I’m back in Kalaupapa! My plan to head to the National Park of American Samoa after Kaloko fell through leaving me with an open schedule for the next week. Kelly Moore and Glauco Puig-Santana were kind enough to invite me back to the peninsula and join them for the yearly Pacific Island Inventory and Monitoring Network stream surveys in the easternmost valley of the park. Waikolu Stream is isolated, extremely beautiful, and relatively untouched. The entire watershed is protected within park boundaries, a critical habitat for some of Hawaii’s unique endemic freshwater species. Since 2009, the network has monitored fish, invertebrates, stream flow, and water quality in Waikolu. In 2021, scientists took this data to the state of Hawaii to prove that too much water was being diverted from the upper valley for agriculture on topside Molokai, resulting in a large section of the stream drying out in the summer. The state eventually approved new instream flow standards to return water back to Waikolu and sustain the stream’s endemic biodiversity. Pretty cool to see data collected by the park inform management and ultimately conservation. I am very excited to join the survey team, do some backcountry camping, and work in a freshwater habitat.

The team is made up of Kelly, Glauco, and two interns Addisen Antonucci and Noah Hunt who fly in from Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. We were also supposed to be joined by Anne Farahi, the lead aquatic biological technician who usually collects all the freshwater fish data. Unfortunately, she cannot make it, so we will continue with the surveys without any fish data this year. While Glauco organized most of the equipment already for our trip, we spend a day packaging up all the camping gear, food, survey instruments, and personal gear which we put in dry bags and coolers. We load all the gear into a cargo net that will be flown out to our campsite by helicopter.

Our hike out to Waikolu is only a mile along the beach, but it’s all on basalt cobble and boulders that tend to roll no matter how big they are. We are all wearing hard hats because we are walking right under a massive sea cliff that has consistent rockfalls. You can feel the energy of the ocean as it sucks the cobble off the beach with every outgoing wave.

The mouth of Waikolu is framed by tall sea cliffs on either side. We hop across the stream and set up camp in a nice flat spot tucked up against the headland. It is likely a built terrace from early settlers because, of course, native Hawaiians lived in this valley. We will see evidence of rock walls and terraces all the way up the valley. Long before the state was diverting freshwater from this stream, Native Hawaiians were diverting it for their taro patches. This was also the original source of fresh water for people sent to Kalaupapa. The community gets its water from another valley nowadays, but the old, rusted water pipes are still present running along the beach. At first glance, one would assume the valley is untouched but of course, people have been altering this area for as long as they have been here. It is still absolutely breathtaking, and I have to take a second every now and then just to look up and admire our surroundings. We set up camp and make sure to really stake everything down because the wind whips through here.

After we set up camp, we hike a short way up the stream to our first survey site. There are more than 15 sites from the mouth of the stream to about 3 miles up the valley. At each site, we are surveying hihiwai (snails), mapping stream habitat type, estimating substrate size, testing water quality, and measuring the flow of the stream.

We follow an overgrown trail, weaving our way through the jungle foliage, the sun streaming down through the canopy, and the deeply spined green cliffs peaking through. Glauco points out shampoo ginger and the white ginger flowers that we pick and suck on for a bit of nectar. He navigates us to the site with a GPS and then runs a 30m transect tape the length of the stream. The stream is small and gentle, usually only a foot or two deep. A volunteer taro has found a spot to live. I join Kelly to learn how we are going to be surveying the hihiwai. As soon as I dip my masked face underwater, I am taken aback by the number of creatures. The crystal clear, cold water is filled with colorful gobies, hihiwai, and prawns.

