After arriving in Miami the previous day, in the early hours of Monday morning, Kathryn Grazioso, a marine ecology intern for the South Florida/Caribbean Network (SFCN), picked me up and drove me to the offices of the SFCN inventory and monitoring team. After loading the truck, Mike Feeley, a marine ecologist for SFCN, Kat, and I headed to Key West with the 29-foot boat in tow.

To manage park resources and collection information about ecosystem health over time, the NPS created 32 inventory and monitoring networks. These networks collect and analyze data about the marine and terrestrial ecosystems of over 280 national parks. The data is then used to inform management decisions. The South Florida/Caribbean Network I&M Program encompasses seven parks: Big Cypress National Preserve, Biscayne National Park, Everglades National Park, Virgin Islands National Park, Buck Island Reef National Monument, Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve, and Dry Tortugas National Park (DRTO).

For the next 10 days, I would be assisting SFCN’s marine team as they completed their annual benthic monitoring at DRTO. The MV Fort Jefferson would serve as our transportation to and from the park and our home base. MV Fort Jefferson is a 110-foot, NPS boat used to transport staff and supplies to DRTO. Aboard the Fort Jeff are three crewmembers: Captain Tim, Brian LaVerne, and Mikey Kent, the Park Diving Officer at DRTO.

After unloading our gear onto the MV Fort Jeff and receiving a tour of the quarters, we grabbed dinner in town and appreciated the final few hours of civilization. At 9 am, the following morning, the MV Fort Jeff left Key West and began its 5 hour trip to DRTO (located 70 miles west). DRTO is a 100-square mile national park; however, with only seven small islands, a majority of the park is the ocean. Fort Jefferson, located on Garden Key, the second largest island in DRTO, was designated a National Monument in 1935. The monument was officially expanded and redesignated as Dry Tortugas National Park in 1992. There are only two ways to reach DRTO: boat or seaplane. While a ferry brings tourists to DRTO once a day, today the MV Fort Jefferson held not only the SFCN crew but a DRTO ranger, several DRTO interns, and a few visiting scientists.

View of the MV Fort Jeff as Captain Tim repositioned the boat in the harbor at DRTO

Upon arriving at Fort Jefferson, Captain Tim parked the vessel as everyone on board watched in awe. In the blazing heat, the SFCN group gave Kat, Tom Hyduk, another marine ecology intern, and I a quick tour of the Fort Jefferson. Construction of the Fort Jefferson began in 1847, and although never finished or fully armed, this impressive 19th-century fort was used as a military prison during the Civil War, a coaling station for warships, and a deterrent for passing enemy ships. Today, park staff work to protect the fort and return the impressive structure to its former glory.

In every direction, the views were spectacular. Fort Jefferson’s clean lines complemented the calm waters.

