn’t solve all the potential problems with modeling this wreck. There was still the huge change in depth, which created buoyancy woes when weaving up from 80 feet to the surface and back down again, over and over and over (especially when diving a closed-circuit rebreather). It also created new issues that had to be dealt with. The SeaArray now needed lights, and ones powerful enough to illuminate a large enough swath of ship to create an even exposure in all three of the cameras wide field-of-views. We also needed to mobilize a team to go out at night, needing more surface support and a larger staging vessel to make sure everything stays safe. Finally, you have the ever-present issue of temperature – the 37 degree water feels cold enough in the daytime.

Lots of factors were at play to make this wreck difficult to model, but at the same time there were lots at work to make it worth it. The America is arguably the Park’s most popular wreck due to its intactness and ease of access, raking in a good 20% of the yearly dives done at Isle Royale. It’s the only wreck that is accessible to non-divers as it’s bow nearly peeks out of the water and allows for a good section of the wreck to be seen from the surface. It also holds a special place in Park history: the vessel served as a passenger and cargo ferry for Isle Royale for a good 12 years before her untimely demise. Finally, it’s a visually striking wreck, and one that’s potentially structurally unsound as well (a portion of it collapsed in recent years), making for a good argument towards preserving it digitally with a 3D model.

The stern of the America, which up until recently was the home to an intact wheelhouse instead of the pile of timbers that you see here

So, with all this in mind, our team set off around 9:30 one evening (the sun doesn’t set until around 10, and we needed complete darkness) and motored off towards the America. It was a beautiful evening – warm, no wind, flat water – setting the stage for a seamless dive. After waiting for darkness to fall, we sent in the team of photogrammetry surveyors (Brett as the pilot and Evan as his buddy) and shortly after the photographers (myself and Susanna – a big thank you to Susanna for rallying and joining me on this dark and chilly dive, I appreciate your sacrifice). As predicted, the dive was not without issues. Shortly before dropping I realized that both of my strobes refused to work (despite battery changes and gentle encouragement) and immediately after descending realized that the seal of my dry glove had a major leak. This meant that all I had for illumination and navigation was the heavy-duty video light that I had on my camera – not ideal. To make things worse there was a slight current, which can be very disorienting when you’re dealing with a near blackout dive on a confusingly oriented surface like the heavily slanted deck of the tilted America. However, all of this frustration vanished with I got my first view of the Sea Array at night: Strapped to the gills with four 15000 lumen video lights and slowly motoring up the side of the wreck from the depths, it somehow looked even more alien than it had the first time I saw it. Susanna and I only stayed down for a little over 20 minutes until the extreme cold (and completely soaked left arm in my case) forced us to evacuate the water, but I absolutely loved those 20 minutes that I got to spend watching that marvelous creation weave slowly up and down that gloomy wreck at night.

The rest of the trip was occupied with getting the last little bit of data needed on the Glenlyon, as well as filming some VR video with Evan’s Hydrus on the wrecks of the Emperor and the Cox. After completing all our scheduled work, we started up the busy process of packing up our many boxes of gear and heading on to our next ventures – which, for me, was the sunny beaches of the St. Croix in the US Virgin Islands.

This seems to have been an exceptional project really pushing boundaries of underwater imagery. Also, very well written by Michael Langhans.

It is great to see the national parks still the focus of such pioneer efforts in underwater documentation. Brett Seymour and Evan Covox are indeed tenacious problem solvers. I am also impressed with the writing style of Michael Langhans who has conveyed the important details of a highly complicated research operation in such an accessible way.

Thanks Dan! It’s an honor to hear that coming from a legend like you – big fan of your work! I feel very lucky to have been able to be involved in a project like this, especially one centered in such an incredible place. And yes, Brett and Evan are quite the team! They were great to work with.

Nice work! Great to see the progression of the technology and the improvements being put to use. Dive safe!

Thanks for your kind words Kelly! Appreciate the support!

Stunning! I was the NPS Superintendent of Isle Royale National Park from 1975 to 1980 and was instrumental in getting SRC (then SCRU) involved in the first official survey of Isle Royale’s shipwrecks, and their eventual designation on the National Register of Historic Places. I have also personally dove on all the shipwrecks mentioned in the article. I can only marvel at the advances in technology that made this article possible. Fantastic photography, amazing diving, and wonderful writing. Thanks to all involved.

Jack Morehead