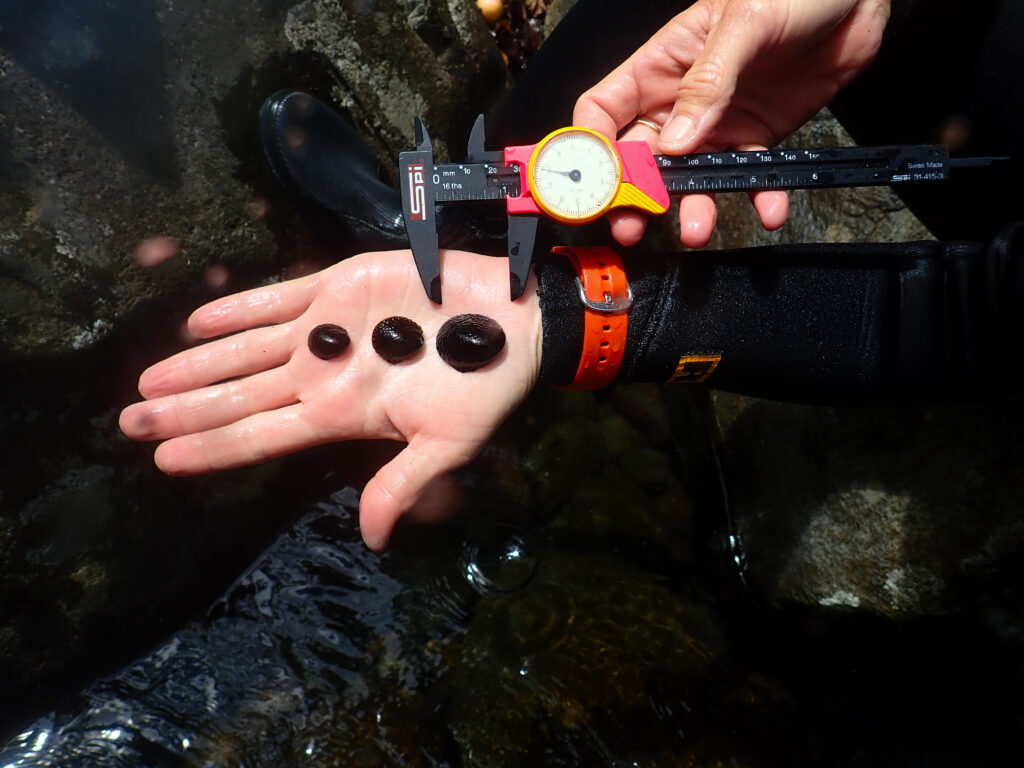

Kelly and I get to work ‘snailing’. To conduct these surveys, 10 spots are selected randomly along the entire 30 meters. At each spot, a 1/16m^2 quadrat is placed in the stream and Kelly with her mask and snorkel sticks her head underwater to find all of the hihiwai in the quadrat, pop them off the rocks, and hand them to me. I measure the diameter of the hihiwai with calipers and return them to a spot in the stream where they can reattach before getting swept away by the flow or eaten by a prawn. We measure all adults and count all spat in the quadrat and in an opposing quadrat we count all eggs. The eggs look like little sesame seeds attached to the rock. The hihiwai are endemic to Hawaiian streams and have really beautiful speckled shells.

After learning how to snail with Kelly, I join Addisen to learn how we estimate substrate size or what we call ‘pebbling’. At the beginning, the middle, and the end of the 30 m transect, we run another tape perpendicular across the stream, measure the width of the stream, and then divide to get 20 distinct equally spaced points. At each point, we will reach into the stream and measure the longest diameter of the rock under that point. It can be anything from a 5mm pebble to a 500cm boulder. As we pebble, we also use a densiometer to collect riparian canopy cover.

While snailing and pebbling are going on, Glauco is using a stream tracker to measure water velocity. He is looking for laminar flow to get accurate measurements. At some sites, we are also doing water quality, just like we did on the dive surveys. We have the sonde device that measures pH, salinity, dissolved oxygen, etc. and we also take water samples to be processed for dissolved nutrients later.

Back at camp Glauco makes rice and beans and veggies for dinner and we sit around in our camp chairs and enjoy the sunset. I sleep with my rainfly off because it’s beautiful and I’m hopeful it won’t rain. Well, I end up getting soaked and I scramble to get my rainfly on in the middle of the night when it starts to pour.

I get an exceptional view of the pali when I wake up and unzip my tent. I have coffee and oatmeal and load up for our daily hike up the valley. We bring our wetsuits, snorkel gear, felt-soled neoprene booties, flow-meter instruments, water quality testing gear, pebbling tools, and the three-pong sling if we have extra time to catch some invasive Tahitian prawns.

We follow the trail through the kukui tree grove, past the strawberry guava trees, the ginger fields, and the hao. The first two stream crossings I attempt to keep my feet dry. By the third, I have given up and accept that my shoes and feet will be wet all day.

We come upon a giant mango tree obviously planted from a previous habitation. It’s hard to imagine what this valley used to look like before all the non-native plants moved in. The guava has especially taken over, it’s almost a guava forest monoculture. And there is fruit everywhere, it litters the jungle floor, rotten and fermenting, squishing under our feet. Even the stream is full of it and I watch the prawns nibble on it. I’m not really complaining though because I think I end up eating more than 10 guava a day.

Working on the stream is peaceful. It’s fun putting on a wetsuit in the middle of the jungle and sliding through the pools and riffles. If we complete the sites for the day and have some extra time, I’ll snorkel around and look at the gobies and Glauco will spear prawns. The gobies are called ‘o’opu. Most of the species are endemic and some are extreme climbers, known to climb 420ft waterfalls. I watch them suction from rock to rock and hang out in the rapids.

Back at camp, Kelly and I do a little snorkel out towards the channel between Okala Island and the headland. We startle a turtle napping in a naturally carved bowl in the rock. After another filling and delicious dinner, we do dishes in the stream. I enjoy my evening bath at the mouth of the stream, looking up the valley and at the stars and out at the crashing waves.

We are checking off sites as we move farther up the valley each day. I spend the next few days pebbling with Addisen. We do about 3 sites a day. Next to the trail, we see rock walls and terraces from earlier times. At lunchtime, I gnaw on a block of cheese and eat guava. As we hike through the jungle, I’m nervous when going through the muddy pig wallows because of leptospirosis. I’ve gotten it before on the Napali coast on Kauai and it was absolutely awful.

Today, we are going to our farthest site, above the dam that the state put in, about three miles up the valley. It is exciting that at our highest site above the dams, we are still finding hihiwai. It is crazy to think about the journey these snails have been on to get here. The hihiwai are anadramous. Eggs will hatch in the stream, larvae will wash out into the ocean, and after about a year they will begin their journey back up the stream. Truly remarkable. Also, since there are no invasive Tahitian prawns above the dams, we finally see some of the native shrimp. The sad thing is that it feels like we’ve finally left our jungle paradise. The dam and tunnel infrastructure is unsightly and the people working on it have left trash everywhere. The abundance of fish we found below the dams is not here. On our trip back to camp, Noah and Glauco harvest some taro root and leaves to cook up for dinner. We all knew taro had to be cooked to remove the oxalate crystals but we clearly didn’t cook it long enough because we ate some and we all got tingly throats. The irony of us haoles failing to cook taro properly and paying the price is not lost on me.

I had an incredible week working with this crew to survey the beautiful, fragile Waikolu stream. I loved doing fieldwork that included camping and hiking in the jungle. I hope that the data we collected can be used to continue to protect the endemic species that call this place home. Now, a brief stopover on O’ahu and Pearl Harbor before I head to my final internship destination, Channel Islands National Park.

Thanks one last time to Kelly and Glauco for being the most gracious hosts and allowing me to work with them at Kalaupapa for almost a month! I had a wonderful time and learned so much. Thank you SRC and OWUSS for supporting me on my journey.