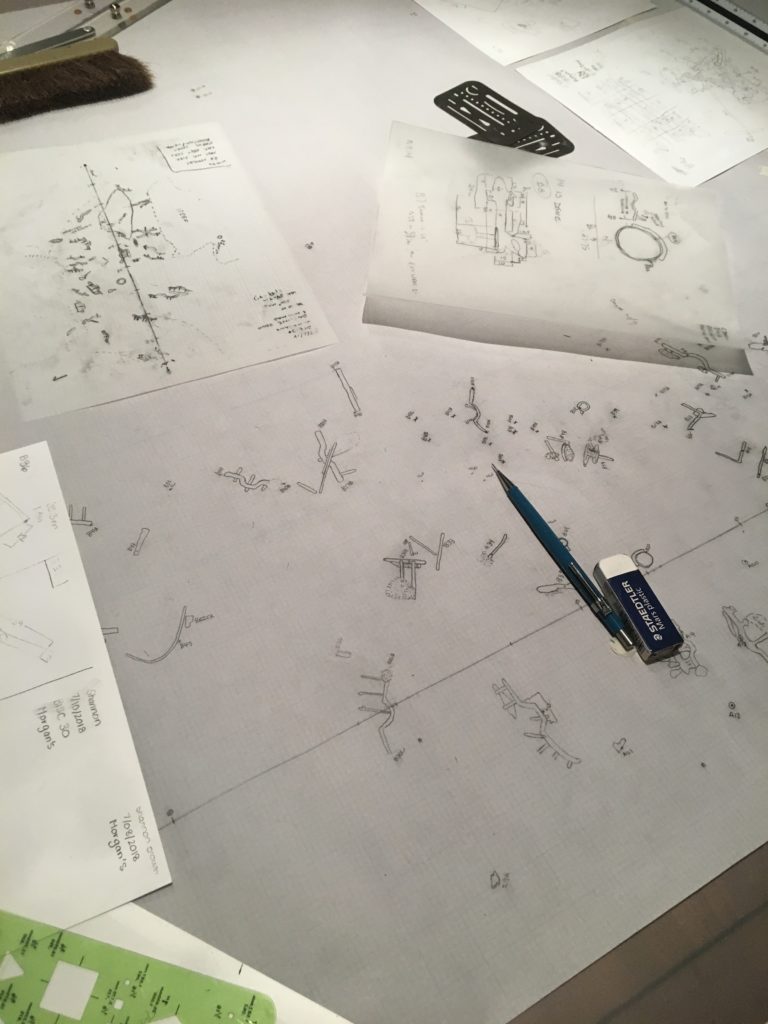

After our tour, we headed back to the MV Fort Jeff and began loading our boat with dive gear for our afternoon practice dive at Bird Key, located south of Fort Jefferson. At the site, before jumping in, Rob Waara, a marine biologist for SFCN, and Lee Richter, a marine biological technician for SFCN, set up a line/buoy for us to moor on. The purpose of this dive was to practice finding metal pins nailed into the substrate and learn how to set up the tapes for the transects. These pins marked both ends of a transect, and a predetermined compass heading was used to find the terminal pin from the start pin. Compass headings and distances also dictated the whereabouts of the subsequent transects. Photographs taken in previous years provided a little context when searching for the pin; however, the coral head or gorgonian located adjacent to the start pin in 2010 may not still be there in 2018.

For most of the collection week, we were fortunate to have crystal calm water.

On Wednesday, we headed back to Bird Key to begin our first day of collection. To mark the location of our first pin, we dropped a buoy attached to a dive weight at a known GPS coordinate. Affectionately known as “Kitty” because of the zip ties tied around the weight resembling whiskers, this buoy drop system allowed us to effectively travel from transect to transect at the surface between dives. On our first dive, Lee, Rob, and Mike set up the tape at the first transect. Rob then took video, while Mike and Lee swam down opposite sides of the transects collecting coral disease or coral species data. Upon demonstrating the data collection process, they signaled Kat, Tom, and I to continue ahead and begin looking for pins. During our two dives that day, Kat, Tom, and I successfully laid a few more transects while quickly discovering the with low visibility finding these metal pins was going to be harder than expected.

Lee travels along one side of the 10 m transect with a 1 m tape and counts the number of coral colonies.

With two dives complete, we puttered back to the MV Fort Jeff with one engine. Unfortunately, during transport, one of the engine’s gas lines was damaged and began leaking gas. That night, we watched Captain Ron, a required viewing if you are visiting DRTO on the MV Fort Jeff.

-

-

Kat rolls up the tape after completing a transect

-

-

Tom ties the tape around the terminal pin

The next day, we returned to Bird Key and followed the same transect/benthic survey procedure. While we spent most of our dives heavily focused on the compass or tape in front of us, as we traversed around, it was hard not to notice the spectacular rugosity at Bird Key. In addition to setting up transects, Tom, Kat, and I were responsible for cleaning the pins (i.e. removing the encrusting organisms). To do so, Kat carried a massive, dull knife to smack the pins clean. While this may sound silly, the knife was extremely effective and also produced a loud noise that often notified the remaining divers of our location.

At Bird Key, this goliath grouper hung out below our boat. It’s the biggest fish I’ve ever seen! PC: Lee Richter

After collecting data from the remaining transects on Friday, we moved onto our next site Santa’s Village, located north of Fort Jefferson. Unlike the previous site, Santa’s Village had larger coral heads which dominated the ocean floor and left little space for seagrass and sand. In addition, pin-organization wise, this site was easier to navigate and required shorter swimming distances between transects, which was good because the site’s depth meant less bottom time. On Saturday, having left Bird Key and the mooring spot officially, we transition to live boating. For the next few days, as we finished up Santa’s Village and continued onto Loggerhead Forest, we would arrive at the site, drop Kitty, then Tom, Kat, and I would head down to set up transects. Sometimes, Rob would accompany us to film each transect. After returning to the boat, Lee and Mike, who had switched from open-circuit to closed-circuit, would descend to collect data. Their rebreathers allowed them to stay down for extended periods of time, which was especially useful since both Santa’s Village and Loggerhead Forest had a lot of disease.

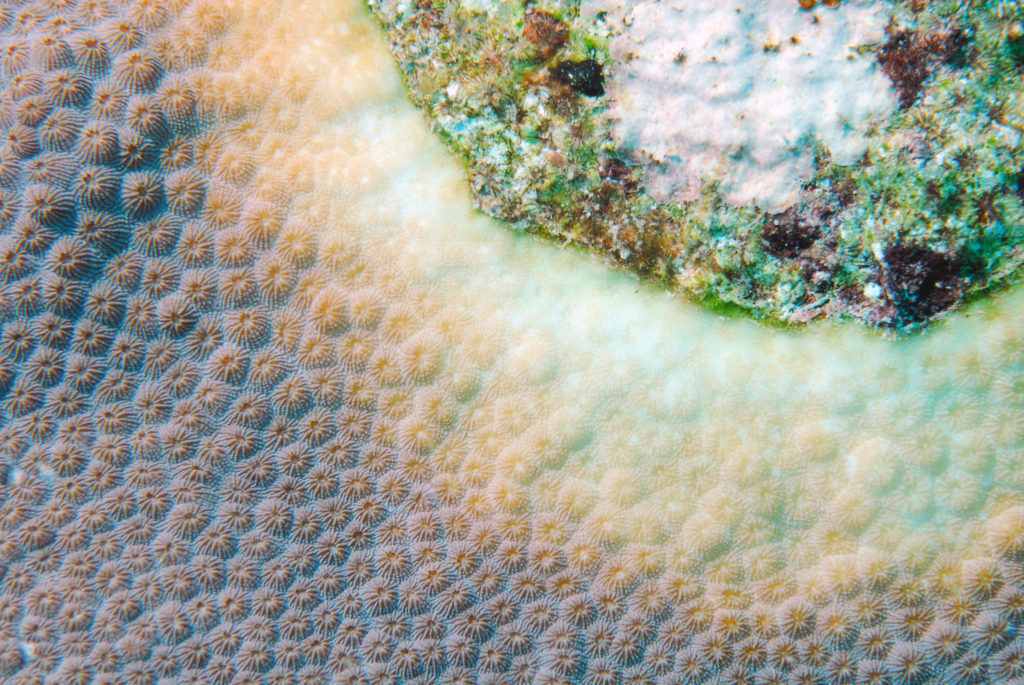

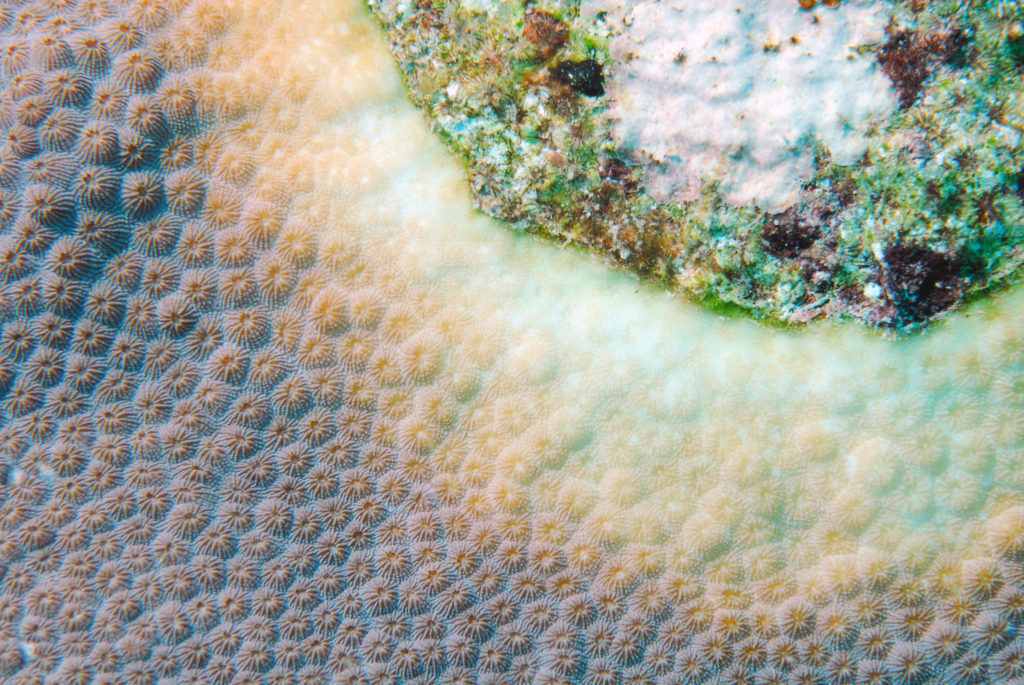

Example of yellow band disease which was commonly observed on Orbicella spp. PC: Rob Waara

One afternoon, after a lovely day of diving, Mikey convinced Tom, Kat, and I to take his tiny sailboat out into the harbor. With limited to no sailboat experience, we all hesitantly agreed. Luckily, Kat had some sailing knowledge and was able to keep us from getting stranded. While we struggled slightly with the sails, we did not capsize, and we returned to shore on our own. So overall, I would consider that a success!

The little sailboat slowly gliding through the water in the distance. PC: Rob Waara

As the days began to meld together, Tom, Kat, and I became very in tune with each other and could have entire conversations underwater solely through hand signals. On the final few transects, we also all practiced data collection. Colony count data would be used to determine disease abundance, whereas species lists helped to understand the diversity at each site. On our final survey dive, we were treated to visitors. Curious dolphins watched as we set up our first transect before disappearing into the abyss.

Kat, Tom, and I chilling at our safety stop. PC: Rob Waara

With all benthic surveys complete, our final 1.5 days would be spent collecting HOBO data from the non-annual sites at DRTO. In total, SFCN has 14 sites around DRTO were benthic surveys are completed. Only three sites are surveyed yearly, while the remaining 11 sites are patch reefs with less relief. Therefore, they are checked every few years on rotation. However, no matter the rotation, the HOBO data (i.e. temperature loggers) needed to be checked every year. To do so, 2-3 divers would descend after Kitty was dropped. Then the team would search for small floats tied to a pin. Upon finding the pin, the floats would be replaced and using a shuttle, the data from the two HOBOs at each site would be transferred underwater for future analysis at the surface. If the HOBO transfer failed, the device was taken to the surface for repair. On our final HOBO dive, Lee, Kat, and I saw a bull shark at our safety stop. Kat and I were just a little excited about seeing our first shark of the trip, especially since it felt like Rob, Lee, and Mike saw one every dive.

After Kat replaced the yellow floats, Tom can be seen collecting the HOBO data with the shuttle.

With HOBO collection complete, we stopped at Loggerhead Key, the largest island in DRTO. The island is home to a lighthouse and a few small houses. Currently, an intern lives on Loggerhead Key and performs turtle walks daily in search of new nests.

Built in 1857, the Loggerhead lighthouse is not currently in use.

As our time at DRTO winded down, we packed up our gear and prepared for the ride home. Our last day at DRTO was July 4th. And while no fireworks are allowed within the park, with a clear sky and amazing lightning storm over the fort, fireworks were definitely not missed as a mix of SFCN, and DRTO employees sat on the bow of the MV Fort Jeff.

On Thursday morning, the boat left the dock and headed back to Key West. When we pulled into the harbor, the SFCN crew worked together to load the vehicles, trailer the boat, and begin the long drive back to Miami. After several bumps in the road, we made it back in the evening. I was fortunate enough to find a home that evening with Kat. The next day, I would once again head to Biscayne National Park. This time, however, I would spend time with the Submerged Resources Center and Southeast Archeological Center as they participated in the Slave Wrecks Project.

Thanks to the fantastic group at SFCN for welcoming me into the family for 10 days. We dove, we laughed, and we ate a lot of cheese balls! Also, thanks to the DRTO group and MV Fort Jeff crew for making my visit to DRTO spectacular!

Quick facts about DRTO:

- 46% of DRTO is a Research Natural Area which was created so the ecosystem could recover with limited human disturbance (i.e. no fishing is allowed)

- Called “Dry” Tortugas because no freshwater can be found on the keys

- Spearfishing and lobstering is not permitted within the park

- More than 200 bird species pass through the area during spring migration

I was able to help trained NOAA volunteers by going out on turtle walks. During the months of June and July, Loggerhead sea turtles come ashore in Islamorada to nest. On our Sea Oats Beach, we had 21 nests and 15 false crawls this season. A false crawl is a marked incident where it looks like a turtle has come ashore to nest but there was no nest dug; this usually happens if the turtle gets spooked or the conditions are unfavourable.

I was able to help trained NOAA volunteers by going out on turtle walks. During the months of June and July, Loggerhead sea turtles come ashore in Islamorada to nest. On our Sea Oats Beach, we had 21 nests and 15 false crawls this season. A false crawl is a marked incident where it looks like a turtle has come ashore to nest but there was no nest dug; this usually happens if the turtle gets spooked or the conditions are unfavourable.

REEF participated in this program by training The Blue Force team to contribute to our database by surveying fish. We also educated them about the lionfish invasion and trained them to properly remove lionfish. It was an amazing opportunity to dive with these men and to learn a little bit about their world. For some of them, this was the first time they had seen a coral reef despite being trained divers for many years.

REEF participated in this program by training The Blue Force team to contribute to our database by surveying fish. We also educated them about the lionfish invasion and trained them to properly remove lionfish. It was an amazing opportunity to dive with these men and to learn a little bit about their world. For some of them, this was the first time they had seen a coral reef despite being trained divers for many years.

from the usual waves of the Gulf of Maine. I was particularly excited for this overnight trip because we would be camping on an island instead of getting a motel room or just driving back to Bigelow. The only downside to a long day of cold water diving is you want a warm shower when you get back, a luxury we were not afforded on an island in the middle of the ocean. However, what this small island lacked in amenities made up for in beauty.

from the usual waves of the Gulf of Maine. I was particularly excited for this overnight trip because we would be camping on an island instead of getting a motel room or just driving back to Bigelow. The only downside to a long day of cold water diving is you want a warm shower when you get back, a luxury we were not afforded on an island in the middle of the ocean. However, what this small island lacked in amenities made up for in beauty.

After 2½ months of living the dream, I have to say goodbye to lovely Durham this week. This summer was definitely not enough time to accomplish everything — I would need about a year to finish the multiple dive safety programs and test them out. That being said, I did accomplish quite a bit in this short time, from “saving” the online seminars to starting a module for DAN First-Aid instructors looking at effective teaching practices. It was a hard-working summer that I wouldn’t change for the world.

After 2½ months of living the dream, I have to say goodbye to lovely Durham this week. This summer was definitely not enough time to accomplish everything — I would need about a year to finish the multiple dive safety programs and test them out. That being said, I did accomplish quite a bit in this short time, from “saving” the online seminars to starting a module for DAN First-Aid instructors looking at effective teaching practices. It was a hard-working summer that I wouldn’t change for the world.